Posted on 05/26/2011 5:25:29 AM PDT by Homer_J_Simpson

http://www.onwar.com/chrono/1941/may41/f26may41.htm

British aircraft damage Bismark

Monday, May 26, 1941 www.onwar.com

In the North Atlantic... A Catalina aircraft finds Bismark only 700 miles from Brest and it is clear that the aircraft of the Ark Royal (of Force H) offer the best chance of slowing the German ship so that she can be caught. The first strike launched by the Ark Royal finds and attacks the British cruiser Sheffield by mistake owing to bad weather. The attack fails because of defects in the magnetic exploders of the torpedoes, so simple contact types are substituted for a second strike. The 15 Swordfish find the correct target and score two hits. One hit wrecks the German battleship’s steering and practically brings her to a halt. During the night Bismark is further harried by torpedo and gunfire attacks by five British destroyers. It is unclear whether they score any torpedo hits.

In the Mediterranean... On Crete, the British commander, Freyberg, raises the question of a withdrawal from the island. During the night of the 26th most of the Allied forces withdraw from the Galatas position amid some confusion about the exact nature of their orders. Aircraft from the carrier Formidable attack the Stuka base at Scarpanto in the Italian Dodecanese. The carrier is hit twice by air attacks.

http://homepage.ntlworld.com/andrew.etherington/month/thismonth/26.htm

May 26th, 1941

UNITED KINGDOM:

Corvette FS Commandant d’Estienne d’Orves (ex-HMS Lotus) laid down.

Minesweeper HMS Eastbourne commissioned.

Corvette KNM Andenes (ex-HMS Acanthus) launched.

Gate vessels HMC GV 5 and CV 6 ordered. (Dave Shirlaw)

GREECE: CRETE: Carrier HMS Formidable, accompanied by HMS Barham and HMS Queen Elizabeth, flies off aircraft from a position well to the south for an attack on the Scarpanto Island airfields. In the counter-attack HMS Formidable and destroyer HMS Nubian are damaged, by Stukas flying from Scarpanto.

General Freyberg raises the question of evacuation from Crete. Withdrawal from their positions in Galetas will begin tonight.

British commandos under Brigadier Robert Laycock land at Suda Bay to cover the evacuation.

GOLD COAST: Night of 26/27 May 1941 U-69 (Jost Metzler) entered Takoradi travelling on the surface between the heavily fortified moles and laid seven mines. She escaped undetected. (Dave Shirlaw)

JAPAN: The Kayaba Ka-1, Army Model 1 Observation Autogyro makes its maiden flight.

In 1939, the Japanese Army purchased a Kellet KD-1A single-engine two-seat autogyro from the U.S. (The USAAC purchased nine KD-1s and designated them YG-1s.) Unfortunately for the Japanese, the machine was damaged beyond repair in a crash during flight tests at low altitude. The wreck was delivered to the Kayaba Industrial Co. Ltd.

(K.K. Kayaba Seisakusho) and they were told to develop a similar machine. A two-seat observation machine was built based on the KD-1A but modified to Japanese production standards. This machine makes its first flight today. About 240 Ka-1s were built. (Jack McKillop)

CANADA: Minesweeper HMCS Bayfield launched North Vancouver, British Columbia. (Dave Shirlaw)

U.S.A.: America’s first experimental blackout takes place at Newark, New Jersey.

Heavy cruiser USS Baltimore laid down.

Destroyer USS Doyle laid down. (Dave Shirlaw)

ATLANTIC OCEAN: After a 30 hour interval a Catalina flying boat of RAF Coastal Command 209 Squadron discovers the BISMARK about 700 nm from Brest, its port of destination. The Catalina was fitted with a recently improved ASV radar device.

The copilot on this Catalina was Ensign Leonard B. Smith, USNR. Another Catalina of RAF No 240 Squadron with Lieutenant James E. Johnson, USN, aboard begins shadowing the German ship. (Jack McKillop)

Later in the afternoon a Swordfish strike from Force H’s Ark Royal attacks the Sheffield in error. She is not hit. A second strike takes place in the evening by 810, 818 and 820 squadrons with 15 Swordfish led by Lt-Cdr Coode. They torpedo BISMARK twice and one hit damages her propellers and jams the rudders. As BISMARK circles, destroyers of the 4th Flotilla (Capt Vian) come up around midnight, and make a series of torpedo and gun attacks but with uncertain results.

HMSs Cossack, Maori, Sikh, Zulu and Polish Piorun have been detached from troop convoy WS8B, an indication of the seriousness of the BISMARK’s threat.

By this time Adm Tovey’s force of heavy ships has lost the Repulse to refuel, but been joined by HMS Rodney. They now come up from the west but do not attack just yet.

http://worldwar2daybyday.blogspot.com/

Day 634 May 26, 1941

In 30 hours since her last sighting by the British, German battleship Bismarck travels 750 miles Southeast towards France. At 10.30 AM, a Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boat piloted by British Flying Officer Dennis Briggs and US Navy ensign Tuck Smith (from Lough Erne, Northern Ireland) locates Bismarck 700 miles West of Land’s End, England. British Admiral Tovey orders Royal Navy ships to the area, including Force H from Gibraltar with aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal. At 4 PM, 15 Swordfish launch from Ark Royal but attack British cruiser HMS Sheffield in error (no damage done) and return to Ark Royal to reload torpedoes. At 8.55 PM, the Swordfish attack Bismarck and return to Ark Royal safely. 1 torpedo hits the armour belt causing little damage but the other jams her rudder hard to port, causing Bismarck to steam in circles. Tovey sends 6 destroyers to harry Bismarck and maintain contact overnight while the capital ships converge.

http://www.kbismarck.com/histoperi.html

26 May 1941 (Monday):

1030. Sighted by Catalina Z/209 flying boat at about 49º 20’ North, 21º 50’ West.

1740. Sighted by Sheffield.

2047-2115. Attacked by fifteen Swordfish of the 810th, 818th, and 820th Squadrons from carrier Ark Royal. The Bismarck is hit by two (or three) 18 inch MK XII torpedoes. One torpedo (or two) hits the port side amidships, and another hits the stern in the starboard side. As a result of this attack both rudders jammed at 12º to port.

2054. Bismarck reports to Group West: “Attack by carrier-borne aircraft!”

2105. Bismarck reports to Group West: “[Position] Square BE 6192. Have sustained torpedo hit aft.”

2115. Bismarck reports to Group West: “Torpedo hit amidships!”

2115. Bismarck reports to Group West: “Ship no longer manoeuvrable!”

2130-2155. Fires six salvoes against the Sheffield. Distance nine miles. No hits scored.

2140. Bismarck reports to Supreme Command of the Navy (O.K.M.) and Group West: “Ship unable to manoeuvre. We will fight to the last shell. Long live the Führer.”

2238. Sighted by Polish destroyer Piorun.

2242. Opens fire against Piorun.

2325. Bismarck reports to Group West: “Am surrounded by Renown and light forces.”

2358. Bismarck reports: “To the Führer of the German Reich, Adolf Hitler: We shall fight to the last man with confidence in you, my Führer, and with rock-solid trust in Germany’s victory!”

2359. Bismarck reports to Group West: “Ship is weaponry-wise and mechanically fully intact; however, it cannot be steered with the engines.”

http://www.kbismarck.com/bismarck-chase.html

The Bismarck is Located.

In the morning of 26 May, as the Bismarck was approaching the French coast, the crew was ordered to repaint the top of the main and secondary turrets yellow. Hard job considering the state of the seas, nevertheless it was carried out although the yellow paint washed off at least once.

A few hours earlier, at 0300, two Coastal Command Catalina flying boats had taken off from Lough Erne in Northern Ireland on a reconnaissance mission in search for the Bismarck. At about 1010, Catalina Z of 209 Squadron commanded by Dennis Briggs sighted the German battleship that immediately answered with very accurate anti-aircraft fire.2 The Catalina jettisoned her four depth charges and took evasive action after her hull was holed by shrapnel. Then reported: “One battleship, bearing 240º, distance 5 miles, course 150º. My position 49º 33’ North, 21º 47’ West. Time of transmission 1030/26.” After more than 31 hours since the contact was broken, the Bismarck had been located again. Unfortunately for the British, however, Admiral Tovey’s ships were too far away from the German battleship. The King George V was 135 miles to the north, and the Rodney (with a top speed of 21 knots) was 125 miles to the northeast. They would never catch up with the Bismarck unless her speed could be seriously reduced.

Only the Force H, under the command of Vice-Admiral Sir James F. Somerville, sailing from Gibraltar, had a chance to intercept Bismarck. The battlecruiser Renown (Captain Rhoderick R. McGriggor) was in the best position, but having lost the Hood only two days earlier, the Admiralty did not permit Renown to engage the Bismarck. The best hope for the British was to launch an air strike from the carrier Ark Royal. The Ark Royal had already launched 10 Swordfish at 0835 to try find the Bismarck, and once the report of the Catalina sighting arrived, the two closest Swordfish altered course to intercept. At 1114, Swordfish 2H located the German battleship too, followed seven minutes later by the 2F. Shortly afterwards two more Swordfish, fitted with long-range tanks, were launched to relieve 2H and 2F and keep touch with Bismarck.

At 1450, fifteen Swordfish commanded by Lieutenant-Commander J. A. Stewart-Moore took off from the Ark Royal (Captain Loben E. Maund) to attack the Bismarck. At 1550, they obtained radar contact with a ship and dived to attack. The attack, however, turned out to be a failure since the ship sighted was actually the light cruiser Sheffield (Captain Charles A. Larcom) which had been detached from Force H to make contact with the Bismarck. Luckily for the British, the Sheffield was not hit by any of the 11 torpedoes launched because they had faulty magnetic pistols. Two torpedoes exploded upon hitting the water, three on crossing the cruiser wake, and the other six were successfully avoided. The Swordfish returned to the Ark Royal where they landed after 1700, but not without trouble because of the terrible weather conditions. The rise and fall of the stern was measured to be 56 feet, and three aircraft smashed their undercarriages against the flight deck. Shortly afterwards, at 1740, the Sheffield obtained visual contact with the Bismarck.

The British put every effort on one last attack. It would be dark soon, and they knew this was their last real chance to stop or at least slow down the Bismarck. If they failed again, the Bismarck would reach the French coast on the next day, since another air strike late at night was unlikely to succeed. Therefore, at 1915, another group comprised of fifteen Swordfish, mostly the same used in the previous attack, took off from the Ark Royal, and this time their torpedoes were armed with contact pistols.

Meanwhile, the pursuing British forces had run across U-556 (Lieutenant Herbert Wohlfarth) which sighted the Renown and the Ark Royal at 1948. The German submarine was perfectly placed for an attack, but could not do so as it had no torpedoes left. Wohlfarth had spent his last “fishes” on the ships of convoy HX-126 a few days back. Therefore, U-556 could only make signals reporting the position, course and speed of the enemy.

The Swordfish striking force, this time under the command of Lieutenant-Commander T.P. Coode, first approached the Sheffield to get the range and bearing to the Bismarck, and at 2047, began the attack. Bismarck’s anti-aircraft battery opened fire immediately. During the course of the attack, the Bismarck received at least two torpedo hits. One torpedo (or two) hit the port side amidships, and another struck the stern in the starboard side. The first hit did not cause important damage, but the second jammed both rudders at 12º to port. The Bismarck made a circle and then began to steer northwest involuntarily into the wind. As before, none of the Swordfish were shot down although some were hit several times. The damage to the Bismarck was so serious that at 2140, Admiral Lütjens sent the following message to Group West: “Ship unable to manoeuvre. We will fight to the last shell. Long live the Führer”.

The impact in the stern area caused the flooding of the steering and other adjacent compartments. This meant that all repair attempts would have to be done under water. Divers were ordered to enter the steering compartment in order to free the rudders, but the violent movement of the water inside made this an impossible task. It was not possible to lower divers over the side due to the high seas. As an alternative, it was considered to blow the rudders away with explosives and try to steer the ship using the propellers alone, but the idea was rejected fearing that the explosion could damage the propellers.

Destroyers Attack Bismarck.

After the aerial torpedo attack, the new erratic course of the Bismarck caused her to close the range with the Sheffield. At about 2145, Bismarck opened fire on the Sheffield at a range of about nine miles. Bismarck fired a total of six salvoes and the British cruiser turned away to the north under the cover of a smoke screen. The Sheffield was not hit, but some splinters disabled her radar and injured twelve men of whom three died later.3 The turn caused Sheffield to lose contact with Bismarck, but at 2200, she made contact with the destroyers of the 4th Flotilla (Captain Philip L. Vian) Cossack, Maori, Zulu, Sikh and Piorun, and provided them with the approximate bearing and distance to the German battleship.

At 2238, the Polish destroyer Piorun (Commander Eugeniusz Plawski) sighted the Bismarck. The German battleship responded shortly thereafter with three salvoes. The destroyers proceeded to attack, but Bismarck defended herself vigorously in the dark. At 2342, splinters knocked down Cossack’s antennas.

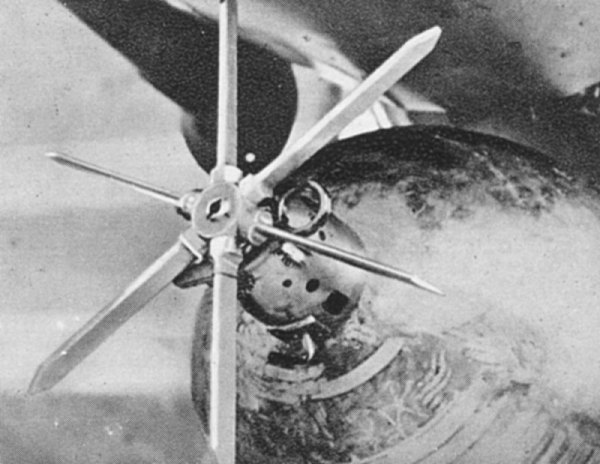

An 18 inch MK XII torpedo like those used by the Swordfish against the battleship Bismarck. The contact pistol is fitted and when the point of one of the "whiskers" strikes the enemy hull, the detonator is fired and the warhead explodes.

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1191813/Pilot-sank-Bismarck-tells-tale-70-years.html

‘I sank the Bismarck but only found out 59 years later’: British pilot learns of his place in history

By Daily Mail Reporter

Every war veteran has a story to tell. But few could rival John Moffat’s extraordinary tale.

Now 89, Mr Moffat had a ringside seat to the sinking of the Bismarck, one of the most dramatic sea battles of the Second World War.

But it was relatively recently that the pilot, who gave up flying only last year, found out just how pivotal his role was.

It was the torpedo he fired that crippled the rudder of the German battleship, leaving it at the mercy of Royal Navy ships which then sank it in the Atlantic off the west coast of France on May 27, 1941.

He was piloting one of three Swordfish open-cockpit biplanes that set off from the aircraft carrier Ark Royal to take vengeance on the Bismarck, which days before had destroyed the British warship Hood with the loss of 1,416 lives.

‘What nobody talks about were the conditions - they were unbelievable,’ recalled Mr Moffat, who has written a book, I Sank The Bismarck, about his experiences.

‘The ship was pitching 60ft, water was running over the decks and the wind was blowing at 70 or 80mph.

Bismarck

‘And nobody mentions the deck hands who had to bring the planes up from the hangars - they did something special. After they brought them up they had to open

the wings which took ten men for each wing. And then they had to wind a handle to get the starters working.

‘I only stopped flying nine months ago and there are no other planes in the world that could have done what the Swordfish planes did that day.

‘After take-off we climbed to 6,000 feet to get above the really thick cloud and we knew when we were near because all hell broke loose with Bismarck’s fire. We got the order to attack and I went down and saw the enormous bloody ship. I thought the Ark Royal was big, but this one, blimey.

‘I must have been under 2,000 yards when I was about to launch the torpedo at the bow, but as I was about to press the button I heard in my ear “not now, not now”.

‘I turned round and saw the navigator leaning right out of the plane with his backside in the air. Then I realised what he was doing - he was looking at the sea because if I had let the torpedo go and it had hit a wave it could have gone anywhere. I had to put it in a trough.

‘Then I heard him say “let it go” and I pressed the button. Then I heard him say “we’ve got a runner” - and I got out of there.

‘My navigator was a chap called John “Dusty” Miller and I’ve spent the last 20 years trying to find out what happened to him or where he is.’

Mr Moffat pulled up before the torpedo hit and didn’t see it strike. The following morning he flew to the ship for a second attack but there was no need.

He watched as the Bismarck, which had been under siege from the Royal Navy, rolled over. And he saw hundreds of German sailors leaping into the water as she started to sink. Only 115 of Bismarck’s crew of 2,222 survived.

‘I didn’t dare look any further, I just got back to the Ark Royal and I thought: “There but for the grace of God go I”,’ said Mr Moffat, who now lives in Dunkeld, Scotland.

He only found out it was his torpedo that crippled the Bismarck when the Fleet Air Arm - the Navy’s air force - wrote to him in 2000. He said: ‘It gave me a sort of satisfaction.’

I believe one of the pilots on the Catalina was an American officer. So much for neutrality.

http://www.navytimes.com/legacy/new/0-NAVYPAPER-1642064.php

April 10, 2006

Lt. helped sink Bismarck before U.S. entered WWII

Tuck Smith was in Britain training RAF pilots

By Robert F. Dorr and Fred L. Borch

Special to the Times

Leonard B. “Tuck” Smith, a Navy lieutenant on loan to Great Britain as part of the lend-lease program, may have been the first American to participate in a World War II Allied naval victory.

In May 1941, six months before the U.S. entered the war, Smith was on air patrol near Ireland when he spotted the German pocket battleship Bismarck. His radio message to the British enabled them to locate the famous and much-vaunted Bismarck.

Born in Missouri in 1915, Smith spent his boyhood on a farm until entering flight training with the Navy in 1938. He became a pilot on the PBY-5A Catalina, a flying boat designed for reconnaissance and anti-submarine duty.

After President Roosevelt decided to lend a number of Catalinas to the British through lend-lease, then-Lt. j.g. Smith was sent to Britain to train Royal Air Force pilots.

Smith accompanied the pilots on routine patrols. This explains why he was part of the May 1941 hunt for the Bismarck.

The German warship sunk the battle cruiser Hood, the pride of the British Navy, on May 24. This was a disaster for the British, as only three sailors in the Hood’s crew of 1,418 survived.

After the Bismarck eluded the British ships pursuing it and headed for the open sea, the British mounted a frantic search. Radar was in its infancy, so the only way to locate an enemy was to see him.

About 10:30 a.m., on May 26, 1941, Smith was in a Catalina along with a Royal Air Force pilot and crew. They were flying at an altitude of about 500 feet when Smith looked down through the fog and saw the German heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen. As Smith flew closer, the Bismarck, so far unseen, fired on the plane.

The American and his RAF comrades took shrapnel hits on their aircraft.

“First there was great excitement. We were sent out to look for it, and there it is,” Smith told an interviewer in Ireland in 1992. “But a few minutes later, they [the Bismarck] were shooting at us. Then you have feelings of holy terror.”

Despite a continuing barrage of flak, Smith and the Catalina stayed aloft over the much more powerful Bismarck and began radioing contact reports to the nearest Royal Navy and RAF units. Smith stayed in the air for another five hours, directing air and surface forces to a position from which they attacked and then sank the German battleship May 27.

For his actions, Smith received the Distinguished Flying Cross. Since the U.S. was officially neutral, it was a risky decision to recognize Smith for his participation in a combat operation. Yet, a citation signed by Navy Secretary Frank Knox lauded Smith’s “heroism and extraordinary achievement as a volunteer observer during an aerial search for the German pocket-battleship Bismarck.”

As Smith’s son, Bruce, a retired lieutenant colonel in the Air Force Reserve, explained: “Dad is proud of the small role he played in the naval history of World War II, a unique role for an American because the war hadn’t started for us yet.”

Smith retired as a captain in 1962. He now lives on San Juan Island, Wash.

Robert F. Dorr, an Air Force veteran, lives in Oakton, Va. He is the author of “Chopper,” a history of helicopter pilots. His e-mail address is robert.f.dorr@cox.net. Fred L. Borch retired from the Army after 25 years and works in the federal court system. He is the author of “Kimmel, Short and Pearl Harbor,” an analysis of the December 1941 attack on Hawaii. His e-mail address is borchfj@aol.com.

Let's just call that a practice run.

But wait a minute - If the Swordfish pilots hadn't exerienced this incredible snafu would they not have had the same results when they really did attack Bismarck? Which would have left Bismarck steaming straight for France and safety as night fell?

http://www.world-war.co.uk/Southampton/sheffield.php3

HMS Sheffield

Town Class Light Cruiser

Several good photos here.

How about this twist of fate?

http://www.bismarck-class.dk/bismarck/miscellaneous/special_bond/specialbond.html

On 26 May, when dispositons were being made to support the Bismarck in her increasingly critical situation, new instructions were sent to the U-boats in the Bay of Biscay. One of those boats was the U-556, whose commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander Herbert Wohlfahrt, was ordered to reconnoiter and operate in the area of the Bismarck’s most recently reported position. When Wohlfart received those orders, he was on his way home from a patrol that began on 1 May. Therefore, he was low on fuel and, on his way to the Bismarck, he would have to be extremely economical with what he had left. Furthermore, he had expended all his torpedoes against British convoys.

Wohlfahrt reached the immediate area around the Bismarck on the evening of 26 May. Around 1950 he saw the Renown and the Ark Royal coming out of the mist at high speed the big ships of Force H. Nothing for it but to submerge. “Enemy bows on, 10 degrees to starboard, without destroyers, without zigzagging,” as Wohlfahrt later described it. He would not even have had to run to launch torpedoes. All he would have had to do was position himself between the Renown and the Ark Royal and fire, at both allmost simultaneously. If only he had some torpedoes! He had seen activity on the carrier’s (Ark Royal’s) flight deck. Perhaps he could have helped the Bismarck. That is what he thought at the time. But what he saw was the activity after the launching of the second and decisive attack on the Bismarck. So, even if he had torpedoes, he would not have been able to save the Bismarck from the rudder hit. The Swordfish had long since banked over the Sheffield and were just about to attack the Bismarck.

Fifty minutes later, at 2039, Wohlfahrt surfaced and made a radio report: “Enemy in view, a battleship, an aircraft carrier, course 115°, enemy is proceeding at high speed. Position 48° 20’ north, 16° 20’ west.” Wohlfahrt intended his report to be picked up by any of his comrades who might be in the vicinity and able to maneuver to attack. Then he proceeded on the surface at full speed behind the Renown and the Ark Royal. Their course to the Bismarck coincided almost exactly with his own. Every now and again, he submerged and took sound bearings to both ships, but after 2200 he could no longer hear them. The race between his little boat and the two big ships was an unequal contest.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.