Cool! Mother of Texas BTTT!

Posted on 03/06/2005 4:44:27 AM PST by Rightly Biased

3 March 1836: Travis' Report and Appeal for Aid for the Alamo. On the night of 3 Mar, Travis sent out the last message from the besieged Alamo with courier John W. Smith. He penetrated enemy lines with the message from Travis to the Texas Independence Convention at Washington-on-the-Brazos which describes the situation at the Alamo in detail:

In the present confusion of the political authorities of the country, and in the absence of the commander in chief, I beg leave to communicate to you the situation of this garrison. You have doubtless already seen my official report of the action of the twenty fifth ult. made on that day to Gen. Sam Houston, together with the various communications heretofore sent by express. I shall therefore confine myself to what has transpired since that date. From the twenty-fifth to the present date the enemy has kept up a bombardment from two howitzers—one a five and a half inch, and the other an eight inch--and a heavy cannonade from two long nine-pounders mounted on a battery on the opposite side of the river at a distance of four hundred yards from our wall. During this period the enemy have been busily employed in encircling us with entrenched encampments on all sides, at the following distance, to wit: In Bexar, four hundred yards west; in Lavileta, three hundred yards south; at the powder house, one thousand yards east of south; at the ditch, eight hundred yards northeast, and at the old mill, eight hundred yards north. Notwithstanding all this, a company of thirty-two men from Gonzales made their way in to us on the morning of the first inst. at three o'clock, and Colonel J. B. Bonham (a courier from Gonzales) got in this morning at eleven o'clock without molestation. I have fortified this place, so that the walls are generally proof against cannon balls and I will continue to entrench on the inside, and strengthen walls by throwing up the dirt. At least two hundred shells have fallen inside our works without having injured a single man; indeed we have been so fortunate as not to lose a man from any cause, and we have killed many of the enemy. The spirits of my men are still high although they have had much to depress them. We have contended for ten days against an enemy whose numbers are variously estimated at from fifteen hundred to six thousand men, with General Ramirez Sesma and Colonel Batres, the aides-de-camp of Santa Anna, at their head. A report was circulated that Santa Anna himself was with the enemy, but I think it was false. A reinforcement of about one thousand men is now entering Bexar, from the west, and I think it more than probable that Santa Anna is now in town, from the rejoicing we hear. Col. Fannin is said to be on the march to this place with reinforcements, but I fear it is not true, as I have repeatedly sent to him for aid without receiving any. Colonel Bonham, my special messenger, arrived at La Bahia fourteen days ago, with a request for aide and on the arrival of the enemy in Bexar, ten days ago, I sent an express to Colonel F. which arrived at Goliad on the next day, urging him to send us reinforcements; none have yet arrived. I look to the colonies alone for aid; unless it arrives soon, I shall have to fight the enemy on his own terms. I will, however, do the best I can under the circumstances; and I feel confident that the determined valor and desperate courage heretofore exhibited by my men will not fail them in the last struggle; and although they may be sacrificed to the vengeance of a Gothic enemy, the victory will cost the enemy so dear, that it will be worse to him than a defeat. I hope your honorable body will hasten on reinforcements ammunition, and provisions to our aid as soon as possible. We have provisions for twenty days for the men we have. Our supply of ammunition is limited. At least five hundred pounds of cannon powder, and two hundred rounds of six., nine, twelve and eighteen pound balls, ten kegs of rifle powder and a supply of lead, should be sent to the place without delay under a sufficient guard. If these things are promptly sent, and large reinforcements are hastened to this frontier, this neighborhood will be the great and decisive ground. The power of Santa Anna is to be met here, or in the colonies; we had better meet them here than to suffer a war of devastation to rage in our settlements. A blood red banner waves from the church of Bexar, and in the camp above us, in token that the war is one of vengeance against rebels; they have declared us as such; demanded, that we should surrender at discretion, or that this garrison should be put to the sword. Their threats have had no influence on me or my men, but to make all fight with desperation, and that high souled courage which characterizes the patriot, who is willing to die in defense of his country's liberty and his own honor. The citizens of this municipality are all our enemies, except those who have joined us heretofore. We have but three Mexicans now in the fort; those who have not joined us, in this extremity, should be declared public enemies, and their property should aid in paying the expenses of the war. The bearer of this will give your honorable body a statement more in detail, should he escape through the enemy's lines. God and Texas---Victory or Death. P.S. The enemy's troops are still arriving, and the reinforcements will probably amount to two or three thousand.

On 5 Mar, General Santa Anna issued the formal written order to his troops to storm the Alamo garrison (translated from the Spanish):

To the Generals, Chiefs of Sections and Commanding Officers: The time has come to strike a decisive blow upon the enemy occupying the Fortress of the Alamo. Consequently, His Excellency, the General in Chief, has decided that tomorrow at 4 o'clock a.m., the columns of attack shall be stationed at musket-shot distance from the first entrenchments, ready for the charge, which shall commence, at a signal given with the bugle, from the Northern Battery. The first column will be commanded by General Don Martin Perfecto de Cos, and, in his absence, by myself. The Permanent Battalion of Aldama (except the company of Grenadiers) and the three right center companies of the Active Battalion of San Luis, will comprise the first column. The second column will be commanded by Colonel Don Francisco Duque, and, in his absence, by General Don Manuel Fernindez Castrillon; it will be composed of the Active Battalion (except the company of Grenadiers) and the three remaining center companies of the Active Battalion of San Luis. The third column will be commanded by Colonel Jose Maria Romero and in his absence Mariano Salas; it will be Composed of the permanent Battalion Of Matamoros and Jimenes. The fourth column will be commanded by Colonel Juan Morales, and in his absence, by Colonel Jose Minon; it will be composed of the light companies of the Battalions of Matamoros and Jimenes and of the Active Battalion of San Luis. His Excellency the General in Chief will, in due time designate the points of attack, and give his instructions to the Commanding Officers. The reserve will be composed of the Battalion of Engineers and the five companies of Grenadiers of the Permanent Battalions of Matamoros, Jimenes and Allama, and the Active Battalions of Toluca and San Luis. The reserve will be commanded by the General in Chief in person, during the attack; but General Augustin Amat will assemble this party which will report to him, this evening at 5 o’clock, to be marched to the designated station. The first column will carry ten ladders, two crowbars and two axes; the second, ten ladders; the third, six ladders; and the fourth, two ladders. The men carrying the ladders will sling their guns on their shoulders, to be enabled to place the ladders wherever they may be required. The companies of Grenadiers will be supplied with six packages of cartridges to every man, and the center companies with two packages and two spare flints. The men will wear neither overcoats nor blankets nor anything that may impede the rapidity of their motions. The Commanding Officers will see that the men have their chin straps of their caps down, and that they wear either shoes or sandals. The troops composing the columns of attack will turn in to sleep at dark; to be in readiness to move at 12 o'clock at light. Recruits deficient in instruction will remain in their quarters. The arms, principally the bayonets, should be in perfect order. As soon as the moon rises, the center companies of the Active Battalion of San Luis will abandon the points they are now occupying on the line, in order to have time to prepare. The cavalry, under Colonel Joaquin Ramirez y Sesma, will be stationed at the Alameda, saddling up at 3 o'clock a.m. It shall be its duty to scout the country, to prevent the possibility of an escape. The honor of the nation being interested in this engagement against the bold and lawless foreigners who are opposing us, His Excellency expects that every man will do his duty, and exert himself to give a day of glory to the country, and of gratification to the Supreme Government, who will know how to reward the distinguished deeds of the brave soldiers of the Army of Operations.

On 6 March 1836 about 3:00 AM, Andrew Kent's daughter Mary Ann Kent related that the sound of distant cannons woke the family. Lying on pallets spread on the floor of the Zumwalt residence, the children could hear and feel the boom of the cannons as they fired 70 miles away in San Antonio. By daybreak there was silence which continued past noon and then sundown and the next day and the next. Travis had sent word to Gonzales that he would fire three daily "all’s well" volleys from the walls of the garrison as long as it was in Texan hands. For over six days the people of Gonzales and riders that ventured close to San Antonio to try to hear the three times per day volleys heard nothing. Anxiety mounted and the worst was feared among the residents.

There were few that did not have a relative or close friend in the garrison.

We are planning a Texas History Spring Break Extravaganza (actually, Washington-on-the-Brazos, Independence and maybe San Jacinto at this point). We will be staying in the Bryan/College Station area. If any of you can think of interesting side trips we can make in this area (we've already done San Antonio and the missions), please let me know.Hmmmmm. Perhaps someone can offer a suggestion or two ?? .....

Oh, Lord, it's hard to be humble when you're a Texan. Some may try; few actually achieve it. Some don't even care to try. There's just so much to be proud about that achieving humility is too time consuming.

Blue Bell Creamries..... Brenham Tx

Sam Houton Museum .. Huntsville Tx

Texas Prison Museum .. Huntsville Tx

From Houston, I send these greetings:

Remember the Alamo!

Remember Goliad!

God Bless Texas!

...and...

Hook 'em, Horns!

:^D

I do remember my first visit to the Alamo and the church where the bones of the heros are contained in a sarcophocus {sic}.

The Daughters of the Alamo maintain the site and commemorate the sacrifice that those gallant men.

I also remember, as a young man, the Disney three part special "Davy Crocket". It was 1955 and my brother was young enough to wear his coonskin cap to school while kids my age wanted black leather jackets and Elvis duck tail haircuts! God! Fess Parker was magnificent as he stood his ground at the Alamo?

"After ten days of siege, of cannon battery and counterbattery, which the Texans lacked powder to pursue effectively, and of numerous sallies by the defenders at night, and after dozens of Mexican gunners had been picked off by rifle fire, the besieging army worked it's guns in close. On March 5 a breach was battered in the Alamo east wall.

________

[Santa Anna's] Orders for the assault were issued on the afternoon of March 5.

Five battalions, about 4000 men, were committed to the action. Ony trained soldiers were used; others, whose training was not considered sufficient were confined to barracks. The attack order was efficiently written and issued, and ended, since this was a professional, more than a patriot army, as follows:

"The honor of the nation being concerned in this engagement against the lawless foreigners who oppose us, His Excellency expects every man to do his duty and exert to allow the country a day of glory, and gratification to the Supreme Government, who will know how to reward distinguished deeds by the brave soldiers of the Army of Operations."

The brigades that assembled in the chilly pre-dawn darkness on the open fields beyond the Alamo on March 6th were veteran, and good. They were well fed, smartly uniformed, and armed with flintlock muskets, which were still the standard weapon of every army of the day. Each man carried a long bayonet in good order; the Chief of Staff's instructions emphasized this.

Despite some weakness in the top commands, where matters devolved on politics, the officer corps was professional, and competent. Throughout the officers were sprinkled numerous Europeans, most of whom were veterans of the Napoleonic or other respectable wars.

The tatics used were the standard Napoleonic techniques; attack in columns, cavalry on the flanks and in reserve, batteries to soften the enemy before the charge. Two weaknesses here, however, glared: Santa Anna lacked sufficient guns to give the enemy a sufficient Napoleonic blasting, and his heavy cuirassiers could not hurl their shock action against thick limestone walls. The assault had to be infantry in columns, bearing bayonets and scaling ladders. Probably, no marshal of France would have faulted the organization or the charge. But neither Napoleonic marshals, nor Santa Anna had ever assaulted American riflemen enscounced behind high walls.

Nor could they know that British army instructions of the time warned that American riflemen, behind breastworks, could be attacked frontally only at unacceptable cost. British officers had seen the Sutherland Highlanders shot to a standstill, and battalions chopped to pieces, before the massed cotton bales at New Orleans in 1815. There, Jackson, and men like these men in the Alamo, had commenced firing at the unheard of range of three hundred yards. At one hundred yards, a British, or Mexican, musket could not hit a man-sized target one time in ten.

Both history and legend record that Travis gave only one coherent order to his awakened, stumbling men: "The Mexicans are upon us - give 'em Hell!"

The Alamo cannon smashed some columns, then the flat crack of small bore rifles swelled. Flame and lead sleeted and sleeted again from the sprawling walls. Marksmanship was hardly an American, rather a Western, tradition. The Tennesseeans, Kentuckians, and all the others shot and seldom missed. On the frontier men got guns at about the age of seven; and a boy or man who missed with a single-shot weapon usually went hungry, or lost his hair.

The smartly dressed columned army, marching with it's regimentals, bayonets flashing in the dawn, it's bands blaring the "Deguello", a blood-tune that reached back to Moorish days, stumbled into a swarm of lead. The first ranks went down, then the ranks behind them. Everywhere, colonels and majors and captains cried out and fell. It was an American tradition to shoot at braid.

The first assault never reached the walls. The defenders sent up a ragged cheer; they were fighting for their lives.

The bands roared, and the Mexican bugles sent the columns forward again. Now, the ladders went up the walls - but they could not stay. Fire, ram, put powder, patch, shot, ram, spash the pan, aim, fire - this was weapons handling the Mexican officers had never seen. Some felt there must be a hundred men inside the fortress merely loading guns. At the wall the ladders wavered, then collapsed. A scattered trail of uniformed corpses marked the Mexican retreat.

But massed musketry had knocked many Texans off the walls, this time; the great fortress had always been thinly held with less than two hundred men. There were now some sections with few defenders, and several Mexican officers had spotted weak points where the fire was less.

These brigades were brave men, and as disciplined, if not as stolid, as any British grenadiers. After several hours, in which battalions were regrouped and the reserve called, the Mexicans came back, at about eight in the morning. Santa Anna remainded across the river in San Antonio. If he sensed what was happening to his army - the deeper wounds beyond the dead and groaning wounded he could see - he gave no sign. One of his column commanders was already dead, but the others beat the battalions back into line. Now, from all four sides of the Alamo, a new general assault began. This time, the ladders went up against the north wall and stayed. Mexican soldiers, sprayed into the fortress like scuttling ants. Men fell all over the walls. Only flaming courage, and the determined leadership of a number of Mexican junior officers took the charge into the heart of the Alamo.

Now, the defenders no longer fought to win. They charged into the Mexican soldiers to kill as many as they could. These troops had seen much cruelty and understood it; they had never seen the savagery of the Trans-Appalachian American at close range. The Texans had no bayonets, but by Mexican standards they were enormous men, towering a head higher or more. They smashed, butted, used tomahawks and knives. They fought as palladins, each touchy of his rights and his own section of the wall. Now, they died as palladins, each with his ring of surrounding dead.

A terrible and understandable fury and hatred suffused the Mexicans who broke into the courtyard. They had been punished in the assault as they had never been punished before. Inside, at last they could employ their bayonets. They had crushing numbers. They killed, and after they killed, mutilated the bleeding corpses with a hundred wounds. At the end, as the defenders were at last exterminated, Mexican officers admitted they lost control. The one woman in the Alamo, the wife of Texas lieutenant, who with a Negro slave was spared expressly at Santa Anna's orders, saw Jim Bowie's body tossed aloft on a dozen bayonets. He had been taken on his deathbed. Mexican accounts say, probably accurately, that a few defenders vainly attempted to surrender. These, who may have included Crockett, were shot.

No white defender survived; as the inscription on a later monument stated, Thermopylae had its messenger, the Alamo had none. Mrs. Dickenson, the Negro, and several Mexican women and children werer the only ones to tell the story. These Santa Anna released, not so much in gallantry as in the trust that their tale would spread terror throughout Texas.

At nine o'clock, March 6, 1836, five hours after it began, the assault was over.

The Alamo had fallen.

Gallantry of itself in battle is worthless, until it's results may be assessed. Travis to begin with had given Anglo-Texans twelve precious days. The five hour engagement on March 6 extended his country several weeks. These were weeks without which Anglo-Texans could not have survived.

When the fury of the assault passed, the tolling bells of San Fernando rang out over a shattered army. The Battalion of Toluca, the assault shock force of 800 men, had 670 killed. The other battalions had lost in each case approximately 25 percent. In all, there were nearly 1600 Mexican dead. The figures are reliable; they were made by Alcalde Francisco Ruiz of San Antonio, who also indicated Santa Anna left 500 wounded when at last he was able again to march. This Santa Anna's secretary again confirmed.

These were casualties to shatter the morale of any army. The came from the permanent, best-trained battalions, the flower of the Mexican force. A thousand Mexican settlers now flocked to Santa Anna's cause, but these could hardly fill the ranks. The Mexican Army, like the Roman, was organized and disciplined; new recruits under the Mexican system could not be trained in weeks. Nor did Mexican civilians, unlike North Americans, learn to use firearms as youths.

The damage to the soul of Santa Anna's army was not to be revealed for another forty-six days. At the Alamo, only the loss in blood and bone could be assessed. But this was enough to sate even Travis' and Bowie's bloody-minded ghosts - here for the first time, the legend of the diablos tejanos , the Devil Texans, was spawned, a shuddery legend that would go into Mexican folklore.

The casualty figures were to be disputed over the years, mainly by Mexican historians. Santa Anna's official report to his Supreme Government stated 600 Americans had been killed, and minimized his own losses to 70 dead. Other Mexicans later claimed at least 1500 defenders had been behind the walls of the Alamo. But Alcalde Ruiz stated positively that the number of Texan bodies burned under his supervision was exactly 182. Ruiz also found no room to bury all the Mexican dead in the San Fernando churchyard; he ordered many corpses put into the San Antonio River.

The charred remains of the Alamo dead were dumped into a common grave. Its location went unrecorded and was never found.

Whether the numbers engaged on each side, whether 1600 Mexican soldiers out of 5000 killed, or 600 out of 1800, the historic result of the battle remains the same, and is indisputable.

While the funeral pyres and campfires of the groaning Mexican army were lit on the night of Sunday, March 6, Santa Anna penned a report of a glorious victory for the Mexican nation. But Colonel Juan Nepomuceno Almonte, who had something of a classical education, was heard to repeat King Pyrrhus' desparing remark:

Whatever mystical title to the soil of Texas Travis' stand had won, Santa Anna had paid too great a price to gain this ground."

T.R. Fehrenbach, "Lone Star"

The tale of the Alamo is simply unmatched in American history. It's bravery beyond understanding.

Great post TC! Thanks.

An excerpt:

The damage to the soul of Santa Anna's army was not to be revealed for another forty-six days. At the Alamo, only the loss in blood and bone could be assessed. But this was enough to sate even Travis' and Bowie's bloody-minded ghosts - here for the first time, the legend of the diablos tejanos, the Devil Texans, was spawned, a shuddery legend that would go into Mexican folklore.

< snip >

The charred remains of the Alamo dead were dumped into a common grave. Its location went unrecorded and was never found.

Whether the numbers engaged on each side, whether 1600 Mexican soldiers out of 5000 killed, or 600 out of 1800, the historic result of the battle remains the same, and is indisputable.

While the funeral pyres and campfires of the groaning Mexican army were lit on the night of Sunday, March 6, Santa Anna penned a report of a glorious victory for the Mexican nation. But Colonel Juan Nepomuceno Almonte, who had something of a classical education, was heard to repeat King Pyrrhus' desparing remark:

Whatever mystical title to the soil of Texas Travis' stand had won, Santa Anna had paid too great a price to gain this ground."

Lone Star Ping

A big Texas bump to that.

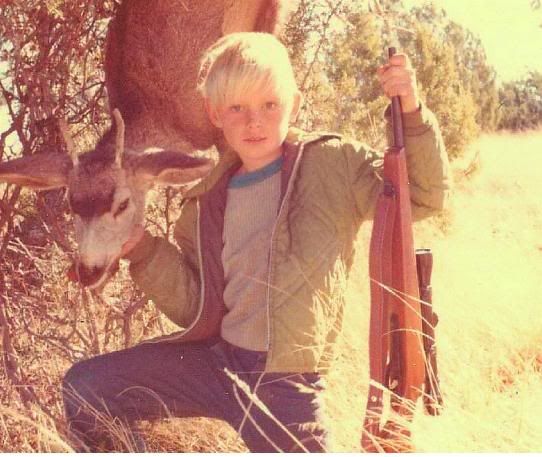

Alpine, Texas 1971

I love to see that shine in a boy's eyes when he kills his first deer!

I killed my first at eight, and I'll bet I looked just like that!

Alpine, huh? That's mulie country! Good show, gunner!

Walt Whitman wrote a moving poem about the massacre.

Danged if I can't help getting excited every time.

I'm thankful every day that I was born a Texan and taught

to shoot early & often. You never know when that might come in handy.

One thing puzzles me. I once read a list (I don't have it now) of the names of the men who died defending the Alamo (some names are lost). I'm sure that a good many more than three of the names were Hispanic.

Bump to read later. Thanks for the thread!

I shall never surrender nor retreat: then I call on you, in the name of liberty, of patriotism, and of every thing dear to the American character, to come to our aid, with all possible despatch.

I never noticed that before. He didn't say "Texan" character, he said "American." That's significant, although I couldn't begin to tell why.

Here's some food for thought, though. It took a certain kind of man (and woman) to brave the harsh frontier & the Indians to come to Texas in the early 1800s. It was full of outlaws, rattlesnakes, and Indians who didn't take kindly to people encroaching on their land. I guess the Texans inherited their frontier spirit from their late-1700s, Revolutionary/Patriot ancestors, and it eventually morphed into the uniquely Texan bravado spirit that it is today.

See, Pardek? It all originated from you Yankees, so now you can stop rolling your eyes (although I'll acknowledge it must be nauseating to people who don't understand it). :-)

A lot of the early comers to Texas had lived or grown up on the edge of things in the Carolinas, Kentucky, and Tennessee...a lot the characteristics that went into those people made up a lot of the Texican character too...willingness to fight for home and hearth, and a lack of fear about living on the edge to get a better life.

Austin's father had been one of the early American comers to Spanish Illinois, (soon to be Missouri), a man with foresight and the desire to make something of the American wilderness. He and several others attempted to found a bank to aid in the growing business in St. Louis...wonder what would have happened to American history if his bank hadn't foundered and he went to plan two, set up a colony of Americans in Texas?

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.