Posted on 12/21/2007 6:03:26 PM PST by BGHater

Edited on 12/21/2007 6:31:46 PM PST by Lead Moderator. [history]

In the era of computer-controlled surveillance, your every move could be captured by cameras, whether you're shopping in the grocery store or driving on the freeway. Proponents say it will keep us safe, but at what cost?

The ferry arrived, the gangway went down and 7-year-old Emma Powell rushed toward the Statue of Liberty. She climbed onto the grass around the star-shaped foundation. She put on a green foam crown with seven protruding rays. Turning so that her body was oriented just like Lady Liberty's, Emma extended her right arm skyward with an imaginary torch. I snapped a picture. Then I took my niece's hand, and we went off to buy some pretzels.

Other people were taking pictures, too, and not just the other tourists—Liberty Island, name notwithstanding, is one of the most heavily surveilled places in America. Dozens of cameras record hundreds of hours of video daily, a volume that strains the monitoring capability of guards. The National Park Service has enlisted extra help, and as Emma and I strolled around, we weren't just being watched by people. We were being watched by machines.

Liberty Island's video cameras all feed into a computer system. The park doesn't disclose details, but fully equipped, the system is capable of running software that analyzes the imagery and automatically alerts human overseers to any suspicious events. The software can spot when somebody abandons a bag or backpack. It has the ability to discern between ferryboats, which are allowed to approach the island, and private vessels, which are not. And it can count bodies, detecting if somebody is trying to stay on the island after closing, or assessing when people are grouped too tightly together, which might indicate a fight or gang activity. "A camera with artificial intelligence can be there 24/7, doesn't need a bathroom break, doesn't need a lunch break and doesn't go on vacation," says Ian Ehrenberg, former vice president of Nice Systems, the program's developer.

Most Americans would probably welcome such technology at what clearly is a marquee terrorist target. An ABC News/Washington Post poll in July 2007 found that 71 percent of Americans favor increased video surveillance. What people may not realize, however, is that advanced monitoring systems such as the one at the Statue of Liberty are proliferating around the country. High-profile national security efforts make the news—wiretapping phone conversations, Internet monitoring—but state-of-the-art surveillance is increasingly being used in more every-day settings. By local police and businesses. In banks, schools and stores. There are an estimated 30 million surveillance cameras now deployed in the United States shooting 4 billion hours of footage a week. Americans are being watched, all of us, almost everywhere.

We have arrived at a unique moment in the history of surveillance. The price of both megapixels and gigabytes has plummeted, making it possible to collect a previously unimaginable quantity and quality of data. Advances in processing power and software, meanwhile, are beginning to allow computers to surmount the greatest limitation of traditional surveillance—the ability of eyeballs to effectively observe the activity on dozens of video screens simultaneously. Computers can't do all the work by themselves, but they can expand the capabilities of humans exponentially.

Security expert Bruce Schneier says that it is naive to think that we can stop these technological advances, especially as they become more affordable and are hard-wired into everyday businesses. (I know of a local pizzeria that warns customers with a posted sign: "Stop stealing the spice shakers! We know who you are, we have 24-hour surveillance!") But it is also reckless to let the advances proceed without a discussion of safeguards against privacy abuses. "Society is fundamentally changing and we aren't having a conversation about it," Schneier says. "We are entering the era of wholesale surveillance."

Earlier this year, on a hot summer afternoon, I left my Brooklyn apartment to do some shoplifting.

I cruised the aisles of the neighborhood grocery store, a Pathmark, tossing items into my cart like a normal shopper would—Frosted Mini-Wheats, Pledge Wipes, a bag of carrots. Then I put them on the belt at checkout. My secret was on the lower level of the cart: a 12-pack of beer, concealed and undetectable. Or so I thought. Midway through checkout the cashier addressed me, no malice in her voice, but no doubt either. "Do you want to ring up that beer?"

My heist had been condoned by Pedro Ramos, Pathmark's vice president of loss prevention, though he didn't know precisely when or where I was going to attempt it. The beer was identified by an object-recognition scanner at ankle level—a LaneHawk, manufactured by Evolution Robotics—which prompted the cashier's question. Overhead, a camera recorded the incident and an alert was triggered in Ramos's office miles away on Staten Island. He immediately pulled up digital video and later relayed what he saw. "You concealed a 12-pack of Coronas on the bottom of the cart by strategically placing newspaper circulars so as to obstruct the view of the cashier."

Busted.

Pathmark uses StoreVision, a powerful video analytic and data-mining system. There are as many as 120 cameras in some stores, and employees with high-level security clearances can log on via the Web and see what any one of them is recording in real time. An executive on vacation in Brussels could spy on the frozen-food aisle in Brooklyn.

In 2006 theft and fraud cost American stores $41.6 billion, an all-time high. Employee theft accounted for nearly half of the total (shoplifting was only a third), so much of the surveillance aims to catch in-house crooks. If the cashier had given me the beer for free—employees often work with an outside accomplice—the system would know by automatically comparing what the video recorded with what the register logged. The technologies employed by Pathmark don't stop crime but they make a dent; weekly losses are reduced by an average of 15 percent.

Pathmark archives every transaction of every customer, and the grocery chain is hardly alone. Amazon knows what you read; Netflix, your taste in movies. Search engines such as Google and Yahoo retain your queries for months, and can identify searches by IP address—sometimes by individual computer. Many corporations log your every transaction with a stated goal of reducing fraud and improving marketing efforts. Until fairly recently it was impractical to retain all this data. But now the low cost of digital storage—you can get a terabyte hard drive for less than $350—makes nearly limitless archiving possible.

So what's the problem? "The concern is that information collected for one purpose is used for something entirely different down the road," says Ari Schwartz, deputy director of the Center for Democracy and Technology, a Washington, D.C., think tank.

This may sound like a privacy wonk's paranoia. But examples abound. Take E-ZPass. Drivers signed up for the system to speed up toll collection. But 11 states now supply E-ZPass records—when and where a toll was paid, and by whom—in response to court orders in criminal cases. Seven of those states provide information in civil cases such as divorce, proving, for instance, that a husband who claimed he was at a meeting in Pennsylvania was actually heading to his lover's house in New Jersey. (New York divorce lawyer Jacalyn Barnett has called E-ZPass the "easy way to show you took the offramp to adultery.")

On a case-by-case basis, the collection of surveillance footage and customer data is usually justifiable and benign. But the totality of information being amassed combined with the relatively fluid flow of that data can be troubling. Corporations often share what they know about customers with government agencies and vice versa. AT&T, for example, is being sued by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a San Francisco-based civil liberties group, for allowing the National Security Agency almost unlimited access to monitor customers' e-mails, phone calls and Internet browsing activity.

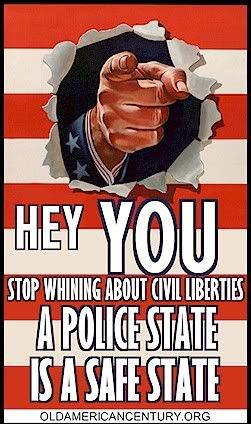

"We are heading toward a total surveillance society in which your every move, your every transaction, is duly registered and recorded by some computer," says Jay Stanley, a privacy expert with the American Civil Liberties Union.

In the late 18th century, English philosopher Jeremy Bentham dreamed up a new type of prison: the panopticon. It would be built so that guards could see all of the prisoners at all times without their knowing they were being watched, creating "the sentiment of an invisible omniscience," Bentham wrote. America is starting to resemble a giant panopticon, according to surveillance critics like Bob Barr, a former Republican congressman from Georgia. "Were Bentham alive today, he probably would be the most sought-after consultant on the planet," he recently wrote in a Washington Times op-ed.

One of the most popular new technologies in law enforcement is the license-plate reader, or LPR. The leading manufacturer is Remington-Elsag, based in Madison, N.C. Its Mobile Plate Hunter 900 consists of cameras mounted on the outside of a squad car and connected to a computer database in the vehicle. The plate hunter employs optical-character-recognition technology originally developed for high-speed mail sorting. LPRs automate the process of "running a plate" to check if a vehicle is stolen or if the driver has any outstanding warrants. The sensors work whether the police car is parked or doing 75 mph. An officer working the old-fashioned way might check a couple dozen plates a shift. The LPR can check 10,000.

New York's Long Beach Police Department is one of more than 200 agencies around the country that use LPRs, and I rode in a squad car with Sgt. Bill Dodge to see the technology at work. A computer screen mounted in front of the glovebox flashed black-and-white images of every photographed plate; low alarms, like the sounds of your character dying in an '80s video game, droned for the problem cars. Over the course of a couple of hours we didn't net any car thieves or kidnappers, but Dodge's LPR identified dozens of cars with suspended or revoked registrations. He said that the system doesn't violate anyone's privacy—"there's no magic technology that lets it see inside a garage"—and praised its fairness. "It doesn't matter if you're black, white, old, young, a man or a woman, the system cannot discriminate. It looks at everyone and everything."

In July, New York City officials unveiled the Lower Manhattan Security Initiative, modeled after London's "Ring of Steel," which will include license-plate readers, automated roadblocks and 3000 new surveillance cameras—adding to the 250 already in place. Chicago, meanwhile, which has 560 anti-crime cameras deployed on city streets, revealed plans in September to add a sophisticated IBM video analytic system that would automatically detect abandoned bags, suspicious behaviors (such as a vehicle repeatedly circling the Sears Tower) and vehicles sought by the police. Expanded surveillance is perhaps to be expected for these high-profile cities, but they're hardly alone. Richmond, Calif.; Spokane, Wash.; and Greenville, N.C., are among the cities that have recently announced plans to add electronic spying eyes. According to iSuppli, a market research firm, the global surveillance-camera business is expected to grow from $4.9 billion in 2006 to $9 billion in 2011.

The ability of cameras to deter criminals is unproven, but their value in helping to solve crimes is not. Recall how videos led to several arrests in the July 7, 2005, London subway bombings. The problem with surveillance video is that there's simply too much of it. "It's impossible for mere mortals with eyeballs and brains to process all the information we're gathering," says Stephen Russell, the chief executive of 3VR, a company that makes video analytic software.

An investigator looking for a particular piece of video is like a researcher working in a library with a jumbled card catalog—or in books with no tables of contents. The solution of 3VR and other similar companies is software that automatically analyzes and tags video contents, from the colors and locations of cars to the characteristics of individual faces that pass before the lens. The goal is to allow rapid digital search; instead of functioning like a shoddy library, 3VR hopes to be "the Google of surveillance video," Russell says. "It took 1000 [British agents] six weeks to review all the video after July 7. Had 3VRs been in place, it might have taken a dozen or so agents a weekend," he claims.

I recently spent a night at Chicago's Talbott Hotel, a luxurious small retreat where the staff addresses you by name and you have to clear a dozen pillows from the cushy king-size bed before lying down. The Talbott is surveilled by 70 cameras, which cover every public area of the hotel and feed into a 3VR system.

Troy Strand, general manager of the hotel, showed me a computer screen divided into 16 panes with different camera views. He looked up my check-in time and seconds later retrieved video of my arrival the previous day. There I was, towing my carry-on toward room 1504.

Strand found a few other shots showing me, then instructed the software to begin facial analysis. The system assessed the balance of light and dark areas of skin tone and hair and gauged the distance between my eyes, nose and mouth. Strand instructed the system to search for all recorded videos showing my face, and the computer retrieved several dozen faces, none of which was mine. There was a woman and a black man. But Strand went through a few pages of results, and I started to show up. When he clicked on any image, an associated video of me played—crossing the lobby to go to breakfast, chatting with the front-desk clerk.

So-called "facial profiling" has been surveillance's next big thing for nearly a decade, and it is only now showing tentative signs of feasibility. It's easy to see why people are seduced by the promise of this technology. Twelve bank companies employ 3VR systems at numerous locations, which build a facial template for every single person that enters any branch. If somebody cashes a check that is later determined to be stolen, the person's face can be flagged in the system, and the next time the con artist comes in, the system is supposed to alert the tellers.

For Strand, the security system's fancier features are just a bonus. The cameras are in plain sight, so he believes that would-be criminals and misbehaving employees are deterred. "You can't have security people on every floor monitoring every angle of the building," he says.

There's a man in Salt Lake City who knows what I did last summer. Specifically, he knows what I did on Aug. 24, 2007. He knows that I checked my EarthLink e-mail at 1:25 pm, and then blew a half an hour on ESPN's Web site. He also knows that my wife, Anne, wanted new shoes, from Hush Puppies or DSW, and that she synced her electronic planner—"she has quite a busy schedule," the man noted—and downloaded some podcasts. We both printed out passes for free weeklong trials at 24 Hour Fitness, but instead of working out, apparently spent the evening watching a pay-per-view movie. It was Bridge to Terabithia or Zodiac, he thinks.

The man's name is Joe Wilkinson, and he works for Raytheon Oakley Systems. The company specializes in "insider risk management," which means dealing with the problem of employees who, whether through innocent accident or nefarious plot, do things they really shouldn't be doing at work. Oakley's software, developed for the U.S. government and now used by ten Fortune 100 companies, monitors computer use remotely and invisibly. Wilkinson had agreed to run a surveillance trial with me as the subject, and after accessing my computer via the Web, he installed an "agent" that regularly reported my activities back to him.

The modern desktop machine is a multimedia distraction monster: friend, lover, shopping mall, stereo, television, movie theater and adult video store are mere mouse clicks away. Raytheon Oakley's software caught me wasting valuable work time checking personal e-mails and reading digital camera reviews online. Companies are also concerned about hostile work environments caused by employees openly surfing porn in the office—conse-quently, my 10:14 am visit to a risqué site was duly noted. Employees also leak trade secrets. (Consider the case of DuPont chemist Gary Min, who, after accepting a job with a competitor in 2005, raided DuPont's electronic library for $400 million worth of technical documents. He was caught by the FBI last year.) If I had downloaded any large engineering drawings onto a removable hard drive, Oakley's software would have alerted Wilkinson. And employees bad-mouth the boss. I wrote an e-mail to Anne that mentioned my editor at Popular Mechanics, Glenn Derene. Wilkinson rigged the software to flag anything with Derene's name, and alarm bells rang. Sorry, Glenn.

Surveillance of this sort is common. A 2005 survey by the American Management Association and the ePolicy Institute found that 36 percent of companies monitor workers on a keystroke-by-keystroke basis; 55 percent review e-mail messages, and 76 percent monitor Web sites visited. "Total Behavioral Visibility" is Raytheon Oakley's motto. The vice president of marketing, Tom Bennett, knows that some people fear workplace monitoring. But the technology has many positive aspects. "We are not Big Brother," he insists.

Employees are sometimes lazy or dishonest, but often they're simply careless. A parent who has to leave the office at midday to care for a sick child might copy sensitive company information onto a USB drive so that he can work at home. An account manager might carelessly send customer credit card numbers over an unsecured wireless network where they can be stolen. Bennett says that his company's software helps companies understand and improve how workers use their computers. The Oakley monitoring application works like a TiVo, allowing an instant video replay: where you pointed the mouse, when you clicked, what you wrote. This can catch the guilty but also exonerate the innocent, because the replay puts your actions in context.

The debate over surveillance pits the tangible benefits of saving lives and dollars against the abstract ones of preserving privacy and freedom. To many people, the promise of increased security is worth the exchange. History shows that new technologies, once developed, are seldom abandoned, and the computer vision systems being adopted today are transforming America from a society that spies upon a small number of suspicious individuals to one that monitors everybody. The question arises: Do people exercise their perfectly legal freedoms as freely when they know they're being watched? As the ACLU's Stanley argues, "You need space in your life to live beyond the gaze of society."

Surveillance has become pervasive. It is also more enduring. As companies develop powerful archiving and search tools, your life will be accessible for years to come in rich multimedia records. The information about you may be collected for reasonable purposes—but as its life span increases, so too does the chance that it may fall into unscrupulous hands.

Several months after I stayed at the Talbott Hotel, Derene, my editor, called Troy Strand to ask if he still had the security camera images of me at the hotel. He did. My niece Emma's Statue of Liberty shots are probably stored on a computer, as are the records of all my Pathmark purchases. Ramos could query my shopping trip of, say, Jan. 13, 2005, and replay video keyed precisely to any part of the register tape—from the fifth item scanned, pork chops, to the tenth, broccoli. That's innocuous and even humorous on the surface, but the more I thought about the store's power, the more it disturbed me.

"I would never do that," Ramos assured me. "But I could."

This is the true horror of our future.

Pinging the CW2 list, for future reference.

That's a joke. Get back to me when it's 99.9995 accurate.

You’re still as free as you ever were, right?

it's a complete denigration of the individual; the free-enterprise version of the nanny state.

soon service providers will develop personality scores and sell the data right along with your credit score.

And then we'll have an electronic caste system -- even more effective than the one we have already.

What price prosperity?

That stuff looks expensive. I hope we can afford it

“You are the dead,” repeated the iron voice.

“It was behind the picture,” breathed Julia.

“It was behind the picture,” said the voice.

“Remain EXACTLY where you are.

Make NO movement until you are ORDERED!”

George had everything right but the year.

Brilliant man, that Orwell.

I want to comment but I’m afraid to.

Shortly after I left, my cell phone rang. The manager of the restaurant told me that in that state it is illegal to leave a restaurant with an opened bottle of wine, that the restaurant's surveillance camera had me on videotape taking the bottle from the restaurant, and that, if I didn't return it at once, he would have to call the police to have me arrested.

It freaked me out.

I took the bottle back.

I made a mental note never to go to that restaurant again.

All this surveillance is enough to freak us all out!

Does this state have a name?

“go ahead”

How did he get your cell phone number?

He had taken my name and telephone number when I made reservations, several days before we went there for dinner. I’m not going to disclose the name of the restaurant or even of the state. I’m still freaked out!

How did he get your cell number?

How about those snickering watchers when you taste a bugger or any other act you don't someone else to see?

There are certain privacies around our human spaces, spaces within which we do our little oddities, harmless in themselves but subject to judgment, which can affect out lives through the attitude of others.

How many viewers might copy a particularly entertaining segment of recording of YOU in an inopportune moment and share with other officers?

Our behavior toward another depends a lot on our respect and contempt of them.

There are many ways a private recording of a person doing something that brings harm to no one can be used to harm that person by an enemy fortunate to obtain it.

Any law against viewing unauthorized recordings of private citizens can't regulate a willing sharer and sharee. But any damage will be done.

Politics, landing a client, getting a signature on a contract, getting a desired apartment, maintaining critical relationships, keeping a job, getting a job with a sought after employer? The list of potential harm is endless.

Not to mention the stress of being watched and having to act like a politically correct automation as you go about your personal business.

If you ain't doing nothing wrong, you ain't got nothing to worry about?

You got to worry about any idiot without personal morals, axes to grind, and eyes that don't check their personal prejudices and meanness at the door when they come on duty.

What price catching the occasional malum in se perpetrator in the act?

Ping.

This is sick. I know there are things out there you can cover the license plate with to foil cameras but that will only allievate part of the problem. We are becoming too smart for our own good between these cameras, genetic engineering and so on, at some point, we are about doe fo a smackdown, much like God did to the builders of the Tower of Babel. Still in the meantime, this does not bode well. I was listening to Mangino on WKBN, 570 kc, Youngstown, OH one morning and he said that most people will clamour for such cameras and in short, we will give up our privacy for security.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.