Cool! Mother of Texas BTTT!

Posted on 03/06/2005 4:44:27 AM PST by Rightly Biased

We are planning a Texas History Spring Break Extravaganza (actually, Washington-on-the-Brazos, Independence and maybe San Jacinto at this point). We will be staying in the Bryan/College Station area. If any of you can think of interesting side trips we can make in this area (we've already done San Antonio and the missions), please let me know.Hmmmmm. Perhaps someone can offer a suggestion or two ?? .....

Oh, Lord, it's hard to be humble when you're a Texan. Some may try; few actually achieve it. Some don't even care to try. There's just so much to be proud about that achieving humility is too time consuming.

Blue Bell Creamries..... Brenham Tx

Sam Houton Museum .. Huntsville Tx

Texas Prison Museum .. Huntsville Tx

From Houston, I send these greetings:

Remember the Alamo!

Remember Goliad!

God Bless Texas!

...and...

Hook 'em, Horns!

:^D

I do remember my first visit to the Alamo and the church where the bones of the heros are contained in a sarcophocus {sic}.

The Daughters of the Alamo maintain the site and commemorate the sacrifice that those gallant men.

I also remember, as a young man, the Disney three part special "Davy Crocket". It was 1955 and my brother was young enough to wear his coonskin cap to school while kids my age wanted black leather jackets and Elvis duck tail haircuts! God! Fess Parker was magnificent as he stood his ground at the Alamo?

"After ten days of siege, of cannon battery and counterbattery, which the Texans lacked powder to pursue effectively, and of numerous sallies by the defenders at night, and after dozens of Mexican gunners had been picked off by rifle fire, the besieging army worked it's guns in close. On March 5 a breach was battered in the Alamo east wall.

________

[Santa Anna's] Orders for the assault were issued on the afternoon of March 5.

Five battalions, about 4000 men, were committed to the action. Ony trained soldiers were used; others, whose training was not considered sufficient were confined to barracks. The attack order was efficiently written and issued, and ended, since this was a professional, more than a patriot army, as follows:

"The honor of the nation being concerned in this engagement against the lawless foreigners who oppose us, His Excellency expects every man to do his duty and exert to allow the country a day of glory, and gratification to the Supreme Government, who will know how to reward distinguished deeds by the brave soldiers of the Army of Operations."

The brigades that assembled in the chilly pre-dawn darkness on the open fields beyond the Alamo on March 6th were veteran, and good. They were well fed, smartly uniformed, and armed with flintlock muskets, which were still the standard weapon of every army of the day. Each man carried a long bayonet in good order; the Chief of Staff's instructions emphasized this.

Despite some weakness in the top commands, where matters devolved on politics, the officer corps was professional, and competent. Throughout the officers were sprinkled numerous Europeans, most of whom were veterans of the Napoleonic or other respectable wars.

The tatics used were the standard Napoleonic techniques; attack in columns, cavalry on the flanks and in reserve, batteries to soften the enemy before the charge. Two weaknesses here, however, glared: Santa Anna lacked sufficient guns to give the enemy a sufficient Napoleonic blasting, and his heavy cuirassiers could not hurl their shock action against thick limestone walls. The assault had to be infantry in columns, bearing bayonets and scaling ladders. Probably, no marshal of France would have faulted the organization or the charge. But neither Napoleonic marshals, nor Santa Anna had ever assaulted American riflemen enscounced behind high walls.

Nor could they know that British army instructions of the time warned that American riflemen, behind breastworks, could be attacked frontally only at unacceptable cost. British officers had seen the Sutherland Highlanders shot to a standstill, and battalions chopped to pieces, before the massed cotton bales at New Orleans in 1815. There, Jackson, and men like these men in the Alamo, had commenced firing at the unheard of range of three hundred yards. At one hundred yards, a British, or Mexican, musket could not hit a man-sized target one time in ten.

Both history and legend record that Travis gave only one coherent order to his awakened, stumbling men: "The Mexicans are upon us - give 'em Hell!"

The Alamo cannon smashed some columns, then the flat crack of small bore rifles swelled. Flame and lead sleeted and sleeted again from the sprawling walls. Marksmanship was hardly an American, rather a Western, tradition. The Tennesseeans, Kentuckians, and all the others shot and seldom missed. On the frontier men got guns at about the age of seven; and a boy or man who missed with a single-shot weapon usually went hungry, or lost his hair.

The smartly dressed columned army, marching with it's regimentals, bayonets flashing in the dawn, it's bands blaring the "Deguello", a blood-tune that reached back to Moorish days, stumbled into a swarm of lead. The first ranks went down, then the ranks behind them. Everywhere, colonels and majors and captains cried out and fell. It was an American tradition to shoot at braid.

The first assault never reached the walls. The defenders sent up a ragged cheer; they were fighting for their lives.

The bands roared, and the Mexican bugles sent the columns forward again. Now, the ladders went up the walls - but they could not stay. Fire, ram, put powder, patch, shot, ram, spash the pan, aim, fire - this was weapons handling the Mexican officers had never seen. Some felt there must be a hundred men inside the fortress merely loading guns. At the wall the ladders wavered, then collapsed. A scattered trail of uniformed corpses marked the Mexican retreat.

But massed musketry had knocked many Texans off the walls, this time; the great fortress had always been thinly held with less than two hundred men. There were now some sections with few defenders, and several Mexican officers had spotted weak points where the fire was less.

These brigades were brave men, and as disciplined, if not as stolid, as any British grenadiers. After several hours, in which battalions were regrouped and the reserve called, the Mexicans came back, at about eight in the morning. Santa Anna remainded across the river in San Antonio. If he sensed what was happening to his army - the deeper wounds beyond the dead and groaning wounded he could see - he gave no sign. One of his column commanders was already dead, but the others beat the battalions back into line. Now, from all four sides of the Alamo, a new general assault began. This time, the ladders went up against the north wall and stayed. Mexican soldiers, sprayed into the fortress like scuttling ants. Men fell all over the walls. Only flaming courage, and the determined leadership of a number of Mexican junior officers took the charge into the heart of the Alamo.

Now, the defenders no longer fought to win. They charged into the Mexican soldiers to kill as many as they could. These troops had seen much cruelty and understood it; they had never seen the savagery of the Trans-Appalachian American at close range. The Texans had no bayonets, but by Mexican standards they were enormous men, towering a head higher or more. They smashed, butted, used tomahawks and knives. They fought as palladins, each touchy of his rights and his own section of the wall. Now, they died as palladins, each with his ring of surrounding dead.

A terrible and understandable fury and hatred suffused the Mexicans who broke into the courtyard. They had been punished in the assault as they had never been punished before. Inside, at last they could employ their bayonets. They had crushing numbers. They killed, and after they killed, mutilated the bleeding corpses with a hundred wounds. At the end, as the defenders were at last exterminated, Mexican officers admitted they lost control. The one woman in the Alamo, the wife of Texas lieutenant, who with a Negro slave was spared expressly at Santa Anna's orders, saw Jim Bowie's body tossed aloft on a dozen bayonets. He had been taken on his deathbed. Mexican accounts say, probably accurately, that a few defenders vainly attempted to surrender. These, who may have included Crockett, were shot.

No white defender survived; as the inscription on a later monument stated, Thermopylae had its messenger, the Alamo had none. Mrs. Dickenson, the Negro, and several Mexican women and children werer the only ones to tell the story. These Santa Anna released, not so much in gallantry as in the trust that their tale would spread terror throughout Texas.

At nine o'clock, March 6, 1836, five hours after it began, the assault was over.

The Alamo had fallen.

Gallantry of itself in battle is worthless, until it's results may be assessed. Travis to begin with had given Anglo-Texans twelve precious days. The five hour engagement on March 6 extended his country several weeks. These were weeks without which Anglo-Texans could not have survived.

When the fury of the assault passed, the tolling bells of San Fernando rang out over a shattered army. The Battalion of Toluca, the assault shock force of 800 men, had 670 killed. The other battalions had lost in each case approximately 25 percent. In all, there were nearly 1600 Mexican dead. The figures are reliable; they were made by Alcalde Francisco Ruiz of San Antonio, who also indicated Santa Anna left 500 wounded when at last he was able again to march. This Santa Anna's secretary again confirmed.

These were casualties to shatter the morale of any army. The came from the permanent, best-trained battalions, the flower of the Mexican force. A thousand Mexican settlers now flocked to Santa Anna's cause, but these could hardly fill the ranks. The Mexican Army, like the Roman, was organized and disciplined; new recruits under the Mexican system could not be trained in weeks. Nor did Mexican civilians, unlike North Americans, learn to use firearms as youths.

The damage to the soul of Santa Anna's army was not to be revealed for another forty-six days. At the Alamo, only the loss in blood and bone could be assessed. But this was enough to sate even Travis' and Bowie's bloody-minded ghosts - here for the first time, the legend of the diablos tejanos , the Devil Texans, was spawned, a shuddery legend that would go into Mexican folklore.

The casualty figures were to be disputed over the years, mainly by Mexican historians. Santa Anna's official report to his Supreme Government stated 600 Americans had been killed, and minimized his own losses to 70 dead. Other Mexicans later claimed at least 1500 defenders had been behind the walls of the Alamo. But Alcalde Ruiz stated positively that the number of Texan bodies burned under his supervision was exactly 182. Ruiz also found no room to bury all the Mexican dead in the San Fernando churchyard; he ordered many corpses put into the San Antonio River.

The charred remains of the Alamo dead were dumped into a common grave. Its location went unrecorded and was never found.

Whether the numbers engaged on each side, whether 1600 Mexican soldiers out of 5000 killed, or 600 out of 1800, the historic result of the battle remains the same, and is indisputable.

While the funeral pyres and campfires of the groaning Mexican army were lit on the night of Sunday, March 6, Santa Anna penned a report of a glorious victory for the Mexican nation. But Colonel Juan Nepomuceno Almonte, who had something of a classical education, was heard to repeat King Pyrrhus' desparing remark:

Whatever mystical title to the soil of Texas Travis' stand had won, Santa Anna had paid too great a price to gain this ground."

T.R. Fehrenbach, "Lone Star"

The tale of the Alamo is simply unmatched in American history. It's bravery beyond understanding.

Great post TC! Thanks.

An excerpt:

The damage to the soul of Santa Anna's army was not to be revealed for another forty-six days. At the Alamo, only the loss in blood and bone could be assessed. But this was enough to sate even Travis' and Bowie's bloody-minded ghosts - here for the first time, the legend of the diablos tejanos, the Devil Texans, was spawned, a shuddery legend that would go into Mexican folklore.

< snip >

The charred remains of the Alamo dead were dumped into a common grave. Its location went unrecorded and was never found.

Whether the numbers engaged on each side, whether 1600 Mexican soldiers out of 5000 killed, or 600 out of 1800, the historic result of the battle remains the same, and is indisputable.

While the funeral pyres and campfires of the groaning Mexican army were lit on the night of Sunday, March 6, Santa Anna penned a report of a glorious victory for the Mexican nation. But Colonel Juan Nepomuceno Almonte, who had something of a classical education, was heard to repeat King Pyrrhus' desparing remark:

Whatever mystical title to the soil of Texas Travis' stand had won, Santa Anna had paid too great a price to gain this ground."

Lone Star Ping

A big Texas bump to that.

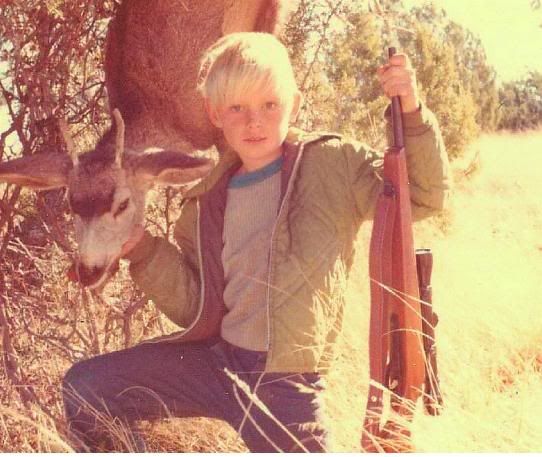

Alpine, Texas 1971

I love to see that shine in a boy's eyes when he kills his first deer!

I killed my first at eight, and I'll bet I looked just like that!

Alpine, huh? That's mulie country! Good show, gunner!

Walt Whitman wrote a moving poem about the massacre.

Danged if I can't help getting excited every time.

I'm thankful every day that I was born a Texan and taught

to shoot early & often. You never know when that might come in handy.

One thing puzzles me. I once read a list (I don't have it now) of the names of the men who died defending the Alamo (some names are lost). I'm sure that a good many more than three of the names were Hispanic.

Bump to read later. Thanks for the thread!

I shall never surrender nor retreat: then I call on you, in the name of liberty, of patriotism, and of every thing dear to the American character, to come to our aid, with all possible despatch.

I never noticed that before. He didn't say "Texan" character, he said "American." That's significant, although I couldn't begin to tell why.

Here's some food for thought, though. It took a certain kind of man (and woman) to brave the harsh frontier & the Indians to come to Texas in the early 1800s. It was full of outlaws, rattlesnakes, and Indians who didn't take kindly to people encroaching on their land. I guess the Texans inherited their frontier spirit from their late-1700s, Revolutionary/Patriot ancestors, and it eventually morphed into the uniquely Texan bravado spirit that it is today.

See, Pardek? It all originated from you Yankees, so now you can stop rolling your eyes (although I'll acknowledge it must be nauseating to people who don't understand it). :-)

A lot of the early comers to Texas had lived or grown up on the edge of things in the Carolinas, Kentucky, and Tennessee...a lot the characteristics that went into those people made up a lot of the Texican character too...willingness to fight for home and hearth, and a lack of fear about living on the edge to get a better life.

Austin's father had been one of the early American comers to Spanish Illinois, (soon to be Missouri), a man with foresight and the desire to make something of the American wilderness. He and several others attempted to found a bank to aid in the growing business in St. Louis...wonder what would have happened to American history if his bank hadn't foundered and he went to plan two, set up a colony of Americans in Texas?

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.