Skip to comments.

Book Review: In Living Color: Matisse the Master

by Hilary Spurling

Commentary ^

| 12/03/05

| Steven C. Munson

Posted on 12/06/2005 3:30:56 AM PST by Republicanprofessor

In this second volume of her biography of arguably the greatest of 20th-century painters, Hilary Spurling recounts the life of Henri Matisse from 1909, when he was in the midst of consolidating the gains of his breakthrough Fauve period, through the two world wars, to his death in his studio at Cimiez in 1954. As with her earlier volume, The Unknown Matisse this new book gives us a down-to-earth portrait of the artist and his family while faithfully rendering a bygone era in which both art and those who made it, theorized about it, and bought it were taken seriously.

In Matisse’s case, most of those who took him seriously were foreigners; French critics and art lovers tended to be dismissive, if not downright hostile. One of the striking aspects of Spurling’s story is the recurring role of foreign supporters, and of foreign influences, in the painter’s career and artistic development. Among his key American collectors, for example, were Albert Barnes, who commissioned a huge mural—Dance (1933)—for his foundation outside Philadelphia, and the Cone sisters, Eta and Claribel, whose collection of Matisses is now in the Baltimore Museum of Art. Another American supporter was the painter and critic Walter Pach, who helped organize the sensational Armory Show in New York City in 1912 that introduced modern art to the American public.

Then there was Matthew Prichard, an English philosopher and academic outsider who, mystified at first by Matisse’s revolutionary paintings, not long afterward became one of his most ardent champions. It was Prichard who took Matisse to an exhibition of Islamic art in Munich, a show that led the painter to spend time in southern Spain studying Islamic architecture and the patterned designs that would so profoundly influence his work. He would be introduced to still another influence—that of Russian religious icons—by the collector Sergei Shchukin, who organized a visit to Moscow that elevated Matisse to the unaccustomed status of cultural celebrity.

Another Russian, the refugee Lydia Delectorskaya, would become indispensable to Matisse throughout the last two decades of his life—especially the years in which he created his famous painted paper cutouts—serving first as housekeeper, and later as business manager, companion, and model. As a model she proved an inspiration, helping him to break out of what had amounted to a six-year painter’s block in the mid-1930’s. One observer left a revealing description of the artist and his muse at work:

His incredible stress in the moment before starting his little pen sketches. Lydia told him: “Come on now, don’t let yourself get so upset.” His violent response: “I’m not upset. It’s nerves.” The atmosphere of an operating theater. . . . And Matisse drawing without a word, without the slightest sign of agitation but, within this immobility, an extreme tension.

Much of the remarkable first-person detail accumulated by Spurling is a result of her having been given unique access to the Matisse Archive in Paris. Since Matisse, his daughter Marguerite, and his youngest son Pierre were all fairly prolific correspondents, their letters provide a treasure trove of information about the family’s movements, thoughts, and feelings. The sense of intimacy Spurling creates is beguiling (if at times a little overwhelming), and her immersion in the records of Matisse’s daily life has enabled her to produce an insightful study of his character and personality, as well as of the enormous demands these imposed on both himself and his family.

Above all, perhaps, on Amélie, his wife. Indeed, the story Spurling tells in this book is in some ultimate sense the story of a marriage—a highly successful partnership dedicated to Henri’s work that ended, some 40 years after it began, in a bitter and irreparable separation. Spurling’s depiction of the rise and fall of Matisse’s marriage, and of his changing relations with his three children, brings home an essential point: for all of his achievements as an artist, including worldwide fame and financial success, and for all of his family’s dedication to him and involvement in his work, he and they were in many respects really quite ordinary, no better or worse than other people at dealing with the vicissitudes of life.

As they grew older, Matisse’s children acquired the values—a commitment to painting and to the independence of mind and spirit that this entailed—of their parents. They became tough critics, telling their father frankly what they thought of his work, especially when in their view it failed to live up to his previous standards. According to Spurling, these responses, which Matisse regarded more seriously than anybody else’s, often spurred him on when he was groping for a new direction. But his relations with his family were complicated and often difficult. He was generous in providing support and encouragement to all kinds of people—artists, students, friends, and models. At home, in his relations with his wife and children, he was often affectionate and concerned; but he could also be peremptory, dictatorial, overbearing, and unwittingly unkind. As Spurling reports: “His wife said that, for all his good intentions, her husband had no idea when to stop.”

This aspect of his personality also caused him trouble in his work. Spurling writes that “Matisse lamented the lack of natural facility that had made his entire career a relentless uphill struggle.” And as Françoise Gilot put it, contrasting him in this regard with Pablo Picasso, “he was interested neither in fending off opposition, nor in competing for the favor of wayward friends. His only competition was with himself.” The toll this took became acutely apparent in 1910, when, after completing two very large and stunningly colorful paintings, Dance (II) and Music (both commissioned by Sergei Shchukin), he suffered a physical and emotional breakdown.

He described his own activity of painting as requiring “a state of emotion, a sort of flirtation which ends by turning into a rape. Whose rape? A rape of myself, of a certain tenderness or weakening in face of a sympathetic object” (namely, the model). An intensity of feeling, of one kind or another but usually involving sensations of unencumbered pleasure, is indeed manifest in Matisse’s work—especially in his paintings and drawings but also in his sculptures (which are often quite brutal in form). But what is not manifest is sentimentality, any traces of which he was ruthless in extinguishing from his art.

What Matisse recognized, and taught others to recognize, was the critical importance for a modern painter of finding a mode and means of artistic expression that would enable him to be true to his own sensibility and experience. In his case, this entailed responding to what might be called the sensuous aspects of the sublime—whether in the qualities of Mediterranean light, the arrangement of a still life, the pose of a model, the great art of the past, or the expressive power of color itself.

The means he developed to achieve the goal of transposing his feelings onto canvas were radical—and liberating. These included, in the summary of one critic, “flatter patterning, drawing simplified to the contours of a silhouette, larger areas and heavier saturations of unbroken color, the pictorial image more and more reduced to a single plane.” His friend Maurice Sembat described encountering an example of Matisse’s revolutionary approach in Seated Nude in 1909:

We had come across a strange little canvas, something gripping, unheard of, frighteningly new: something that very nearly frightened its maker himself. On a harsh pink ground, flaming against dark blue shadows reminiscent of Chinese or Japanese masters, was the seated figure of a violet-colored woman. We stared at her, stupefied, astounded, all four of us, for the master himself seemed as unfamiliar as any of us with his own creation.

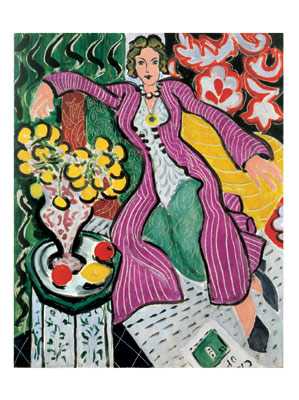

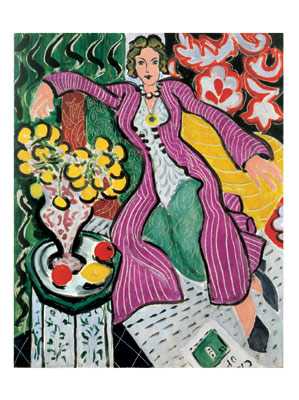

“You see, I wasn’t just trying to paint a woman,” Spurling quotes Matisse’s explanation, “I wanted to paint my overall impression of the south.” One can see, and feel, the variously evocative results of this aesthetic in such masterpieces as Still Life with Blue Tablecloth (1909), Decorative Figure on an Ornamental Ground (1925-26), and Interior: Flowers and Parakeets (1924); all three were recently on view in New York’s Metropolitan Museum exhibition, Matisse: The Fabric of Dreams, His Art and His Textiles. One can also see Matisse’s genius at work in The Blue Window(1913) and The Red Studio (1911), both at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and Studio, Quai Saint-Michel (1916-17) at the Phillips Collection in Washington. (The latter is far more traditional than the former two in its representation of space and light, yet no less modern a picture.)

Just as he did in managing his inner demons, Matisse relied on his own stoical and determined character in dealing with the often fierce criticism his work evoked from critics and the French public alike. He felt—it is hard to say how often—misunderstood; but then, as Spurling points out, his aesthetic breakthroughs often unnerved Matisse himself. Still, he knew that he had always to keep pushing the boundary, with results that amazed even his greatest contemporaries, Picasso and Pierre Bonnard. “Matisse is a magician,” said the former when he saw Still Life with a Magnolia (1941), “his colors are uncanny.” And the latter, referring to Matisse’s use of broad flat areas of color, asked, “How can you just put them down like that, and make them stick?”

In her preface, Spurling writes that one of her purposes in this biography has been to refute several myths about the painter’s personal life that over the decades proved damaging to his reputation. One is the notion that, during World War II, “he had dealings with the Nazi regime in France.” Spurling’s account of the ordeals experienced by Matisse and his family from 1939 to 1945—and their courageous response—makes it clear that any such charge of collaboration is baseless.

Another persistent and popular idea has been that Matisse regularly slept with his models, enjoying an “exploitative” relationship with them. In Spurling’s view, this assumption unfortunately colored the responses to the work Matisse produced in Nice in the 1920’s and 30’s, in particular his well-known paintings of women seated in hotel interiors and the sultry nudes—odalisques—decked out in oriental costume against richly patterned backgrounds. These were viewed by many contemporaries as lightweight and frivolous, and by others as evidence of a reactionary backsliding from Matisse’s earlier revolutionary experiments. In answering this charge of self-indulgence, Spurling makes a persuasive case that Matisse’s relations with his models were in fact quite chaste, pointing out, as he himself did, that he expressed his erotic feelings on canvas.

Spurling’s intention in raising this issue is in part to reemphasize the aesthetic significance of certain of Matisse’s works, both in themselves and in terms of his later development. But here and elsewhere she is primarily writing as a biographer, not as an art historian, and her focus is mainly on the man rather than on his oeuvre. While that is as it should be, at times Spurling gets so caught up in the ebb and flow of her subject’s moods, particularly his self-doubts, that one almost forgets that, during the years in question, Matisse was becoming a big success.

What that success may have meant to him is something that is not fully explicated. At one point, Matisse said to his daughter that he wanted to leave something behind; at another, that he did not want to be forgotten. Spurling reports he asked Picasso, “What do you think they have incorporated from us?,” referring to the work of the American abstract painters Jackson Pollock and Robert Motherwell. “And in a generation of two, who among the painters will still carry a part of us in his heart, as we do Manet and Cezanne?”

Such statements, expressions of a desire for some kind of immortality, are common enough; in this sense, too,Matisse was an ordinary man. His art, however, was anything but that. Although he did not live to know it, he was, and is, carried today in the hearts of artists—the late Richard Diebenkorn, among others, comes to mind—whose work he might very well have been pleased to see. The triumph of Hilary Spurling’s masterful biography is that she conveys both the ordinary and the truly extraordinary in the life of this towering artist.

TOPICS: Arts/Photography; Education

KEYWORDS: art; inlivingcolor; matisse

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first 1-20, 21-23 next last

A fascinating review of what looks to be a wonderful book on Matisse.

To: Republicanprofessor

Images:

Barnes Collection with Matisse's Dance in upper left

Decorative figure on an Ornamental Ground

Unfortunately, I have to post and run, so I'll let others post what images they want and discuss Matisse. I thought the insights to his marriage and the influence of his children upon his work was intriguing.

To: Sam Cree; Liz; Joe 6-pack; woofie; vannrox; giotto; iceskater; Conspiracy Guy; Dolphy; ...

Art Ping list.

Let Sam Cree or me know if you want on or off this ping list.

To: Sam Cree; Liz; Joe 6-pack; woofie; vannrox; giotto; iceskater; Conspiracy Guy; Dolphy; ...

Art Appreciation/Education ping.

Let me know if you want on or off this list.

To: Republicanprofessor

Do you have a picture of the "violet-coloured woman"?

Leni

5

posted on

12/06/2005 3:42:23 AM PST

by

MinuteGal

To: Republicanprofessor

"What Matisse recognized, and taught others to recognize, was the critical importance for a modern painter of finding a mode and means of artistic expression that would enable him to be true to his own sensibility and experience." I'm wondering if that isn't another way of saying that a modern painter must hit upon a lucky accident of style that can be repeated?

6

posted on

12/06/2005 3:53:01 AM PST

by

Sam Cree

(absolute reality) - "Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one." Albert Einstein)

To: Sam Cree

That being said, there is a copy of Elderfield's tome on Matisse in my library, searching through it, I do find a couple things to like. I believe his dancers are universally liked. OTOH, can't figure out how that book got there!

7

posted on

12/06/2005 4:25:18 AM PST

by

Sam Cree

(absolute reality) - "Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one." Albert Einstein)

To: Sam Cree

a modern painter must hit upon a lucky accident of style that can be repeated? Believe it or not, it takes a great deal of work and intuitive knowledge to develop a unique style of abstraction. So many people settle for a slight variation of what has gone before. Matisse may have been able to be more unique as he was one of the first to delve into abstraction. So it is doubly hard for us following him to be more unique.

To: MinuteGal

Do you have a picture of the "violet-coloured woman"? Leni,

I just changed violet to purple for a google image search, and this is what turned up. I don't know the work off-hand, and I don't know if this is what they referred to in the article. But it has his great balance of lively shapes and color that usually conveys deep contentment if not outright happiness.

What I also appreciate about his work is his appreciation of daily details, which are enhanced in his paintings. We thus see his regard for things that we may overlook in our headlong twenty-first century rush to get things done.

To: Republicanprofessor

Oh, my....if you posted a picture, nothing showed up but the name of the hosting service. Don't worry about it, I'll do a search. Thanks mucho,

Leni

To: MinuteGal

I try again. [I hate it when it does that (and when I'm in too much of a hurry to check).]

To: Republicanprofessor

Excellent, my dear Professor. I just HAD to see what was in that painting that "stupified" and "astounded" some people so much.

Matisse used a lot of colors in this piece which we might consider "clashing", but he pulled it off brilliantly. The composition is perfect. I love it.

Thanks so much for always going the extra mile for us art lovers.

Leni

To: Republicanprofessor

I don't know, it might take even more work and intuitiveness to appreciate abstract work!

I'm partially kidding here, I for one think that the art world is absolutely enriched and enhanced by the presence of abstract work. It makes it an altogether more interesting and free place. Sad would be the day when all art had to be kept within tight borders of any kind.

But as always, even though I like abstract work, I sometimes wonder how the term "greatness" gets attached to some of these folk - Matisse for instance. Not for his line work or use of color, I don't think. And that the art world thinks him great seems more of an offhand compliment. Anyhow, I do actually like his stuff well enough.

'Course, I am always the first to admit that the standards that really determine the greatness of art are also the most elusive to pin down. The abstract ones.

Seriesly though, while all artists build on what others did before, if it was any good, everyone's work will automatically be original, as long as they aren't consciously copying the style of someone else. I don't think the possession of skill should disqualify one from producing "good art."

13

posted on

12/06/2005 6:04:55 PM PST

by

Sam Cree

(absolute reality) - "Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one." Albert Einstein)

To: Sam Cree

Sam, I want to push you to post some Matisse images that you like and those you don't and tell me

why you feel this way. Sometimes he has messy sections in his paintings that I would have smoothed out, and yet I think those very sections give his paintings that modern sense of a work in progress. (Also evident in works from van Gogh to Henry Moore's sculpture to Pollock, but we've already been to Pollock's work in earlier posts.)

I'll go first with ones I think are strong and not as strong.

This Harmony in Red from about 1911 shows the quintessential reduction of line and color to emphasize the quiet, daily pleasures and rhythms of life. Would that I had more time to arrange fresh flowers and fruit on my tables!

These are only two examples of works that Matisse reworked until the forms, colors and rhythms were right. I do think the figures are a bit awkward in the left one (but isn't our life filled with awkward moments and poses?). I saw that left one at the recent MOMA Picasso/Matisse show (in the Brooklyn temporary warehouse museum) and the blue-green color in the lower body blew me away. One gains so much by seeing the works in person with the real size, color and impact the artist intended.

Of course, when you work in the studio every day, some works are bound to be less good than others. Picasso sure had a great deal of less attractive works, such as Weeping Woman below.

.jpg)

I think Picasso here is relying on his skill and style in a more superficial level. He is just whipping out works that will sell, the same way that some realists repeat their successful styles again and again for easy sales. In both cases, they don't go below the surface for a deeper truth.

I agree that both abstraction and realism, and all kinds of works in between, liven the art world today. But the best artists dive deeper to really explore new forms and content and are not satisfied with what has gone before. It is often harder to understand these works, so they are not readily accepted.

To: Republicanprofessor

I like the above as well as any Matisse paintings. The colors actually work well, and the dancers seem both primitive and happy, the nudity is a pleasant aspect as well in this case. Anyhow, the figures are wonderfully alive and in motion. Plus, it's very decorative, looked good on a shopping bag I once saw. Otherwise I have seen a couple female faces from Matisse that I found attractive, they managed to catch something of the ever fascinating female expression. They caught a little bit of truth, in other words.

But I think maybe the important aspect of what we are discussing here is the self expression in art. IMO, all great artists have gone for that, whether their work was representational or purely abstract. Even in realism, it's not the accuracy of representation that carries the day, but the truth captured by the artist, and what he gives of himself to the work. So I think great (fine) art must both capture a truth of one kind or another and must show us a little bit of the soul of the artist.

Great commercial art, or illustration art, does the same thing, plus serves the purpose to which it is assigned. I haven't looked in "Communication Arts" magazine in quite a while, but there is usually some really eye opening stuff in that publication.

"But the best artists dive deeper to really explore new forms and content and are not satisfied with what has gone before. It is often harder to understand these works, so they are not readily accepted."

RP, I don't really think any of the great representational artists have ever thought they were not treading new ground. I don't think one must do abstract to blaze a new trail. Of course not everyone is really interested in blazing new trails, whether they be abstract or realists. One thing about new trails, they are kind of like finding new fishing holes, not easy to do. But playing someone else's game rarely works well either, an imitation is always just that. Master what skills may be appropriate, but it's best to be oneself.

These kinds of discussion always bring to my mind the question posed by Jacques Barzun (I have his book by my bed, it keeps putting me to sleep, though), if the art of the old masters was realism, how come it all looks so different? I think one of the ironies of "realism" is that the more abstract you can make it, the more "realistic" it gets.

Apologies if all this seems obvious and shallow. I'm having fun figuring it out, though.

15

posted on

12/07/2005 1:21:40 PM PST

by

Sam Cree

(absolute reality) - "Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one." Albert Einstein)

To: Republicanprofessor

16

posted on

12/07/2005 5:40:42 PM PST

by

Samwise

(I freep; therefore, I am.)

To: Sam Cree

I don't really think any of the great representational artists have ever thought they were not treading new ground. I don't think one must do abstract to blaze a new trail.I didn't mean to imply that only abstract artists braved new form and content. Art history is full of great names who are realists: from Piero della Francesca to Michelangelo to Caravaggio, Rembrandt and Monet. In the twentieth century, Alice Neel bucked the abstract expressionist trend and just persevered in her own kind of expressionist portraits (that were pretty realistic compared to Pollock and his colleagues).

Alice Neel of Andy Warhol and her daughter-in-law in the last week of pregnancy (with husband in the background) and then with daughter Olivia.

To: Republicanprofessor

How well do you like Lucien Freud's work, RP? I admire it for the technical virtuosity and the feeling, but confess that I don't really like it.

18

posted on

12/07/2005 9:28:58 PM PST

by

Sam Cree

(absolute reality) - "Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one." Albert Einstein)

To: Sam Cree

I basicially agree: he is very skilled. But as a woman, I am offended by how he treats women as objects. I also find his work self-indulgent and needlessly shocking, perhaps purposely politically so. Does that really look like Reagan? What an unflattering and uncentered image! If anything, Reagan knew who he was and what he was doing.

But he is conveying what he wants to convey, in a strong, personal style, which means that he is a strong artist, whether you and I agree or like his work or not.

To: Republicanprofessor

Yes, I concur with your entire post. I think Freud paints people ugly. I may be something of a misanthrope myself, but you've got to be a loser mentally to make that be what you're about as an artist and what you're thinking about all the time. IMO.

Also, Reagan may have been the only president of the century, of either party, to have understood our founding ideals of individual liberty. I always figured that's why the Left zeroes in on him so much.

I've read that Degas was considered by some to have painted the less attractive side of females. I hadn't really thought so myself, but wonder what your take is on that.

20

posted on

12/08/2005 7:53:29 AM PST

by

Sam Cree

(absolute reality) - "Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one." Albert Einstein)

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first 1-20, 21-23 next last

Disclaimer:

Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual

posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its

management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the

exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.

FreeRepublic.com is powered by software copyright 2000-2008 John Robinson

.jpg)