Posted on 09/16/2008 10:08:51 PM PDT by Ramius

Sword Post 2:

Woohoo! It’s time for Tuesday night Sword Pron!

Today’s topic: Guards.

“Guards” are essentially stances. They’re places to start and places to end. They are ways to hold the sword to begin fighting, and curiously enough, most of the strikes that one will take with a sword are merely a progression from one “guard” or “hut” to another.

To wit:

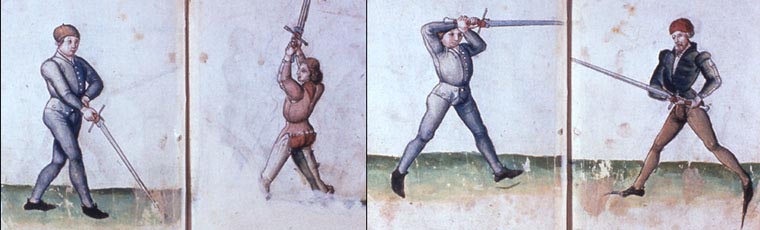

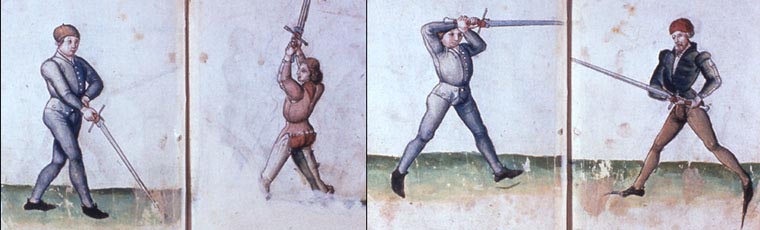

There are 4 basic guards. Since the vast majority of the surviving source material is in German, they are named in German. The picture is from a 14th century Fechtbuch (fight book). They are (in the order of the picture: “Alber” (fool), “Vom Tag” (from the roof), “Ochs” (Ox), and “Pflug” (plow). These were the four taught by master Leichtenauer in the 14th century. Leichtenauer is pretty much the reference standard for European Longsword. Later masters almost always referenced him as the first original source.

The guards are symmetric… that is… there are left foot forward and right foot forward, left or right hand analogues of each guard, with the sword on either the right or left side.

Alber

The fool. Called this, most think, because it baits the unknowing opponent into thinking that with the sword low they are open to an easy attack. Don’t get stuck on stupid. Alber is possibly one of the best defensive postures to take. And an awesome offensive posture too. One of my favorites. It’s a killer.

Vom Tag

From the Roof. This guard actually includes many variations of the “high” guard. It can be up over one shoulder, as well as being up high over the head. The essence of it is that the sword is cocked back overhead, usually over a shoulder. This is the most powerful place to start a downward strike. Of course.

Ochs

The Ox. A wonderfully versatile guard. I’ve found in practice and sparring that I end up in Ochs much of the time, and both left-hand and right-hand. There’s lots of good strikes that end up in Ochs, and lots of good strikes that start in Ochs. So… it’s a very useful place to be.

Pflug

The Plow. A middle guard with the sword pointed at the opponent. Hands near the hips and sword pointed up toward the opponent’s face. A natural starting place, but not a strong place to strike from, other than the lunge forward.

A fifth guard, not in Leichtenauer: Nebenhut.

The tail guard. An additional guard, found in later studies than Leichtenauer, but well preserved. This is a wonderfully useful guard. Many strikes end up in Nebenhut. It gives the illusion of vulnerability, like Alber, since the blade is back and pointed away from the adversary and yet it is a very powerful place to strike from, especially with the short-edge of the blade. There is a powerful Unterhau (under strike) and of course a powerful Oberhau (over strike) from this position.

Next, we’ll do a short class on Unterhau, Oberhau, and Meisterhau. (Under strikes, Over strikes, and Master strikes).

Preview: A “Meisterhau” is a “master stroke” and it is defined as being at once offensive and defensive at the same time. It is a strike that defends first.

Do you have a ping list? If so, could you add me?

Sword fighters unite! (we may need these skills:) ping me if you got one!

I am wondering if you are a member of the SCA...my son is very big into medieval history, including armoring (sp?), leatherworking, medieval martial arts, and just about everything medieval. I will have to email him your post.

He just returned a few weeks ago from an archaeological dig in Belgium. He spent four weeks at an old medieval castle ruin digging and just loved it.

A friend of his recently challenged me to a sword fight...duel I guess (SCA standards) because I made fun of his sword fighting technique which I now see is a legitimate defensive stance (overhead in your post). Seems to me to be limited in strike capability and also, this young man tends to lean back making him a bit off balance for striking at his opponents. That is how we got onto the challenge as I told him that even I as an old man (but who has experience in brawling) can beat him because I would know when he would begin his swing and have plenty of time to react to it...I am not quite so confident now that I see it is a legitimate style of fighting...I don’t really know anything about sword fighting, but will enjoy even getting pounded I am sure. Thanks for posting that information.

For tomorrow.

I have a small but treasured collection of ancient weaponry. If you have a pinglist it would be an honor to be included in it.

I, too would like to be added to any ping list you assemble on this topic.

I actually am in the SCA. If you have more in future, ping me, please.

Hmmm...I was always partial to Katanas myself.../shrugs

BTW, anyone know anything about WWII Japanses Officer Katanas??? I have one in a red case and one in a leather case that my Grandfather brought back from the Pacific with him.

Puchased or war trophies(personally captured)?

Standard issue is still fairly valuable but a family sword is in a whole different league.

Same as above, if you have a ping list please add me.

Very nice post. Can you link the first post?

Please add me to your ping list. I don’t own a blade longer than my Ontario RAT7, but this is fascinating.

Another for your ping list, if there is one.

ping

This is a re-post of something that I posted previously on another thread some time ago but it starts off the discussion of swords:

Sword Parts:

There are of course the familiar parts, from left to right on the picture, of Blade, Guard, Grip and Pommel. The Guard is also called the "Cross". Some refer to the Guard as the "Quillions", but that may refer specifically to guards made with fancy loops and hoops, decorations and such.

The Blade is further divided into the "weak" and the "strong". The weak part is that from the point about halfway back and the strong part is from halfway back to the Guard. This comes from the amount of leverage you can apply to the blade. If you bind or parry another sword on the "strong" part, naturally you have much more leverage than if you bind closer to your point. If you bind your strong against your opponent's weak, then you get to control where the swords go.

[language note: The word comes from the german "binden" meaning "to bind" which is when the two swords are in contact, often ending up with the guards locked forcefully. When this happens, a grappling match is about to break out or one of them is about to break the bind and strike decisively. Either way, somebody's about to die. One wonders if this isn't the origin of the expression "to really be in a bind" when one is in deep trouble.]

The blade also has a "long" (or "true") edge and "short" (or "false") edge. This terminology originated with curved swords like a saber or cutlass where one edge is actually longer than the other since it's on the outside of the curve. This terminology applies still to double-edged longswords with straight blades, even though both edges are obviously the same length. In this case it depends on how you're holding it and where your knuckles are. The edge that lines up with your knuckles is the "long" edge. This would be the primary striking edge for the basic downward strike you'd make from high to low. The short edge would be the other one, on the "back" of the blade, that is, the edge that lines up with the webbing of your thumbs.

The short edge is just as useful as the long edge, perhaps more. There are some sneaky underhanded tricks involving strikes with the short edge. More on that another day.

Every blade has an optimal spot on the edges to strike with, just like every baseball bat has a "sweet spot". This is the Center of Percussion (CoP). It's generally just several inches down from the tip. You can find this spot easily by holding the sword out in front of you with one hand, point up, edge-on, and hit the pommel with the heel of your free hand. The sword will vibrate visibly in your hand. There will be two "nodes" in the vibration that don't move. One will be (on a good sword) just at or above your hand no more than an inch or two out from the guard, and the other will be up several inches from the tip. That's the place to hit things. At that spot you get to take advantage of the natural harmonics of the blade, transferring little or no vibration back to your hands and more importantly, not wasting energy that's absorbed into the vibration of the blade. But that said, when you get a chance to cut-- you cut. The whole blade cuts just fine.

Many blades also have a deep groove down each side called a "fuller". In longswords this groove was generally narrow and about 1/2 to 3/4 the length of the blade. In Viking swords the fuller was usually wide, perhaps more than half the whole width of the blade and went all the way down just short of the tip.

Contrary to popular myth this is not a "blood groove" to let blood flow out of a wound more quickly. It doesn't work that way. The primary purpose is to make the blade lighter by removing steel. It also makes the blade stiffer, due to the round concave cross-section on each side. Not all longswords featured a fuller but had a diamond-shaped cross-section. Some had dual or triple fullers in parallel.

Another myth: Longswords were heavy and cumbersome. Not so. Most were only 2.5 to 3.5 lbs, not 10 or more as many people think. With two hands, a properly made one is amazingly lively, fast and nimble. That said, swinging one around for an hour or so-- with intent-- is a heck of a workout. But most sword fights didn't last very long... probably ten or fifteen seconds. Thirty seconds would be a long one.

Another myth: Armor made soldiers slow to move and unable to even get up if they fell down. Nonsense. Sure, chain mail or plate armor was heavy. But not that heavy. It was nothing compared to to what modern soldiers and Marines carry around every day. But more on that another day.

Types of swords.

Just some basics, nowhere near exhaustive, of course:

Longswords, from two-handed to hand-and-a-half (or "bastard" sword). Various lengths and styles. Generally used with both hands without a shield. Often, but not always, with armor or chain mail. Note the differences in grip length, overall length, blade cross-section and distal taper:

Oakeshott Type XIIIa

Oakeshott Type XVa

Single-handed swords, generally used with a shield or buckler (small shield, about 12in to 16in in diameter):

Oakeshott Type Xa

Oakeshott Type XVIII

Viking sword. Most commonly had this sort of "lobed" pommel, and a wide fuller running nearly the full length of the blade. Guards where usually short. Sometimes straight, sometimes curved out toward the tip:

Oakeshott Type Z

And just for fun... The Grosse Messer (German for "big knife", for obvious reasons). It's even bigger than it looks. I've handled one, and decided that it was just silly. If you don't get a good hit on the first strike, it's too heavy and slow to recover. You can't help but overcommit. But then again, if you ~do~ get a good hit, you're done with that job:

Well, that's probably enough for now. Some fun stuff, though, huh?

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.