Posted on 08/23/2012 4:22:41 AM PDT by Homer_J_Simpson

John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1936-1945

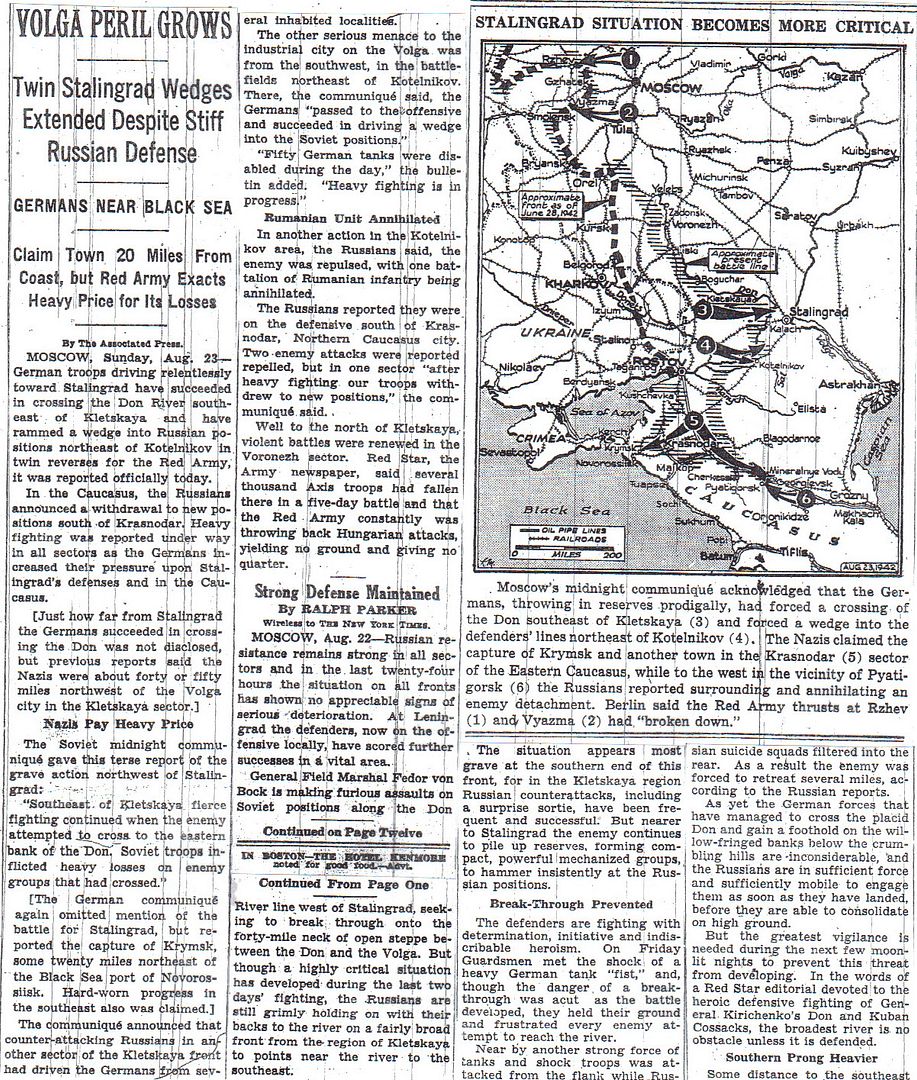

The News of the Week in Review

Twenty News Questions – 9

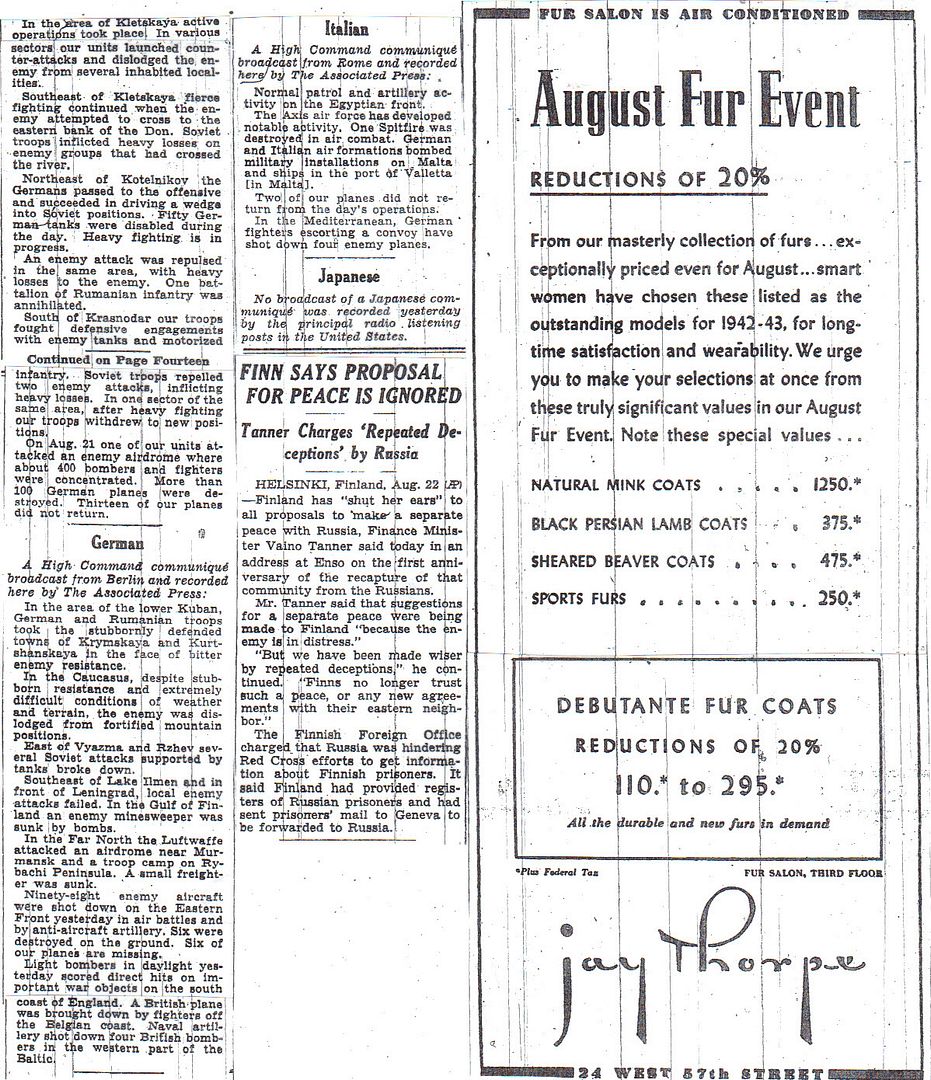

Allied Strategy Links Russia and Middle East (Baldwin) – 10

Caucasus and Middle East-Vital in Allied War Effort (map) – 11

Answers to Twenty News Questions – 12

http://www.onwar.com/chrono/1942/aug42/f23aug42.htm

German Army Group B on Volga

Sunday, August 23, 1942 www.onwar.com

German mountain troops on the summit of Mount Elbus [photo at link]

On the Eastern Front... German Army Group B reaches the Volga controlling a five mile front between Rynak and Erzovka. Soviet resistance is heavy. Meanwhile in the Caucasus, German mountain troops reach the summit of Mount Elbus, but do not control the area. The mountain valleys and passes are heavily defended by locals reinforced by units of the Red Army.

In the Solomon Islands... . In an attempt to cover the ferrying of supplies to their forces at Guadalcanal, both the Japanese and the American send major warships.

http://homepage.ntlworld.com/andrew.etherington/frame.htm

August 23rd, 1942

ÉIRE: A Luftwaffe Ju 88 and an RAF Spitfire Mk. V crash after they shoot each other down. The Spitfire, assigned to No. 315 (Polish) Squadron based at Ballyhalbert, County Down, Ireland, crashes at Ratoath, County Meath; the pilot, Sergeant Sawiak, is taken to the hospital but dies of his injuries. The Ju 88 crashes at Touger, County Waterford; one of the four man crew is injured. The four Germans are interned for the rest of the war. (Jack McKillop)

UNITED KINGDOM: Prime Minster Winston Churchill accepts President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s proposal that the U.S. operate Persian Gulf facilities for aid to USSR. (Jack McKillop)

Destroyer HMS Blean commissioned. (Dave Shirlaw)

U.S.S.R.: After a year-long siege of the city, Hitler orders the final attack on Leningrad (Operation Nordlicht). (Jack McKillop)

A battle group of the 16th Panzer Division and the 3rd and 60th Infantry Divisions rapidly advances from the Don River, reaching the west bank of the Volga River between Rynak and Erzovka north of Stalingrad.

At Izbushensky in the bend of the River Don, the Italian Savoia Cavalry, made up of 600 mounted men, counter attack Soviet Army units comprised of 2,000 men with mortar and artillery support. One cavalry squadron attacks head on, while the other, possessing only sabers, rides behind the enemy lines on horseback. They completely catch the Soviets by surprise and overrun the Soviet position. This last calvary attack of World War II resulted in the destruction of 2 Soviet battalions, another battalion forced to withdraw and the capture of 500 POW’s, 4 large artillery pieces, 10 Mortars, and 50 machine guns. (Jack McKillop)

Six hundred Luftwaffe bombers attack Stalingrad as the battle for the city begins. Incendiaries dropped by the German bombers burn three-quarters of Stalingrad to the ground; 40,000 Russians are killed. (Jack McKillop)

Soviet submarine SC-208 sunk by mines. All hands lost. (Dave Shirlaw)

USN heavy cruiser USS Tuscaloosa (CA-37), escorted by destroyers USS Rodman (DD-456) and USS Emmons (DD-457) and British destroyer HMS Onslaught, arrives at Murmansk, and disembarks men and unloads equipment from two RAF Bomber Command squadrons that have been transferred to Northern Russia. The ships depart the following day to return to the British fleet base at Scapa Flow, Orkneys. (Jack McKillop)

AUSTRALIA: USAAF P-40s of the Allied Air Forces shoot down 7 IJN bombers and 8 A6M “Zekes” over Darwin, Northern Territory, between 1205 and 1245 hours.

The unit was the 49th Fighter Group which was tasked with the air defence of the Darwin area. It was one helluva unit. During May 1942, the 49th shot down 38 Japanese aircraft vs. the loss of 7 P-40s and 3 pilots. A lot of the credit for these victories belonged to the ground crews and other service personnel which usually kept 60 P-40s in commission which means the 49th was rarely outnumbered. After every combat, a critique was held with the pilots to overcome the inferior speed, manoeuvrability, climb and ceiling of the P-40. The 2-plane element was adopted, individual dogfighting was banned and they were only to attack when they had an altitude advantage. Otherwise, everything that the AVG had learned was adopted by the 49th. (Jack McKillop)

GILBERT ISLANDS: Japanese light cruiser HIJMS Yubari, accompanied by four destroyers and supporting ships, shells Nauru Island in preparation for landings there. (Jack McKillop)

PACIFIC OCEAN: US Admiral Fletcher with TF 61 and Japanese Admiral Nagumo with the units of the IJN begin skirmishes which will result in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons. The US force is built around 3 fleet carriers and the IJN force is built around 2 fleet carriers and one escort carrier. These units of the IJN are charged with a mission of delivering additional troops and supplies in a convoy to Guadalcanal. This will develop into the 3rd carrier vs. carrier battle of the war.

Destroyer USS Blue scuttled after being torpedoed by the Japanese destroyer Kawakaze in Savo Sound, Solomons the day before. 9 crewmembers lost their lives.

A lone USAAF B-17 Flying Fortress of the Allied Air Forces bombs Buka Island.

Meanwhile, 5 IJN battle groups begin a complex plan to land IJA reinforcements on Guadalcanal. Included in the Japanese force are 2 fleet carriers, HIJMS Shokaku and HIJMS Zuikaku and the light aircraft carrier HIJMS Ryujo. US aircraft carriers in the area are USS Enterprise (CV-6), USS Saratoga (CV-2) and USS Wasp (CV-7).

USN search planes find two IJN submarines at 0725 and 0815 hours and a PBY-5 Catalina of a detachment of Patrol Squadron Twenty Three (VP-23) operating from Santa Cruz Island, spots IJN transports at 0950 hours. A strike is launched by the USS Saratoga at 1410 hours consisting of 31 SBD Dauntlesses and 6 TBF Avengers but the Japanese had reversed course due to bad weather and the USN strike force, unable to find the transports, lands on Henderson Field for the night. At 1800 hours, USS Wasp, low on fuel, retires from the area to refuel.

U.S.A.: In baseball, former Washington Senators pitcher (1907-1927) Walter Johnson pitching to former New York Yankees star (1920-1934) Babe Ruth is the pregame attraction that draws 69,000 fans for the New York-Washington game at Yankee Stadium in New York City. The large turnout provides US$80,000 (US$889,000 in year 2002 dollars) for Army-Navy relief. Ruth hits the fifth pitch into the right-field stands, and then adds one more shot before circling the bases. Sixteen Army-Navy relief games contribute $523,000 (US$5.8 million in year 2002 dollars) during the season. (Jack McKillop)

Escort carriers USS Croatan and Prince William launched. (Dave Shirlaw)

ATLANTIC OCEAN: U-506 sank SS Hamla. (Dave Shirlaw)

RIGHT through the middle of Stalingrad runs the river Tsaritsa.

Its deep gorge divides the city into a northern and a southern half. The Tsaritsa kept its name when Tsaritsyn became Stalingrad, and it still bears its name to-day now Stalingrad has become Volgograd. In 1942 the famous or notorious gorge of the Tsaritsa formed the junction between Hoth's and Paulus's Armies. Along it the inner wings of the two Armies were to advance swiftly through the city as far as the Volga. Everything seemed to suggest that the enemy was fighting rearguard actions only and was about to abandon the city.

Marshal Chuykov's memoirs reveal the disastrous situation in which the two Soviet Armies in Stalingrad found themselves following the surrender of the approaches to the city. Even experienced commanders did not rate Stalingrad's chances high.

General Lopatin, the Commander-in-Chief of the Sixty-second Army, was of the opinion that the city could not be held. He therefore decided to abandon it.

But when he tried to give effect to his decision the Chief of Staff, General Krylenko, refused his consent and sent an urgent message to Khrushchev and Yeremenko.

Lopatin was relieved of his command, although he was anything but a coward.

Lopatin's decision is not hard to understand if one reads Chuykov's account of the situation before Stalingrad. Chuykov writes: "It was bitter to have to surrender these last few kilometres and metres outside Stalingrad, and to have to watch the enemy's superiority in numbers, in military skill, and in initiative."

The Marshal describes how the machine operators of the State farms, where the various headquarters of Sixty-fourth Army had been set up, were sneaking off to safety.

"The roads to Stalingrad and to the Volga were jammed.

The families of collective farmers and State farm workers were on the move, complete with their livestock. They were all making for the Volga crossings, driving their animals in front of them and carrying their chattels on their backs.

Stalingrad was in flames.

Rumors that the Germans were in the city already added to the panic."

That then was the situation. But Stalin was not prepared to surrender his city without bitter struggle. He had sent one of his most reliable supporters, an ardent Bolshevik, to the front as the Political Member of the Military Council, with orders to inspire the Armies and the civilian population to fight to the end—Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev.

For the sake of Stalin's city he made self-sacrifice a point of honor for every Communist.

Lieutenant-General Platanov's three-volume documentary history of the Second World War contains several figures illustrating the situation: 50,000 civilian volunteers were incorporated in the "People's Guard";

75,000 inhabitants were assigned to Sixty-second Army;

3000 young girls were mobilized for service as nurses and as telephone and radio operators;

7000 Komsomol members between thirteen and sixteen were armed and absorbed in the fighting formations.

Everybody became a soldier. Workers were ordered to the battlefield with the weapons they had just produced in their factories. The guns made in the Red Barricade ordnance factory went into position in the factory grounds straight from the assembly line and opened fire on the enemy. The guns were manned by the factory workers.

On 12th September Yeremenko and Khrushchev entrusted General Chuykov with the command of Sixty-second Army, which had been led since Lopatin's dismissal by the Chief of Staff, Krylenko, and charged him with the defense of the fortress on the Volga.

It was an excellent choice. Chuykov was the best man available—hard, ambitious, strategically gifted, personally brave, and incredibly tough. He had no share in the Red Army's disasters of 1941 because at that time he had still been in the Far East. He was an unspent force, and he was not haunted by past calamities, as were so many of his comrades.

On 12th September, at 1000 hours sharp, Chuykov reported to Khrushchev and Yeremenko at Army Group headquarters in Yamy, a small village on the far, left bank of the Volga.

It is interesting that the talking was done by Khrushchev and not by Yeremenko, the military boss.

According to Chuykov's memoirs, Khrushchev said: "General Lopatin, the former C-in-C Sixty-second Army, believes that his Army cannot hold Stalingrad. But there can be no more retreat. That is why he has been relieved of his post. In agreement with the Supreme Commander-in-Chief, the Military Council of the Front invites you, Comrade Chuykov, to assume command of Sixty-second Army. How do you see your task?"

"The question took me by surprise," Chuykov records, "but I had no time to consider my reply. So I said, 'The surrender of Stalingrad would wreck the morale of our people. I swear not to abandon the city. We shall hold Stalingrad or die there.'

N. S. Khrushchev and A. I. Yeremenko looked at me and said that I had correctly understood my task."

Ten hours later Seydlitz's Corps launched its attack against Stalingrad Centre.

Chuykov's Army headquarters on Hill 102 was shattered by bombs, and the general had to withdraw to a dug-out in the Tsaritsa gorge, close by the Volga, complete with his staff, cook, and serving-girl.

On the following day, 14th September, General von Hartmann's men of 71st Infantry Division were already inside the city.

In a surprise drive they pushed through to the city centre and even gained a narrow corridor to the Volga bank.

At the same hour the Panzer Grenadiers of 24th Panzer Division stormed south of the Tsaritsa gorge through the streets of the old city, of ancient Tsaritsyn, captured the main railway station, and on 16th September likewise reached the Volga with von Heyden's battalion.

Between Beketovka and Stalingrad, in the suburb of Kuporoznoye, units of 14th Panzer Division and 29th Motorized Infantry Division had been established since 10th September, cutting off the city and the river from the south. Only in the northern part of the city was Chuykov still able to hold on. "We've got to gain time," he said to his commanders. "Time to bring up reserves, and time to wear out the Germans."

"Time is blood," he remarked, thus modifying the American motto "Time is money."

Indeed, time was blood. The battle of Stalingrad was epitomized in this phrase. Glinka, Chuykov's cook, heaved a sigh of relief when he got to his kitchen in the new dug-out. Above him was thirty feet of undisturbed earth. Happily he observed to the general's serving-girl, "Tasya, my little dove, we shan't get any shell-splinters dropping into our soup down here. There's no shell that will go through this ceiling."

"But there is," replied Tasya, who knew Glinka's fears. "A one-ton bomb would crash through all right—the general said so himself."

"A one-ton bomb—are there many of those?" the cook asked anxiously.

Tasya reassured him. "It would be a chance in a million; it would have to drop directly on our dug-out. That's what the general said."

The noise of the front came only as a distant rumble into the deep galleries. Ceiling and walls were neatly clad with boards. There were dozens of underground rooms for the personnel of Army headquarters. Right in the centre was a big room for the general and his chief of staff. One exit of this so-called Tsaritsyn dug-out, built during the preceding summer as a headquarters for the Army Group, led into the Tsaritsa gorge, closed by the steep bank of the Volga, while the other opened into Pushkin Street.

Nailed to the boarded wall of Chuykov's office was a hand-drawn city plan of Stalingrad, nearly ten feet high and six feet wide—the General Staff map of the battle.

These were no longer fronts in the hinterland; the scale of the battle maps was no longer in kilometres but in metres.

It was a matter of street corners, blocks, and individual buildings.

General Krylov, Chuykov's chief of staff, was entering the latest situation reports—the German attacks in blue, the Russian defensive positions in red. The blue arrows were getting closer and closer to the battle headquarters.

"Battalions of the 71st and 295th Infantry Divisions are furiously attacking Mamayev Kurgan and the main railway station.

They are being supported by 204th Panzer Regiment, which belongs to 22nd Panzer Division. The 24th Panzer Division is fighting outside the southern railway station," Krylov reported.

Chuykov stared at the plan of the city. "What has become of our counter-attacks?"

"They petered out. German aircraft have been over the city again since daybreak. They are pinning down our forces everywhere."

A runner came in with a situation sketch from the commander of 42nd Rifle Brigade, Colonel Batrakov. Krylov picked up his pencil and drew a semicircle around the battle headquarters. "The front is still half a mile away from us, Comrade Commander-in-Chief," he announced in a deliberately official manner.

Only half a mile.

The time was 1200 hours on 14th September. Chuykov knew what Krylov was implying. They had one tank brigade left as a last reserve, with nineteen T-34s. Should it be sent into action?

"What's the situation like on the left wing of the southern city?" Chuykov asked.

Krylov extended the blue arrow indicating the German 29th Motorized Infantry Division beyond Kuporoznoye. The suburb had fallen.

General Fremerey's Thuringians were pushing on, in the direction of the grain elevator.

The sawmills and the food cannery were already inside the German lines. Only from the southern landing-stage of the ferry to the tall grain elevator was there still a Soviet defensive line.

Chuykov picked up the telephone and rang up Army Group. He described the situation to Yeremenko. Yeremenko implored him: "You must hold the central river port and the landing-stage at all costs. The High Command is sending you the 13th Guards Rifle Division. This is 10,000 men strong and a crack unit. Hold the bridgehead open for another twenty-four hours, and try also to defend the landing-stage of the ferry in the southern part of the city."

Beads of sweat stood on Chuykov's forehead. The air in the gallery was suffocating.

"All right then, Krylov, scrape together anything you can find; turn the staff officers into combat-group commanders. We've got to hold the crossing open for Rodimtsev's Guards."

The last brigade with its nineteen tanks was thrown into the fighting—one battalion in front of the Army headquarters, from where the central railway station and main river port could also be covered, and another into the line between the grain elevator and the southern landing-stage.

At 1400 hours Major-General Rodimtsev, a legendary commander in the field and Hero of the Soviet Union, turned up at headquarters, bleeding and covered in dirt. He had been chased by German fighter-bombers. He reported that his division was standing by on the far bank and would cross the Volga at night.

Frowning, he gazed at the blue and red lines on the town plan.

At 1600 hours Chuykov again spoke to Yeremenko on the telephone. There were five hours to go before nightfall. In his memoirs Chuykov describes his feelings during those five hours: "Would our shattered and battered units and fragments of units in the central sector be able to hold out for another ten or twelve hours? That was my main worry at the time. If the men and their officers were to prove unequal to this well-nigh superhuman task the 13th Guards Rifle Division would not be able to cross over, and would merely witness a bitter tragedy."

Shortly before dusk Major Khopka, commander of the last reserves employed in the river port area, appeared at headquarters.

He reported: "One single T-34 is still capable of firing, but no longer of moving. The brigade is down to 100 men."

Chuykov regarded him coldly: "Rally your men around the tank and hold the approaches to the port. If you don't hold out I'll have you shot."

Khopka was killed in action; so were half his men. But the remainder held out.

Night came at last.

All the staff officers were in the port. As the companies of Rodimtsev's Guards Division came across the Volga they immediately went into action at the main points of defense in order to check the advance of 71st Infantry Division and to hold the 295th Infantry Division on the Mamayev Kurgan, the dominating Hill 102.

Those were crucial hours. Rodimtsev's Guards prevented Stalingrad Centre from being taken by the Germans on 15th September. Their sacrifice saved Stalingrad. Twenty-four hours later the 13th Guards Rifle Division had been smashed, bombed to smithereens by Stukas and mown down by shells and machine-gun fire.

In the southern city, too, a Guards division was fighting— the 35th under Colonel Dubyanskiy. Its reserve battalions were brought across by ferry from the left bank of the Volga to the southern landing-stage and immediately employed against spearheads of 29th Motorized Infantry Division in order to hold the line between the landing-stage and the grain elevator.

But the Stukas of Lieutenant-General Fiebig's VIII Air Corps pounded the battalions with bombs, and the remainder were crushed between the jaws of 94th Infantry Division and 29th Motorized Infantry Division. Only in the grain elevator, which was full of wheat, did fierce fighting continue for some time: it was a huge concrete block, as solid as a fortress, and every floor was furiously contested. It was there that assault parties and engineers of 71st Infantry Regiment were in action against the remnants of the Soviet 35th Guards Rifle Division amid the smoke and stench of the smoldering grain.

In the morning of 16th September the situation again looked bad on Chuykov's city plan. The 24th Panzer Division had conquered the southern railway station, wheeled westward, and shattered the defenses along the edge of the city and the hill with the barracks. Costly fighting continued on Mamayev Kurgan and at the main railway station. Chuykov telephoned Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev, Member of the Army Group's Military Council: "A few more days of this kind of fighting and the Army will be finished. We have again run out of reserves. There is absolute need for two or three fresh divisions."

Khrushchev got on to Stalin. Stalin released two fully equipped crack formations from his personal reserve—a brigade of marines, all of them tough sailors from the northern coasts, and an armored brigade.

The armored brigade was employed in the city centre around the main river port in order to hold open the supply pipeline of the front. The marines were employed in the southern city. These two formations prevented the front from collapsing on 17th September.

On the same day the German High Command transferred to Sixth Army the complete authority over all German formations engaged on the Stalingrad front. Thus the XLVIII Panzer Corps was detached from Hoth's Fourth Panzer Army and placed under General Paulus's command.

Hitler was getting impatient: "This job's got to be finished: the city must finally be taken."

Why the city was not taken, even though the German tankmen, grenadiers, engineers, Panzer Jägers, and flak troops fought stubbornly for each building, is explained by the following figures. Thanks to Khrushchev's determined fight for the Red Army's last reserves, Chuykov received one division after another between 15th September and 3rd October—altogether six fresh and fully equipped infantry divisions. They were fully rested formations, two of them Guards divisions. All these forces were employed in the ruins of Stalingrad Centre and in the factories, workshops, and industrial settlements of Stalingrad North, which had all been turned into fortresses. The German attack on the city was conducted, during the initial stage, with seven divisions—battle-weary formations, weakened by weeks of fighting between Don and Volga. At no stage were more than ten German divisions employed simultaneously in the fighting for the city.

True enough, even the once so vigorous Siberian Second Army was no longer quite so strong during the first phase of the battle. Its physical and moral strength had been diminished by costly operations and withdrawals. At the beginning of September it still consisted, on paper, of five divisions and five armored and four rifle brigades—a total of roughly nine divisions. That sounds a lot, but the 38th Mechanized Brigade, for instance, was down to a mere 600 men and the 244th Rifle Division to a mere 1500—in other words, the effective strength of a regiment.

No wonder General Lopatin did not think it possible to defend Stalingrad with this Army, and instead proposed to surrender the city and withdraw behind the Volga.

But determination counts for a great deal, and the fortunes of war, which so often follow the vigorous commander, have tipped the scales in more than one battle in the past. By 1st October Chuykov, Lopatin's successor, already had eleven divisions and nine brigades—i.e., roughly fifteen and a half divisions—not counting Workers' Guards and militia formations.

On the other hand, the Germans enjoyed superiority in the air. General Fiebig's well-tried VIII Air Corps flew an average of 1000 missions a day.

Chuykov in his memoirs time and again emphasizes the disastrous effect which the German Stukas and fighter-bombers had upon the defenders.

Concentrations for counter-attack were smashed, road-blocks shattered, communication lines severed, and headquarters leveled to the ground.

But what use were the successes of the "flying artillery" if the infantry was too weak to break the last resistance?

Admittedly the Sixth Army was able, following the settling down of the situation on the Don, to pull out the 305th Infantry Division and to use it later for relieving one of the worn-out divisions of LI Army Corps. But General Paulus did not receive a single fresh division.

With the exception of five engineer battalions, flown out from Germany, all the replacements he received for his bled-white regiments had to come from within the Army's zone of operations.

In the autumn of 1942 the German High Command had no reserves whatever left on the entire Eastern Front.

Serious crises had begun to loom up in the areas of all the Army Groups from Leningrad down to the Caucasus. In the north Field-Marshal von Manstein was compelled to use the bulk of his former Crimean divisions for counterattacks against Soviet forces which had penetrated deeply into the German front.

After fierce defensive fighting on the Volkhov, continuing until 2nd October, Army Group North was forced to gain a little breathing-space for itself in the first battle of Lake Ladoga. In the Sychevka—Rzhev area Colonel-General Model had to employ all his skill and all his forces in order to ward off Russian break-through attempts. He had to stand up to three Soviet Armies.

In the centre and on the southern wing of the Central Front, Field-Marshal von Kluge likewise had to employ all his forces to prevent a break-through towards Smolensk.

In the passes of the Caucasus and on the Terek, finally, the Armies of Army Group A were engaged in a desperate race against the threatening winter, trying once more, with a supreme effort, to get through to the Black Sea coast and the oilfields of Baku.

In France, Belgium, and Holland, on the other hand, there were a good many divisions.

They spent their time playing cards.

Hitler, who persistently under-rated the Russians, made the opposite mistake of over-rating the Western Allies.

Already, in the autumn of 1942, he feared an Allied invasion. The American, British, and Soviet secret services nurtured his fear by clever rumors about a second front. The skillfully launched specter of an invasion which was not to materialize for another twenty months was already tying down twenty-nine German divisions, including the magnificently equipped " Leibstandarte " and the 6th and 7th Panzer Divisions.

Twenty-nine divisions!

A quarter of them might have turned the tide on the Stalingrad-Caucasus front.

Einsatzbereit (ready for action), a Hon Sd.Kfz.10/4 halftrack carrier armed with a 2cm FlaK 30 stands by to fire on Soviet aircraft near the Volga. This weapon was being replaced by the improved FlaK 38, but the FlaK 30 remained in use through the war. The weapons were fed by 20-round magazines. Besides air defense their high explosive and armor-piercing rounds were effective against light armored and soft-skin vehicles, field fortifications, fortified buildings, and personnel.

Photo of northern portion of Stalingrad taken from a Stuka dive bomber.

An officer of 16. Panzer Division on 24 August observes enemy positions through a scissors periscope beside a Panzerdeckungslocher (armor protective trench) with a Unterschlupfe (dugout shelter). Landser referred to such trenches as a Panzergrab (armor grave). During the day the Division's Gruppe Drumpen launched an attack against Spartakovka, Stalingrad's northern most industrial suburb

The dawn 24 August attack on Spartakovka by Gruppe Drumpen was preceded by direct fire from 8.8cm guns and a heavy bombardment by Ju 87B bombers. Lines of Pz.Kpfw. llls are poised to go into attack once the fire is lifted.

During the Battle for Spartakovka a Soviet KV-1 heavy tank burns after a direct hit from antitank fire. Although 16 Panzer Division scored a number of successes, they had run into a solid defense in the northern outskirts of the city. Some of the counterattacking Soviet tanks had penetrated German lines as far as the command post of the 64. Panzergrenadier-Regiment.

To the German soldiers arriving along the banks of the Volga it seemed that victory was beckoning. In these photographs thousands of Soviet soldiers have been encircled, captured, and marched to hastily erected POW camps, mere barbed wire enclosures without any form of shelter or sanitary facilities. Little food and water was provided. The fate of these Red soldiers was sealed. Virtually all of them would be worked or starved to death. The female prisoner was a rarity. Contrary to popular myth there were no infantry units comprised of woman. Women served as signalers, medics,traffic controllers, administrative assistants. A small number served as snipers, a few ad hoc artillery units were formed, and some individuals served in tank units.

A Feldgendarmerie Unteroffizier at a make-shift POW camp in Krasnoarmeysk, guards Soviet prisoners, some of whom are women. The female officer holding her overcoat was a freely admitted commissar. At this time Soviet Commissars were no longer being executed unless it could be proven they had issued illegal orders (murder of POWs, use of explosive ammo, etc). Since Stalin, on 1 August 1941, had ordered the Commissars and Politruks to remove the star from the sleeve of their uniforms, it was no longer possible to tell the Commissars and Politruks from the enormous numbers of front-line prisoners. On 7 October 1941, therefore, the Army empowered the SD and Police to look for the Commissars and Politruks in the POW camps in the rear army zone. The segregation and execution commandos in these camps were dependent largely on informers. All persons identified were formally released from the POW camps and handed over to the SS. The number of the Soviet soldiers executed according to the Commando Order cannot even remotely be estimated. Claims that the numbers involved amounted to 580,000 to 600,000 men are nonsense. In May 1942, Hitler finally gave way to the urgings of the frontline troops and cancelled the Commissar Order in the area of operations. The “Special Treatment” of Commissars and Politruks in the prisoner of war camps was also stopped.

Soviet prisoners are collected beside an abandoned 45mm M1937 antitank gun. This and the very similar 45mm M 1932 were often pressed into German service as the 4.5cm Pak 184/1 (r) and 184(r), respectively. The German guards, probably rear area troops, are armed with the 7.9mm Mauser Kar98b carbine, a modernized Gew98 rifle from World War I. This lot of Soviets were found wandering around behind the lines near the town of Abganerovo, to the south of Stalingrad.

German aerial reconnaissance photograph shows the aftermath of the 24 August Luftwaffe raid on Stalingrad. The thick black smoke rises thousands of meters into the clear sky after some of the city's oil storage tank yard (Tanklager) on the Volga had been set aflame. The explosions scattered burning debris and fire to docks and jetties. These photographs also give an appreciation of the city's size; the extent of the outlying worker's housing areas, and the many gullies and ravines on the outskirts.

These Panzergrenadiere have reached the bluffs above the Volga. Their advance had been hampered by stiff resistance in the towns of Krasnoyarmeysk and Kuporsnoye where Red Army troops had dug in and fought a bitter and protracted battle of attrition. Panzergrenadiere had to be prepared to fight dismounted and distant from their vehicles just as other infantrymen.

An 8.8cm FlaK 36 pumps round after round into the northern outskirts of Stalingrad. German heavy artillery pound enemy positions on the outskirts of the city reducing it to burning rubble. The Acht-Achter was used for such direct-fire support and as an antitank weapon, but its high-velocity and long barrel made it ill suited for indirect fire, a role it was never used in.

Two members of a 7.92mm MG-34 open fire on suspected enemy targets on the outskirts of the city in early September. The machine gun is fitted with a Gurttrommel 34 (basket drum) containing a 50-round belt. A SchOtzengruppe (rifle group) was divided into a five to six-man SchOtzentrupp (rifle troop) under the assistant squad leader and a threeman Maschinengewehrtrupp (machine gun troop) plus the group leader, an Unteroffizier. Both wear Gummibander (rubber bands) cut from vehicle tire inner tubes on their helmets to secure camouflage materials.

Two Panzer inside a village on the outskirts of Stalingrad. The tank on the right with the tactical marking "523" is a Pz.Kpfw.III Ausf. J with a 5cm gun and on the left using a house as cover is a Pz.Kpfw. IV with a short 7.5cm gun, known as a Stumpf (Stumpy). Many tanks were stalled inside towns and villages that surrounded the Stalingrad. Soviet soldiers sniped at them with rifles and machine guns killing exposed crewmen and accompanying Panzergrenadiere and picked them off with 14.5mm antitank rifles, antitank hand grenades, hand-delivered demolition charges, captured German magnetic antitank hand mines, and Molotov cocktails.

A machine gunner smokes a pipe while overlooking the Volga from his Maschinengewehrloch (machine gun hole). This type of simple circular fighting position was also known as a Russisches Loch or Ruslock (Russian hole). He is armed with an MG-34 and a 9mm P-38 pistol (unseen) habitually carried in a holster on the left front of his Koppel (belt), but what the Landser called a Bauchbinde (bellyband).

A Schutzenloch fur Maschinegewehr (firing hole for a machine gun) was more commonly known to Landsers as a Maschinengewehrnest (machine gun nest). The optical sight of the MG-34 can be seen between the two helmeted crewmen. In German service the terms leichte (light) and schwere (heavy) Maschinengewehre defined the role and not the weight of the gun, as both roles were filled by the 7.92mm MG-34. Rifle groups had a light machine gun with a bipod and carried one or two spare barrels. A heavy machine gun group also had the bipod fitted machine gun, but additionally carried a heavy tripod, an optical sight, and additional spare barrels to provide long-range, sustained fire. The number of discarded ammunition cases attest that the two burning T-34s were accompanied by large numbers of of rifle troops, now mostly scattered in the wheat field, Ausradieren (Rubbed out- To wipe out or totally destroy a position, vehicle, or installation).

Pz.Kpfw.Ills halt to survey the broad steppe spread before them. The smoke from several brewed up Soviet tanks can be seen in the background. These tanks of 4. Panzer-Armee were south of Stalingrad in early September advancing to reach the city and reinforce the assault troops.

More Pz.Kpfw.Ills continue to advance south of the city, this time moving forward to engage Soviet units being attacked by dive-bombers. During this period the German offensive gained ground largely because the Luftwaffe supported the advance in relatively large groups and bombed the Soviets almost non-stop as they tried to counterattack.

Two Landser assist a walking wounded Kamerad, his shoulder bandaged with his Verbandspackchen (wound packets). With any "luck" this might be rated as a Heimatschuß — "homeland shot" (home wound), allowing him to be sent back to Germany for recovery.

WE'RE SAVED!

And the Battle of Stalingrad is about to be joined, the decisive battle in the European theater IMHO.

Thank you for all of these pings Homer.

I don’t often reply but i read each one.

Very interesting and informative.

Keep up the great work!

Thanks again :)

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.