|

Posted on 11/26/2003 12:03:05 AM PST by SAMWolf

|

|

are acknowledged, affirmed and commemorated.

|

| Our Mission: The FReeper Foxhole is dedicated to Veterans of our Nation's military forces and to others who are affected in their relationships with Veterans.

Where the Freeper Foxhole introduces a different veteran each Wednesday. The "ordinary" Soldier, Sailor, Airman or Marine who participated in the events in our Country's history. We hope to present events as seen through their eyes. To give you a glimpse into the life of those who sacrificed for all of us - Our Veterans.

|

|

Clay Tice Jr, then a Major, was in command of the 508th squadron before it arrived in England in April 1944, and he stayed with the squadron until October of that year by which time the squadron was operating on the European mainland from bases in France and Belgium. Tice was a rarity amongst the 404ths pilots in that he was already an experienced combat fighter pilot from the Pacific Theatre with two acredited victories over Japanese Zeros. He had flown both the P38 Lightning and the P51B Mustang, and in the early days at Winkton he had a stated preference for both these aircraft over the P-47 Thunderbolt.  Col. Clay Tice At Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, where the 404th formed up as a fighter bomber group Tice was known for the quality and style of his briefings. Contemporaries at the briefings remember him dressing with some formality, decoration ribbons and all, but they also acknowledged that the quality of his briefings, and the presentation of the material, was superb both in content and style. He believed in the value of tight formation flying, and at Winkton demanded the 507th flew formation so well it stood out in the air from the other squadrons. He was known to fine pilots for flying errors, but it is recorded that he also fined himself when he made similar errors. He could also be innovative, using a loose camera gun from within the cockpit to record the success of dive bombing missions. Whilst in England, Tice flew a silver P47D-22 razorback, Y8*E, known as Elsie.  Clay Tice's P-47, "Elsie". He was the CO of the 507th when it went overseas. This picture was taken in front of the 507th hangar in St. Trond by Bill Lee in 1944. In France Tice was one of the first pilots in the 404th to receive a P47D-25, the new Bubbletop design. After leaving the 404th he went back to the Pacific to his beloved P-38s, commanding the 49th fighter group. Remaining in the Airforce he went on to become Deputy Commander for Test & Operations of the Air Force Flight Test Center, Edwards AFB in 1960. Clay Tice died on July 15. He was 79. Clay was an active participant on CompuServe's AVSIG (aviation) Forum for quite some time before a tragic stroke stole the keyboard from him. Clay's stories of his experiences as both a fighter pilot and test pilot provided both entertainment and history lessons to all who read them. by Col. Clay Tice, Jr., USAF (Ret.) Former World War II fighter ace and USAF test pilot Clay Tice died on July 15. He was 79. Clay was an active participant on CompuServe's AVSIG (aviation) Forum for quite some time before a tragic stroke stole the keyboard from him. Clay's stories of his experiences as both a fighter pilot and test pilot provided both entertainment and history lessons to all who read them. Here is Clay's account of his historic landing in Japan at the end of WW II, starting with the official report he submitted way back then and then continuing with his personal recollections of the event.  The right side of the cowl of Tice's P-47. Bill Lee took this picture in St. Trond, Belgium in 1944. If you are a WWII history buff, you probably know that Gen. MacArthur landed in Japan on 30 August 1945 and accepted the surrender of Japan on 2 September on the battleship Missouri. And according to William Manchester's "American Caesar - Douglas MacArthur 1880-1964" ... "Japan, the only major power whose soil had never been sullied by the boot of an enemy soldier, lost that distinction at dawn on Tuesday, August 28, when Colonel Charles Tench, a member of MacArthur's staff, stepped from a C-47 and set foot on Atsugi's bomb-pocked runway." History is in error on two counts. MacArthur was not the first to take the surrender of Japan nor was Col Tench the first to sully the Japanese soil. The following is a verbatim copy of my report: ARMY AIR FORCES APO 337 26 August 1945 The following is a statement of Lt. Col. CLAY TICE, JR., 0-421355, Commanding Officer, 49th Fighter Group, in regard to the emergency landing on the Japanese homeland on 25 August 1945. I was the leader of Jigger Red flight on 25 August 1945 when two planes of that flight landed on the mainland of Japan. Our mission was a combat sweep around KYUSHU, across the southern tip of HONSHU, thence around SHIKOKU and return to base. The plotted distance of the patrol was 1370 statute miles and flying time was estimated at six hours and forty-five minutes. Instructions were given to hang a 310 gallon external tank in addition to the bomb load, and to fill the tanks to capacity. Pilots were briefed thoroughly on the mission by myself and the length and duration of the mission were stressed. Fuel consumption was estimated at 610 gallons allowing a one hour reserve. Total gas carried was approximately 700 gallons.  49th Fighter Group The flight, composed of eight P-38s of the 7th Fighter Squadron, plus one spare, was airborne from MOTUBA Strip at 0805. Cruise on course and during sweep was 1800 rpm and 30"Hg in auto lean as briefed, with an indicated air speed of 180 mph. Prior to making landfall on KYUSHU, two aircraft aborted and returned to base due to mechanical difficulty. I made landfall at MAKURAZAKI at 0950. A course was then set for NAGASAKI with slight deviations to check shipping, arriving over NAGASAKI at 1025. I proceeded to ISAHAY to OMUTA thence to YANAGAWA to KURUME to NAKATSU. Time over NAKATSU was 1100. My course was then over NAGASU to TOMIKUDURA to YA SHIMA Island to NAGAHAMA at 1122. Approximate air mileage to this point was 600 miles. Flight Officer HALL, number two (2) in the second flight, called for a reduction in rpm because he was low on gas. His radio transmission was very poor and all messages from him were relayed through his flight commander, Captain KOPECKY. I asked Flight Officer HALL how many gallons of gas he had left and answer was approximately 240 gallons. At that time we were 540 miles from base and I reduced power settings to 1600 rpm and 28"Hg. Low visibility forced me around the peninsula to SHONE and down to SAEKI. I then called Flight Officer HALL again on his gas supply and understood him to say that he had about 140 gallons. I decided that his rate of fuel consumption and gas supply would not permit his return to a friendly base and turned out to sea off FURUE to jettison bombs at 1143. No flak had been encountered over Japanese installations and I believed that a landing at a suitable Japanese airdrome would be preferable to the certain loss of a plane and the possible loss of a pilot in the event a forced ditching at sea was made. I called Jukebox 36 (B-17 of the 6th Air Sea Rescue Squadron) and informed him of my intentions and requested assistance. I landed at NITTAGAHARA, 450 miles from base, at 1205. There were no Japanese in sight after landing and I checked the gas supply in flight Officer HALL's plane. He had dropped his external tank previous to informing me of his difficulty and upon inspection, I found that his wing tanks were dry and I estimated his fuel at 150 gallons in mains and reserves by visual check of fuel indicators and tanks.  At 1305 we were contacted by officers and men of the Japanese Army and although conversation was difficult, we were greeted in a friendly manner. Jukebox 36 landed at approximately 1315 and with a fuel pump and hose furnished by the Japanese, we transferred approximately 260 gallons of gas from the B-17 to the P-38. After landing at NITTAGAHARA, I dropped my external tank on the runway still containing 25 to 50 gallons. I had used but 15 minutes of my internal gas supply by that time. Flight Officer HALL and I were airborne behind the B-17 at 1445 and set course for base where we landed at 1645 after cruising at 1800 rpm and 28"Hf. I had approximately 240 gallons of gas left after landing. All cruise settings were in auto lean. Flight Officer HALL had approximately 210 gallons remaining. As far as it is possible to ascertain from interrogation of line personnel concerned, Flight Officer HALL's plane was serviced with 300 gallons in the external tank and all internal tanks topped off. From preliminary investigation, it is believed that the cross feed valve was defective thus permitting siphoning of the fuel supply. I carried out my landing on Japanese territory in the belief that Flight Officer HALL could not safely return to the nearest Allied base and that under the circumstances it would be the safest course of action if I landed prior to Flight Officer HALL because I thought that in the case of difficulty with Japanese, my rank and experience would be of benefit. Flight Officer HALL's lack of combat experience and the nervousness that he showed after landing and when confronted by the Japanese confirmed my belief.  Instructions in all details of the fuel system and gas consumption characteristics of the P-38 are now being given and will be followed by actual demonstrations and written examinations by all pilots of this organization. All efforts will be made to prevent any possible reoccurrence of this situation either by pilot error or mechanical failure. CLAY TICE, JR. Lt. Colonel, Air Corps If confirming references are required: "General Kenney Reports" by Geoge C. Kenney Duell, Sloan And Pearce, New York Pgs 573 & 574 "Flying Buccaneers - The Illustrated Story of Kenney's Fifth Air Force" by Steve Birdsall Doubleday & Company, Inc., Garden City, New York Pgs 289 & 290 Note: I still have one of the officer's sword in my hall closet. This is the official record -- all of the details are missing.

|

Flight Officer Hall was a newly assigned pilot and this was his 1st mission so my pre-mission briefing was most comprehensive. We were flying fairly new P-38L5s with leading edge 'Tokyo' tanks. The fuel system setup with these leading edge tanks required that the tops of each set of tanks be knocked off right after takeoff to prevent siphoning of fuel overboard. The squadron was briefed in the standard procedure of taking off on mains, switching to leading edges for about 5 minutes, then to reserves for 5 minutes and then to switch both engines to the one 300 gallon drop tank on the left pylon. A 1,000# GP was hung on the right pylon and our mission was surveillance of the eastern half of Kyushu and then up at far as Hiroshima before returning to base. Our orders: To strike any movement of Japanese military forces land or sea. Our flight plan was detailed in official flight report previously rendered.

After making landfall, the first thing of interest was Nagasaki which had been the most recent recipient of a nuke. The city was divided by a ridge running east/west and the bomb had fallen on the northern half. The ridge apparently had been high enough to shield the southern portion of the city from the blast as things were fairly normal there, with cars and streetcars on the streets. The northern half was still burning in some sections with rest of that part of the city just a blackened rubble.

The only way to guarantee a reasonably safe bailout in a 38 was to roll inverted, trim nose up and drop out. But there was another problem with bailing out. Given that he would be in good enough shape to get into his rubber raft and the RB-17 dropped the boat to him, could the boat be dropped exactly upwind of his raft and could he get to it in time? There had been reports of boats being dropped but being blown away before the pilot could get to it. Seems that the higher freeboard of the rescue boat acted like a sail while the pilot in his raft sat there and paddled like mad to catch it to no avail.

As we were on course back to Oki, I pondered the choices. The thought of being first to land in Japan never entered my mind at that time as saving Hall was uppermost in my thoughts. Landing on a small Japanese strip seemed the best way to save him. Checking my maps I found that there was a little airfield on the east coast of Kyushu at Nittagahara and decided to land there if it appeared safe to do so and it was big enough for the 38. After landing I planned on taking Hall aboard on my lap and flying him back to Oki.

After two or three more low passes, I landed on the short [2,500] asphalt strip laid out on a grass field and taxied to the west end of the runway which had a circular turn-around pad. Positioning my 38 facing the length of runway and keeping the fans turning for a rapid departure if necessary, I called Hall in and had him taxi up and park beside me and keep his fans turning also. After a few minutes there was no sign of activity so we shut down and got out of the birds.

I asked Hall about his fuel handling procedures and when had he dropped his 300 gallon tank. He told me that he dropped it just before we made landfall because the fuel pressure on both engines dropped and when the engines started to sputter he switched to mains and dropped the 'empty tank.' When asked about the procedure he used to drop the tank he replied that he had just pulled the tank release handle while cruising in formation as tail-end charlie.

Hall was very nervous as I asked him to stay with the 38s while I checked a couple of Tonys to see if I could get one started. I thought that it would clank up the troops back on Oki if landed there in a Jap Tony while Hall flew my 38 back. My good idea came to naught when I found that there was a starter lug on a shaft protruding from the prop nose cone -- they were started by having a truck equipped with a motor and crank shaft backing up to the a/c and engaging this lug to turn the engine over. Must have had a long drive shaft or it would been somewhat of a thrill for the mechs on the truck!

www.web-birds.com

home.att.net/~historyzone

www.flyingknights.net

www.brooksart.com

p-38online.com

"The Fork-Tailed Devil" The Lockheed P-38 Lightning was simply the most versatile aircraft used in World War II. After a lengthy developmental period, the P-38 eventually flourished in multiple roles. In its designed role, the P-38 was an effective fighter and was the main aircraft for most of the aces in the Pacific Theater of Operations. However, the P-38 was modified to become a world-class reconnaissance aircraft, an effective night fighter, and even an excellent strike/attack aircraft. Many bomber crewmembers would see its distinctive profile approaching and feel a little safer. Many enemy fighters and bombers would tremble with fear with the approach of the Fork-Tailed Devil! 'It was a marveleous aircraft! It was the best aircraft I flew in the war by far. I never flew the P-51, its been one of my life regrets, but I flew just about everything else there was. I liked the P-38s rate of climb, its speed, the way it handled, and its firepower directly out the nose. The P-38 would turn with almost anything, in fact it would out turn the P-47, out climb it, and out maneuver it. The P-38 was one of the great aircraft of WWII.' -- Charles MacDonald, P-38 Ace 'On my first confrontation with the P-38, I was astonished to find an American aircraft that could outrun, outclimb, and outdive our Zero which we thought was the most superior fighter plane in the world. The Lightning's great speed, its sensational high altitude performance, and especially its ability to dive and climb much faster than the Zero presented insuperable problems for our fliers. The P-38 pilots, flying at great height, chose when and where they wanted to fight with disastrous results for our own men. The P-38 boded ill for the future and destroyed the morale of the Zero fighter Pilot.' -- Saburo Sakai, Japanese Ace |

Folks, be sure to update your anti-virsu software and get the very latest critical updates for your computer.

Today's classic warship, USS Arkansaw (BB-33)

Wyoming class battleship

displacement. 27,243 tons

length. 562'

beam. 93'1

draft. 28'6"

speed. 21.05 k.

complement. 1,036

armament. 12x12", 21x5", 2x21" tt.

The USS Arkansas (Battleship No. 33) was laid down on 25 January 1910 at Camden, N.J., by the New York Shipbuilding Co.; launched on 14 January 1911; sponsored by Miss Nancy Louise Macon; and commissioned at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on 17 September 1912, Capt. Roy C. Smith in command.

The new battleship took part in a fleet review by President William H. Taft in the Hudson River off New York City on 14 October, and received a visit from the Chief Executive that day. She then transported President Taft to the Panama Canal Zone for an inspection of the unfinished isthmian waterway. After putting the inspection party ashore, Arkansas sailed to Cuban waters for shakedown training. She then returned to the Canal Zone on 26 December to carry President Taft to Key West, Fla.

Following this assignment, Arkansas joined the Atlantic Fleet for maneuvers along the east coast. The battleship began her first overseas cruise in late October 1913, and visited several ports in the Mediterranean. At Naples, Italy, on 11 November 1913, the ship celebrated the birthday of the King of Italy.

Earlier in October 1913, a coup in Mexico had brought to power a dictator, Victoriano Huerta. The way in which Huerta had come to power, however, proved contrary to the idealism of President Woodrow Wilson, who insisted on a representative government, rather than a dictatorial one, south of the American-Mexican border. Mexico had been in turmoil for several years, and the United States Navy maintained a force of ships in those waters ready to protect American lives.

In a situation where tension exists between two powers, incidents are bound to occur. One such occurred at Tampico in the spring of 1914, and although the misunderstanding was quickly cleared up locally, the prevailing state of tension produced an explosive situation. Learning that a shipment of arms for Huerta was due to arrive at Veracruz, President Wilson ordered the Navy to prevent the landing of the guns by seizing the customs house at that port.

While a naval force under Rear Admiral Henry T. Mayo was already present in Mexican waters, the President directed that the Atlantic Fleet, under Rear Admiral Charles J. Badger, proceed to Veracruz. Arkansas participated in the landings at Veracruz, contributing a battalion of four companies of bluejackets, a total of 17 officers and 313 enlisted men under the command of Lt. Comdr. Arthur B. Keating. Among the junior officers was Lt. (jg.) Jonas H. Ingram, who would be awarded the Medal of Honor for heroism at Veracruz, as would Lt. John Grady, who commanded the artillery of the 2d Seaman Regiment.

Landing on 22 April, Arkansas's men took part in the slow, methodical street fighting that eventually secured the city. Two Arkansas sailors, Ordinary Seamen Louis O. Fried and William L. Watson, died of their wounds on 22 April. Arkansas's battalion returned to the ship on 30 April, and the ship remained in Mexican waters through the summer before setting course on 30 September to return to the east coast. During her stay at Veracruz, she received calls from Capt. Franz von Papen, the German military attaché to the United States and Mexico, and Rear Admiral Christopher Cradock, on 10 and 30 May 1914, respectively.

The battleship reached Hampton Roads, Va., on 7 October, and after a week of exercises, Arkansas sailed to the New York Navy Yard, for repairs and alterations. She then returned to the Virginia Capes area for maneuvers on the Southern Drill Grou nds. On 12 December, Arkansas returned to the New York Navy Yard for further repairs.

She was underway again on 16 January 1915, and returned to the Southern Drill Grounds for exercises there from 19 to 21 January. Upon completion of these, Arkansas sailed to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, for fleet exercises. Returning to Hampton Roads on 7 April, the battleship began another training period in the Southern Drill Grounds. On 23 April, she headed to the New York Navy Yard for a two-month repair period. Arkansas then left New York on 25 June bound for Newport, R.I. She conducted torpedo practice and tactical maneuvers in Narragansett Bay through late August.

Returning to Hampton Roads on 27 August, the battleship engaged in maneuvers in the Norfolk area through 4 October, then sailed once again to Newport. There, Arkansas carried out strategic exercises from 5 to 14 October. On 15 October, the battleship arrived at the New York Navy Yard for drydocking. Underway on 8 November, she returned to Hampton Roads. After a period of routine operations, Arkansas went back to Brooklyn for repairs on 19 October. The ship sailed on 5 January 1916 for Hampton Roads. Pausing there only briefly, Arkansas pushed on to the Caribbean for winter maneuvers.

She visited the West Indies and Guantanamo Bay before returning to the United States on 12 March for torpedo practice off Mobile Bay. The battleship then steamed back to Guantanamo Bay on 20 March and remained there until mid-April. On 15 April, the battleship was once again at the New York Navy Yard for overhaul.

On 6 April 1917, the United States entered World War I on the side of the Allied and Associated Powers. The declaration of war found Arkansas attached to Battleship Division 7 and patrolling the York River in Virginia. For the next 14 months, Arkansas carried out patrol duty along the east coast and trained gun crews for duty on armed merchantmen.

In July 1918, Arkansas received orders to proceed to Rosyth, Scotland to relieve Delaware (Battleship No. 28). Arkansas sailed on 14 July. On the eve of her arrival in Scotland, the battleship opened fire on what was believed to be the periscope wake of a German U-boat. Her escorting destroyers dropped depth charges, but scared no hits. Arkansas then proceeded without incident and dropped anchor at Rosyth on 28 July.

Throughout the remaining three and one-half months of war, Arkansas and the other American battleships in Rosyth operated as part of the British Grand Fleet as the 6th Battle Squadron.

The armistice ending World War I became effective on 11 November. The 6th Battle Squadron and other Royal Navy units sailed to a point some 40 miles east of May Island at the entrance of the Firth of Forth. Arkansas was present at the internment of the German High Seas Fleet in the Firth of Forth on 21 November 1918.

The American battleships were detached from the British Grand Fleet on 1 December. From the Firth of Forth, Arkansas sailed to Portland, England, thence out to sea to meet the transport GEORGE Washington, with President Wilson on board. Arkansas-along with other American battleships-escorted the President's ship into Brest, France, on 13 December 1918. From that French port, Arkansas sailed to New York City, where she arrived on 26 December to a tumultuous welcome. Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels reviewed the assembled battleship fleet from the yacht Mayflower.

Following an overhaul the Norfolk Navy Yard, Arkansas joined the fleet in Cuban waters for winter maneuvers. Soon thereafter, the battleship got underway to cross the Atlantic. On 12 May 1919, she reached Plymouth, England; thence she headed back out in the Atlantic to take weather observations on 19 May and act as a reference vessel for the flight of the Navy Curtiss (NC) flying boats from Trepassey Bay, Newfoundland, to Europe.

Her role in that venture competed, Arkansas proceeded thence to Brest, where she embarked Admiral William S. Benson, the Chief of Naval Operations, and his wife, on 10 June, upon the admiral's return from the Peace Conference in Paris, before departing for New York. She arrived on 20 June 1919.

Arkansas sailed from Hampton Roads on 19 July 1919, assigned to the Pacific Fleet. Proceeding via the Panama Canal, the battleship steamed to San Francisco, where, on 6 September 1919, she embarked Secretary of the Navy and Mrs. Josephus Daniels. Disembarking the Secretary and his wife at Blakely Harbor, Wash., on the 12th, Arkansas was reviewed by President Wilson on the 13th, the Chief Executive having embarked in the famed Oregon (Battleship No. 3). On 19 September 1919, Arkansas entered the Puget Sound Navy Yard for a general overhaul. Resuming her operations with the fleet in May 1920, Arkansas operated off the California coast. On 17 July 1920, Arkansas received the designation BB-33 as the ships of the fleet received alphanumeric designations. That September, she cruised to Hawaii for the first time. Early in 1921, the battleship visited Valparaiso, Chile, manning the rail in honor of the Chilean president.

Arkansas's peacetime routine consisted of an annual cycle of training interspersed with periods of upkeep or overhaul. The battleship's schedule also included competitions in gunnery and engineering and an annual fleet problem. Becoming flagship for the Commander, Battleship Force, Atlantic Fleet, in the summer of 1921, Arkansas began operations off the east coast that August.

For a number of years, Arkansas was detailed to take midshipmen from the Naval Academy on their summer cruises. In 1923, the battleship steamed to Europe, visiting Copenhagen, Denmark (where she was visited by the King of Denmark on 2 July 1923); Lisbon, Portugal; and Gibraltar. Arkansas conducted another midshipman training cruise to European waters the following year, 1924. In 1925, the cruise was to the west coast of the United States. During this time, on 30 June 1925, Arkansas arrived at Santa Barbara, Calif. in the wake of an earthquake. The battleship, along with Mccawley (DD-276) and Eagle 34 (PE- 34) landed a patrol of bluejackets for policing Santa Barbara, and established a temporary radio station ashore for the transmission of messages.

Upon completion of the 1925 midshipman cruise, Arkansas entered the Philadelphia Navy Yard for modernization. Her coal-burning boilers were replaced with oil-fired ones. Additional deck armor was installed, a single stack was substituted for the original pair, and the after cage mast was replaced by a low tripod. Arkansas left the yard in November 1926 and, after a shake-down cruise along the eastern seaboard and to Cuban waters, returned to Philadelphia to run acceptance trials. Resuming her duty with the fleet soon thereafter, she operated from Maine to the Caribbean; on 5 September 1927, she was present at ceremonies unveiling a memorial tablet honoring the French soldiers and sailors who died during the campaign at Yorktown in 1781.

In May 1928, Arkansas again embarked midshipmen for their practice cruise along the eastern seaboard and down into Cuban waters. During the first part of 1929, she operated near the Canal Zone and in the Caribbean, returning in May 1929 to the New York Navy Yard for overhaul. After embarking midshipmen at Annapolis, Arkansas carried out her 1929 practice cruise to Mediterranean and English waters, returning in August to operate with the Scouting Fleet off the east coast.

In 1930 and 1931, Arkansas was again detailed to carry out midshipmen's practice cruises; in the former year she visited Cherbourg, France; Kiel, Germany; Oslo, Norway; and Edinburgh, Scotland; in the latter her itinerary included Copenhagen, Denmark; Greenock, Scotland; and Cadiz, Spain, as well as Gibraltar. In September 1991, the ship visited Halifax, Nova Scotia. In October Arkansas participated in the Yorktown Sesquicentennial celebrations, embarking President Herbert Hoover and his party on 17 October and taking them to the exposition. She later transported the Chief Executive and his party back to Annapolis on 19 and 20 October. Upon her return, the battleship entered the Philadelphia Navy Yard, where she remained until January 1932.

Upon leaving the navy yard, Arkansas sailed for the west coast, calling at New Orleans, La., en route, to participate in the Mardi Gras celebration. Assigned duty as flagship of the Training Squadron, Atlantic Fleet, Arkansas operated continuously on the west coast of the United States into the spring of 1994, at which time she returned to the east coast.

In the summer of 1934, the battleship conducted a midshipman practice cruise to Plymouth, England; Nice, France; Naples, Italy, and to Gibraltar, returning to Annapolis in August; proceeding thence to Newport, R. I., where she manned the rail for President Franklin D Roosevelt as he passed on board the yacht Nourmalhal, and was present for the International Yacht Race. Arkansas' cutter defeated the cutter from the British light cruiser HMS Dragon for the Battenberg Cup, and the City of Newport Cup.

In January 1935, Arkansas transported the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, to Culebra for a fleet landing exercise, and in June conducted a midshipman practice cruise to Europe, visiting Edinburgh, Oslo (where King Haakon VII of Norway visited the ship), Copenhagen, Gibraltar and Funchal on the island of Madeira. After disembarking Naval Academy midshipmen at Annapolis in August 1935, Arkansas proceeded to New York. There she embarked reservists from the New York area and conducted a Naval Reserve cruise to Halifax, Nova Scotia in September. Upon completion of that duty, she under went repairs and alterations at the New York Navy Yard that October.

In January 1936, Arkansas participated in Fleet Landing Exercise No. 2 at Culebra, and then visited New Orleans for the Mardi Gras festivities before she returned to Norfolk for a navy yard overhaul which lasted through the spring of 1996. That summer she carried out a midshipman training cruise to Portsmouth, England; Goteborg, Sweden; and Cherbourg, before she returned to Annapolis that August. Steaming thence to Boston, the battleship conducted a Naval Reserve training cruise before putting into the Norfolk Navy Yard for an overhaul that October.

The following year, 19937, saw Arkansas make a midshipman practice cruise to European waters, visiting ports in Germany and England, before she returned to the east coast of the United States for local operations out of Norfolk. During the latter part of the year, the ship also ranged from Philadelphia and Boston to St., Thomas, Virgin Islands, and Cuban waters. During 1938 and 1939, the pattern of operations largely remained as it had been in previous years, her duties in the Training Squadron largely confining her to the waters of the eastern seaboard.

The outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939 found Arkansas at Hampton Roads, preparing for a Naval Reserve cruise. She soon got underway and transported seaplane mooring and aviation equipment from the naval air station at Norfolk to Narragansett Bay for the seaplane base that was to be established there. While at Newport, Arkansas took on board ordnance material for destroyers and brought it back to Hampton Roads.

Arkansas departed Norfolk on 11 January 1940, in company with Texas (BB-35) and New York (BB-34), and proceeded thence to Guantanamo Bay for fleet exercises. She then participated in landing exercises at Culebra that February, retu rning via St. Thomas and Culebra to Norfolk. Following an overhaul at the Norfolk Navy Yard (18 March to 24 May), Arkansas shifted to the Naval Operating Base (NOB), Norfolk, where she remained until 30 May. Sailing on that day for Annapolis, the battleship, along with Texas and New York, conducted a midshipman training cruise to Panama and Venezuela that summer. Before the year was out, Arkansas would conduct three V-7 Naval Reserve training cruises, these voyages taking her to Guantanamo Bay, the Canal Zone, and Chesapeake Bay.

Over the months that followed, the United States gradually edged toward war in the Atlantic; early the following summer, after the decision to occupy Iceland bad been reached, Arkansas accompanied the initial contingent of marines to that place. That battleship, along with New York, and the light cruiser Brooklyn (CL-40) provided the heavy escort for the convoy. Following this assignment, Arkansas sailed to Casco Bay Maine, and was present there when the Atlantic Charter conferences took place on board Augusta (CA-31) between President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. During the conference, the battleship provided accommodations for the Under Secretary of State, Sumner Welles, and Mr. Averell Harriman from 8 to 14 August 1941.

The outbreak of war with the Japanese attack upon the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor found Arkansas at anchor in Casco Bay, Maine. One week later, on 14 December, she sailed to Hvalfjordur, Iceland. Returning to Boston, via Argentia, on 24 January 1942, Arkansas spent the month of February carrying out exercises in Casco Bay in preparation for her role as an escort for troop and cargo transports. On 6 March, she arrived at Norfolk to begin overhaul. Underway on 2 July, Arkansas conducted shakedown in Chesapeake Bay, then proceeded to New York City, where she arrived on 27 July.

The battleship sailed from New York on 6 August, bound for Greenock, Scotland. Two days later, the ships paused at Halifax, Nova Scotia, then continued on through the stormy North Atlantic. The convoy reached Greenock on the 17th, and Arkansas returned to New York on 4 September. She escorted another Greenock-bound convoy across the Atlantic, then arrived back at New York on 20 October. With the Allied invasion of North Africa, American convoys were routed to Casablanca to support the operations. Departing New York on 3 November, Arkansas covered a troop convoy to Morocco, and returned to New York on 11 December for overhaul.

On 2 January 1943, Arkansas sailed to Chesapeake Bay for gunnery drills. She returned to New York on 30 January and began loading supplies for yet another transatlantic trip. The battleship made two runs between Casablanca and New York City from February through April. In early May, Arkansas was dry-docked at the New York Navy Yard, emerging from that period of yard work to proceed to Norfolk on 26 May.

Arkansas assumed her new duty as a training ship for midshipmen, based at Norfolk. After four months of operations in Chesapeake Bay, the battleship returned to New York to resume her role as a convoy escort. On 8 October, the ship sailed for Bangor, Ireland. She was in that port throughout November, and got underway to return to New York on 1 December. Arkansas then began a period of repairs on 12 December. Clearing New York for Norfolk two days after Christmas of 1943, Arkansas closed the year in that port.

The battleship sailed on 19 January 1944 with a convoy bound for Ireland. After seeing the convoy safely to its destination, the ship reversed her course across the Atlantic and reached New York on 13 February. Arkansas went to Casco Bay on 28 March for gunnery exercises, before she proceeded to Boston on 11 April for repairs.

On 18 April, Arkansas sailed once more for Bangor, Ireland. Upon her arrival, the battleship began a training period to prepare for her new role as a shore bombardment ship. On 3 June, Arkansas sailed for the French coast to support the Allied invasion of Normandy. The ship entered the Baie de la Seine on 6 June, and took up a position 4,000 yards off "Omaha" beach. At 0552, Arkansas's guns opened fire. During the day, the venerable battleship underwent shore battery fire and air attacks; over ensuing days she continued her fire support. On the 13th, Arkansas shifted to a position off Grandcamples Bains.

On 25 June 1944, Arkansas dueled with German shore batteries off Cherbourg, the enemy repeatedly straddling the battleship but never hitting her. Her big guns helped support the Allied attack on that key port, and led to the capture of it the following day. Retiring to Weymouth, England, and arriving there at 2220, the battleship shifted to Bangor, on 30 June.

Arkansas stood out to sea on 4 July, bound for the Mediterranean. She passed through the Strait of Gibraltar and anchored at Oran, Algeria, on 10 July. On the 18th, she got underway, and reached Taranto, Italy, on 21 July. The battleship remained there until 6 August, then shifted to Palermo, Sicily, on the 7th.

On 14 August, Operation "Anvil" the invasion of the southern French coast between Toulon and Cannes, began. Arkansas provided fire support for the initial landings on 15 August, and continued her bombardment through 17 August. After stops at Pa lermo and Oran, Arkansas set course for the United States. On 14 September, she reached Boston, and received repairs and alterations through early November. The yard period completed on 7 November, Arkansas sailed to Casco Bay for three days of refresher training. On 10 November, Arkansas shaped a course south for the Panama Canal Zone. After transiting the canal on 22 November, Arkansas headed for San Pedro, Calif. On 29 November, the ship was again underway for exercis es held off San Diego. She returned on 10 December to San Pedro.

After three more weeks of preparations, Arkansas sailed for Pearl Harbor on 20 January 1945. One day after her arrival there, she sailed for Ulithi, the major fleet staging area in the Carolines, and continued thence to Tinian, where she arrived on 12 February. For two days, the vessel held shore bombardment practice prior to her participation in the assault on Iwo Jima.

At 0600 on 16 February, Arkansas opened fire on Japanese strong points on Iwo Jima as she lay off the island's west coast. The old battlewagon bombarded the island through the 19th, and remained in the fire support area to provide cover during t he evening hours. During her time off the embattled island, Arkansas shelled numerous Japanese positions, in support of the bitter struggle by the marines to root out and destroy the stubborn enemy resistance. She cleared the waters off Iwo Ji ma on 7 March to return to Ulithi. After arriving at that atoll on the 10th, the battleship rearmed, provisioned, and fueled in preparation for her next operation, the invasion of Okinawa.

Getting underway on 21 March, Arkansas began her preliminary shelling of Japanese positions on Okinawa on 25 March, some days ahead of the assault troops which began wading ashore on 1 April. The Japanese soon began an aerial onslaught, and Arkansas fended off several kamikazes. For 46 days, Arkansas delivered fire support for the invasion of Okinawa. On 14 May, the ship arrived at Apra Harbor, Guam, to await further assignment.

After a month at Apra Harbor, part of which she spent in drydock, Arkansas got underway on 12 June for Leyte Gulf. She anchored there on the 16th, and remained in Philippine waters until the war drew to a close in August. On the 20th of that month, Arkansas left Leyte to return to Okinawa, and reached Buckner Bay on 23 August. After a month spent in port, Arkansas embarked approximately 800 troops for transport to the United States as part of the "Magic Carpet" to return American servicemen home as quickly as possible. Sailing on 23 September, Arkansas paused briefly at Pearl Harbor en route, and ultimately reached Seattle on 15 October. During the remainder of the year, the battleship made three more trips to Pear l Harbor to shuttle soldiers back to the United States.

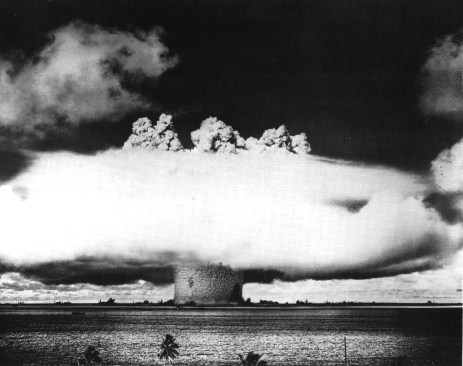

During the first months of 1946, Arkansas lay at San Francisco. In late April the ship got underway for Hawaii. She reached Pearl Harbor on 8 May, and stood out of Pearl Harbor on 20 May, bound for Bikini Atoll, earmarked for use as target for atomic bomb testing in Operation "Crossroads." On 25 July 1946, the venerable battleship was sunk in Test "Baker" at Bikini. Decommissioned on 29 July 1946, Arkansas was struck from the Naval Vessel Register on 15 August 1946.

The black spot on the column of the mushroom is believed to be debris from the USS Arkansas

Arkansas received four battle stars for her World War II service.

Have some more, it's stronger than the other but no as strong as Darksheares....

Have some more, it's stronger than the other but no as strong as Darksheares....

Look ma, no hands!

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.