Posted on 09/25/2005 10:50:47 AM PDT by Republicanprofessor

The title of this first lecture in a new chronological series is: Greco-Roman Realism and Early Christian Abstraction.

Christian abstraction in art? How and why can that be? Well, let’s see how early art developed and why the Christians rebelled against Roman values in art and culture. This is the first “lecture” in my second series of Art Appreciation/Education classes. I figure we need to establish more of a base in how early art developed before we can explore Renaissance and other exciting periods of art.

Let’s look back even to Egyptian art, because then we can see how Greek art diverged from those forms to create greater realism. The fascinating thing about art is how the visual forms reflect the beliefs of the culture. Take a look at the pyramids: those were built about 2500 B.C. to house the mummies and fortunes of three related pharaohs: Khufu, the eldest; Khafre his son and Mycerinus the son of Kafre. The pyramids decrease in size, and in this photo Khufu’s largest pyramid is in the rear while Mycerinus’ smallest is in the foreground (with the little pyramids for his wives).

Just in case the mummified bodies decayed, there were always statues wherein the soul, or ka of the pharaoh could reside, to give him everlasting life. To stay whole forever, the statues are carved of very hard stone (often diorite) and carved in what we call closed forms (there are no parts sticking out to break off). They are cubic and rigid, somewhat like their civilization. There was very little change in Egyptian values and life for close to 3000 years. (That’s amazing; think how quickly our life and culture has changed even in the last 100 years!)

There are many, many images that look just as stiff as this, creating that eternal and unchanging quality forever.

There was one point of change in Egypt under the rule of Akhenaton c. 1390 B.C. Perhaps influenced by Judaism, he changed the former beliefs in many gods (including the pharaoh himself as a god) to a belief in one god: Aton, the sun god. He even changed his name to include -aton at the end of it. The work under his dynasty is much lighter, more lively and happier, with curves showing the appreciation of daily life and love, not the gloomy image of Osiris the god of the death and such deathy concerns. In this image of him and his family, we see an un-ideal pot belly and even the pharaoh playing with his children, something that I’ve never seen in previous Egyptian periods.

Okay, now on to Greece. What similarities and differences do you see between Mycerinus and his (loving) wife on the left and the early Greek youth (or kouros) on the right?

I hope you notice the similar pose, with one leg forward and arms held tightly by their sides. However, the Greeks are much more interested in realism, even in the sixth century B.C. There are more defined muscles and more realistic space between the parts (and thus one can also see the marks of breaks and repairs of broken limbs). My students also note the nudity. In Egyptian times, nudity was a mark of slavery, so pharaohs were always clothed in kilts. In Greek times, there was a development of humanism: the recognition of the power and potential of man. They valued the development of the mind, the body and the arts. Men often exercised nude, and the young beauty of male (and later female bodies) is often celebrated in these nude sculptures. Also note the funny grin on his face, the Archaic smile. It was a way of breathing life into mostly-stiff sculptures of this early, Archaic period.

Now, what differences do you see as Greek art develops?

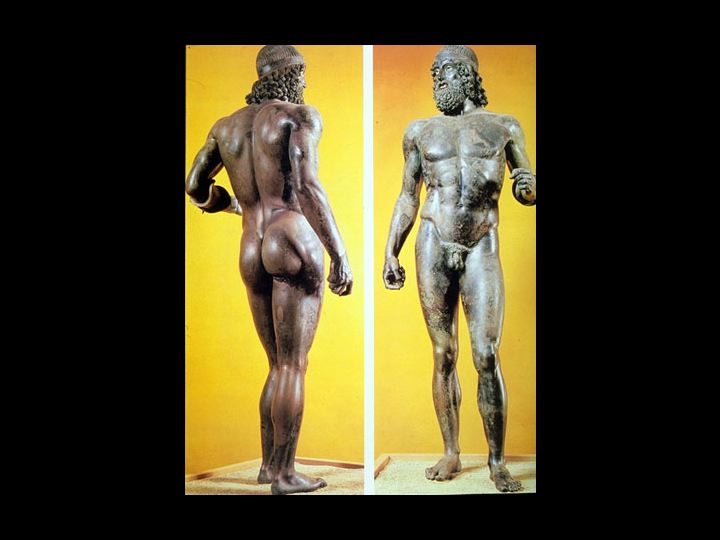

The Greeks soon discover, around 460 B.C., that if one bends the leg, one can show movement that is not possible when one’s knees are locked. This concept is called contrapposto, or weight shift. By the time we get to the Riace bronze, one of my favorites, we see all the qualities of the Severe style. This was a time of war with the Persians, and these men show a warrior’s expression and hardened bodies. The smile is gone because they are alive and seem capable of movement. Do you see a difference between the bronze statue and the even later Hermes and Dionysus? This later piece is softer; war is over and the civilization is softening. Hermes is even in what could be called a somewhat effeminate stance as he holds the baby Dionysus, about to whisk him away from jealous Hera. (Zeus, the philandering main god, is constantly conceiving illegitimate children; here Dionysus is being hurried away to a safe island. I have to say that I do think of a certain recent ex-president and his wife every time I talk about these pieces, even if I don’t know of any illegitimate offspring on their front.)

It is on the statues of women that one notices the virtuosity with drapery that the Greeks developed. The Three Goddesses, c. 440 B.C., were on the top of the Parthenon (in the triangular area called the pediment). They were watching the birth of Athena. There is a wonderful flow to their drapery as the eye travels from one to the other. The Nike of Samothrace is a later, Hellenistic work, showing very open form (that reflects the expansion of the empire under Alexander the Great). She is poised on the front of a ship, and the flowing drapery here shows the wind and sea. We are missing her head and arms, but can you imagine how they would have been shown?

The Romans admired the Greek works tremendously, and they imported and copied these sculptures en masse. These statues then decorated the splendid baths, basilicas, markets and temples. I can’t do Roman architecture justice here, but they were the first to use concrete and the arch (and related vaults and domes) to enclose tremendous spaces. The Roman people were welcomed into these spaces, and I see the arch almost like open arms to illustrate this idea. The Greeks, in contrast, really perceived their temples as sculptural backdrops to their outdoor events, altars, and ceremonies. Only a few select leaders and priests were allowed into the inner areas of Greek temples.

The Romans were a more practical people, and they excelled in specific, realistic portraiture. My favorite is of Marcus Aurelius, the only equestrian statue to survive the dark ages. (They believed for centuries that this was a sculpture of Constantine, the first Christian emperor, so they did not melt it down for the bronze.) Have you seen Gladiator? This is the old, wise emperor seen at the beginning of the film. He was also the first philosopher emperor and his Meditations still can give wise guidance to us today.

I could stop there, but I really want to make the next contrast very strongly, so I am plunging onward. Constantine recognized Christianity in 323 A.D, and the Christians were then allowed to build and create art publicly. But they wanted their work to be different from that of the Romans, and they also believed in spirituality and heaven as more important than material life here on earth. Thus their works will eschew the (wonderful) realism of Marcus Aurelius for a very flat (and yet spiritual) abstraction.

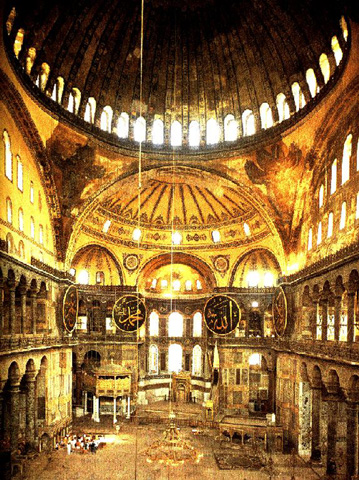

The Byzantine architects used the Roman vaulting system to create splendid basilicas where God was shown through space and light instead of graven images. The left building is Hagia Sophia from Istanbul and is now a mosque; but originally it was the private chapel of Emperor Justinian, built in only five years, 532-37 A.D. The interior decoration at the time was only golden mosaics. (The images of Jesus were added later, and the Islamic medallions even later.) The central dome reaches to 181 feet, with domes and half-domes billowing out from it, with forty windows at its base.

Justinian also built the awesome San Vitale second to the left above, at about the same time, 526-547 A.D. Its architecture is also wonderfully complex (but too much to deal with now). Inside, he had mosaics of himself and his wife. Now, how realistic are these images? Aren’t these figures as flat as paper dolls, and almost as abstract? That is because Christians did not want to stress physical, corporeal images. Instead, they are flat and body-less, concentrating on the spiritual. The gold background is typical of these Byzantine works, showing paradise.

From this point on, artists did not look or create images from life. They copied images from other art instead, so for the next 700 years Christian art is very abstract. The height of this is from the Irish manuscripts of the years 800. Three of the images below are from the Book of Kells, the Lindesfarne Gospel (from about 800) and the Gospel Book of Otto III from about 900. The others are from the twentieth century and could also be seen as spiritual in their own way. For they, too, are moving away from a tight realism to explore color and light in a free floating way.

Now, I’m curious as to how Freepers respond to these abstract images. Three of them are very Christian in orientation but are also very abstract. Does that make them less effective? Abstraction is thus not blasphemous; and in this case physical realism would be sinful.

In the next “class,” we’ll see how in the Renaissance, with its “rebirth” of Greco-Roman values and humanism, artists will develop realistic anatomy with often Christian content.

Art Appreciation/Education ping.

Let me know if you want on or off this list.

Art ping list, in case some of you are not on the other ping list.

Let Sam Cree or me know if you want on or off this art ping list.

I'm always interested in the dialogue that emerges from these threads as much as from my original post, so let's have at it.

Please add me to your ping list. I'm teaching my kids using the trivium model this year so we are doing much more with art; especially comparing/contrasting Greek/Roman to Christian influenced works.

Do you think the abstract Christian art was felt to be more in keeping with the biblical ban on graven images?

BTW, I'm not too convinced by the last 2 :-)

I don't see the Frank Stella, the last image, as very spiritual; but he was explicitly inspired by those early Medieval pieces like the ones I posted, so that's why I included him. I do see, and feel, Kandinsky as very spiritual. His work just soars and raises my spirits (mood). But we dealt with him before.

What the last two images you show lack, what is present in the more abstract Christian images, is a demonstration of skill. The modern abstractions, regardless of how much skill someone with an art degree might read into them, or even how much skill they actually took to create, they do not give that immediate sense of rarity, of preciousness that the obviously skilled art shown prior evokes even to the untrained eye.

The modern art world today strikes me, a layman, as very schizophrenic. Abstract art tries to communicate something meaningful to me, but fails, because it lacks skill. Realistic art can be quite technically skillful, but is too often hollow, from lack of meaning and robotic composition.

The early Christian and the Greco-Roman Realism pictured above demonstrate both skill and a purity of idea and intent that I find sadly lacking in most art today.

What strikes me about the Egyptian sculpture is not how unrealistic they are compared to later Greek ones, but how much *more* realistic they are than the contemporary Egyptian graphic art. Sculpture like that would seem to require a good understanding of 3-dimensional space, yet their murals and such insist on using this unrealistic lateral POV with no perspective (such as in the bas relief of Akhenaton you posted). Do you have any thoughts on the relationship between realistic depth in sculpture vs. 2-dimensional representations, and why the Egyptians eschewed perspective?

P.S., the last two 'Christian abstract' pieces look like worthless tripe.

Photographs don't usually manage to convey the feeling of spirituality that the architecture conveys when one is there in person. I say this as a not particularly religious person.

Anyhow, this photo of a crypt at Winchester Cathedral comes close.

Sam,

That work looks more Romanesque than Gothic because of the rounded arches. This crypt was the earliest part of what developed to be a (very gothic) Winchester Cathedral. Sometimes these buildings took over 100 years to build. I just love Romanesque architecture and find it to be very spiritual, perhaps because of the arching, heaven-like space we are put into.

Also, the St. John Carpet cross page is one of four, IIRC, which are dividing pages preceding the Gospels.

The Irish Gospels did not shy away from depictions of humans, with depictions of the Saints with their symbols, like St. Luke and a winged bull.

The Egyptians had a very conceptual kind of art. They showed what was the most representative parts of the body. Thus the face was in profile, the shoulders in a frontal view, the legs and feet in profile. It was just as regimented as the sculpture, but because sculpture is 3-D, it looks more realistic.

St. Matthew, from the Lindesfarne Gospels.

I don't think that the manuscript illuminations are so much abstractions as they are codes. They are packed with referential symbolism. Many of the elements are traditional shorthand for Saintly aspects or story points. They were more in the line of illustrations of concepts.

Granted, the lines and perspectives are much flattened, but not appreciatively more so than the mosaics of Pompeii or Hellenistic vase decorations, for example. As Sam Cree pointed out, it is easier to see realistic proportion and perspective in sculpture, and here you are comparing apples to oranges.

I confess to not remembering exactly what romanesque architecture is...seems that I like it, though. I'm still awed by the gothic cathedrals, but haven't found a photo to do one justice.

I had another thought on absractions in realistic art and why they are important - since it's a truism that even in realism, art can't reproduce reality, it follows that to illustrate reality, something of the abstract must be introduced by the artist, something of himself, in other words. Done skillfully, it produces "great" art. I suppose this is all very obvious, but it's making me happy to figure it out.

I think we differ on the definition of abstract art or abstraction. I have always seen abstraction as anything that moves away from from perfect realism, to a small or great degree, to emphasize other aspects that the artists wish. But to double-check, I looked up the definition on line and found essentially the same thing:

From ArtLex dictionary on line, a definition of abstraction: "Imagery which departs from representational accuracy, to a variable range of possible degrees, for some reason other than verisimilitude. Abstract artists select and then exaggerate or simplify the forms suggested by the world around them."

Thus I do see the Chi Rho page from the Book of Kells and the figurative pages from the Lindisfarne Gospel as definitely abstract. They could have written the XP so much more easily, but they went wild with rich, decorative design to emphasize the wonderful spiritual meaning they saw in the gospels. The little heads are recognizably human, but they cannot be called realistic, so I see them as definitely abstract.

You are quite right that these early manuscripts are laden with symbolism. The ox for St. Luke, etc., as a way to, again, embellish their works with more meaning. One can get very absorbed studying these symbols, narratives and design. They are very rich. I enjoy them, but they are definitely not my specialty.

Now, the two twentieth century pieces that I included do border on non-objective art, a fancy term for works that do not even begin with reality but come solely from the artist's mind (the term that many mean when they use the term "abstract." )

Now, the Kandinsky, on the left, still seems somewhat (although minimally) based in earthly reality. I see hills and a tower and perhaps a rainbow, so then that would be seen as an abstraction. However, the Frank Stella on the right is definitely non-objective. I couldn't find the other image again and chose a sculpture that really activates 3-D space. I'm still uncertain as to how great his work is. It works well on a superficial, energetic level; I'm not sure that it touches my soul (as do almost all the other works I've shown here).

Now, art is so subjective. If you don't see the hills and rainbow that I do, then you might see Kandinsky's work as non-objective, and much of his work is like that. I show his work a great deal here on FR because it is difficult and my challenge is to get some FReepers to begin to see some meaning in abstraction. Much of what Kandinsky was doing is freeing line from color and freeing shape from outline and, in general, freeing art from past boundaries. At this point, because the camera can capture perfect reality, artists are exploring their deeper subjective and intuitive emotions and ideas and are transferring these to canvas. This work is harder to understand. I like Kandinsky's work a great deal; but later, postmodern work is a bit too free and formless for me. But that's another story....

But what is the perfect realism of a letterform? At one level, any glyph is an abstraction of an idea into an instantly recognizable code. The letterforms of this comment are just glyphs representing sounds, grouped into lumps representing words. So is the Chi Ro an abstraction of an abstraction, or just a glyph which has been highly decorated?

In terms of stylistic classification, I think the manuscript art has more in common with surrealism than modern "abstract" art. It is not concerned with showing things as they are, in a realistic manner, as it is in invoking a message using a symbolic code.

While this agrees with your definition of abstraction, it goes against the modern concept of what abstract art is. I think the two modern examples you show contain an abstraction that lessens the content, while the medieval examples enrich the content. The Kandinski tells us nothing more about the rainbow than surface coloration. I find nothing spiritual in it beyond a trite use of primary colors; any further depth is entirely subjective from viewer to viewer. Any artist who falls back on the "what do YOU think it means" school of content is merely lazy, or hasn't any real meaning in mind.

The Otto page, OTOH, would have invoked whole layers of ideas in its intended audience, containing direct and recognizable references to their understanding of the spiritual realm.

I guess maybe I'll show and explain some more about Romanesque and Gothic before I move onto Renaissance (in this "lecture" series). I'll have to use a lot of architectural terms, but it is really worth it. These buildings are stunning, and very spiritual.

Until then.

I would point out that the difference between the early Christian abstractions and the contemorary ones is the use of content: the early Christian art evokes concepts of spirituality, virtue and Heaven. The modern abstractions by contrast seem to emphasize pure form and act on the perceptual rather than the conceptual level.

I will continue with your lecture series as the days and weeks pass, thank you.

Perceptual vs. conceptual. Good point; I'll have to think about this more.

Are my own spirits raised more by the perceptual than the conceptual? I do love the concepts behind Chinese painting as well as their visual floating spaces....hmmmm.... And I love the soaring Gothic cathedrals and the concepts therein too....Some other Catholic images seem awfully dogmatic conceptually. Hmmm. Have to ponder this.

Thanks for the thoughts. I look forward to your other ideas as you wade through the series.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.