Posted on 04/04/2006 6:13:56 PM PDT by Tailgunner Joe

A common and false impression about America’s Founding Fathers is that they were deists -- that is, they believed in a "watchmaker" God who set the universe in motion and then stepped aside to let it run itself. The deist god lacks the interest, or the power, to intervene in human affairs.

Michael Novak, a celebrated theologian and author, convincingly rebutted this misconception in his book, "On Two Wings: Humble Faith and Common Sense at the American Founding." In "Washington's God," Novak and his daughter Jana turn their attention to the religious beliefs of America's first and greatest President. The Novaks' book, undertaken at the request of the resident director of the Mount Vernon Estate, is unquestionably the most thorough and systematic examination of Washington's religious views written to date.

Deism Myth

Most biographies of Washington have devoted little time or study to Washington's religious beliefs, accepting without question the prevailing view that Washington was a deist. But the god of the deists, as the Novaks note, is an impersonal god who does not intervene in history. This is manifestly not the God in whom Washington believed. On the contrary, Washington's private correspondence and public statements are replete with his pleas to seek God's help and protection and his assertions that God has provided such assistance.

Washington's thought was infused with God, a fact made plain by the fact that he used more than 80 terms to refer to the Deity, among them "Almighty God," "Creator," "Divine Goodness," "Father of all mercies," "Jehovah," "Lord of Hosts," "Maker" and "God of Armies."

The most common term he employed was "Providence," which some historians have interpreted as indicating an impersonal deity. The Novaks provide extensive contextual information on the times, however, demonstrating that the philosophical language of the enlightenment was widely used by people with orthodox religious beliefs.

They provide example after example to prove conclusively that the "Divine Providence" whom George Washington invoked was an active agent in human events. Here, for instance, is one of Gen. Washington’s orders to his troops during the Revolution:

"The General commands all officers, and soldiers, to pay strict obedience to the orders of the Continental Congress and by their unfeigned and pious observances of their religious duties, incline the Lord and Giver of victory to prosper our arms."

Or this, from Washington’s Second Thanksgiving Proclamation of 1795:

"... The happy course of our public affairs in general, the unexampled prosperity of all classes of our citizens, are circumstances which peculiarly mark our situations with indications of the Divine beneficence toward us; In such state of things it is an especial manner of duty as a people with devout reverence and affectionate gratitude, to acknowledge our many and great obligations to Almighty God and to implore him to continue and confirm the blessings we experience."

As the authors point out, one does not approach the impersonal god of deism with requests for favor and protection because no such requests would be heard or answered.

An Active God

Washington’s God, on the other hand, is active in history, working through mankind to achieve his purposes -- some of which, Washington knew, are beyond our ken at the present time. One purpose he quite clearly discerned, however, was "the lot that providence has assigned us ... as the actors on a most conspicuous theater, which seems peculiarly designed by providence for the display of human greatness and felicity."

As the authors note, Washington saw the American Revolution as more than a mere struggle for independence. He saw that "there was a chance here to create a new experiment in liberty for the benefit of the entire human race."

In sum, the Novaks make an overwhelmingly persuasive case that Washington was not a deist -- that his god was the God of the Bible, Jehovah. This was a god who continued to intervene in history on behalf of the fledgling American nation, in a sense the new "chosen people," as he did for the chosen people of old -- the Israelites.

As to the question of whether Washington was a Christian, the answer is less clear. Yet here, too, the evidence the authors adduce is persuasive that he was.

They note that Washington was born into the Anglican faith (as were many of the founders). Unlike Thomas Jefferson, he never rejected that faith but, instead, was a life-long churchgoer -- frequently making the seven-mile trip to worship at Pohick Church or, less frequently, the nine-mile trip to Christ Church in Alexandria.

Moreover, Washington served for more than 15 years as a warden and vestryman in the church, a position that requires a substantial amount of time, labor and money, and assent to the doctrine of the Anglican faith.

The Anglican services were centered on the Book of Common Prayer which required the regular recitation by the congregation of the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds, which Washington -- never accused even by his enemies of hypocrisy -- did regularly and willingly his whole life.

Washington also agreed to be a godparent for at least eight children, a far from casual commitment in that it required the godparents to agree to help insure that the child was raised in the Christian faith. Thomas Jefferson declined the honor of godfather on numerous occasions precisely because he thought he could not in good conscience agree to this Christian responsibility. Washington had no such qualms and indeed presented his godsons and goddaughters with Bibles and prayer books.

Practicing Anglican

Again, Washington lived his whole life as a practicing Anglican (as a member of the Church of England before the Revolution and as an Episcopalian after independence).

Washington was reluctant to discuss his personal Christian faith publicly, but as the authors show, there are cases in which he did.

In a general order to the troops dated May 2, 1778, for instance, he wrote:

"To the distinguished character of patriot, it should be our highest glory to add the more distinguished character of Christian."

A year later in a speech to the Delaware chiefs he said, "You do well to wish to learn out arts and ways of life and above all the religion of Jesus Christ."

In a letter to Benedict Arnold dated Sept. 14, 1775, he wrote, "Prudence, policy and a true Christian spirit will lead us to look with compassion upon their errors [those of the Canadians] without insulting them."

Similarly, in a letter written to Gen. George Putnam on Oct. 19, 1777, Washington expresses sympathy for the loss of the general's wife:

"Remembring [sic] that all must die and that she had lived to an honorable age, I hope you will bear the misfortune with that fortitude and complacency of mind that becomes a man and a Christian."

And finally, in a circular to the states written on June 8, 1783, at the end of the war, a document that has become famous as "Washington's Prayer," the General prayed:

"I now make it my earnest prayer, that God would have you, and the state over which you preside, in his holy protection, that he would incline the hearts of the citizens to cultivate a spirit of subordination and obedience to government, to entertain a brotherly affection and love for one another, for their fellow citizens of the United States at large, and particularly for their brethren who have served in the field, and finally, that he would most graciously be pleased to dispose us all, to do justice, to love mercy, and to demean ourselves with that charity, humility and pacific temper of mind, which were the characteristics of the Divine Author of our blessed Religion, and without an humble imitation of whose example in these things, we can never hope to be a happy nation."

Other reasons to support the conclusion that Washington was a Christian include:

The Novaks argue that Washington sought assiduously a religious vocabulary that would seem inclusive to all of the many Christian denominations and sects as well as to Jews -- all of whom he esteemed as equal citizens of the new nation -- a conclusion buttressed by the many letters he wrote to those groups.

To those who knew him best, however, there were few doubts about Washington's own religious beliefs. Many testified that he was, both in his beliefs and the way he lived his life, the very model of a Christian gentleman.

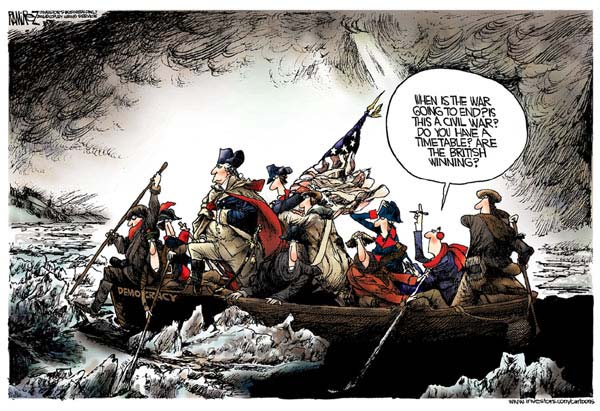

Nice picture.

More than a 1000 words.

Which is very appropriate, but liberals use this to redefine all the founder's personal beliefs. Some were deists. But even that is beside the point. All were equal citizens regardless of their specific religious beliefs.

A telling fact is that on his deathbed, from a lingering illness, he summoned no priest nor clergy.

Where the rubber would meet the road is whether or not Washington indulged in private prayer. I don't deists of any stripe would do that, and private prayer is not just upholding the culture as a public man, or man of affairs.

You might want to give the book a look. Michael and Jana Novak thoroughly address your very deathbed question. Washington, as were many of his contemporaries, was a very "low-church" Anglican, one who would not see a necessity for Last Rites, yet who was liturgical enough in his sensibilities to practice his faith in a way that was quiet rather than heart-on-his-sleeve. His final words were "'Tis well," the period's Anglican "amen," uttered as his wife prayed over him.

"Christian Gentleman," perhaps.

"Born Again" through repentance and acceptance of God's only provision for sin, Who is Jesus Christ... doubtful.

Very doubtful.

Spiritually, George Washington is far more known as a Freemason than as any kind of real Born Again Believer. Google "washington freemason," and you'll see this clearly.

All masonic objections notwithstanding, Jesus Christ and Freemasonry are utterly incompatible.

Jesus Christ: "Ye must be born again."

Freemasonry: "We reverance all the great reformers. We see Moses, Confucius, Zoroaster,...Jesus of Nazareth...as great teachers of morality, if no more. Allowing every brother of the order to freely assign to these...even divine character, if his creed and truth require." Albert Pike, Morals and Dogma.

Believe what you like, but do so according to knowledge. A man who is a disciple of Jesus Christ should walk even as He walked. (As saith the LORD. 1 John 2:6)

Uprightness, morality, and a respect for church, God, the Bible, and Christianity are not the same thing as being "Born of water and the Spirit." Millions accept the former while rejecting the latter, and are in the process of creating their own righteousness via works. This is anathema to true Christianity.

Philippians 3:9, "And be found in him, not having mine own righteousness, which is of the law, but that which is through the faith of Christ, the righteousness which is of God by faith."

Romans 10:6-12, "But the righteousness which is of faith speaketh on this wise,...

"That if thou shalt confess with thy mouth the Lord Jesus, and shalt believe in thine heart that God hath raised him from the dead, thou shalt be saved.

"For with the heart man believeth unto righteousness; and with the mouth confession is made unto salvation.

"For the scripture saith, Whosoever believeth on him shall not be ashamed."

Upon his death he was put into a temporary crypt while his tomb was built to his exact specifications.

As it turned out the tomb is quite simple. It has his name. But unlike Jefferson no eulogy or reference to accomplishments.

Instead, there is one verse from the Bible which still asks a question. The verse is John XI:XXVI. The verse prior says "Jesus said to her, I am the resurrection and the life. Whoever believes in me, though he die yet he shall live."

And here is the specific verse and question for whoever would look up the reference carved into Washington's tomb: "And everyone who lives and believes in me shall never die. Do you believe this?"

I might add that Freemasonry was in it's infancy in the late 1700's and did not have the current belief system that developed in the wake of early 1800's unitarianism.

Thank you, Z.Hobbs. Your post numbers 10 and 11 say far more historically and correctly speaking than OneRoomSchooling's post #9.

I can quote scripture as well as anyone else and I often do, as I have taught courses in Biblical apologetics. Speaking as one who long ago stood where OneRoom does now; however, I found that a little more knowledge and a lot less uninformed judgment of our Founding Fathers goes a long way in one's pursuit of historical accuracy.

"on his deathbed, from a lingering illness, he summoned no priest nor clergy."

All that means is that he wasn't Catholic, but we already knew that.

"I might add that Freemasonry was in it's infancy in the late 1700's"

But the Masonic cult was in its infancy in ancient Babylon (or earlier).

In 1798, a Reformed minister, the Rev. G.W. Snyder, wrote to Washington with a question much like yours. Washington responded in a September 25, 1798 letter that he wished to "correct an error you have run into, of my Presiding over the English lodges in this Country. The fact is, I preside over none, *nor have I been in one more than once or twice, within the last thirty years*."

It is important to note, as several others have posted, that 18th-Century Freemasonry did not carry the "religious," non-Christian implications it does today. Many early masons were Calvinists and Anglicans of various stripes who loosely associated with lodges to do charity work. One of Washington's few visits to a Masonic lodge involved the lodge's use as a gathering place prior to a walk over to the local church.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.