Skip to comments.

House drops Confederate Flag ban for veterans cemeteries

politico.com ^

| 6/23/16

| Matthew Nussbaum

Posted on 06/23/2016 2:04:08 PM PDT by ColdOne

A measure to bar confederate flags from cemeteries run by the Department of Veterans Affairs was removed from legislation passed by the House early Thursday.

The flag ban was added to the VA funding bill in May by a vote of 265-159, with most Republicans voting against the ban. But Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) and Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) both supported the measure. Ryan was commended for allowing a vote on the controversial measure, but has since limited what amendments can be offered on the floor.

(Excerpt) Read more at politico.com ...

TOPICS: Government; News/Current Events; US: Virginia

KEYWORDS: 114th; confederateflag; dixie; dixieflag; nevermind; va

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first previous 1-20 ... 901-920, 921-940, 941-960 ... 1,741-1,755 next last

To: BroJoeK

921

posted on

08/15/2016 11:00:33 AM PDT

by

DiogenesLamp

("of parents owing allegiance to no other sovereignty.")

To: BroJoeK; HangUpNow

Such a war would be yet another example of the utter control of America by rich insiders. No normal American has anything at all to gain by such a war. And no normal American has the slightest influence over whether such a war takes place, except by voting for Trump. The military has become entirely the plaything of unaccountable elites.

...

A point that the tofu ferocities of New York might bear in mind is that wars seldom turn out as expected, usually with godawful results. We do not know what would happen in a war with Russia. Permit me a tedious catalog to make this point. It is very worth making. When Washington pushed the South into the Civil War, it expected a conflict that might be over in twenty-four hours, not four years with as least 650,000 dead.

...

What would Washington do, what would New York make Washington do, having been handed its ass in a very public defeat? Huge egos would be in play, the credibility of the whole American empire. Could little Hillary Dillary Pumpkin Pie force NATO into a general war with Russia, or would the Neocons try to go it alone–with other people’s lives?

http://fredoneverything.org/hillary-trump-and-war-with-russia-the-goddamdest-stupid-idea-i-have-ever-heard-and-i-have-lived-in-washington/

Apparently someone else grasps the concept of how much power the New York elites wield in deciding whether or not Washington D.C. goes to war.

Same stuff, different century.

922

posted on

08/15/2016 1:40:54 PM PDT

by

DiogenesLamp

("of parents owing allegiance to no other sovereignty.")

To: BroJoeK

So that a real reason why Richmond is not the US center of finance, and why Washington, DC is its center of political power. Well, that and the fact that "Roman" New York invaded and destroyed "Carthage" Richmond.

New York is wealthy because they violently suppressed trade by their competitors.

923

posted on

08/15/2016 1:51:54 PM PDT

by

DiogenesLamp

("of parents owing allegiance to no other sovereignty.")

To: DiogenesLamp

DiogenesLamp:

"Well, that and the fact that "Roman" New York invaded and destroyed "Carthage" Richmond." You probably forgot that Richmond, Virginia, was burned down not once, but twice, only the first time by mainly New Yorkers, the second was by Confederates.

But first, some history:

By the year 1800, Richmond, Virginia was the state capital, its population having grown from 200 in 1700 to about 6,000 in 1800.

It was also Virginia's slave trading center, at Shockoe Bottom, where 300,000 slaves were sold into the Deep South from 1800 through 1865.

Richmond's first bank arrived in 1803 followed by roads, bridges, stagecoaches (1812), a 200 mile canal (after 1790), steam boats (1815) & railroads in 1836.

1836 also marked the arrival of Richmond's industrial center, the Tredegar Iron Works.

In 1800, Virginia was the nation's premier state, its status enhanced by the arrival of National Government in the new capital of Washington, DC, just 100 miles north of Richmond.

In short, in 1800 no city in the country was better situated politically than Richmond, Virginia.

So by 1860 Richmond was a prosperous state capital, population growing ten times to roughly 60,000.

Today, Richmond's metropolitan area is home to over a million.

Now let's look at New York City:

By 1800, New York had lost its privileged status as the Nation's Capital, was not even a state capital, but had already grown past Philadelphia's 40,000 population to New York's 60,000 -- despite Philadelphia having recently been the Nation's capital.

And by 1860, commerce, industry & immigration (not politics) drove New York's metropolitan population to well over one million.

Today's New York metropolitan population is around 25 million.

So, while New York City was just 10 times bigger than Richmond in 1800, by 1860 it was 20 times bigger, despite NYC lacking all the political advantages Virginia enjoyed as the home of presidents, generals and the Nation's capital.

Today Metropolitan NYC is nearly 25 times bigger than metro-Richmond.

So, who burned down Richmond, twice?

In 1781 Benedict Arnold lead the American Legion, about 1,200 British loyalists from New York, on a raid to Richmond.

He was met there by just 200 US militia under command of the Governor, Thomas Jefferson, who were quickly defeated and fled the city.

Arnold then demanded a ransom from Jefferson, who refused, so Arnold's loyalist troops burned Richmond, a pattern repeated elsewhere during the Civil War.

Richmond's second burning came in 1865, but this time it was retreating Confederates who set the fires and Union troops who put them out.

924

posted on

08/16/2016 6:13:46 PM PDT

by

BroJoeK

(a little historical perspective...)

To: BroJoeK

And by 1860, commerce, industry & immigration (not politics) drove New York's metropolitan population to well over one million. All a function of it's optimal nature as a Sea Port. Optimal Geographical features are why New York became wealthy. That, and laws designed to favor it, as well as the fact that it's wealth and power gives it leverage to move the government.

But you are missing the point. New York and New England used their influence on the government to stop their Newly acquired Southern competition from intercepting the existing trade with Europe at the expense of New York and New England.

That is why the USA went to war. To serve the interests of the Business Lords of New York.

New York (Rome), Attacked and Destroyed the Competing Cities (Carthage) in the South. They did it to maintain their existing monopoly on trade and manufacturing.

Had they left the South alone, it would have caused massive financial upheaval in New York and New England. Therefore they could not afford to let them do this.

Hence War.

It was a war of subjugation on the Northern side, and a war for Independence on the Southern side.

925

posted on

08/17/2016 6:03:08 AM PDT

by

DiogenesLamp

("of parents owing allegiance to no other sovereignty.")

To: DiogenesLamp

DiogenesLamp: “New York and New England used their influence on the government to stop their Newly acquired Southern competition from intercepting the existing trade with Europe at the expense of New York and New England.

That is why the USA went to war.

To serve the interests of the Business Lords of New York.”

Total & complete rubbish since from the beginnings, Southerners ruled in Washington DC.

Nothing happened they didn’t want or approve of, including the growth of Northern ports.

If you claim that secessionists formed a new Confederacy in order to empower Southern ports, then you are faced with the fact that’s not the reason they gave **at the time**.

Protecting slavery was the reason, the only major reason they gave.

As for why the Confederacy started war at Fort Sumter, the immediate reason was to enforce their sovereignty and humiliate the Union, with the longer-term goal of forcing Upper South states — Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee & Arkansas — to leave the Union & join the Confederacy’s war on the United States.

So, did New York “power elites” somehow force Lincoln to call up 75,000 troops to restore Fort Sumter & other Federal properties?

No, Lincoln merely did what his Oath of Office required, regardless of support, or lack of it from New York.

As it happened, more New Yorkers supported the South, and opposed civil war than in any other Northern city.

So whatever advice Lincoln received from New Yorkers was certainly mixed, pro & con.

That meant Lincoln had to chart his own course, which he did.

Remember, Lincoln was a westerner, an moderate abolitionist and lawyer for railroads.

So his knowledge of or interest in New York financial interests was quite limited.

Even Lincoln’s Secretary of state, Seward, while from New York, came from upstate, not Wall Street, and was a major voice for peace before Fort Sumter.

So all you’re doing is denying historical reality in order to impose nonsensical propaganda where it doesn’t belong.

926

posted on

08/17/2016 8:29:25 AM PDT

by

BroJoeK

(a little historical perspective...)

To: BroJoeK

The men of the Tidewater who crafted it understood that we needed a strong central government for managing trade, national defense and the courts. At the same time, they knew the Puritan lunatics in New England would immediately try to pervert the national government so they could dominate the rest of the country. James Madison had no illusions about the nature of John Adams. The result was a government based on Negative Liberty.

http://thezman.com/wordpress/?p=5885

927

posted on

08/23/2016 3:15:53 PM PDT

by

DiogenesLamp

("of parents owing allegiance to no other sovereignty.")

To: DiogenesLamp

DiogenesLamp:

"James Madison had no illusions about the nature of John Adams." For many years Adams & Jefferson were close friends, unlike Madison, who was Jefferson's protégé.

And neither Adams nor Jefferson attended the Constitutional Convention in 1787, but both were highly influential on it.

Both were responsible for their states' constitutions, constitutions whose patterns & ideas were followed in the new US Constitution.

Yes, some have argued (i.e., Wood 2006) that by 1787, Adams' constitutional ideas were, well, outdated, but that ignores other important contributions Adams made:

"Wood ignored Adams' peculiar definition of the term "republic," and his support for a constitution ratified by the people.[67]

He also underestimated Adams' belief in checks and balances, such as Adams' statement that, 'Power must be opposed to power, and interest to interest.'

This sentiment was later echoed by James Madison's famous statement that, '[a]mbition must be made to counteract ambition', in The Federalist No. 51, explaining the separation of powers established under the new Constitution.[68][69]

Adams was unsurpassed in his dedication to establishing checks and balances as a governing strategem."

Finally Madison, while protégé of Jefferson, was senior to young John Quincy Adams and appointed him to important positions overseas (1809-1817).

Young Adams' good work there led to his subsequent appointment by President Monroe as Secretary of State (1817-1825) prior to Adams' becoming President in 1825.

So those people were often close associates and good friends, regardless of differing political ideas.

928

posted on

08/27/2016 3:57:57 AM PDT

by

BroJoeK

(a little historical perspective...)

To: DiogenesLamp; rustbucket; x; central_va

You referred to the Navigation Act and federal rules governing offshore trade. Since Congress passed the first law, it was changed and revised many times. Permit maybe more detail than you want.

The success of the shipping trade of New England in the early 19th century was a deliberate effort of mercantilism, in which the South at first willingly participated.

Many Southern legislators voted with the majority believing that the revenues would help with the war debt, and struggling American industry. They could not foresee the extent of legislative abuse that would bring the South to economic bondage.

The federal government set out deliberately to encourage and thus favor the commercial trades in the North, especially ship-building and shipping rules. The raw material for Northern factories, and the cargoes of Northern merchantmen, would come from the South.

The July 4, 1789, tariff was the first substantive legislation passed by the new American government. But in addition to the new duties, it reduced by 10 percent or more the tariff paid for goods arriving only in American craft.

It also required domestic construction for American ship registry. Navigation acts in the same decade stipulated that foreign-built and foreign-owned vessels were taxed 50 cents per ton when entering U.S. ports, while U.S.-built and -owned ones paid only six cents per ton. Furthermore, the U.S. ones paid annually, while foreign ones paid upon every entry.

This effectively blocked off U.S. coastal trade to all but vessels built and owned in the United States.

The navigation act of 1817 had made it official, providing “that no goods, wares, or merchandise shall be imported under penalty of forfeiture thereof, from one port in the United States to another port in the United States, in a vessel belonging wholly or in part to a subject of any foreign power.”

The point of all this was to protect and grow the shipping industry of New England, and it worked. By 1795, the combination of foreign competition reduction and American protection put 92 percent of all imports and 86 percent of all exports in American-flag vessels. American ship owners’ annual earnings shot up between 1790 and 1807, from $5.9 million to $42.1 million.

New England shipping took a severe hit during the War of 1812 because of the embargo. After the war ended, the British flooded America with manufactured goods to try to drive out the nascent American industries. They chose the port of New York for their dumping ground, in part because the British had been feeding cargoes to Boston all through the war to encourage anti-war sentiment in New England. New York was the more starved, therefore it became the port of choice. The dumping bankrupted many towns, but it assured New York of its sea-trading supremacy. In the decades to come. New Yorkers made the most of the situation.

Four Northern and Mid-Atlantic ports still had the lion's share of the shipping. But Boston and Baltimore mainly served regional markets. Philadelphia's shipping interest had built up trade with the major seaports on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, especially as Pennsylvania's coal regions opened up in the 1820s. But New York was king. Its merchants had the ready money, it had a superior harbor, it kept freight rates down, and by 1825 some 4,000 coastal trade vessels per year arrived there. In 1828 it was estimated that the clearances from New York to ports on the Delaware Bay alone were 16,508 tons, and to the Chesapeake Bay 51,000 tons.

Early and mid-19th century Atlantic trade was based on “packet lines” — which were groups of vessels under one company banner offering scheduled services. It was a coastal trade at first, but when the Black Ball Line started running between New York and Liverpool in 1817, it became a common way to do business across the Atlantic.

The reason for success was to have a profitable cargo going each way. The New York packet lines succeeded because they took in the majority of European bound cotton cargoes from the South, and Mid-West food exports.

The northeast did not have enough volume of paying freight on its own.

So American vessels, usually owned in the Northeast, sailed off to a cotton port, carrying goods for the southern market. There they loaded cotton, or occasionally naval stores, food, or timber, for Europe. The coastal packets returned to New York where their cargoes were loaded on the large ocean steamers for Europe. They steamed back from Europe loaded with manufactured goods, raw materials like hemp or coal, and occasionally immigrants.

No foreign vessels were excluded from the 1817 law, except a few English ones that could substitute a Canadian port for a Northern U.S. one.

Since Northern business interests were being subsidized by the U.S. government, it was going to continue to be protectionist, and not subject to competition from any nascent Southern shippers.

By creating a three-cornered trade in the ‘cotton triangle,’ New York dragged the commerce between the Southern ports and Europe out of its normal course some two hundred miles to collect heavy handling fees upon it.

This trade might perfectly well have taken the form of direct shuttles between Charleston, Savannah, Mobile, or New Orleans on the one hand and Liverpool or Havre on the other, leaving New York far to one side had the Federal government not interfered in this way.

To clinch this abnormal arrangement, New York developed the coastal packet lines without which it would have been extremely difficult to make the east-bound trips of the ocean packets profitable.

Even when the Southern cotton bound for Europe did not put in at the wharves of Sandy Hook or the East River, unloading and reloading, the combined income from interests, commissions, freight, insurance, and other profits took perhaps 40 cents into New York of every dollar paid for southern cotton. This unnecessarily inflated the cost of cotton for overseas customers and crippled the Southern farmer.

The record shows that ports with moderate quantities of outbound freight could not keep up with the New York competition. Boston started a packet line in 1833 that, to secure outbound cargo, detoured to Charleston for cotton. But about the only other local commodity it could find to move to Europe was Bostonians. Since most passengers en route to England did not want the time delays in a layover in South Carolina, the lines failed.

As for the cotton ports themselves, they did not crave enough imports to justify packet lines until 1851, when New Orleans hosted one sailing to Liverpool.

Yet New York by the mid-1850s could claim sixteen lines to Liverpool, three to London, three to Havre, two to Antwerp, and one each to Glasgow, Rotterdam, and Marseilles. This was subsidized by the federal post office patronage procedure.

U.S. foreign trade rose in value from $134 million in 1830 to $318 million in 1850. It tripled again in the 1850s. Between two-thirds and three-fourths of those imports entered through the port of New York.

This meant that any trading the South did, had to go through New York. Direct trade from Charleston and Savannah during this period was stagnant. The total shipping that entered from foreign countries in 1851 in the port of Charleston was 92,000 tons, in the port of New York, 1,448,000. Relatively little tariff money was collected in the port authority in Charleston.

According to a Treasury report, the net revenue of all the ports of South Carolina during 1859 was a mere $234,237; during 1860 it was $309,222.

New York shipping interests, using the Navigation Laws and in collaboration with the US Congress, effectively closed the market off from competitive shipping, and in spite of the inefficiencies, were able to control the movement of Southern goods.

In an effort to enable Charleston to enter the international trade, the citizens of the state financed a dredging project in the late 1850’s that produced a ship channel that would now accommodate the deep draft cargo ships directly from Europe. It was finished in 1860.

This combined with the power of the Mississippi caused a number of Governors to meet with Lincoln as he assumed power.

(Credit rustbucket, nolochan, GopCapitalist, and several books and US Treasury data for this.

To: PeaRidge

To: PeaRidge

Thanks for that economic/trade information. It dovetails nicely with the circumstances as I understand them.

The power brokers of New York/New England could not afford to let the South become independent. It would cost them too much money.

So far as I can find, the total GDP in 1860 was about 4.5 billion dollars. Do you have any sources that can break this down by region?

I want to find out what component of the total was created by European trade and what was created by States not involved in European trade. (Such as California gold mining and Nevada Silver mining.) We can get a clearer picture of how important it was to keep the South for economic reasons if we separate out the parts of the GDP that had nothing to do with trade with Europe.

300 million doesn't seem like much when compared to 4.5 billion, but it may have been massively significance in the finances of the New England/New York area. We just need to cut out from the total the finances produced by other areas of the country such as California, Oregon, etc.

931

posted on

08/29/2016 6:39:59 AM PDT

by

DiogenesLamp

("of parents owing allegiance to no other sovereignty.")

To: PeaRidge; rustbucket; DiogenesLamp; x; rockrr

Thanks for your very informative summary.

It is, however, misleading in several respects, of which I'll mention a few.

PeaRidge: "Many Southern legislators voted with the majority believing that the revenues would help with the war debt, and struggling American industry.

They could not foresee the extent of legislative abuse that would bring the South to economic bondage."

But there was no "bondage" -- none, zero, nada -- because all such economic relationships were voluntary, including the protectionist tariff laws.

That's because they were first proposed and agreed to by Southerners (i.e., Washington, Jefferson, Madison, etc.) and over many decades rose and fell under Southern influences.

Even the highest, the so-called Tariff of Abominations, was originally favored by Southern President Jackson and Vice President Calhoun.

And when other Southerners chaffed under those high rates, they were soon drastically reduced.

Further, there was nothing -- nothing! -- in those laws which prevented wealthy Southerners (of whom there were many) from building their own ships and transporting their own exports to Europe.

Indeed, this site says that's exactly what happened in New Orleans which, it says, shipped one half the Southern cotton crop in the 1850s.

PeaRidge: "The raw material for Northern factories, and the cargoes of Northern merchantmen, would come from the South."

But there were no factories in the North -- none, nada, zero -- which could not lawfully have been built in the South, much closer to their raw materials, had Southerners been truly interested in doing so.

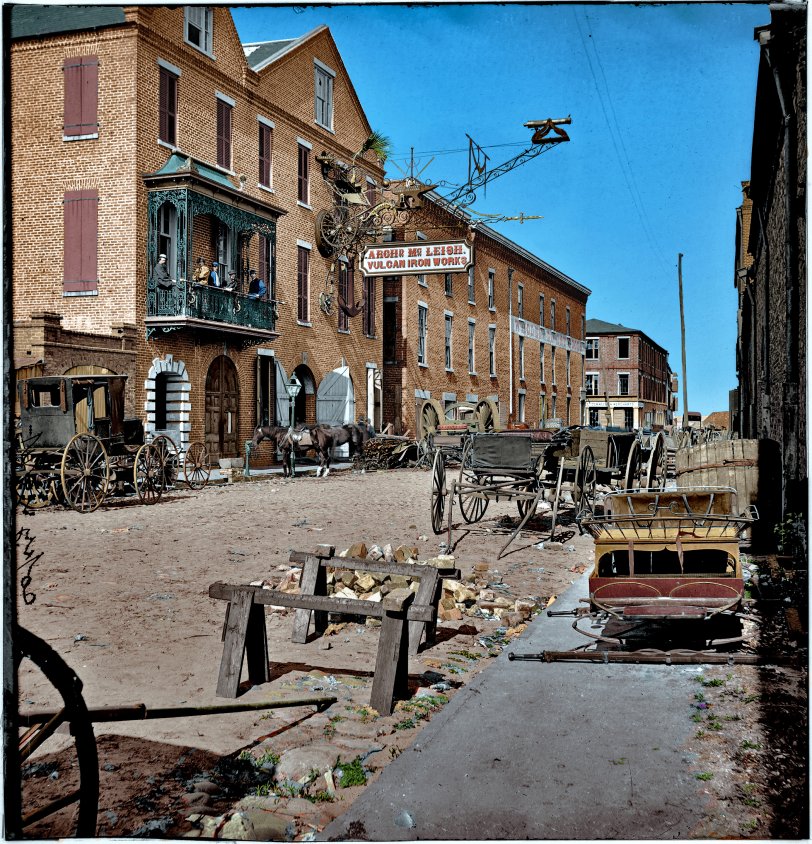

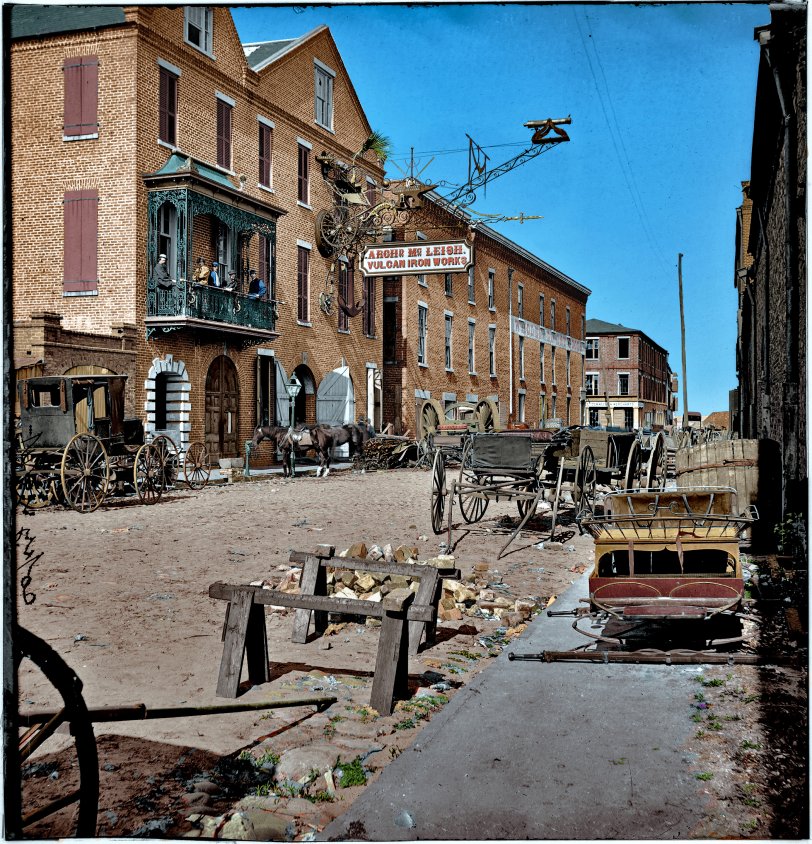

Indeed, by 1850 there were a number of Southern factories including Tredegar Iron Works near Richmond, Clarksville Iron Works in Tennessee, Vulcan Iron Works in Charleston, South Carolina and Tannehill Iron Works in McCalla, Alabama.

So the facts prove that nothing stopped Southerners with a true love of factory manufacturing.

PeaRidge: "The point of all this was to protect and grow the shipping industry of New England, and it worked.

By 1795, the combination of foreign competition reduction and American protection put 92 percent of all imports and 86 percent of all exports in American-flag vessels."

Again, nothing prevented Southerners from building & operating their own ships -- as the Civil War demonstrated, when ports all around the Confederacy began constructing ships for the Confederate Navy and blockade running.

PeaRidge: "The New York packet lines succeeded because they took in the majority of European bound cotton cargoes from the South, and Mid-West food exports."

Again, half the Southern cotton crop shipped from New Orleans, not New York.

Of those New Orleans shipments, only 15% went to Northern US manufacturers, the rest was exported globally.

PeaRidge: "So American vessels, usually owned in the Northeast, sailed off to a cotton port, carrying goods for the southern market.

There they loaded cotton, or occasionally naval stores, food, or timber, for Europe."

But no law prevented those ships from being built, owned and operated by Southerners, as indeed we can well suppose that those operating out of New Orleans were.

Now I'm out of time again, must run.

Will come back to this later...

Vulcan Iron Works, Charleston, SC, 1865:

932

posted on

08/30/2016 5:53:04 AM PDT

by

BroJoeK

(a little historical perspective...)

To: DiogenesLamp

To: PeaRidge; DiogenesLamp; rustbucket; x; rockrr

PeaRidge:

"Since Northern business interests were being subsidized by the U.S. government, it was going to continue to be protectionist, and not subject to competition from any nascent Southern shippers." Complete rubbish, since those protectionist tariffs protected any US manufacturer & shipper, North, South, East or West.

No law stopped Southerners from building, owning & operating their own ships, as for certain they did in large Southern cities like New Orleans and Baltimore.

And no US Federal law favored Northern owned over Southern owned ships, factories or products.

The only real issue was: where did wealthy men in each region think they could achieve the highest returns for their investment money?

The answer in the South was clearly and consistently: by investing in slaves to produce cotton, tobacco, sugar and other such cash crops.

So the real reason there were fewer Southern factories and ships was because Southerners believed slaves were a much better investment.

And in that, they were arguably correct, since by 1860 the average white slave-owning Deep South citizen was significantly better off than his Northern cousins.

PeaRidge: "By creating a three-cornered trade in the ‘cotton triangle,’ New York dragged the commerce between the Southern ports and Europe out of its normal course some two hundred miles to collect heavy handling fees upon it."

But nothing prevented Southerners from building, owning and operating their own ships, so collecting their own heavy handling fees, as for certain they did in such ports as New Orleans.

PeaRidge: "This trade might perfectly well have taken the form of direct shuttles between Charleston, Savannah, Mobile, or New Orleans on the one hand and Liverpool or Havre on the other, leaving New York far to one side had the Federal government not interfered in this way."

But we already know that cotton and other mid-West products certainly did ship directly from New Orleans to global customers.

In the 1850s, New Orleans shipped half of all US cotton, and only 15% of that went to Northern US manufacturers.

So the Federal Government interfered with nothing

PeaRidge: "New York developed the coastal packet lines without which it would have been extremely difficult to make the east-bound trips of the ocean packets profitable."

And New Orleans had hundreds of river boats steaming up and down the Mississippi, with all its tributaries, collecting US product to ship globally.

We know the pilot for many of those steamboats, a young Southerner, later Confederate soldier, named Samuel Clements.

So, do we claim that all those Northern Mid-west producers were in "economic bondage" to Southerners like young Sam Clements?

No, that's absurd, it was business and people did what seemed in their overall best interests.

PeaRidge: "...combined income from interests, commissions, freight, insurance, and other profits took perhaps 40 cents into New York of every dollar paid for southern cotton.

This unnecessarily inflated the cost of cotton for overseas customers and crippled the Southern farmer."

That is so patently absurd, you can't be posting with a straight face!

In fact, the decade of the 1850 was the most prosperous period in the history of mankind for average slave-holders in the Deep South.

And along with them, all the shop-keepers and skilled workers they employed.

On average they were significantly better off than their average Northern cousins.

So nobody was "crippled", but each invested their savings in such businesses as they believed would return the greatest profits.

For Southerners that was slavery.

PeaRidge: "The record shows that ports with moderate quantities of outbound freight could not keep up with the New York competition."

No, the record shows that in terms of cotton exports, New Orleans shipped as much as all other US ports combined!

PeaRidge: "As for the cotton ports themselves, they did not crave enough imports to justify packet lines until 1851, when New Orleans hosted one sailing to Liverpool."

Your data is totally flawed, since this site gives a much clearer picture of the importance of New Orleans throughout the antebellum period.

In fact, New Orleans cotton exports alone equaled all other US ports combined.

In addition, New Orleans exported product from all over the Northern mid-west, serving the same purpose for them that New York performed on the East coast.

Among those antebellum Northerners who took their produce to New Orleans for sale was a young Illinoisan named Abraham Lincoln -- twice, in 1828 and 1831.

So New Orleans was a big deal to millions who lived west of the Appalachians.

PeaRidge: "Between two-thirds and three-fourths of those imports entered through the port of New York.

This meant that any trading the South did, had to go through New York."

Because between 2/3 and 3/4 of all Americans lived in the North!

But your suggestion that all those ships from New Orleans to global markets returned home empty is a bit far-fetched.

My guess is they were just as eager to find return cargoes as any Northeasterner.

PeaRidge: "According to a Treasury report, the net revenue of all the ports of South Carolina during 1859 was a mere $234,237; during 1860 it was $309,222."

That's because South Carolina was one of the smallest and least populous of all Confederate states.

Only Florida in 1860 had fewer whites than South Carolina.

So there is no reason to suppose that South Carolina would have any trade advantages over other more populated and more prosperous Southern states.

PeaRidge: "New York shipping interests, using the Navigation Laws and in collaboration with the US Congress, effectively closed the market off from competitive shipping, and in spite of the inefficiencies, were able to control the movement of Southern goods."

Total rubbish, since only foreign owned ships were highly taxed.

Any US owned ships -- Northern, Western or Southern -- were free to compete for business anywhere in the country.

This is clearly seen when you consider the role of New Orleans.

PeaRidge: "This combined with the power of the Mississippi caused a number of Governors to meet with Lincoln as he assumed power."

Doubtless Lincoln met with hundreds of important people in the months before and after taking his Oath of Office on March 4, 1861.

934

posted on

08/31/2016 5:51:08 AM PDT

by

BroJoeK

(a little historical perspective...)

To: PeaRidge; DiogenesLamp; rustbucket; x; rockrr

BJK:

"No law stopped Southerners from building, owning & operating their own ships, as for certain they did in large Southern cities like New Orleans and Baltimore." I made much of New Orleans, but didn't mention Baltimore in any detail.

This source and this source show that as of 1840 Baltimore and New Orleans had the same population, 102,000 souls.

However, according to this source, by 1860 Baltimore outnumbered New Orleans by 25% -- Baltimore's 212,000 to New Orleans 169,000 population.

And for many decades Baltimore was a major competitor with New York for coastal packets delivering cotton for shipment to Liverpool.

But Baltimore was also highly diversified into tobacco, flour, grains, clothing, tanning, tin & sheet iron ware products, foundry & machine shop products and railroad cars.

Baltimore was the first Eastern city to extend railroads to the Ohio River -- B&O Railroad.

Yes, Baltimore was not the King Cotton & Midwest produce shipping center like New Orleans, but by 1860 it was still the larger and more economically diversified city, third only behind New York and Philadelphia.

So Baltimore and New Orleans both demonstrated that Southerners were fully capable of competing both nationally and globally, in processing, manufacturing and shipping.

But in 1860, those cities served a white population of around 8 million, while New York, Philadelphia and Boston served nearly three times more, and so were, not surprisingly, correspondingly larger.

Antebellum New Orleans:

Antebellum Baltimore:

USS Constellation built in Baltimore, 1797:

935

posted on

08/31/2016 12:00:24 PM PDT

by

BroJoeK

(a little historical perspective...)

To: rustbucket; PeaRidge

936

posted on

09/01/2016 11:33:42 PM PDT

by

StoneWall Brigade

( America's Party! Tom Hoefling/Steve Schulin 2016)

To: DiogenesLamp

To: PeaRidge

To Hell it wasn’t about slavery. Tell me something professor, if the South had won the war would it have freed the slaves?

938

posted on

09/12/2016 4:58:04 PM PDT

by

jmacusa

("Dats all I can stands 'cuz I can't stands no more!''-- Popeye The Sailorman.)

To: jmacusa

Being dhimmicrats, when the slavers discovered how unpopular slavery had become in the civilized world, they probably would have just given the term a euphemistic overhaul - you know - something like “pea-pickers”.

939

posted on

09/12/2016 6:11:48 PM PDT

by

rockrr

(Everything is different now...)

To: jmacusa

You don’t need me for that. You already know the answer.

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first previous 1-20 ... 901-920, 921-940, 941-960 ... 1,741-1,755 next last

Disclaimer:

Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual

posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its

management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the

exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.

FreeRepublic.com is powered by software copyright 2000-2008 John Robinson