|

are acknowledged, affirmed and commemorated.

|

Posted on 07/17/2003 12:00:55 AM PDT by SAMWolf

|

are acknowledged, affirmed and commemorated.

|

| Our Mission: The FReeper Foxhole is dedicated to Veterans of our Nation's military forces and to others who are affected in their relationships with Veterans. In the FReeper Foxhole, Veterans or their family members should feel free to address their specific circumstances or whatever issues concern them in an atmosphere of peace, understanding, brotherhood and support. The FReeper Foxhole hopes to share with it's readers an open forum where we can learn about and discuss military history, military news and other topics of concern or interest to our readers be they Veteran's, Current Duty or anyone interested in what we have to offer. If the Foxhole makes someone appreciate, even a little, what others have sacrificed for us, then it has accomplished one of it's missions. We hope the Foxhole in some small way helps us to remember and honor those who came before us.

|

|

The small passage between Argentan and Falaise, where German armies tried desperately to escape, was one of the great slaughters of World War II. The ground was so littered with fallen equipment and corpses that, after the shooting had ceased, passage through the area was almost impossible. “Here the once-vaunted German Fifth Panzer and Seventh armies bled to death”. Supreme Commander Dwight Eisenhower, when traveling by foot through the area, quoted, “it was literally possible to walk for hundred of yards at a time, stepping on nothing but dead and decaying flesh”. But the allied victory was tainted with uncertainty; how many Germans escaped the trap of the Falaise Pocket because of a delayed closing of the encirclement? .jpg) The German troops were in chaos, and had no real chance to defend against an oncoming onslaught. As George Patton drove toward Argentan, and the British and Canadian forces captured Caen, he was ordered by General Omar Bradley stop his drive for fear that Patton might charge into Bernard Montgomery’s men. Patton protested vehemently, because he felt that by advancing further, he could capture Falaise and consequently have every German in Normandy in his grasp. Because the war seemed to be almost over, Eisenhower, who backed Bradley’s order, and Bradley himself cared little that the Germans escaped. The attack on the night of August 7 toward Falaise was a key Canadian operation. At 11:00 p.m., 1,020 heavy bombers dropped 3,500 tons of bombs on the flanks of the ground assault, and a total of 720 artillery barrels bombarded the enemy and lighted the battlefield. At dawn on August 8th, the Canadian troops had broken the German defense and the road to Falaise was wide open. The Canadian forces came to a halt though, and did not start again until 12:30 p.m..  Tanks of the 21st panzer Division in ambush The Canadians, along with the Poles, had trouble getting started and allowed the Germans to reorganize their defenses. The offensive sputtered and eventually dissipated, but the Germans were still being attacked by the Americans and British on two other sides. Depression was rampant in the German high command, and General Bradley could not contain his elation on the morning of August 8th. While the Canadians slowly fought on toward Falaise, the Americans battled the Germans at Mortain. Patton and Bradley disagreed in their assessment of the situation: Patton wanted to outrun the Germans and consequently fully encircle them; Bradley was concerned about what was happening at Mortain, and suggested a hook to threaten the Germans there. Bradley argued that his drive would complement the Canadians’ drive on Falaise and their meeting would trap an estimated twenty-one German divisions. He was concerned about safety while Patton wanted to rid Normandy of all Germans so the Allies could advance on Germany with ease. Both plans were based on the idea of encircling the Germans in one “pocket.” Hitler, with growing concern over Normandy, wanted six panzer divisions to advance on Avranches while two additional supported them; he later issued an order to increase the attack on Avranches. Hans van Kluge felt that Hitler’s instructions could not be carried out because the Germans had to continually hold of the Canadians at Falaise while also preventing the Americans from obtaining Alençon, and encircling them. However, Alençon interested Bradley less than Mortain because he continued to see the Germans in that region as a threat.  US. troops advance On August 11, Montgomery issued a new plan of how to encircle the Germans. He figured that if the Canadians reached Falaise and the Americans entered Alençon, thirty-five miles would separate them, and the Allies would take control of two of the three main east-west highways, surrounding the Germans. It was vital for the Canadians to obtain Falaise quickly and for Miles Dempsy’s British Army to push eastward to both Falaise and Argentan. The Americans, under Patton, advanced very quickly on Alençon while the Canadian army continued slowly toward Falaise. This was because the Canadians were meeting much stronger resistance from the Germans than the Americans were. The Germans, sensing the Allied advance, retreated from Mortain during the night of August 11th and took over the town of Argentan on August 12th.  Despite the Germans’ quick capturing of Argentan, Wade Haislip’s forces took over Argentan and were ready to advance toward Falaise to meet the Canadians and therefore entrap the Germans. To Patton and Haislip’s surprise, Bradley said that in order to prevent a collision between the Canadians and the Americans, they should stay in Argentan and not advance on Falaise. It was one of the most controversial decisions of the campaign. Dempsey was now attacking Falaise along with the Canadians, and when it fell, Montgomery would have the Canadians meet the Americans to close the pocket. On August 16th, the Canadians finally arrived in Falaise and Hitler allowed Kluge, who later committed suicide, to retreat from the pocket. Crerar, the Canadian commander, after obtaining control of this long sought after Falaise, was ordered to head for Trun and Chambois, and push south until he met the Americans who were coming north. At the same time, the British were ordered to approach Chambois from the west. The Germans in the west part of the pocket retreated toward the Orne River that night, and were not interfered with by the Allies. The Canadians and Poles found their way to Trun heavily blocked by the Germans, but by evening were only two miles short of the town. The Germans, realizing that hope was lost, resumed their withdrawal to the Orne River under heavy Allied artillery fire. Eisenhower assumed command of the Allied ground forces on September 1st, and the Allies finally closed the gap. However, the pocket was like a sieve, and many Germans poured through the under-defended barrier.  Abandoned German equipment litters a road (DA photograph) Despite many setbacks on the Allied side, the Falaise pocket was one of the bloodiest campaigns in the War. The fleeing Germans were attacked on all sides by the Canadians, Americans, British, and Poles, and could not sustain a steady defense much less and offense. Over 10,000 Germans were killed, 60,000 were injured, and 50,000 were taken prisoner; they also had more than 1,000 guns, tanks, and trucks destroyed . One can only imagine how badly the Germans would have been defeated if Patton had had his way. Raymond Callahan said, “In the end, the Falaise pocket gave the Allies a great, if an incomplete victory”.

|

The Battle of Mortain must be counted among the most important battles in the west and recognized for what it was-a true example of air-land action. It set the stage for the next and even greater disaster to befall German arms in France-the battle of the Falaise-Argentan pocket. After Mortain, the only course open to the Wehrmacht was headlong retreat toward the German frontier. In that retreat. Allied tactical air would offer no respite.

In retrospect, air was more critical-and under greater pressure-at Mortain than at the subsequent fighting in the Falaise-Argentan pocket. Mortain was an Allied defensive battle whereas Falaise was an encirclement and an attempt to prevent the Germans from escaping out of the trap eastward. As the perimeter closed down, the pocket became a gap, and the Allies struggled to close it. The Falaise campaign probably began on August 7, the same day as the German counterattack at Mortain, when Canadian troops launched a ground assault called Totalize toward Falaise. For the next two weeks. Allied troops-British, American, and Polish- harassed the German forces caught inside the pocket until finally, on August 21, the gap was closed.

Eventually, the Canadians pressed south from Falaise, the Americans north from Argentan, and both sought to narrow and close the gap by reaching the road network across and beyond the Dives River, at Trun, St. Lambert, Moissy, and Chambois. The roads beyond led toward Vimoutiers, tunneling German forces into predictable killing grounds. Polish forces fought an especially prolonged and bitter struggle at Chambois that echoed Mortain's lone battalion. On August 19, the Poles seized Chambois (soon dubbed "Shambles"), establishing defensive positions on Mont Ormel, to the northeast. Here was an ideal vantage point to call in artillery and air strikes on the German forces streaming across the Dives and past their positions.

Extremely bitter fighting broke out between Polish and retreating German forces, but the Poles were able to retain control until the gap closed on August 21. The countryside around the Dives and Orne rivers was generally open, with sporadic patches of forested areas. The high ground across the Dives-specifically Mont Ormel-furnished an unparalleled vista of the entire gap area. In the third week of August 1944, this vista was marred by the near-constant bursting of bombs, rockets, and artillery, the ever-present drone of fighter-bombers and small artillery spotters (the latter especially feared and loathed by German forces), the corpses of thousands of German personnel and draft animals, and the burning and shattered remains of hundreds of vehicles and tanks. It was a scene of carnage without parallel on the Western Front.

Because the Luftwaffe was absent over the battlefield. Broad-hurst directed 2 TAF wings to operate their aircraft in pairs. Thus, a "two ship" of Spitfires or Typhoons could return to the gap after being refueled and rearmed without waiting for a larger formation to be ready to return. This maximized the number of support sorties that could be flown, and, indeed, pilots of one Canadian Spitfire wing averaged six sorties per day. Nothing that moved was immune from what one Typhoon pilot recollected as "the biggest shoot-up ever experienced by a rocket Typhoon pilot." Another recalled the flavor of attack operations:

The show starts like a well-planned ballet: the Typhoons go into echelon while turning, then dive on their prey at full throttle. Rockets whistle, guns bark, engines roar and pilots sweat without noticing it as our missiles smash the Tigers. Petrol tanks explode amid torrents of black smoke. A Typhoon skids away to avoid machine fire. Some horses frightened by the noise gallop wildly in a nearby field.

That morning 37 P-47 pilots of the 36th Group found 800 to 1,000 enemy vehicles of all types milling about in the pocket west of Argentan. They could see American and British forces racing to choke off the gap. They went to work. Within an hour the Thunderbolts had blown up or burned out between 400 and 500 enemy vehicles. The fighter-bombers kept at it until they ran out of bombs and ammunition. One pilot, with empty gun chambers and bomb shackles, dropped his belly tank on 12 trucks and left them all in flames.

Four days later another Thunderbolt squadron, below-strength, flew over a huge traffic jam, radioed for assistance, 'and soon the sky was so full of British and American fighter-bombers that they had to form up in queues to make their bomb runs.' The next day, 36th Group Thunderbolts spotted another large German formation, marked out by yellow artillery smoke. Since the vehicles were in a zone designated as a British responsibility, XIX TAC sat back 'disconsolately' while 2 TAF launched a series of strikes that claimed almost 3,000 vehicles damaged or destroyed. On August 19, one Spitfire wing put in a claim for 500 vehicles destroyed or damaged in a single day; that same day, another Spitfire wing claimed 700.

www.ehistory.com

search.eb.com

www.brooksart.com

www.army.mil

www.valourandhorror.com

www.saintjohn.nbcc.nb.ca

www.military-art.com

www.stenbergaa.com

ON THE WESTERN FRONT, August 21, 1944--When you're wandering around our very far-flung front lines--the lines that in our present rapid war are known as "fluid"--you can always tell how recently the battle has swept on ahead of you. You can sense it from the little things even more than the big things-- From the scattered green leaves and the fresh branches of trees still lying in the middle of the road. From the wisps and coils of telephone wire, hanging brokenly from high poles and entwining across the roads. From the gray, burned-powder rims of the shell craters in the gravel roads, their edges not yet smoothed by the pounding of military traffic. From the little pools of blood on the roadside, blood that has only begun to congeal and turn black, and the punctured steel helmets lying nearby. From the square blocks of building stone still scattered in the village street, and from the sharp-edged rocks in the roads, still uncrushed by traffic. From the burned-out tanks and broken carts still unremoved from the road. From the cows in the fields, lying grotesquely with their feet to the sky, so newly dead they have not begun to bloat or smell. From the scattered heaps of personal debris around a gun. (I don't know why it is, but the Germans always seem to take off their coats before they flee or die.) From all these things you can tell that the battle has been recent--from these and from the men dead so recently that they seem to be merely asleep. And also from the inhuman quiet. Usually battles are noisy for miles around. But in this recent fast warfare a battle sometimes leaves a complete vacuum behind it. The Germans will stand and fight it out until they see there is no hope. Then some give up, and the rest pull and run for miles. Shooting stops. Our fighters move on after the enemy, and those who do not fight, but move in the wake of the battles, will not catch up for hours. There is nothing left behind but the remains--the lifeless debris, the sunshine and the flowers, and utter silence. An amateur who wanders in this vacuum at the rear of a battle has a terrible sense of loneliness. Everything is dead--the men, the machines, the animals--and you alone are left alive. -- Ernie Pyle |

Today's classic warship, USS Talladega (APA-208)

Haskell class attack transport

Displacement. 12,460

Lenght. 455'

Beam. 62'

Draft. 24'

Speed. 17.7 k.

Complement. 692

Troop Capacity. 1,562

Armament. 1 5", 12 40mm

USS Talladega (APA-208) was laid down under Maritime Commission contract (MCV hull 666) at Richmond, Calif., on 3 June 1944 by the Permanente Metals Corp. Launched on 17 August 1944; sponsored by Miss Marie Tomerlin; and commissioned on 31 October 1944, Capt. Edward H. McMenemy in command.

Following her shakedown cruise, Talladega loaded cargo and passengers at San Francisco; got underway for Hawaii on 6 December; and arrived at Pearl Harbor on the 11th. The attack transport conducted amphibious landing exercises with elements of the 28th Regimental Combat Team (RCT), 5th Marine Division, to prepare for the assault on the Volcano Islands. She departed Pearl Harbor on 27 January 1945 and proceeded via Eniwetok to the Mariana Islands.

Talladega sortied from Saipan as a unit of Task Group 56.2, the Assault Group, on 16 February and arrived off Iwo Jima on the morning of the 19th, "D-day." After landing her troops, she remained off the beaches embarking combat casualties for six days before heading back toward Saipan.

Talladega was routed onward through Tulagi and New Caledonia to the New Hebrides. She loaded troops and equipment of the 165th RCT, 27th Infantry Division, at Espiritu Santo on 24 March and departed the next day. Her troops were part of the reserve for the invasion of Okinawa; and, after a stop at Ulithi, she arrived off that island on 9 April. She finished unloading her passengers and cargo by the 14th and returned, via Saipan, to Ulithi.

Talladega was subsequently ordered to the Philippine Islands and arrived at Subic Bay on 31 May. She remained in the Philippines, training elements of the Americal and 1st Cavalry Divisions for a projected invasion of Japan. However, before the operation began, Japan capitulated.

On 25 August, troops of the 1st Cavalry Division embarked, and the transport headed for Yokohama the next day. She disembarked her passengers there between 2 and 4 September and then returned to the Philippines to pick up soldiers of the 41st Infantry Division for transportation to Japan. The attack transport reached Kure, Honshu, on 5 October.

Talladega returned to Leyte on 16 October for provisions and fuel. The next day, she loaded 1,934 veterans at Samar and sailed for the United States. The ship arrived at San Pedro on 3 November and disembarked her passengers. She made three more round-trips to the Pacific to return troops: to Okinawa in December 1945, to the Philippines in April 1946, and to China in July. When Talladega returned to San Francisco in July, she began preparations for inactivation and assignment to the Reserve Fleet. She was placed out of commission, in reserve, on 27 December 1946.

The outbreak of hostilities in Korea on 25 June 1950 increased the Navy's need for active amphibious ships. Consequently, Talladega was recommissioned at Hunters Point, Calif., on 8 December 1951. She operated along the west coast until November 1952 when she embarked aviation personnel at San Francisco and steamed westward as a unit of Transport Division 12. The assault transport arrived at Yokosuka, Japan, on 29 November. She loaded men and equipment of the 1st Cavalry Division and headed for the Korean war zone.

Talladega arrived at Pusan on 14 December 1952, unloaded, and returned to Japan on the 18th. During the next nine months, the transport provided amphibious training for the United Nations forces in Japan and redeployed troops from one area in Korea to another. She operated in the war zone during each of the first seven months of 1963, but June. She worked along both coasts, transporting troops and supplies to such ports as Inchon, Koje Do, and Sokcho, before returning to San Diego on 16 August 1963.

During the next 12 years, the transport's operations along the west coast were broken by seven deployments to the western Pacific. In 1966, when United States forces assumed a combat role in South Vietnam, Talladega stood out of Long Beach on 27 April for duty with the 7th Fleet. After calling at Pearl Harbor from 2 to 6 May, she proceeded to Guam where she loaded cargo for Vietnam. She delivered the equipment and supplies at Danang on 30 and 31 May.

Following upkeep at Subic Bay, the attack transport moved to Okinawa to combat load the 3d Battalion, 7th Marines, for passage to Vietnam. On 1 July, Talladega joined Task Group 76.6, composed of Iwo Jima (LPH-2) and Point Defiance (LSD-31). Marines from the three ships were assault-landed at Qui Nhon and cleared Viet Cong forces from the mountains around Qui Nhon harbor by the 6th. They then reembarked in the ships which remained in the area until 22 July

From 16 to 26 August, Talladega participated in Operation "Starlight," landing marines 10 miles south of Chu Lai. On 12 September, she joined Task Group 76.3 which, in mid-September and early October, conducted the first two raids by a Navy-Marine Corps team in the Vietnamese conflict. On 11 October, the ship returned to Subic Bay and disembarked the marines and then proceeded to Okinawa to unload equipment. After calls at Yokosuka and Pearl Harbor, the transport arrived at Long Beach on 17 November 1966.

Talladega returned to the western Pacific from 14 January to 17 April 1966. During this period, she transported two loads of marines and their equipment from Okinawa to Chu Lai. In 1967, the transport was deployed from 21 July to 1 December. Elements of the 11th Infantry Brigade were transported to Hawaii in July; and, after calling at Guam, Talladega proceeded to Subic Bay. She arrived there on 27 August and began loading supplies for Vietnam. However, a change in orders sent her to Japan.

The transport arrived at Yokosuka on 7 September, loaded supplies for Operation "Hand Clasp," and headed for Korea the next day. She offloaded supplies at Pusan from 17 to 20 September and returned to Japan. On 12 October Talladega got underway for Vietnam.

Talladega arrived at Vung Tau on 19 October and loaded "Hand Clasp" supplies for delivery to Saigon. She offloaded the supplies between 26 and 31 October. The ship then began the return voyage to the United States. After calling at Hong Kong, Buckner Bay, and Pearl Harbor, she arrived at Long Beach on 1 Decemeber 1967.

Talladega was placed in a caretaker status for 18 months before being decommissioned in July 1969. In January 1969, she was redesignated LPA-208. On 20 October 1969, Talladega was transferred to the temporary custody of the Maritime Administration and berthed at Olympia, Wash. On 1 September 1971, the ship was transferred to the permanent custody of the Maritime Administration. In July 1972, the transport was moved to Suisun Bay where she remained until she was sold for scrapping in October 1982.

Talladega received two battle stars for World War II, two for Korea, and three for Vietnam.

|

Air Power |

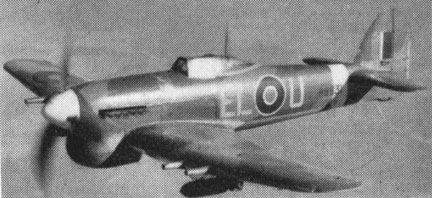

The Typhoons developmental life was so trouble that the entire project risked cancellations. The core of the problem were the untried powerplants that suffered from teething problems for wuite some time. Two prototypes were developed, the R-type Tornado equiped with the Vulture power plant and the N-type Typhoon equipped with the Napier Sabre. The Tornado prototype was eventually cancelled when the Vulture powerplant was abandoned. Production was delayed by the pressing need for Hurricanes and eventually the Typhoon's production was contracted to Gloster once development was complete.

The Typhoon began to enter service with Nos 56 and 609 squadrons at Duxford in September of 1941. Unfortunately the type still suffered problems, the Sabre powerplant proved to be unreliable and the rear fuselage had an annoying habit of coming apart. Once again the Typhoon risked cancellation but held on long enough for the problems to be resolved and a niche to be found. In late 1941 the Typhoon gained favour by demonstrating it's ability to catch Luftwaffe Fighter-Bombers that were making hit and run nuissance raids.

In 1943 the Typhoon's reputation grew as it descended on France and the Low countries and shot-up anything that moved. The type, now thoroughly developed and reliable became the premier ground attack aircraft of the RAF and proved particulayly suitable for operations from forward strips. Of the 3,330 Typhoons built, most (3,000 odd) had a bubble type canopy instead of the heavy framed canopy of the earlier type. The car style door was also deleted on these latter types. Further development of this aircraft led to the design of the Tempest

Specifications:

Origin: Hawker Aircraft Ltd

Manufacturer: Gloster Aircraft Company

Type: Originally heavy interceptor, later fighter bomber/ground-attack aircraft

Accommodation: Single pilot in enclosed cockpit

History: First flight (prototype) January 1938

First flight: 24th February 1940

First production delivery: 27th May 1941

Final production delivery: November 1945

Operational Equipment: Standard communications and navigational equipment, reflector gunsight, later sights for rockets and bomb-aiming.

Powerplant: Typhoon Mk IA/IB Napier Sabre IIA 2,180hp

Weights: Empty - 8,800lbs 4000kg / Loaded: 13,250lbs 6023kg

Dimensions:

Wingspan: 41ft 7in 12.67m

Length: 31ft 11in 9.73m

Height: 15ft 3 ½in 4.66m

Performance :

Maximum speed: 412mph 664kph

Initial climb: 3000 ft 914m/min

Service ceiling: 35,200ft 10,730m

Range: (with bombs) 510 miles 821km

Range: (drop tanks) 980 miles 1577km

Armaments:

Typhoon Mk IA: 12x 0.303-inch Browning machine guns

Typhoon Mk IB:

4x 20mm Hispano cannon,

+8x 60lb (27kg) rocket projectile,

Or 2x 500lb (227kg) bombs,

Later, 2x 1000lb bombs

All photos Copyright of:

http://WWII Tech and War Birds Resource Group

.......FALL IN to the FReeper Foxhole!

.......FALL IN to the FReeper Foxhole!

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.