Skip to comments.

Free at Last. The Foreigner’s Gift

Commentary magazine ^

| Victor Davis Hanson

Posted on 09/02/2006 4:45:00 AM PDT by Valin

The Foreigner’s Gift: The Americans, the Arabs, and the Iraqis in Iraq by Fouad Ajami

Free Press. 400 pp. $26.00

Reviewed by Victor Davis Hanson

The last year or so has seen several insider histories of the American experience in Iraq. Written by generals (Bernard Trainor’s Cobra II, with Michael Wood), reporters (George Packer’s The Assassins’ Gate), or bureaucrats (Paul Bremer’s My Year in Iraq), each undertakes to explain how our enterprise in that country has, allegedly, gone astray; who is to blame for the failure; and why the author is right to have withdrawn, or at least to question, his earlier support for the project.

Fouad Ajami’s The Foreigner’s Gift is a notably welcome exception—and not only because of Ajami’s guarded optimism about the eventual outcome in Iraq. A Lebanese-born scholar of the Middle East, Ajami, now at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, lacks entirely the condescension of the typical in-the-know Western expert who blithely assures his American readers, often on the authority of little or no learning, of the irreducible alienness of Arab culture. Instead, the world that Ajami describes, once stripped of its veneer of religious pretense, is defined by many of the same impulses—honor, greed, self-interest—that guide dueling Mafia families, rival Christian televangelists, and (for that matter) many ordinary people hungry for power.

As an Arabic-speaker and native Middle Easterner, Ajami has enjoyed singular access to both Sunni and Shiite grandees, and makes effective use here of what they tell him. He also draws on a variety of contemporary written texts, mostly unknown by or inaccessible to Western authors, to explicate why many of the most backward forces in the Arab world are not in the least unhappy at the havoc wrought by the Sunni insurgency in Iraq. The result, based on six extended visits to Iraq and a lifetime of travel and experience, is the best and certainly the most idiosyncratic recent treatment of the American presence there.

_____________________

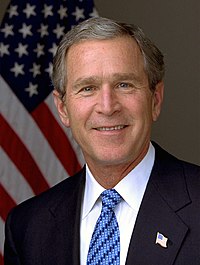

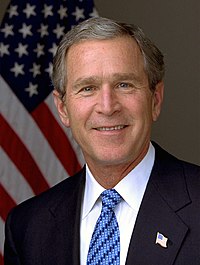

Ajami’s thesis is straightforward. What brought George W. Bush to Iraq, he writes, was a belief in the ability of America to do something about a longstanding evil, along with a post-9/11 determination to stop appeasing terror-sponsoring regimes. That the United States knew very little about the bloodthirsty undercurrents of Shiite, Sunni, and Kurdish sectarianism, for years cloaked by Saddam’s barbaric rule—the dictator “had given the Arabs a cruel view of history,” one saturated in “iron and fire and bigotry”—did not necessarily doom the effort to failure. The idealism and skill of American soldiers, and the enormous power and capital that stood behind them, counted, and still count, for a great deal. More importantly, the threats and cries for vengeance issued by various Arab spokesmen have often been disingenuous, serving to obfuscate the genuine desire of Arab peoples for consensual government (albeit on their own terms).

In short, Ajami assures us, the war has been a “noble” effort, and will remain so whether in the end it “proves to be a noble success or a noble failure.” Aside from the obvious reasons he adduces for this judgment—we have taken no oil, we have stayed to birth democracy, and we are now fighting terrorist enemies of civilization—there is also the fact that we have stumbled into, and are now critically influencing, the great political struggle of the modern Middle East.

The real problem in that region, Ajami stresses, remains Sunni extremism, which is bent on undermining the very idea of consensual government—the “foreigner’s gift” of his title. Having introduced the concept of one person/one vote in a federated Iraq, America has not only empowered the perennially maltreated Kurds but given the once-despised Iraqi Shiites a historic chance at equality. Hence the “rage against this American war, in Iraq itself and in the wider Arab world.” No wonder, Ajami comments, that a “proud sense of violation [has] stretched from the embittered towns of the Sunni Triangle in western Iraq to the chat rooms of Arabia and to jihadists as far away from Iraq as North Africa and the Muslim enclaves of Western Europe.” Sunni, often Wahhabi, terrorists have murdered many moderate Shiite clerics, taken a terrible toll of Shiites on the street, and, with the clandestine aid of the rich Gulf sheikdoms, hope to prevail through the growing American weariness at the loss in blood and treasure.

The worst part of the story, in Ajami’s estimation, is that the intensity of the Sunni resistance has fooled some Americans into thinking that we cannot work with the Shiites—or that our continuing to do so will result in empowering the Khomeinists in nearby Iran or its Hizballah ganglia in Lebanon. Ajami has little use for this notion. He dismisses the view that, within Iraq, a single volatile figure like Moqtadar al-Sadr is capable of sabotaging the new democracy (“a Shia community groping for a way out would not give itself over to this kind of radicalism”). Much less does he see Iraq’s Shiites as the religious henchmen of Iran, or consider Iraqi holy men like Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani or Sheikh Humam Hamoudi to be intent on establishing a theocracy. In common with the now demonized Ahmad Chalabi, Ajami is convinced that Iraqi Shiites will not slavishly follow their Khomeinist brethren but instead may actually subvert them by creating a loud democracy on their doorstep.

_____________________

In general, according to Ajami, the pathologies of today’s Middle East originate with the mostly Sunni autocracies that threaten, cajole, and flatter Western governments even as they exploit terrorists to deflect popular discontent away from their own failures onto the United States and Israel. Precisely because we have ushered in a long-overdue correction that threatens not only the old order of Saddam’s clique but surrounding governments from Jordan to Saudi Arabia, we can expect more violence in Iraq. What then to do? Ajami counsels us to ignore the cries of victimhood from yesterday’s victimizers, always to keep in mind the ghosts of Saddam’s genocidal regime, to be sensitive to the loss of native pride entailed in accepting our “foreigner’s gift,” and to let the Iraqis follow their own path as we eventually recede into the shadows.

Along with this advice, he offers a series of first-hand portraits, often brilliantly subtle, of some fascinating players in contemporary Iraq. His meeting in Najaf with Ali al-Sistani discloses a Gandhi-like figure who urges: “Do everything you can to bring our Sunni Arab brothers into the fold.” General David Petraeus, the man charged with rebuilding Iraq’s security forces, lives up to his reputation as part diplomat, part drillmaster, and part sage as he conducts Ajami on one of his dangerous tours of the city of Mosul. On a C-130 transport plane, Ajami is so impressed by the bookish earnestness of a nineteen-year-old American soldier that he hands over his personal copy of Graham Greene’s The Quiet American (“I had always loved a passage in it about American innocence roaming the world like a leper without a bell, meaning no harm”).

There are plenty of tragic stories in this book. Ajami recounts the bleak genesis of the Baath party in Iraq and Syria, the brainchild of Sorbonne-educated intellectuals like Michel Aflaq and Salah al-Din Bitar who thought they might unite the old tribal orders under some radical anti-Western secular doctrine. Other satellite figures include Taleb Shabib, a Shiite Baathist who, like legions of other Arab intellectuals, drifted from Communism, Baathism, and pan-Arabism into oblivion, his hopes for a Western-style solution dashed by dictatorship, theocracy, or both. Ajami bumps into dozens of these sorry men, whose fate has been to end up murdered or exiled by the very people they once sought to champion.

There are much worse types in Ajami’s gallery. He provides a vividly repugnant glimpse of the awful al-Ghamdi tribe of Saudi Arabia. One of their number, Ahmad, crashed into the south tower of the World Trade Center on 9/11; another, Hamza, helped to take down Flight 93. A second Ahmad was the suicide bomber who in December 2004 blew up eighteen Americans in Mosul. And then there is Sheik Yusuf al-Qaradawi, the native Egyptian and resident of Qatar who in August 2004 issued a fatwa ordering Muslims to kill American civilians in Iraq. Why not kill them in Westernized Qatar, where they were far more plentiful? Perhaps because they were profitable to, and protected by, the same government that protected Qaradawi himself. Apparently, like virtue, evil too needs to be buttressed by hypocrisy.

_____________________

The Foreigner’s Gift is not an organized work of analysis, its arguments leading in logical progression to a solidly reasoned conclusion. Instead, it is a series of highly readable vignettes drawn from Ajami’s serial travels and reflections. Which is hardly to say that it lacks a point, or that its point is uncontroversial—far from it. Critics will surely cite Ajami’s own Shiite background as the catalyst for his professed confidence in the emergence of Iraq’s Shiites as the stewards of Iraqi democracy. But any such suggestion of a hidden agenda, or alternatively of naiveté, would be very wide of the mark.

What most characterizes Ajami is not his religious faith (if he has any in the traditional sense) but his unequalled appreciation of historical irony—the irony entailed, for example, in the fact that by taking out the single figure of Saddam Hussein we unleashed an unforeseen moral reckoning among the Arabs at large; the irony that the very vehemence of Iraq’s insurgency may in the end undo and humiliate it on its own turf, and might already have begun to do so; the irony that Shiite Iran may rue the day when its Shiite cousins in Iraq were freed by the Americans.

When it comes to ironies, Ajami is clearly bemused that an American oilman, himself the son of a President who in 1991 called for the Iraqi Shiites to rise up and overthrow a wounded Saddam Hussein, only to stand by as they were slaughtered, should have been brought to exclaim in September 2003: “Iraq as a dictatorship had great power to destabilize the Middle East. Iraq as a democracy will have great power to inspire the Middle East.” Ajami himself is not yet prepared to say that Iraq will do so—only that, with our help, it just might. He needs to be listened to very closely.

Victor Davis Hanson is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution and the author most recently of A War Like No Other: How the Athenians and Spartans Fought the Peloponnesian War (Random House).

TOPICS: Foreign Affairs; Government; War on Terror

KEYWORDS: bookreiview; fouadajami; theforeignersgift; victordavishanson

1

posted on

09/02/2006 4:45:01 AM PDT

by

Valin

To: Tolik

2

posted on

09/02/2006 4:58:53 AM PDT

by

FreedomPoster

(Guns themselves are fairly robust; their chief enemies are rust and politicians) (NRA)

To: Valin

The long, dreadful night of subjugation of the people of the Middle East to despots, tyrants and cruel ideologies is not yet over, but at least a faint break of dawn is appearing at the horizon. How long this dawning must continue before the full light of day floods the plains and valleys of the Middle east, is a matter of will of the Western nations, which has been singularly lacking over the past several decades.

The will should be in two parts - one involving encouragement of economic and philosophical diversity among the people of the Middle East, and the other of making energy independence the goal of every Western nation, or any other nation that aspires to prosperity and civil order.

3

posted on

09/02/2006 5:05:10 AM PDT

by

alloysteel

(When in doubt, forge ahead anyway. To outsiders, it looks the same as boldness. Or plain crazy.)

To: Valin

I have always liked Ajami. He used to be a consultant for CBS and I used to watch Dan Rather every night. I know, I know. But one of the good things from those years was listening to this man. I just saw him on the BBC broadcast the other night. He had aged and I wouldn't have recognized him, but I recognised his voice. He's always interesting to listen to.

4

posted on

09/02/2006 5:10:09 AM PDT

by

twigs

To: twigs

I used to watch Dan Rather every night. I know, I know

That's ok, these things happen even in the best of families. :-)

5

posted on

09/02/2006 5:29:00 AM PDT

by

Valin

(http://www.irey.com/)

To: Valin

My daughter, then a toddler, knew who Rather was before any other public fighre. She'd toddle through at the end of the news and say, "Good night Dan." But the bright side is that I had the privilege to listen to Ajami. Always liked the man. A very reasonable voice.

6

posted on

09/02/2006 5:39:14 AM PDT

by

twigs

To: Valin

Beyond question the most important political fact in the Moslem "Middle East" is the Sunni - Shia split. Modernity and the West are not the direct cause of "Middle Eastern" friction. The Sunni - Shia split is.

The epicenter of Moslem politics is in Iraq. I see this center of gravity, this pivot point of history, in the Battle of Karbala. This huge battle at Karbala, a place sixty miles south west of Baghdad, solidified and made bitter the Sunni-Shiite divide.

The United States dominates this ground and therefore can control (unless the Left over here succeeds in imposing our defeat) the Sunni - Shia balance of power. We can keep either side from losing or from winning by our will. (Currently this means that Iran's nuclear weapons project must be be neutralized.)

Through diplomacy, and the whole operation since September 11 has been diplomacy in action, the ancient "middle eastern" world is changing dramatically. (By "diplomacy" I mean true and actual diplomacy and not the endless prattle of the UN and Foggy Bottom but instead the great persuasive power of our Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps and of the man who is very possibly the greatest American President ever.)

To reiterate, our enemies in this struggle are first and foremost and most dangerously domestic enemies. They are doing everything possible to turn victory into defeat.

7

posted on

09/03/2006 1:25:56 AM PDT

by

Iris7

(Dare to be pigheaded! Stubborn! "Tolerance" is not a virtue!)

To: Iris7

Beyond question the most important political fact in the Moslem "Middle East" is the Sunni - Shia split. Don't know enough to say that this is THE factor in the Arab world, and I'm not sure it's worth the effort to quantify which is the most important, but it is without a doubt A important issue.

By "diplomacy" I mean true and actual diplomacy

Links? Thanks.

8

posted on

09/03/2006 5:33:12 AM PDT

by

Valin

(http://www.irey.com/)

To: Valin; neverdem; Lando Lincoln; quidnunc; .cnI redruM; yonif; SJackson; dennisw; monkeyshine; ...

9

posted on

09/06/2006 12:37:50 PM PDT

by

Tolik

To: FreedomPoster

10

posted on

09/06/2006 12:38:27 PM PDT

by

Tolik

To: Valin

11

posted on

09/06/2006 1:46:20 PM PDT

by

TASMANIANRED

(The Internet is the samizdat of liberty..)

To: alloysteel

How long this dawning must continue before the full light of day floods the plains and valleys of the Middle east, is a matter of will of the Western nations, which has been singularly lacking over the past several decades.

The will should be in two parts - one involving encouragement of economic and philosophical diversity among the people of the Middle EastWhat diversity? All Muslimes are the same, and there are NO moderates. Don't you read FreeRepublic? </Deep Sarcasm>

12

posted on

09/06/2006 3:00:45 PM PDT

by

Stultis

To: Iris7; Valin

13

posted on

09/06/2006 7:55:15 PM PDT

by

bitt

("And an angel still rides in the whirlwind and directs this storm.")

To: Valin; Tolik

When it comes to ironies, Ajami is clearly bemused that an American oilman, himself the son of a President who in 1991 called for the Iraqi Shiites to rise up and overthrow a wounded Saddam Hussein, only to stand by as they were slaughtered, should have been brought to exclaim in September 2003: “Iraq as a dictatorship had great power to destabilize the Middle East. Iraq as a democracy will have great power to inspire the Middle East.” Ajami himself is not yet prepared to say that Iraq will do so—only that, with our help, it just might. He needs to be listened to very closely. Tolik – why do you suppose VDH did not nail it this time? Where’s the hammer and nail? Does this work not mate with your Weltanschauung? This work, in terms of history making historians, may be his masterpiece. Washington had Paine. Lincoln had Douglas. Who does GWB have? He has VDH – who has just introduced Ajami.

Let me share a personal story of great importance to me. This is an admission of an internal political conflict that I believe is loosely relevant. One cold day after GWB won his first Presidential Election – I lost a bet with a friend from the Sudan. It was a bet I proposed about American history. I’m not prone to betting nor do I often make them. Indeed gambling belittles the social perception of money, but I digress. To my point - I have an ideological connection to American history that doesn’t always fit my Weltanschauung. I bet $20 that GWB was the first son of an American President to become President. The election reeked of nepotism and I ignorantly dismissed it as implausible.

I obviously lost. I was angry that a single American family had two children serve as President in America – in my time. What are these politics, I thought. “Do Americans want to return to Monarchy?” I asked my friends. The Bush family would not become royalty in my time! No sir! The American infatuation with JFK’s Camelot was enough to make me ill. I was as adamant about how democracies should manifest their freedom – in terms of politics – as I am now. The reason why I was wrong about GWB is precisely why I lost the bet with my friend from the Sudan. While I was deeply invested in Middle Eastern politics before 9-11-01, I was less invested in my own nation’s history and ideology. The reality is, in America, we choose our ideological parents. Biology is important but rarely defining. Case in point, Benjamin Franklin’s son was a royalist. Franklin worked actively for American Independence. He naturally thought his son William, serving as the Royal governor of New Jersey, would agree with his views. William did not. William remained a Loyal Englishman. This caused a rift between father and son which was never healed.

In our post 9-11 world, I've been forced to consider the relationship between fathers and sons as American leaders. I've come to believe that GWB has chosen Abraham Lincoln as his ideological father. What I understand of Lincoln and GWB, they appear to share a similar Weltanschauung, albeit in an extremely different context. Lincoln forwarded America’s critical mission during its domestic phase. GWB has accepted the American mission in its international phase. His father was offered the same opportunity but declined it. That’s why I see GWB’s ideological father as Lincoln.

He has distinguished himself so completely from my original repulsion of nepotism, I am forced to ask "Who is his Fredrick Douglas"? Ajami?

14

posted on

09/06/2006 9:21:18 PM PDT

by

humint

(...err the least and endure! --- VDH)

To: humint

Very interesting. And thanks for the new word: Weltanschauung (had to look it up). VDH rights on so high level that its hard sometimes to say that one essay is more exceptional than other. Just a judgement call with a view not to overburden the ping list constituency and not to run up inflation of the "hammer and nail".

15

posted on

09/07/2006 5:17:26 AM PDT

by

Tolik

Disclaimer:

Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual

posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its

management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the

exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.

FreeRepublic.com is powered by software copyright 2000-2008 John Robinson

Victor Davis Hanson reviews Fouad Ajami's new book The Foreigner’s Gift: The Americans, the Arabs, and the Iraqis in Iraq (with the “foreigner’s gift” being the very idea of consensual government)

Victor Davis Hanson reviews Fouad Ajami's new book The Foreigner’s Gift: The Americans, the Arabs, and the Iraqis in Iraq (with the “foreigner’s gift” being the very idea of consensual government)