Posted on 10/06/2004 2:39:56 PM PDT by vannrox

WINGED CATS - WHAT ARE THEY?

Over the years there have been reports of winged cats, some of whom flapped their wings. Is this a new mutation of cats allowing them to take to the air after feathered prey or does the answer lie in poor grooming or an uncommon hereditary condition affecting the skin? As with the mythical "cabbit" (half-cat-half-rabbit) many would like to believe in winged cats which can fly. There are many authentic cases on file of cats with furry wing-like appendages, and in some cases the ability to move their wings, but as with so many freaks of nature, the reality is medical rather than mystical.

Please note that this is not, as some blogs suggest, a fake site along the line of Bonsai Kittens. The condition is called "Feline Cutaneous Asthenia" and is related to similar "elastic skin" conditions in humans (Ehler-Danlos Syndrome) and other animals. The human form of this condition is described at the end of this article. This condition is documented in veterinary journals (do a search on the web for "Cutaneous Asthenia" or "Ehler-Danlos Syndrome" if you are still dubious). The impression of "wings" can also occur due to matted fur in Persians and other longhaired breeds. Viewers of the popular "Animal Hospital" series in the UK will have seen several cases of this (e.g. "Shaun" the badly matted silver Persian).

REPORTS OF WINGED CATS

There are around 138 reported sightings of winged cats, 28 of which are documented cases (i.e. physical evidence exists). There are at least 20 photographs and one video. There has also been at least one stuffed winged cat, but accounts are suggestive of a Victorian fake. The number of documented cases is likely to rise, not because of an increase in occurrences, but because of advances in veterinary medicine and greater interest in the phenomenon.

Possibly the earliest report of a winged cat is the one Henry David Thoreau wrote about "A few years before I lived in the woods there was what was called a 'winged cat' in one of the farm-houses in Lincoln nearest the pond, Mr. Gillian Baker's. When I called to see her in June, 1842, she was gone a-hunting in the woods, as was her wont ... but her mistress told me that she came into the neighbourhood a little more than a year before, in April, and was finally taken into their house; that she was of a dark brownish-grey colour, with a white spot on her throat, and white feet, and had a large bushy tail like a fox; that in the winter the fur grew thick and flattened out along her sides, forming strips ten or twelve inches long by two and a half wide, and under her chin like a muff, the upper side loose, the under matted like felt, and in the spring these appendages dropped off. They gave me a pair of her 'wings,' which I keep still. There is no appearance of a membrane about them. Some thought it was part flying squirrel or some other wild animal, which is not impossible, for, according to naturalists, prolific hybrids have been produced by the union of the marten and the domestic cat. This would have been the right kind of cat for me to keep, if I had kept any; for why should not a poet's cat be winged as well as his horse? "

An undated, but old, winged cat can be found in the Niagara Valey as a stuffed and mounted specimen with bony structures near its shoulder blades covered with flaps of skin. The specimen looked genuine, but quite what the bony structures are is unknown (possibly extra limbs). An undated case from the 1800s involved a winged cat at the centre of a custody dispute with one party claiming him to be their cat, Thomas, and the other claiming it to be their feline, Bessy.

Another very early report was gleaned by cryptozoologist Karl Shuker from an odd report from India in 1868 although it is not possible to make a positive identification.. The report described a nondescript animal, said to be a flying cat. The Bhells called it pauca billee. The creature was shot by Mr Alexander Gibson, in the Punch Mehali and its dried skin was exhibited at a meeting of the Bombay Asiatic Society. The skin measured 18 inches (44 cm) in length, and was quite as broad when extended in the air. Mr Gibson, who was well known as a member of the Asiatic Society and a contributor to its journal, believed the animal to be a cat, and not a bat or a flying-fox as other people contended.

Almost thirty years later in August 1894, a report of a winged cat appeared in the Independent Press. A live cat with wings resembling those of a duckling was being exhibited in the neighbourhood by Mr David Badcock of the Ship Inn, Reach, Cambridgeshire, England. The year old cat had only revealed its wings after being somewhat roughly handled. The owner was charging 2 pennies for callers in the daytime to see his winged cat and had begun to take it around neighbouring villages in the evening. Several days later, the Cambridge Weekly News carried a similar account, presumably of the same cat. A sceptic had apparently asked the paper for further details about the winged cat which flew about in the village of Reach, near Peterborough and had suggested that there had been a good reason for the cat to hide its wings for 12 months, only unfolding them when gooseberries were ripening! The paper advised him not to make light of cats since creatures that are as much at home on the roof as in the cellar and that are never reached by stones, bullets, bootjacks or water thrown out of the window, could well be the winged cat of Reach in disguise! At the same time as the second report Independent Press reported that the "remarkable cat" had been stolen, but it was hoped that the perpetrators would soon by apprehended as the cat had apparently been traced to Liverpool, England. It is possible that the cat had shed its wings, leaving its owner somewhat embarrassed.

In 1897 a winged feline was discovered in Matlock, Derbyshire and was described in a local newspaper as ‘an extraordinary large tortoiseshell tom cat with fully grown pheasant’s wings projecting from each side of its fourth ribs'. According to eyewitnesses state the cat used its outstretched wings to increase its speed as it ran. The story was reported in the High Peak News of Saturday 26 June 1897:

Extraordinary Capture at Winster: A Tomcat With Wings.

The most interesting item in natural history, so far as the Matlock district is concerned, transpired this morning (Friday). Our reporter learns that Mr Roper of Winster, while on Brown Edge near that village, shot what he thought to be a fox, which had been seen in the locality some time previously, on Mr Foxlow’s land. Thinking he had missed his aim, Mr Roper gave up the quest, but returning later he found he had killed the animal. It proved to be an extraordinarily large tomcat, tortoiseshell in colour with fur two and a half inches long, with the remarkable addition of fully-grown pheasant wings projecting from each side of its fourth rib.

Unfortunately, the climate having been so excessively hot, the animal was allowed to putrefy, and after being generally exhibited all round the district the carcase has now been interred. It was seen by Mr Joseph Hardy and ample witnesses, so that there is no doubt the museums have missed a most curious animal. Never has its like been seen before, and eye-witnesses state that when running the animal used its wings outstretched to help it over the surface of the ground, which it covered at a tremendous pace.’

If it was genuine, the cat would have been unique for two reasons - its ‘pheasant’s wings’ and the fact that male tortoiseshell cats are extremely rare. In 1899, London's Strand Magazine contained a report of a ‘winged cat’ or kitten belonging to a woman living in Wiveliscombe, Somerset, England. A photo accompanied a short item in the November issue of Strand Magazine, whimsically entitled "Can a Cat Fly?". The cat was normal in every way, except for two fur-covered growths sprouting from either side of its mid-back. These flapped about like the wings of a scurrying chicken whenever the cat moved. The Wiveliscombe kitten was able to lift up its wings.

In 1933 or 1934 (dates vary), a winged black and white cat was captured in the garden of a private house in Oxford, England. A Mrs Hughes Griffiths found the cat in her stables during the evening of 9th June, 1934. She saw it unfurled a pair of long black wings sprouting just in front of its hindquarters and jump on to a beam. She described the distance as ‘considerable’ but apparently did not think of measuring it. Although cats can leap large distances, Mrs Griffiths did not think it could have leaped the distance unaided and claimed it had used its wings in a manner similar to a bird, she said. Mrs Hughes phoned Oxford Zoo for assistance and the zoo's curator W E Sawyer and managing director Frank Owen arrived with a net. The two men captured Mrs Hughes’ winged cat, and took it back to the zoo, where it was displayed for some while. Its wings were 6 in (15 cm) long. (The piece of cord visible in the photo is a leash.)

In 1936, a winged cat was found on a farm near Portpatrick, Wigtownshire, Scotland. From all accounts it was a very odd looking cat. It was described as a white longhair with one blue and one red eye. Its wings were flaps 6 in (15 cm) long and 3 in (7.5 cm) wide on its back and were said to rise when the cat ran and ‘fold down into her side’ when she rested. This is consistent with the behaviour of large mats of fur or loose flaps of skin which would rise or flap about when the cat was in motion, but rest hanging down under their own weight when the cat stood still.

In 1939, a black and white winged cat from Attercliffe, Sheffield, England, was sold by its owner, Mrs M Roebuck, to a Blackpool museum of freaks. Sally, actually a black-and-white male cat boasted a 2 ft wingspan and wings which could be actively raised above his body. According to Mrs Roebuck, Sally used his wings to assist him in making lengthy leaps through the air.

During the Second World War, a large, overweight black-and-white cat in Ashford, Middlesex was a local attraction because of the wings which sprouted from its shoulders. The cat was owned by two pensioners and people would peer over the wall into their garden for a glimpse of the winged cat.

In 1950, a winged tortoiseshell cat called Sandy became star attraction at a carnival in Sutton, Nottinghamshire. Sandy was an adult cat but unaccountably grew a sizeable pair of wings and was loaned to the carnival by her owners. Such was her impact, that she was fondly remembered many years later by local people. Since there were no previous reports of Sandy growing wings, this sounds like a case of matted fur.

Winged cats are not confined to the UK. The largest recorded feline ‘wing-span’ is 23 inches (58.4 cm). This was a 24 inch (60.9 cm) long, 20 lb (9.07 kg) winged cat shot dead in northern Sweden in June 1949. It had allegedly swooped down on a child before being shot. The body was given to the local museum. A winged cat which was shot and killed in Northern Sweden was said to have hindquarters covered in feathers, although an earlier report from Professor Rendahl of the State Museum of Natural History made no mention of this, saying merely that the wings were a deformity of the skin which happened to take the shape of wings.

In May 1950, Madrid porter Juan Priego's grey Angora cat, "Angolina", made newspaper headlines throughout the Spanish capital due to her pair of large fluffy wings (the date of mid-1959 is also given for Angolina). Several winged cats have been reported from the USA. One was caught near Pinesville, West Virginia in May 1959. Teenager Douglas Shelton found the Persian cat (which he named Thomas) and he and the cat became instant celebrities. Following a TV appearance, a local woman, Mrs Charles Hicks, began legal proceedings against him to reclaim her lost cat, Mitzi. When the cat was produced in court, she was wingless, having shed her wings two months after Shelton had found her. The "ings" had been kept and were seen to be no more than extensive mats of fur which had eventually fallen away from the body. At that point Mrs Hicks claimed the cat was not hers after all! I have seen similar extensive mats of fur on unkempt longhaired cats during cat rescue work.

The matted fur hypothesis is borne out by a case from Alfred, Ontario, Canada in 1966. A winged cat said to be swooping down on farm animals and attacking other cats was shot dead and buried but was exhumed several days later for examination by scientists at Kemptville Agricultural School. Their conclusion was that the cat’s "wings" were nothing more than matted fur. The cat was also found to have had rabies which would account for its strange behaviour. Many, if not all, of history’s winged cats seem to have been longhaired which suggests that matting fur accounts for some, if not all, sightings.

In the October/November 1967 issue of "The Cat", Cecily Waddon wrote "May I appeal to anyone thinking of having a cat, not to choose a long haired one unless they are prepared to spend about ten minutes a day on grooming throughout the cat's life? I recently had brought to me one with fur not only matted solid all over its body, but with felt-like wings the size of my hand, growing outwards." The two photos here show a Persian with the beginnings of "wings" caused by felt-like lumps of matted fur. When the cat moved, the wings did indeed flap!

In 1970, J A Sandford of Wallingford, Connecticut saw a winged cat in a neighbour's garden. The orange-and-white longhaired cat was "positively waddling due to large wing-like growths hanging from its midsection". The owner explained that this was the way that cats shed their fur in summer and Sandford noted that the fur was indeed matted forming rectangular pads about 5 inches long by 4 inches wide. Although Shuker describes this as a textbook example of Feline Cutaneous Asthenia (see next section), it is in fact a textbook case of a badly matted longhair cat and such cases are regularly seen by vets and described by Ms Waddon in 1967. I personally have seen mats the size of a small kitten form on longhaired feral cats and this causes them to waddle exactly as Sandford describes. Any Persian owner will tell you just how quickly a longhaired cat's fur forms into felted mats if left ungroomed. By contrast, in Feline Cutaneous Asthenia, skin and connective tissue are also involved in the wings.

In 1975 the Manchester Evening News published a photograph of a winged cat which had lived in Banister Walton & Co builder's yard at Trafford Park, Manchester, England during the 1960s. The cat had a pair of long fluffy wings (11 inches/29 cm)projecting from its back and the skin of its tail had flattened into a broad flap. According to some of the men working in the yard at that time, the cat could even raise its wings above its body, suggesting a deformity which contained muscle as well as flaps of skin. In 1986 a winged cat was noted in Anglesey, Wales and later moulted its wings. In April 1995, Martin Millner spotted a fluffy winged tabby in Backbarrow, Cumbria, England.

In 1986 a winged cat was reported in Anglesey, UK, and shortly after being photographed it shed the wings - suggesting they were mats of fur. Throughout the 1990s, I became accustomed to seeing a winged black-and-white longhaired feral cat called "Dorothy". The wings were extensive mats of felted fur which formed in spring and summer. The largest mats extended from shoulder almost to hip and flapped as the cat ran. These "wings" were eventually shed naturally and some shed mats were found to be the size of a small kitten. When possible, Dorothy was trapped, anaesthetised and dematted as the mats were cumbersome and undoubtedly uncomfortable.

In 1998, a black winged cat was to be found in Northwood, Middlesex. The wings were 2-3 inches back from the shoulder blades about 8 inches long, 4 inches wide and an inch thick. They flapped as the cat ran.

At Bukreyevk (near Kursk), Central Russia, a winged cat was killed by superstitious villagers in 2004. According to the local Komsomolskaya Pravda newspaper locals drowned the deformed cat after believing it was a messenger of Satan. The stray cat had entered the yard of Nadezhda Medvedeva. She said it stood up and "just like a chicken" stretched out two wings. This made her hair stand on end and local people were in no doubt that the cat was a messenger of the devil. Medvedeva had initially heard a soft meowing and poured some milk into a bowl. The cat - a ginger tom cat "twice as big as normal" drank greedily meowed for more. She continued to feed the stray, but after a couple of days her daughter became scared, claiming the cat had wings. Nadezhda Medvedeva observed the cat slowly move its wings just like a chicken. She immediately concluded her visitor was some sort of demon. However the daughter had already named the cat Vaska and claimed he was affectionate and had obviously been someone's pet. The rumour of the winged cat soon reached Kursk, but by the time a reporter heard it and reached the village, the unfortunate cat had been drowned by a local drunk. A sack contianing the cat's body was later recovered from a pond near the Medvedev’s home. Although decomposition had already set in, the reporter from the local Komsomol newspaper confirmed the cat did actually have wings. There are no reports of the body being sent for further analysis to determine what the wings were. The Russian news article was illustrated with a grainy copy of the Manchester winged cat from the 1960s.

WHAT CAUSES WINGED CATS?

The wings on these creatures have several possible causes. Firstly they may be extensive mats of fur which hang from the cat until the whole mat falls away. I have seen this happen in stray and feral longhaired cats in Chelmsford, Essex, England. The large mats hang from the cats' sides in wide, flat sections until the fur holding them in place is moulted away or the mat is pulled away by becoming caught on thorns. When the cats run, the mats flap about uncontrollably. The fact that many of the reported winged cats were longhairs suggests that matted fur accounts for a proportion of cases.

|

Longhaired cat starting to develop a wing-like mat. |

A possible, but less likely, cause is that the fur-covered wings may have been congenital deformities such as vestigial legs (as found in some forms of conjoined twins), useless for any purpose at all, including flying. Conjoined twins occur when a fertilised egg splits incompletely into 2 parts; this results in anything from two cats joined by a band of tissue, to two cats sharing 6 legs between them, to a single cat with two faces or a cat with extra limbs. An extra pair of forelegs dangling from the shoulders but which remained rudimentary could give the impression of wings and might even "paddle" as the cat ran. Conjoined twins are too rare to account for all sightings of winged cats.

Where matting is not the cause, the most likely explanation is a deformity of the skin which just happens to take the shape of wing-like folds of skin sprouting from the cat's back or shoulders. The cat has little or no control over its "wings" and certainly cannot flap them, fly or swoop down from above! In the 1990s, cryptozoologists (people who try to trace mysterious creatures) and veterinarians realised that an obscure genetically based skin disorder provided the answer to many cases of winged cats. A rare hereditary medical condition called Feline Cutaneous Asthenia (FCA) causes the skin on the cat's shoulders, back, and haunches to be abnormally elastic. Even stroking the skin can cause it to stretch. The stretching skin forms pendulous folds or flaps which sometimes contain muscle fibres, enabling them to be moved. They cannot be flapped like a bird's wing since the flaps do not contain any supporting bones nor any joints.

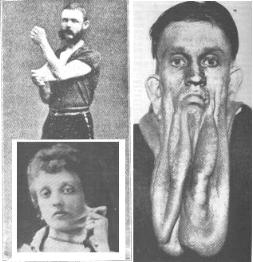

Cutaneous Asthenia literally means "weak skin" and refers to the fragility of the skin. It is also called "dermatoproxy" and "hereditary skin fragility". There are similar conditions in humans, dogs, mink, horses, cattle and sheep. In cattle and sheep the term "dermatosparaxis" ("torn skin") is used. In horses a similar condition is called "collagen dysplasia". It is also known as "cutis elastica" ("elastic skin"). The human form is called Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) and occurs in several different forms. Elastic-skinned people have exhibited themselves at freak shows, demonstrating the condition by stretching handfuls of their hyperextensible skin away from their bodies. Probable human sufferers include Arthur Loose the "Rubber Skinned Man" whose cheeks and jowls hung in pendulous folds 8 inches (20 cm) long and James Morris the original "India Rubber Man" who could pull his elastic skin 18 inches (44 cm) from his body.

As the term dermatosparaxis implies, the skin is also abnormally fragile. It tears at the slightest contact with anything sharp - rough surfaces or even the cat’s own claws when scratching or grooming itself. Like the rest of the cat's skin, the wing-like projections are covered in fur . If they incorporate sufficient muscle fibres, they can be raised up and down as in the case of the Trafford Park cat, An interesting aspect of this condition is that the flaps of skin peel off very easily, usually without causing bleeding. This could explain some of the reports of winged cats who suddenly "moulted" their wings, but whose mats were not due to matted fur. The pieces of stretched skin simply slough off.

In mammals, the skin comprises two principal layers. The surface (outermost) layer is the epidermis and is relatively thin. Below the epidermis is the dermis which is thicker and contains connective tissue. The dermis provides support and packing as well as containing nerves and blood vessels. The dermis consists largely of fibres made mostly of a protein called collagen. Collagen binds the cells of the dermis together. Mammals with Cutaneous Asthenia have defective collagen in certain areas of the skin, this makes it incapable of functioning effectively as tissue packing. As a result, the is extremely flexible and fragile in the affected areas. Most usually affected areas are the shoulders, back and haunches and the stretching gives the appearance of wings sprouting from these areas. Where the defect occurs in regions containing sufficient musculature so that muscle is included in the flaps of skin, the wings can even be moved slightly, providing an explanation for the reports of cats able to lift or move their wings. Even where the wings don't contain any muscle, they would naturally bounce up and down as the cat ran, giving the impression of flapping.

Feline Cutaneous Asthenia remains an obscure and little-studied condition. There are still only a few cases recorded in veterinary publications although awareness of, and interest in, this condition appears to be growing, particularly as we gain greater knowledge of genetics and gene-mapping. A recessive autosomic (non-sex linked) variant feline cutaneous asthenia has been discovered in Siamese cats and in breeds with Siamese ancestry; in the homozygous state is is apparently lethal.

VETERINARY REPORTS OF WINGED CATS

In 1970, Peter Pitchie, a vet in Kent, England, received a 5 month old female tabby cat for spaying. When he attempted to inject an anaesthetic, the cat's skin immediately split. When he shaved the cat's flank for the spaying incision (flank spaying is usual in the UK) the skin split again. Yet more splits occurred when he tried to sew up the first two. He eventually succeeded in suturing all the splits using a round-bodied needle and despite their dramatic formation, however, they all healed in a straightforward manner.

In 1974, a 4 year-old tom cat, known by the owner to have "fragile skin", was taken to Cornell University’s New York State Veterinary College Small Animal Clinic. Dr DV Scott noted that its skin was exceptionally thin and velvety in texture. The velvety texture is typical of the condition in cats. The skin was hyperextensible (extremely stretchy) and there was a criss-cross network of fine white scars where previous tears had healed. When some fur was clipped from one foreleg so that the vet could take a blood sample, the skin immediately peeled away. This peeling was seen to occur whenever the slightest pressure was applied anywhere to the cat’s skin. Investigation showed that the collagen fibres in the cat's skin were abnormal.

In 1975, an adult female cat examined by W.F. Butler of Bristol University’s Anatomy Department was found to have very fragile skin on its body. Studies showed it to have abnormally low levels of collagen in the skin of its lower back. At this time, the genetic nature of skin hyperextensibility and fragility in the cat, and its link to reports of winged cats, was not known.

In 1977, Drs Donald F. Patterson and Ronald R. Minor of the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Veterinary Medicine studied a young tomcat with short grey hair. The cat severely lacerated its skin simply by scratching itself. The skin was found to be delicate and tore easily. It was also extraordinarily elastic and when the fur on the cat's back was gently lifted, it could be extended to a distance above the backbone equal to about 22% of the cat's entire body length! The two vets wrote a paper on the subject and photographs of the cat with the skin gently stretched showed a classic winged cat, identical to those in reported sightings. Because of the difficulties in caring for a cat with an incurable skin fragility problem, the cat’s owner donated her pet to the veterinary school. It was mated to 4 long-haired female cats and several of the offspring inherited the condition.

There is an additional (undated) veterinary report of a 6 month old non-pedigree tom cat which was taken to the vet with two skin wounds on the right hand side of its body. The skin in the affected areas, and the skin on the cat's back, was hyperextensible, smooth and easily torn by just a small amount of pressure. Skin samples were examined under the microscope and revealed abnormally low levels of connective tissue.

Winged cats were being recorded as long ago as the 1890s and perhaps even earlier. A skin condition causing fragile, stretchy skin in cats had been investigated and documented since the 1970s. But up until the 1990s, no-one had made the connection between winged cats and Feline Cutaneous Asthenia in spite of the 1977 photo in Drs Patterson's and Minor's veterinary paper. This is not entirely surprising. Cryptozoologists and others who research mythical creatures may not have access to, or interest in, veterinary journals about medical or hereditary conditions. Veterinarians are more interested in the creatures they are likely to encounter in the clinic than in reports of mythical beasts which appear mainly in magazines relating to paranormal phenomena.

Hence none of the winged cats recorded in magazines about strange phenomena had been documented in the veterinary literature. None of the recorded veterinary cases of Feline Cutaneous Asthenia had been featured in publications about strange phenomena. Researchers with an interest in medical anomalies, freakish individuals and genetic conditions finally made the link.

MORE ABOUT THE DISORDER

The term collagen dysplasia is used for Feline Cutaneous Asthenia and related conditions in other animals. These conditions comprise a complex group of disorders of the connective-tissue in the skin. The affected tissue has reduced tensile strength. We report here the case of a crossbred male cat, aged 6 months, that presented with two skin wounds in the region of the right thorax and right iliac tuberosity. The skin of these regions and of the animal's back was hyperextensible, smooth to the touch, and easily torn with minor trauma. Microscopic examination of skin samples revealed reduced dermal connective tissue consisting of shortened and fragmented collagen fibres. Normal fibres were intermingled with altered fibres. Ultrastructural changes in collagen fibres included disorientation of fibrils within the same bundle, marked spacing differences, and variation in the diameter of transverse sections. The fibrils maintained the transverse striations characteristic of normal collagen.

The tom cat investigated by Cornell University’s New York State Veterinary College was found to have abnormal collagen fibres in its skin. The fibres were fragmented, irregular and disoriented, with very few normal fibres present. The female cat examined at Bristol University was found to have very low levels of collagen in the dermis of its lower back. The tomcat donated to the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Veterinary Medicine not only had abnormal connective tissue, but passed the condition on to some of its offspring when mated with 4 different females. Those matings demonstrated that Feline Cutaneous Asthenia was inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. This means it is not linked to the gender of the kittens (haemophilia in humans is an example of a sex-linked trait) so males and females are equally likely to inherit the trait. Studies showed that all of the affected kittens showed packing defects in their dermis collagen.

Skin samples from an affected 6 month old non-pedigree tomcat were examined under the microscope and revealed a reduced amount of connective tissue. The collagen fibres were shorter than they should be or were fragmented. There were some normal fibres mixed in with the abnormal fibres. A more detailed examination of the individual collagen fibres showed that the fibrils (strands, a bit like the strands in a piece of rope) were irregularly sized and irregularly spaced. If you visualise an abnormal fibre as a frayed section of rope and the normal fibre as a new section of rope, you get an idea of why the abnormal ones tear more easily.

The group of disorders characterised by fragile, excessively stretchy skin are known as collagen dysplasias and, as previously stated, these conditions are found in numerous species including humans. The condition is due to a defect in the connective tissue (made of collagen) in the skin and can be caused by decreased production of collagen or production of a normal amount of collagen, but the collagen itself is faulty and therefore weak (like a frayed rope). Because many different genes are involved in putting together of proteins and of skin, there may well be several different genes which cause outwardly identical symptoms. Modern genetic techniques might now allow feline geneticists to work out how many different types of Feline Cutaneous Asthenia there are.

The symptoms are excessively stretchy or elastic skin which tears easily though the tears usually do not bleed. The skin may be criss-crossed with scars where tears have healed. Lacerations can be caused by something as simple as the cat scratching itself, brushing against a rough surface or even by an injection needle. Flaps or folds of loose or stretched skin may appear, resembling wings. These are thin, easily torn and usually bleed very little when damaged. Depending on the severity and exact cause of the condition, small tears may heal rapidly leaving irregular white scars or the tears may enlarge and form large wounds. Flaps of loose skin ("wings") are often shed without apparent damage to the cat. Some forms of the condition also affect the blood vessels in the skin and may cause bruising and large blood blisters. In dogs, a similar condition appears to be linked to looseness in the joints and to abnormalities of the eye (slipped lens or cataracts).

It is usually easy to recognise this condition, due to a young cat suffering excessive and unexplained skin damage or damaging itself through scratching or through play-fighting (or real fighting) with other cats.

LIVING WITH FELINE CUTANEOUS ASTHENIA

In early reports of winged cats, the owners frequently exhibited the cats as freaks or donated them to zoos or museums. You might think that owning a winged cat is a way to make money. If the wings are due to matted hair then they will eventually be shed - and an expert examination will have detected the cause and debunked the winged cat as a neglected cat. You are more likely to face cruelty charges (for cruelty through neglect) than to make any money! If the cause of the wings is Feline Cutaneous Asthenia, you are faced with caring for a cat with all the normal feline behaviours, but with abnormally fragile skin. This leads to high veterinary bills as any cuts and tears are treated and it makes routine treatments such as neutering, microchipping or vaccination hazardous. Even wearing a collar or walking harness could cause lacerations. The lacerations provide an entry point for bacterial, viral and fungal infections. Although the life expectancy appears to be normal, many affected animals are euthanised due the extensive and expensive care and attention that will be required throughout its life.

If you are a breeder, the affected cat must not be bred or it will pass on the trait. If neither of the parents has the condition then it is probably due to recessive (hidden) genes and both parents and all of their offspring are potential carriers - none of them should be bred because the trait will probably resurface several generations later.

If you have a winged cat, rather than exhibiting it, you will need to modify its lifestyle and environment to minimise the damage its fragile skin suffers. Cats with Feline Cutaneous Asthenia can live a full life if the owner is careful and not squeamish about dealing with the inevitable lacerations and possible infections. Activities likely to cause mild trauma must be avoided; this includes playing with other cats, climbing trees, going through undergrowth or any activity which could bring it into contact with rough surfaces or sharp objects. You will need to remove or pad (with foam) any rough or sharp corners and objects in your home, possibly confining your cat to certain areas which can be made safe for it. Its resting places must be well-padded.

If your cat suffers the form of the condition where tears enlarge or skin folds tear away, prompt veterinary attention is necessary to suture or glue any small wounds before they enlarge or become infected. Skin glues or liquid bandages (or spray-on skin) are expensive but avoid stitches. The vet must also treat any other skin conditions, including skin parasites, which may cause your cat to scratch. Flea control is absolutely essential as flea bites will cause the cat to scratch.

In this instance, declawing of all four paws should be considered on medical grounds - since your cat must live indoors, it may also be safer without claws. If declawing is anathema to you, then rubber claw-caps such as SoftPaws might work. In order to prevent self-mutilation and to protect the skin against environmental dangers, the cat might have to wear clothes - either baby clothes or a specially tailored suit made of stretchy swimsuit fabric and with seams on the outside to prevent abrasions.

You cannot scruff a cat with Feline Cutaneous Asthenia as you are likely to end up with a handful of skin, fur and even flesh where the scruff tears away completely. You must also watch out for joint luxation (slipping joints, such as hip dysplasia) which often occurs as part of the syndrome. Because the body has to do so much more healing of what would be minor scratches in other cats, the affected cat will probably need vitamin supplements to promote skin growth, anti-inflammatory drugs to combat certain skin conditions and antibiotic treatments.

TAXIDERMY FAKE WINGED CATS

In the 21st century, better grooming and better medical care can prevent "wings" from forming in the first place. Afflicted cats are more likely to go to a veterinary clinic than be exhibited by the owner. The likelihood that the wings will be shed or surgically repaired makes genuine stuffed and mounted winged cats unlikely. The skin fragility related to cutaneous asthenia presents a problem to taxidermists. There is one report of a preserved allegedly genuine winged cat.

Taxidermy fakes, known as "grifts" or "gaffs" (both words which mean "to swindle or deceive") , are made by combining parts from different creatures. Some were made purely to entertain the public while others were passed off to collectors as "genuine" creatures (usually mythical creatures). Many have appeared in sideshows and curio cabinets. A common example is the "mermaid" made from a monkey upper body attached to the body and tail of a large fish. Such was the trade in these fakes, that the first platypus specimens were dismissed as fakes made by skilled taxidermists.

A few people still make taxidermy fakes as a form of art. Winged cats and kittens can be made using a cat's or kitten's body and the wings of a suitably sized and similarly coloured bird. Although the idea is distasteful to many cat-lovers, I checked with a British taxidermist who confirmed (with respect to non-food animals) that he only uses bodies of animals which have died, or been put to sleep, due to age, illness or accident; this is to ensure that animals are not killed simply to provide material for the taxidermist's art.

There have also been a few cases of people attaching birds' wings to living cats using wire or string, but these are generally quickly removed by the cat!

WINGED CATS THROUGH THE AGES

Regardless of the medical causes, winged cats have caught the public imagination over the years.

There is even a tale of a winged big cat known as the Cat-a-Mountain. The explorer Marco Polo reported the existence of a large predatory cat in the Far East with the body of a leopard but a strange skin that stretched out when it hunted, enabling it to fly in the pursuit of its prey. It is highly unlikely that a lion or similarly sized cat could survive with the Feline Cutaneous Asthenia condition so the Cat-a-Mountain is most likely an imagined hybrid a big cat and a large bat or a big cat and a flying squirrel (which has flaps of skin enabling it to glide). Later authors used the term to describe a wild cat and by the seventeenth century it had been abbreviated to Catamount and was used as a synonym for the American Mountain Lion (Cougar, Puma).

The winged cats of myth and legend were often demonic creatures with "feathered" wings and liable to swoop down on humans. Cats were all too often associated with the devil hence there were evil bat-winged cats in superstition. Below is a detail from a Kircher engraving (1667) depicting a curious mix of cat's head, bat's wings and human torso. The later picture, by Grandville in the 19th Century is an anthropomorphic image of cats in the forms of angel, demon and humanised cat. It is the angelic image which seems to have persisted into modern times, while the image of bat-winged demonic cats has been consigned to history.

|

|

|

As cats moved into the home and became our companions, the popular image of winged cats also began to change (as illustrated by Grandville). Most modern winged cats are either cute and fuzzy storybook creatures (Pegapuss); feline analogues of angels or fairy-like creatures.

|

"Pegapuss" |

"Flittens" by Greenwich Workshop |

"Almost Purr-fect Angels" by Bradford Edition |

In the 1980s and 1990s, a popular range of fantasy novels depicted shy owl-winged cats which were the pets of wizards and which were a magical hybrid of cat and owl. The winged cat motif remains common in fantasy role-play games. Figurines, Christmas tree decorations and pendants of winged angel cats have become popular. Angel kitty figurines are especially popular among bereaved cat owners and feature cats with feathered wings in much the same style as human angels.

Examples of modern winged cats (2000s) can be found in Greenwich Workshop's range of winged kitten figurines called "flittens" (flying kittens) which were whimsical kitten-fairies with colourful butterfly wings and Bradford Editions' "Almost Purr-fect Angels".

The rise in popularity of pet cats has led not only to medical diagnoses and better understanding of the mysterious winged cat condition, but also to a change in the way fictional winged cats are portrayed.

HUMAN CUTANEOUS ASTHENIA

There are a number of cases of human cutaneous asthenia described in medical texts. The following is adapted from "Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine" written in 1896 by George M Gould & Walter L Pyle.

"Abnormal Elasticity of the Skin. In some instances the skin is affixed so loosely to the underlying tissues and is possessed of so great elasticity that it can be stretched almost to the same extent as India rubber. There have been individuals who could take the skin of the forehead and pull it down over the nose, or raise the skin of the neck over the mouth. They also occasionally have an associate muscular development in the subcutaneous tissues similar to the panniculus adiposus of quadrupeds, giving them preternatural motile power over the skin. The man recently exhibited under the title of the “Elastic-Skin Man” was an example of this anomaly. The first of this class of exhibitionists was seen in Buda-Pesth some years since and possessed great elasticity in the skin of his whole body; even his nose could be stretched. [The bearded man] represents a photograph of an exhibitionist named Felix Wehrle, who besides having the power to stretch his skin could readily bend his fingers backward and forward. The photograph was taken in January, 1888.

"Abnormal Elasticity of the Skin. In some instances the skin is affixed so loosely to the underlying tissues and is possessed of so great elasticity that it can be stretched almost to the same extent as India rubber. There have been individuals who could take the skin of the forehead and pull it down over the nose, or raise the skin of the neck over the mouth. They also occasionally have an associate muscular development in the subcutaneous tissues similar to the panniculus adiposus of quadrupeds, giving them preternatural motile power over the skin. The man recently exhibited under the title of the “Elastic-Skin Man” was an example of this anomaly. The first of this class of exhibitionists was seen in Buda-Pesth some years since and possessed great elasticity in the skin of his whole body; even his nose could be stretched. [The bearded man] represents a photograph of an exhibitionist named Felix Wehrle, who besides having the power to stretch his skin could readily bend his fingers backward and forward. The photograph was taken in January, 1888.

In these congenital cases there is loose attachment of the skin without hypertrophy, to which the term dermatolysis is restricted by Croeker, Job van Meekren, the celebrated Dutch physician of the seventeenth century, states that in 1657 a Spaniard, Georgius Albes, is reported to have been able to draw the skin of the left pectoral region to the left ear, or the skin under the face over the chin to the vertex. The skin over the knee could be extended half a yard, and when it retracted to its normal position it was not in folds. Seiffert examined a case of this nature in a young man of nineteen, and, contrary to Kopp’s supposition, found that in some skin from over the left second rib the elastic fibres were quite normal, but there was transformation of the connective tissue of the dermis into an unformed tissue like a myxoma, with total disappearance of the connective-tissue bundles. Laxity of the skin after distention is often seen in multipara, both in the breasts and in the abdominal walls, and also from obesity, but in all such cases the skin falls in folds, and does not have a normal appearance like that of the true 'elastic-skin man'.”

OTHER CURIOSITIES AND CRYTOZOOLOGICAL CREATURES

read later

Wait. I don't get it. What's the punchline?

Is there an established hunting season, or are they considered as varmits? They are bound to be easier to hit than doves.

bttt

Here's a winged cat for you!

|

|

|

Ping.

Ping

Sorry...I don't like cats...and generally like cat-people even less...because every cat-person I know is a flaming liberal...ok, I feel better now!

(This is a real picture I took in front of my house a couple of months ago)

Why didn't you post some good cat recipes, also?

Kinda hard to scale the size of the bird in that shot. What was the wingspan?

My guess would be at least six feet.

Really? That's the size of an eagle, but the bird's "nose" is too pointed. Must be a hugh - er, huge - crow, I guess.

I think it's a turkey buzzard. They look like crows but are the size of eagles.

What this heck is the deal with this post? Admins should prevent this kind of crap from being posted - give FR a bad name.

---

Kitty Ping List alert!

[Freepmail me to get on or off the Kitty Ping List.]

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.