"The Good Shepherd": The Readings for the Fourth Sunday after Easter

|

|

|

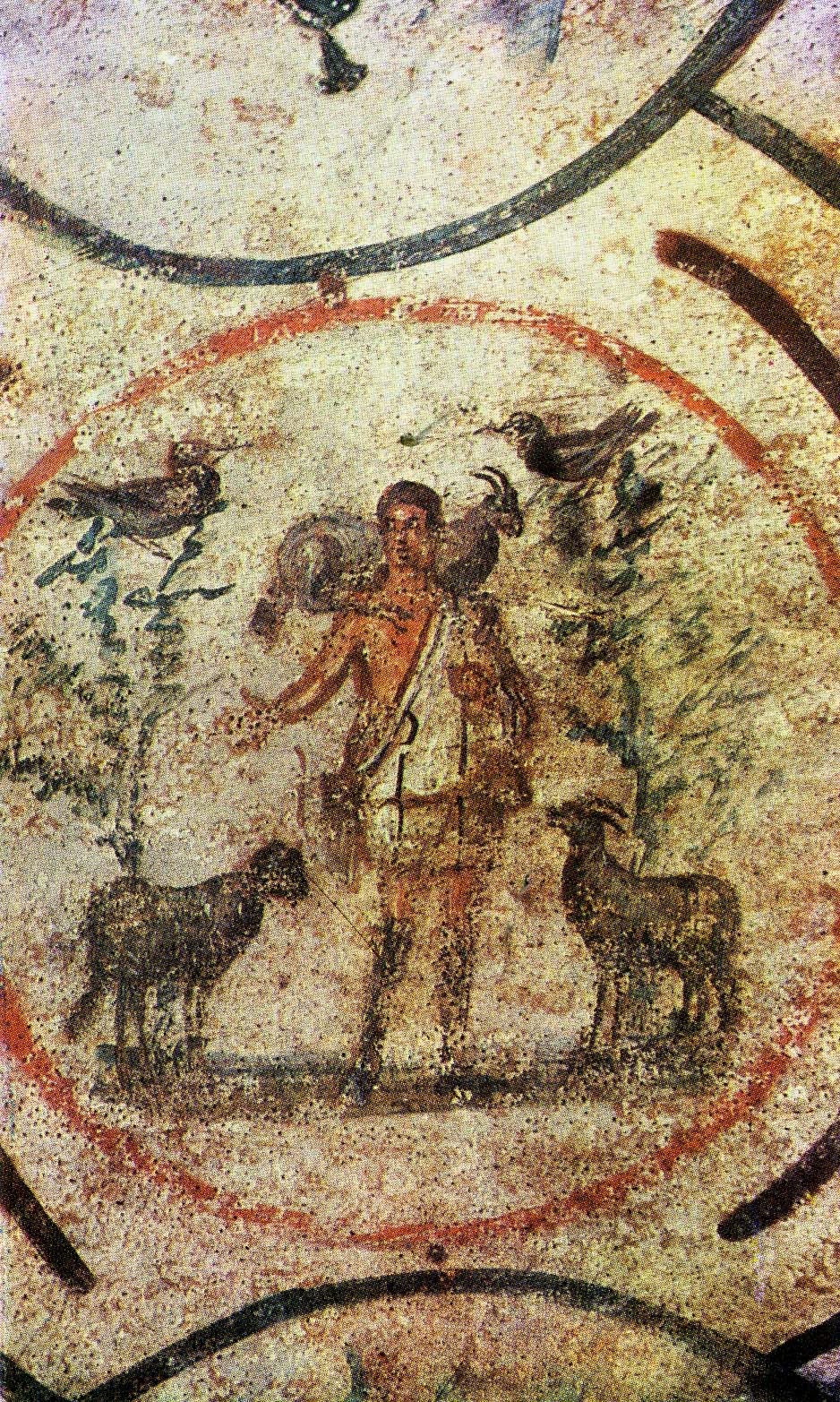

Image of Christ the Good Shepherd

from Catacombs of St. Pricilla in Rome

ca. 3rd cent. |

This Sunday the lectionary turns our attention to John 10, where Christ describes himself as both the "door" of the sheepfold and (perhaps more famously) as the good shepherd.

These two images are key to understanding the selection of the first and second readings, which focus on (1) Peter's speech, highlighting the way salvation is found in Christ and (2) a reading from 1 Peter which climaxes in a description of Christ's role as the Good Shepherd.

Let us look at these readings more carefully. . .

FIRST READING: Acts 2:14a, 36-41

Then Peter stood up with the Eleven,

raised his voice, and proclaimed:

“Let the whole house of Israel know for certain

that God has made both Lord and Christ,

this Jesus whom you crucified.”

Now when they heard this, they were cut to the heart,

and they asked Peter and the other apostles,

“What are we to do, my brothers?”

Peter said to them,

“Repent and be baptized, every one of you,

in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins;

and you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit.

For the promise is made to you and to your children

and to all those far off,

whomever the Lord our God will call.”

He testified with many other arguments, and was exhorting them,

“Save yourselves from this corrupt generation.”

Those who accepted his message were baptized,

and about three thousand persons were added that day.

The context of the first reading in the book of Acts is Pentecost. Peter is here giving the inaugural sermon of the ministry of the post-Easter apostolic mission. Here are a few things worth noting about this reading.

1. Peter addresses "the whole house of Israel". This is significant as it indicates that the mission of the twelve is to announce the good news to all the tribes of Israel. Of course, Israel had originally consisted of twelve tribes.

The language of "the whole house of Israel" seems to evoke hopes for the restoration of all twelve tribes. The terminology evokes the usage of "all Israel" [πᾶς Ἰσραὴλ] in the Old Testament and non-canonical Jewish literature. For that I recommend an excellent article by James M. Scott, “All Israel Will Be Saved.”[1]

Scott shows that the phrase is typically used to describe all twelve tribes. In other words, the term is typically used to identify the inclusion of the northern tribes.

2 Samuel 2:8-10: Now Abner the son of Ner, commander of Saul's army, had taken Ish-bo'sheth the son of Saul, and brought him over to Mahana'im; and he made him king over Gilead and the Ash'urites and Jezreel and E'phraim and Benjamin and all Israel. Ish-bo'sheth, Saul's son, was forty years old when he began to reign over Israel, and he reigned two years. But the house of Judah followed David”

2 Samuel 5:3, 5: So all the elders of Israel came to the king at Hebron; and King David made a covenant with them at Hebron before the Lord, and they anointed David king over Israel… At Hebron he reigned over Judah seven years and six months; and at Jerusalem he reigned over all Israel and Judah thirty-three years.

2 Samuel 19:11: And King David sent this message to Zadok and Abi'athar the priests, "Say to the elders of Judah, 'Why should you be the last to bring the king back to his house, when the word of all Israel has come to the king?”

1 Chronicles 21:5: And Jo'ab gave the sum of the numbering of the people to David. In all Israel there were one million one hundred thousand men who drew the sword, and in Judah four hundred and seventy thousand who drew the sword.

1 Kings 4:7: Solomon had twelve officers over all Israel, who provided food for the king and his household; each man had to make provision for one month in the year.

In eschatological contexts, the term is especially focused on the restoration of the northern tribes with the southern house of Judah. Thus, "all Israel" means "all the tribes" of Israel--even the so-called "lost tribes". See, for example, the non-canonical book known as the Testament of Benjamin 10:11.

Therefore, my children, if you live in holiness, in accord with the Lord's commands, you shall again dwell with me in hope; all Israel will be gathered to the Lord."

For a detailed survey see James Scott's article (especially pp. 500-514).

The upshot of the analysis is that the term was related to Israel's tribal configuration. Scott states in his conclusion of the survey of Old Testament texts: "Although the term 'all Israel' can be used to denote a representative selection from the full complement of the tribes, it is never used to refer specifically to all individuals within the nation" (p. 507).

Peter's address to "the whole house of Israel" thus signals that the "Eleven"--once, the "Twelve Apostles"--are committed to their vocation, namely, to bring the Gospel to all twelve tribes of Israel.

I would suggest that they do this by going, ultimately, to the nations--it is there that the northern tribes had been scattered.*

Notably, elsewhere in Scripture the restoration of the twelve tribes from exile is described in terms of shepherding imagery. Here we have a tie-in with the Gospel reading (see below)

2. Salvation is through baptism. When the crowds are "cut to the heart", by Peter's sermon, they ask him a crucial question: "What are we to do, my brothers?" Peter's response is significant: "Repent and be baptized every one of you."

For Peter and the apostles, the proper response to the message of salvation is baptism. From the beginning, then, we see that salvation involves more than simply saying "the sinner's prayer". The restoration of Israel is accomplished through sacramental means. Indeed, we find something similar in 1 Peter where it is "baptism" that "now saves you" (1 Peter 3:21).

Here is not the proper place for a long drawn out discussion of sacramental theology. Suffice it to say, baptism illustrates that the faith that we receive by the gift of grace does not happen in an individualistic way. To be baptized means one is dependent on another; no one baptizes themselves! Faith is ecclesial. The mode of the reception of faith is also not simply determined by the whims of an individual. One receives faith through and in the whole body of Christ.

And, of course, our faith is continued to be nourished just as it was first received. Faith is maintained and strengthened through ecclesial communion.

3. 3,000 were added to their number. The number of converts won through Peter's sermon is not insignificant. However, to understand the imagery one must take a step back and understand the larger backdrop of the sermon itself.

In Acts 2, the giving of the Spirit at Pentecost is understood in terms reminiscent of the giving of the Law at Sinai in Exodus. In Acts 2, the coming of the Spirit is associated with a great sound, namely, mighty wind (Acts 2:2). This evokes the miraculous sound of a "loud trumpet blast" heard by Israel at Sinai (Ex. 19:16). Acts 2 also describes the Spirit's coming in terms of a vision of tongues of fire (Acts 2:3), imagery also reminiscent of Sinai (cf. Ex. 19:18). In addition, there is the appearance of miraculous speech in Acts 2; everyone understands the apostles in their own language (cf. Acts 2:4). This has a parallel in Exodus 19 as well; God speaks to Moses "in thunder" (Ex. 19:19).

Of course, after Israel received the law, Israel fell into the sin of idolatry. Moses commanded that the idolaters be executed. How many were executed? 3,000 (cf. Ex. 32:28). The same number of people who convert at the coming of the Spirit (cf. Acts 2:41).

The coming of the Spirit thus is similar to the giving of the Law but in one important way it goes beyond what happened at Sinai. The Spirit is given to empower believers to be righteous; through the Spirit, believers can now fulfill the just requirements of the law (to borrow language from Romans 8:4).

RESPONSORIAL PSALM: Psalm 23:1-2a, 3b-4, 5, 6

R/ (1) The Lord is my shepherd; there is nothing I shall want.or:R/ Alleluia.The LORD is my shepherd; I shall not want.

In verdant pastures he gives me repose;

beside restful waters he leads me;

he refreshes my soul.

R/ The Lord is my shepherd; there is nothing I shall want.or:R/ Alleluia.He guides me in right paths

for his name’s sake.

Even though I walk in the dark valley

I fear no evil; for you are at my side.

With your rod and your staff

that give me courage.

R/ The Lord is my shepherd; there is nothing I shall want.or:R/ Alleluia.You spread the table before me

in the sight of my foes;

you anoint my head with oil;

my cup overflows.

R/ The Lord is my shepherd; there is nothing I shall want.or:R/ Alleluia.Only goodness and kindness follow me

all the days of my life;

and I shall dwell in the house of the LORD

for years to come.

R/ The Lord is my shepherd; there is nothing I shall want.or:R/ Alleluia.

Psalm 23 is perhaps the most familiar of all of the psalms. Here are a few things to point out about this psalm.

Literary arrangement. The psalm appears to have a two-part structure: (1) Psalm 23:1–4: The Lord as Shepherd; Psalm 23:5–6: The Lord as gracious host. John Goldingay lays out the structure of the psalm this way:

a The Lord is my shepherd (third person; vv. 1–3)

b You are my shepherd (second person; v. 4)

b´ You are my host (second person; v. 5)

a´ The Lord is my host (third person; v. 6)[2]

Shepherd imagery. Although this goes against the grain, it is important to point out that being a “shepherd” did not always imply that a person had a gentle disposition (cf. 1 Sam 17:34–36).[3]

The duties of a shepherd included defending the flock against aggressors (Ps 80:1–3 [2–4]; Jer 31:10), feeding and watering sheep (Isa 40:11), and find pastures (Jer 9:10 [9]; 23:10; Joel 1:19–20; etc.).

Indeed, as in Israel, the term was frequently used image for kings in the ancient Near East (e.g., Hammurabi; Cyrus [Isa 44:28]). It was also used in other cultures for deities.[4]

All of these tasks the psalmist attributes to the Lord. Incidentally, the book of Ezekiel identifies as the Lord as a kind of good shepherd who cares for his flock, while the evil ones (the corrupt leaders of Israel) fail in their task (cf. Ezek. 34:1–31).

The Shepherd’s Tools. The psalm mentions both of the shepherd’s tools. These are worth reflection upon. The two tools are primarily

1) the rod

2) the staff.

The rod is a weapon, kept in belt. It was used for striking adversaries of the sheep unto death (Exod. 21:20). Notably, the imagery is also used in connection with the Davidic king in Psalm 2, who defeats his enemies with a rod (cf. Ps 2:9).

The staff brings comfort, but in different ways. The staff could be used by the shepherd to lean upon for support (Zech 8:4). It was also used to keep sheep in order and knock down fruit.

New Exodus Imagery. The imagery of God “shepherding” evokes exodus imagery.[5] Specifically, the Lord “leads” (cf. nāhal) in verse 2, language elsewhere linked with the Exodus.

“Thou hast led in thy steadfast love the people whom thou hast redeemed, thou hast guided [nāhal] them by thy strength to thy holy abode” (Exod 15:13).

The fact that the psalm uses such imagery may point to the hope for a new exodus. In fact, the psalm uses terminology that is explicitly linked with such hopes. For example, the psalmist speaks of how God brings “comfort”—a term the prophet Isaiah famously used to describe the hope for a New Exodus (Isa 40:31). Likewise, the psalm’s imagery of the Lord feeding his people, evokes Isaiah 49:

“He will feed his flock like a shepherd, he will gather the lambs in his arms, he will carry them in his bosom, and gently lead those that are with young” (Isa 49:11).

Moreover, new exodus hopes were typically tied to the temple, which was seen as the place Israel would be gathered at in the messianic age (e.g., Isa. 2:2). In light of the other new exodus themes, it may be significant that the psalm is ultimately ordered to temple climax (cf. v. 6: “I shall dwell in the house of the LORD for years to come.”)

The thanksgiving meal. The fact that the psalm moves from a celebration of the Lord protecting his people to a meal has also caused some scholars to link the psalm to the tôdâ, the thanksgiving sacrifice which stands as the backdrop to other psalms (cf., e.g., the superscription of Ps 100). Ernest Lucas writes,

“The ‘thanksgiving offering’ was one form of the ‘sacrifice of well-being’ in which only part of the animal was burnt on the altar and the rest cooked and eaten at the sanctuary by the offerer and guest. Such an occasion would be an appropriate one for reciting this psalm, which in its expression of confidence in God is also an implicit expression of thanks.”[6]

In this the psalm may also be evoking new exodus imagery. Of course, the exodus was closely associated with a Passover meal, a celebration ancient Jews closely linked with the thanksgiving sacrifice. The exodus also famously climaxed with a meal with God at Mt. Sinai (cf. Exod 24:11). As many scholars have noticed, that scene seems to be in the background of messianic banquet prophecies such as that found in Isa. 25:6-8. In short, the new exodus was typically linked with the idea of a great banquet—a meal like Passover in which God’s people rejoice in celebration at table.

That the psalm uses similar imagery reinforces the possibility that the “thank offering” is in view. Indeed, the thanksgiving sacrifice—which like the Passover, climaxed in a meal—is closely associated with the new exodus (cf., e.g., Jer. 33:11).

Christological reading. In Christian tradition, the psalm has been read as describing Christ, who is presented as the “good shepherd” in Scripture. Notably, such imagery is found in the second reading and in the Gospel selection.

Sacramental readings. In Christian tradition, the psalm has also been read sacramentally. St. Thomas Aquinas offers—in addition to a literal reading—such spiritual interpretations in his commentary on Psalm 23. The green pastures the shepherd brings his flock are understood in terms of spiritual food; e.g., eucharist. The restful waters the shepherd leads his people to are connected to baptism, as is the language of “anointing”. The language of the preparation of the “table” is also linked to the Eucharistic celebration as is the language of the “cup” that “overflows”.

The possible use of the thanksgiving meal imagery may also be linked to sacramental theology; the Greek word for "thanksgiving" is "eucharist".

SECOND READING: 1 Peter 2:20b-25

If you are patient when you suffer for doing what is good,

this is a grace before God.

For to this you have been called,

because Christ also suffered for you,

leaving you an example that you should follow in his footsteps.

He committed no sin, and no deceit was found in his mouth.

When he was insulted, he returned no insult;

when he suffered, he did not threaten;

instead, he handed himself over to the one who judges justly.

He himself bore our sins in his body upon the cross,

so that, free from sin, we might live for righteousness.

By his wounds you have been healed.

For you had gone astray like sheep,

but you have now returned to the shepherd and guardian of your souls.

The second reading here climaxes with the description of Christ as the shepherd of souls, imagery that reinforces the Responsorial Psalm and the Gospel reading.

The reading, however, highlights the way Christ is a shepherd--he gives us an example to follow.

In that capacity, Christ is depicted as a sacrifice. The language here draws heavily from Isaiah 53 and Psalm 89.

In an excellent post written for this site back in 2007, Brant discussed explained that some ancient Jewish rabbis read Psalm 89 as a description of the eschatological suffering which the Messiah himself would undergo. In particular, he looked at an image found at the end of the psalm which was picked up on by the rabbis and seen as a description of the Messiah’s eschatological sufferings: “they mock the footsteps of thy anointed” (Ps 89:51).

This is an important insight. This would seem to indicate a presence of expectations of a suffering Davidic Messiah in Jewish thought. Since it is hardly likely that this tradition was invented by Jewish writers after the Christian period, it seems more than likely that such hopes were present in Jesus’ day.

1 Peter's combination of Isaiah 53 and Psalm 89 hardly seems coincidental.

Scholars have long noted the relationship of the book of Isaiah―especially the latter part of the book―with the Psalter.[7] However, what is seldom noted is the interesting relationship between Psalm 89 and Isaiah 53. Both passages speak of the “servant” of the Lord (Ps 89:39 [40]; Isa 52:13; 53:11; Heb.: עבֶד). In both passages this “servant” is described as being pierced or wounded [the word is the same in Hebrew: חָלַל; Ps 89:39b (40b); Isa 54:14].

The two passages also share many other literary points of contact. Both Psalm 89 and Isaiah 54 describe Israel’s experience of exile in terms מְחִתָּה ― terror, destruction, ruin (Ps 89:40 [41]; Isa 54:14). Likewise in both contexts the strength of the Lord is described in terms of the strength or holiness of his arm (Ps 89:13-14; Isa 52:9). In addition, both contexts speak of lost “youth” (cf. Ps 89:45 [46]; Isa 54:4). One might also point out that the preceding psalm, Psalm 88, like Isaiah 53, speaks of one who is cut off:

Ps 88:6: I am reckoned among those who go down to the Pit; I am a man who has no strength, 5 like one forsaken among the dead, like the slain that lie in the grave [Heb. קבֶר] like those whom thou dost remember no more, for they are cut off [Heb.: גָּזַר] from thy hand

Isa 53:8-9: By oppression and judgment he was taken away; and as for his generation, who considered that he was cut off [Heb.: גָּזַר] out of the land of the living, stricken for the transgression of my people?... And they made his grave [Heb. קבֶר] with the wicked…

Although it is clear the psalms were arranged at a later date than their composition, one can hardly fail to note the similarities between these two passages. Indeed, scholars already view these psalms in terms of a unit.[8]

Peter’s use of Isaiah 53 and Psalm 89From what we have seen I think it at least appears plausible that Psalm 89 was understood in connection with the traditions present in Isaiah 53. Confirmation however is found in 1 Peter. There the various threads we have followed here intertwine.

1 Peter 2:22-25 clearly describes Christ’s suffering in connection with Isaiah 53:

“He committed no sin; no guile was found on his lips. 23 When he was reviled, he did not revile in return; when he suffered, he did not threaten; but he trusted to him who judges justly. 24 He himself bore our sins in his body on the tree, that we might die to sin and live to righteousness. By his wounds you have been healed. For you were straying like sheep, but have now returned to the Shepherd and Guardian of your souls.”

What is fascinating is that this allusion to Isaiah 53 is immediately preceded by what clearly seems to be an allusion to the image of the footsteps of the messiah in Psalm 89:51.

1 Pet 2:21: For to this you have been called, because Christ also suffered for you, leaving you an example, that you should follow in his steps.

Here Peter relates the sufferings of the Messiah Jesus to the very same passage the ancient rabbis read in connection with the eschatological sufferings of the Messiah. Indeed, much could be said about 1 Peter and the eschatological sufferings―recently an entire monograph was written developing this theme in the epistle.[9] Moreover, the image of the footsteps of the Messiah from Psalm 89:51 is seamlessly conflated with allusions to Isaiah 53.

Even more, Peter links the sufferings of Christians with Jesus’ sufferings―they must walk in his steps. In other words, whether or not Isaiah 53 describes an individual or the people of God would have been a moot point for Peter―for him it describes both, since Christians have a participation in the eschatological suffering of Christ. He thus goes on to say, “Since therefore Christ suffered in the flesh, arm yourselves with the same thought, for whoever has suffered in the flesh has ceased from sin… rejoice in so far as you share Christ’s sufferings, that you may also rejoice and be glad when his glory is revealed” (1 Pet 4:1, 13).

GOSPEL: John 10:1-10

Jesus said:

“Amen, amen, I say to you,

whoever does not enter a sheepfold through the gate

but climbs over elsewhere is a thief and a robber.

But whoever enters through the gate is the shepherd of the sheep.

The gatekeeper opens it for him, and the sheep hear his voice,

as the shepherd calls his own sheep by name and leads them out.

When he has driven out all his own,

he walks ahead of them, and the sheep follow him,

because they recognize his voice.

But they will not follow a stranger;

they will run away from him,

because they do not recognize the voice of strangers.”

Although Jesus used this figure of speech,

the Pharisees did not realize what he was trying to tell them.

So Jesus said again, “Amen, amen, I say to you,

I am the gate for the sheep.

All who came before me are thieves and robbers,

but the sheep did not listen to them.

I am the gate.

Whoever enters through me will be saved,

and will come in and go out and find pasture.

A thief comes only to steal and slaughter and destroy;

I came so that they might have life and have it more abundantly.”

1. Jesus as the true Shepherd. By speaking of his "sheep", Jesus, of course, uses language his audience would have been familiar with from the Old Testament. As seen above, Israel, the people of God, is described in terms of a flock.[10]

Numerous examples of this from the Old Testament could be mentioned. Two that come to mind are:

“Then he led forth his people like sheep, and guided them in the wilderness like a flock” (Ps 78:52).

“Hear the word of the Lord, O nations, and declare it in the coastlands afar off; say, ‘He who scattered Israel will gather him, and will keep him as a shepherd keeps his flock.’” (Jer 31:10)

Of course, different Old Testament figures are described as shepherds, including, Moses [11], David [12], and the Messiah [13]. Obviously, the primary shepherd of Israel is God.[14] Of course, John makes it clear that Jesus is not only the Messiah, the Son of David (John 1:49), but also that he is God (e.g., John 1:1).

2. An Allusion to Ezekiel 34 and a condemnation of the wicked leaders. By describing himself as the "good" shepherd Jesus seems to implicitly be calling attention to the the fact that the Jewish rulers are bad shepherds. The imagery here may likely evoke Ezekiel 34, a passage in which God condemns the wicked leaders of Israel as wicked shepherds. Their failure, the prophet explains, has led Israel to go into exile and be scattered among the nations. The prophecy ends goes on to announce the promise of the restoration of the twelve tribes under a future Davidic messiah: "And I will set up over them one shepherd, my servant David, and he shall feed them: he shall feed them and be their shepherd. And I, the Lord, will be their God, and my servant David shall be prince among them; I, the Lord, have spoken. (Ezek 34:23-24).

3. Christ as the Sheepgate. Jesus describes how he is the one gate through which the sheep enter the sheepfold. Sheepfolds built in different ways in Jesus' day. Essentially, these were different kinds of enclosures, including, a cave (1 Sam 24:3), a square hillside made of stone walls, a roof enclosure, etc.

A sheepfold was carefully guarded—only the shepherd was admitted. If the enclosure involved a stone wall, the gate would have been a heavy door in stone wall used by both people and animals. However, if the enclosure was a temporary shelter it would have had no permanent door; the shepherd would have simply slept across its opening (cf. 10:7–9). This might make sense of how Christ is both the shepherd and the "gate".

4. A sacrificial flock? Some have pointed out that the word translated "sheepfold" (aulē) was a term also used to describe the temple "court" (cf. Rev. 11:2) or the "courtyard" of the high priest (John 18:15). Perhaps this is insignificant.

Or perhaps the imagery is meant to echo imagery used elsewhere in John to describe Jesus as the true temple (cf., e.g., John 2:19-21). Is Jesus subtly suggesting that believers enter into him as the true temple as "sheep". Is the imagery here suggesting that the believers are meant to participate in his sacrifice? After all, Christ is elsewhere described as the sacrificial lamb of God in John's Gospel (cf. John 1:29).

One observation that may reinforce this imagery is the fact that Jesus goes on to describe how he lays down his life for his sheep (John 10:17)... and then describes how his sheep "follow me" (John 10:27).

5. Hearing the voice of the shepherd. The Pharisees do not understand Jesus' teaching, illustrating Jesus' point that his sheep hear his voice; the Pharisees do not belong to his flock.

Specifically, Christ explains that he calls his sheep "by name". The imagery points to the idea of intimacy (cf. Isa 43:1; 49:1).

To be a member of Christ's flock means to be able to hear his voice--and recognize it as Christ's. The imagery points to the importance of discernment and meditation.

Of course, in Catholic tradition, "hearing God's voice" is especially linked to meditation on Scripture. The Second Vatican Council explains, "“In the sacred books [of the Bible], the Father who is in heaven comes lovingly to meet his children, and talks with them” (Dei Verbum 21).

The Liturgy of the Word is crucial. It is here that we are given, "The Word of the Lord".

Let us ask God to give us ears to hear his voice in these readings so that we can go forward to meet him in eucharistic communion.

NOTES

*Here I agree with the essence of the argument put forward by Jason Staples, "What Do the Gentiles Have to Do with "All Israel"? A Fresh Look at Romans 11:25-27," Journal of Biblical Literature 130/2 (2011): 371-90

[1] In Restoration: Old Testament, Jewish and Christian Perspectives (ed. J. M. Scott; Leiden: Brill, 2001), 489-526.

[2] John Goldingay, Psalms (3 vols.; Baker Commentary on the Old Testament Wisdom and Psalms. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2006–8), 1:347.

[3] See also Midrash on Psalms 1:327.

[4] See ANET 69, 71, 72, 337, 387–88.

[5] See also Exod. 13:17, 21; 15:13; 32:34; Deut. 32:12; Neh. 9:12; Ps. 77:20 [21]; Ps. 78:14, 15.

[6] Ernest C. Lucas, Exploring the Old Testament: A Guide to the Psalms and Wisdom Literature (vol. 3 of the Old Testament; Downers Grove, 2003), 39.

[7] In particular, we might mention that Robert Cole has noted connections between Psalm 89 and Isaiah 55: “Both vv. 4 [of Psalm 89] (Davidic covenant) and 2-3 [of Psalm 89] (faithfulness and fidelity) are brought together in the one verse of Isa. 55:3 by parallel vocabulary... (v. 55:3cd).” Robert Cole, The Shape and Message of Book III (Psalms 73-89) (England: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000), 209 n. 17. In addition, see Norbert Lohfink, Der Gott Israels und die Völker – Untersuchungen zum Jesajabuch und zu den Psalmen (Stuttgarter Bibel Studien 154; Katholisches Bibelwerk, 1994).

[8] See for example Cole, The Shape and Message of Book III (Psalms 73-89), 177-230. For a fuller discussion of Psalm 89 and the Jewish interpretive tradition which understood it in connection with Isaiah 53, Zechariah 9, and Psalm 88, see the excellent discussion in David Mitchell, The Message of the Psalter: An Eschatological Programme in the Book of Psalms (JSOTSupS 252; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1997), 253-8.

[9] Mark Dubis, Messianic Woes in First Peter: Suffering and Eschatology in 1 Peter 4:12–19 (Studies in Biblical Literature 33; New York: Lang, 2002).

The image of Israel as God’s sheep or flock is found repeatedly: Ps 74:1; 77:20; 78:52; 79:13; 80:1; 100:3; Isa 49:9; 63:11; Jer 13:17; 31:10; Zech 9:16; 10:3; L.A.B. 23:12; 30:5; 1 En. 89:16–24; 4Q266 18 5.13; Sipre Deut. 15.1.1; Exod. Rab. 24:3; Pesiq. Rab. 9:2; 26:1/2. A handful of texts also describe God shepherding all his creation (cf. Sir 18:13; Philo, Agiculture 50–53; p. Ber. 2:7).

Ps 77:20; Isa 63:11; 1 En. 89:35; L.A.B. 19:3, 10; Sipre Deut. 305.3.1; p. Sanh. 10:1; Pesiq. Rab. Kah. 2:8; Exod Rab. 2:2; Tg. Ps.-J. on Gen 40:12 (Moses, Aaron and Miriam).

2 Sam 5:2; 1 Chr 11:2; Ps 78:70–72; Ezek 34:23; 37:24; 4Q504 4.6–8; Gen. Rab. 59:5.

Mic 5:4; Jer 23:1–6; Ezek 34:23; Pss. Sol. 17:40; cf. Zech 13:7; Tg. Neof. 1 on Exod 12:42 (New Moses).

Ps 23:1–4; 28:9; 74:1–2; 77:20; 78:52; 79:13; 80:1; 100:3; Isa 40:11; Jer 13:17; 31:10; Ezek 34:11–17; Mic 7:14; Zech 9:16; 10:3; Sir 18:13; 4Q509 4.24; 1 En. 89:18; L.A.B. 28:5; 30:5; Philo, Agriculture 50–53; b. Ḥag. 3b; Pesaḥ. 118a; Exod. Rab. 34:3; Lam. Rab. 1:17; Pesiq. Rab. 3:2.

[15] See Craig Keener, The Gospel of John: A Commentary (2 vols. Peabody: Hendrickson, 2003), 809

![]()