|

Posted on 07/03/2003 12:04:19 AM PDT by SAMWolf

|

|

are acknowledged, affirmed and commemorated.

|

| Our Mission: The FReeper Foxhole is dedicated to Veterans of our Nation's military forces and to others who are affected in their relationships with Veterans. In the FReeper Foxhole, Veterans or their family members should feel free to address their specific circumstances or whatever issues concern them in an atmosphere of peace, understanding, brotherhood and support. The FReeper Foxhole hopes to share with it's readers an open forum where we can learn about and discuss military history, military news and other topics of concern or interest to our readers be they Veteran's, Current Duty or anyone interested in what we have to offer. If the Foxhole makes someone appreciate, even a little, what others have sacrificed for us, then it has accomplished one of it's missions. We hope the Foxhole in some small way helps us to remember and honor those who came before us.

|

|

In mid-December 1941, in the wake of Japan's massive land, sea, and air offensive in the Far East and its attack on Pearl Harbor, the Allies had no doubts about the need to support China fully to keep it in the war. China's forces would tie down Japan on the mainland. China would provide bases for attacks on Japan. In any event, Gen. Claire Chennault's China Air Task Force, the "Flying Tigers," had to be supplied.  Burma Road to China was closed by the Japanese conquest of Southeast Asia (from ILN 1942/01/10) Suddenly, in March 1942, supplying China became immeasurably harder. Japanese forces cut the Burma Road--the only overland path to China--and all land supply ceased. The Allies came back with a response unprecedented in scope and magnitude: They began to muster planes and pilots to fly over the world's highest mountain range. The route over the Himalayas from India to Yunnanyi, Kunming, and other locations in China was immediately dubbed "the Hump" by those who flew it. Though relatively short, the route is considered the most dangerous ever assigned to air transport. The reason is apparent from this description contained in the official Air Force history: "The distance from Dinjan to Kunming is some 500 miles. The Brahmaputra valley floor lies ninety feet above sea level at Chabua, a spot near Dinjan where the principal American valley base was constructed. From this level, the mountain wall surrounding the valley rises quickly to 10,000 feet and higher. "Flying eastward out of the valley, the pilot first topped the Patkai Range, then passed over the upper Chindwin River valley, bounded on the east by a 14,000- foot ridge, the Kumon Mountains. He then crossed a series of 14,000-16,000-foot ridges separated by the valleys of the West Irrawaddy, East Irrawaddy, Salween, and Mekong Rivers. The main 'Hump,' which gave its name to the whole awesome mountainous mass and to the air route which crossed it, was the Santsung Range, often 15,000 feet high, between the Salween and Mekong Rivers."  Pilots had to struggle to get their heavily laden planes to safe altitudes; there was always extreme turbulence, thunderstorms, and icing. On the ground, there was the heat and humidity and a monsoon season that, during a six-month period, poured 200 inches of rain on the bases in India and Burma. If the US was to conquer such obstacles, it would have to build an organization to ensure the smooth flow of planes, people, and supplies. The seeds of such an organization already existed. On May 29, 1941--fifty years ago this spring--the US Army had created the Air Corps Ferrying Command. Out of this small organization grew the US Air Transport Command, under the command of Maj. Gen. Harold L. George.  "Flying the Hump, Moonlight, CBI" by Tom Lea. Pilots flying this treacherous route kept Allied supply lines open. (Army Art Collection "It seems almost incredible," Gen. William H. Tunner remarked in his memoirs, "that up until three o'clock in the afternoon of May 29,1941, there was no organization of any kind in American military aviation to provide for either delivery of planes or air transport of materiel." When the Japanese closed the Burma Road, the US devised an initial plan that called for sending 5,000 tons of supplies each month over the Hump into China as soon as possible. American C-47s delivered the first, small load of supplies in July 1942. It was a meager beginning. If the resupply effort was to be greatly expanded, airfields would have to be built, pilots would have to be trained, and transports would have to be manufactured and ferried to the China-Burma-India (CBI) theater.  Generals Stilwell (left) and Merrill. (DA photograph) The air transport task in the CBI fell first to Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton, commander of Tenth Air Force. The Ferrying Command was to deliver seventy-five C-47s to the CBI, but some were diverted to support British forces in North Africa. Of the sixty-two that finally reached the theater, about fifteen were destroyed or lost, and many of the rest were out of service for long periods due to a shortage of parts and engines. It was obvious that the theater air commander should not be responsible for a supply route reaching from factories in the US to destinations in China. On October 21, 1942, Air Transport Command (ATC) officially took over the task. Operations under ATC began in India on December 1. The original small air transport unit was established as ATC's India-China Wing. As air transport activity increased, it became the India-China Division, comprising several wings. "Every drop of fuel, every weapon, and every round of ammunition, and 100 percent of such diverse supplies as carbon paper and C rations, every such item used by American forces in China was flown in by airlift," General Tunner said later.  Few aircraft are as well known or were so widely used for so long as the C-47 or "Gooney Bird" as it was affectionately nicknamed. Tonnage flown across the Hump increased slowly. Thirteen bases were established in India and six in China. Curtiss C-46s gradually replaced the Douglas C-47s and C-53s. Consolidated C-87s, the cargo version of the B-24, and some war-weary B-24s were added. In December 1942, 800 net tons were delivered to China. In July 1943, 3,000 tons were delivered. The target was 5,000 tons per month, but Gen. Chiang Kai-shek, the Chinese leader, wanted more. President Franklin D. Roosevelt personally ordered the target increased to 10,000 tons a month.

|

What looks like one more preserved C-47 Dakota is indeed a Russian airplane. During World War II, Russia acquired the license to built a derivative of the American Douglas DC-3 / C-47 transport. Reworked and named Lisunov Li-2, the Russian Dakotas first served in the war before entering civilian careers. Among the few preserved is Li-2 RA-73956 in Aeroflot polar markings (Salekhard, July 25/26 2000).

CCCP15010 Lisunov Li 2 at Monino 8.92.

Lisunov Li-2 (Russian DC-3)

Lisunov Li-2 (1945-1969)

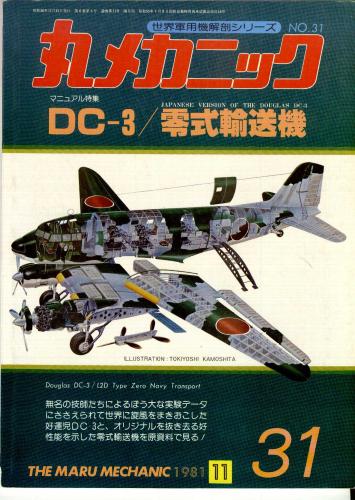

SHOWA L2D3(JPN VERSION OF DC-3)

Showa / Nakajima L2D2 "Tabby "

When the DC 3 came along, the Japanese immediately recognized its potential, especially since they had such great success with the DC 2. Great Northern Airways and the Far East Fur Trading Company (a Japanese military front company) purchased at least 21 DC 3s from Douglas between 1937 and 1939. The first Japanese DC3's were intended for KLM as PH ARA, but the order was canceled and these were allocated to Japan, arriving there on December 6, 1937. These transports were operated by Dai Nippon Koku and impressed into Imperial service during the war.

On February 24, 1938, a Japanese manufacturer, Mitsui (a subsidiary of Nakajima Hikoki), purchased the production rights and technical data to the DC 3 for $90,000. Unknown to the United States at the time, the sale was directed behind the scenes by the Imperial Japanese Navy (who was planning on using the type in the invasion of the East Indies). They saw the potential in the DC 3 to serve as a military transport. Mitsui and Showa Hikoki, another manufacturer, made many engineering revisions to take advantage of standard Japanese parts and raw materials. Japan also purchased and imported some machinery from the U.S. to speed up production.

The first Japanese produced DC 3 appeared in September 1939. By May 1941, the fifth DC 3 left the Showa factory, this one using the last Douglas built fuselage. By July 1941, the factory was producing one DC 3 transport per month, far short of the one airplane per day demanded by the Imperial Japanese Navy. Finally by 1942, the production quota was reached. The Allies code named the L2D2s "Tabby."

Although ostensibly purchased for civilian use, the Japanese DC 3s were given a Navy designation L2D2 (L transport, 2 second Navy type). L2D1 became the designation for imported DC 3s. The Japanese built eight separate sub types in two basic configurations, straight airline type, and cargo planes. Japan modified the transport design for easier production. In addition, they replaced the Pratt & Whitney 1,000 hp engines they imported with 1,000 hp Mitsubishi Kinsei 43 radial engines.

After two years of manufacture, Nakajima had built 71 C 47 type aircraft (designated L2D2 Navy Type 0 Transport Model 11) and switched to manufacturing combat aircraft. Meanwhile, Showa built 416 DC 3 type aircraft, including 75 cargo versions with the "barn door," and reinforced floor (designated L2D2 1). The first Japanese military version with wide cargo doors, remarkably similar to the U.S. C 47, appeared about the same time as the C 47. There are strong suspicions that it was a copy, and not the product of an independent design. The Japanese manufactured 75 cargo versions of the DC 3.

Japan's civilian DC 3 was similar to the U.S. version, but the military version was noticeably different. The main production version of the Japanese DC 3 appeared in four variants; the L2D3 was a personnel transport powered by 1,300 hp Kinsei 51 radials, the L2D3G, also a personnel transport but with Kinsei 53 radials, the L2D3 1 and L2D3 1a were cargo transports powered by Kinsei 51s and 53s respectively. Some obvious differences were the three extra windows behind the cockpit, larger engine cowlings on the 1000 hp Kinsei 43 engines, and larger spinners on the propellers. They moved the cockpit bulkhead back 40 inches so all four men were in one compartment. The military version included a 13mm machine gun turret in the navigator's dome and a 7.7mm machine gun in the rear window on each side of the fuselage. This aircraft was designated L2D4 Navy Type 0 Model 32.

Because of shortages of strategic materials, Japan redesigned less critical components in the DC 3s and replaced the metal versions with wood. These parts included rudder, stabilizer, ailerons, fin, elevator, and entrance door. As many as 30 transports with these wooden parts entered service apparently with satisfactory results. The success of this modification and the growing need for metal forced Japan to design an all wooden version of the DC 3, which they designated the L3D5. The Showa facility was to have produced this new version in quantity but the government shifted the priority of the factory to building bomber and suicide aircraft.

It is not certain how many wooden Gooney Birds were built, but the occupation troops found at least one all wooden C 47. The all wood Gooney Bird was a static test fuselage but preparations were underway to mount two 1,560 hp Kinsei 62 engines on the airframe. Expert opinion is that it required the larger engines to lift the heavier structural weight. It never flew, and went to the scrap pile with most of Japan's DC 3s. It is believed, however, that a few Japanese versions went to the Chinese Air Force. After the war, inspection and flight testing of these later versions showed that because of Japan's use of plywood on fairings, tail cone, surface controls, and doors, it out performed the U.S. version. The 30 part wood, part metal versions were sent to the scrap pile.

Good thread and graphics, Sam.

How about you?

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.