|

are acknowledged, affirmed and commemorated.

|

Posted on 01/21/2003 5:35:58 AM PST by SAMWolf

|

are acknowledged, affirmed and commemorated.

|

|

|

|

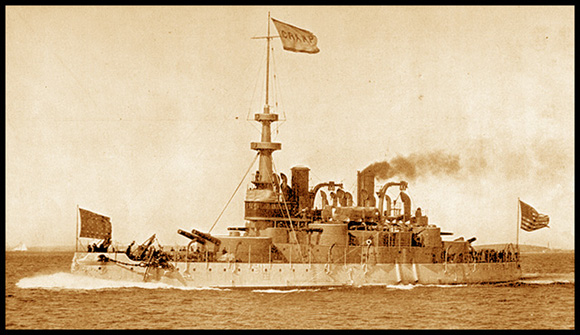

Birth of the Modern US Navy If the prospects for war with Spain had been a foregone conclusion for months, so too was the predicted outcome of such a conflict. The Spanish fleet, while still large, was an aging fleet that no longer reflected the luster and might that had made the terms "Spanish" and "Armada" synonymous. Despite the fact that many ships of the enemy fleet were constructed of steel, as were the newer warships of the U.S. Navy, they were no match for the modern guns of the American sailors. Author Sherwood Anderson had his own unique perspective of America's coming battles with Spain. He said it would be "Like robbing an old gypsy woman in a vacant lot at night after a fair."  The three-day run across the South China Sea was made, as one Naval lieutenant later reported, "As directly and with as little attempted concealment as if on a peace mission. Lights were carried at night and elecric signals freely exchanged; but gruesome preparations were going on within each ship. Anchor chains were hung about exposed gun positions and wound around ammunition hoists; splinter nets were spread under boats; bulkheads, gratings and wooden chests were thrown overboard; furniture was struck below protective decks; surgical instruments were overhauled and hundreds of yards of bandaging disinfected. The sea was strewn for fifty leagues with jettisoned woodwork unfit to carry into battle." (Lt. John Ellicott) Once his fleet had put to sea, Admiral Dewey ordered the men to muster on each ship to hear a reading of the proclamation issued five days earlier by General Basilio Augustin Davila, the Spanish governor-general of the Philippine Islands. In that proclamation Davila asserted that, "The North American people...have exhausted our patience and provoked war...with their acts of treachery. "A squadron manned by foreigners, possessing neither instruction nor discipline, is preparing to come to this archipelago with the ruffianly intention of robbing us of all that means life, honor and liberty. Pretending to be inspired by a courage of which they are incapable, the North American (U.S.) seamen undertake as an enterprise capable of realization, the substitution of Protestantism for the Catholic religion you profess, to treat you as tribes refractory to civilization, to take possession of your riches as if they were unacquainted with the rights of property, and to kidnap those persons whom they consider useful to man their ships or to be exploited in agriculture or industrial labor." When the entire text of General Basilio's March 23rd proclamation had been read, the officers of each American ship informed the crew that their destination was the Philippine Islands to "capture or destroy the Spanish fleet." The cheers of the sailors and Marines echoed across the South China Sea as the United States Navy prepared for its first major foreign test as a world power. As morning dawned on April 30th, Admiral Dewey's fleet sighted the coastline of the largest of the Philippine islands, Luzon. The United States Navy had finally arrived, prepared for war. First however, they had to locate the enemy fleet. Spanish Admiral Patricio Montojo y Pasaron was no novice at sea, and among the more than 700 islands of the archipelago there were literally thousands of small coves that would hide his vessels.  The logical location for finding the enemy would be somewhere in the vicinity of Manila Bay, a large inlet near the Philippine capital city, midway on the western coast of Luzon. Arriving at Luzon eighty miles north of Manila Bay, Dewey dispatched his warships Boston and Concord to reconnoiter the smaller bays and inlets as the remaining seven vessels slowly continued southward towards Manila Bay. The Boston and Concord found no sign of the enemy fleet, then proceeded to enter Subic Bay at the northwest edge of the Bataan peninsula. Again they found no sign of the enemy vessels, and turned to rejoin the fleet. As they departed the bay they met the Baltimore, recently dispatched ahead of the rest of Dewey's warships to meet them. (Had the reconnaissance occurred one day earlier, the Boston and Concord would have steamed directly into the Spanish fleet. Within the previous 24 hours Admiral Montojo had sailed his warships out of Subic Bay after a 4-day stay, opting to enter the shelter of the larger Manila Bay.) As the sun began to set on the evening of April 30th, Admiral Dewey's full fleet of 7 warships and 2 transports had marshaled outside Subic. He ordered the commanding officers of each ship to join him on the flag ship Olympia, where he outlined his plans. For the men of the United States Navy, it would be a long night. Manila Bay is a large inlet on the western coast of Luzon, nearly twenty miles wide and twenty miles deep. Entrance to the bay is only achieved through a narrow passageway less than ten miles across, and broken up by the tadpole shaped fortress island of Corregidor, and the smaller islands of Caballo and El Fraile. At the north end of the entrance is the Bataan Peninsula and the city of Mariveles. With heavy guns placed on fortifications at Mariveles and Corregidor, and with additional batteries on the two smaller islands and the southern tip of the entrance, an enemy attempting to enter Manila Bay would be subject to an intense cross-fire from at least five batteries. At the north end of a small peninsula just southwest of the capitol city sat the Cavite arsenal, as well as additional fortifications on Sangley Point. Admiral Montojo chose to anchor his ten warships and their transports just outside the city of Manila, knowing that before an enemy could attack him, they would first have to run the gauntlet of shore batteries at the harbor's entrance. Scattered throughout the smaller coves and river inlets to the harbor he had another 20 or more small river boats. It was a perfect place to hide or, should an enemy dare to run the gauntlet, to stand and fight.  Aboard the Olympia, Admiral Dewey was planning to do just that. As the ship's band played "There'll be a hot time in the old town tonight," the American commander explained his order of battle. The young moon would provide just enough light for the lead ship to spot the island of Corregidor and the entrance to Manila Bay. By midnight however, the moon would set to provide a darkened passage for his fleet as they ran the enemy gauntlet. If all went well, when morning dawned, he would find and destroy the Spanish fleet. At 7:30 that evening, the commanders each having returned to their respective warships, Admiral Dewey began leading the convoy towards Manila Bay in his flagship. Cruising at 8 knots, strung out behind him at intervals of 400 yards, was a single line of American Naval power: Baltimore, Raleigh, Petrel, Concord, Boston, McCulloch, Zafiro, and Nanshan...in that order. Each ship traveled under complete blackout conditions, save for a single light aft. Even that light was shielded so as to be hid from the periphery. Only the ship directly behind could see its faint glow, as the silent warships crept in a single line towards the battlefield. At 10:40 the lights of the enemy encampment at Corregidor came into view, and the men of the American war ships were ordered to stand by their guns. Within the half hour the "Olympia" entered the Boca Grand, the larger of two channels entering Manila Bay. In the darkness the dull, gray ships silently crept forward, young and untested soldiers crouching in hushed anxiety near their guns. None would sleep on this night. By 11:30 the fleet was committed to its dangerous course when the night was lit by a rocket from Corregidor. Young sailors held their breath as they awaited the crash of enemy guns that was destined to follow. None came. The American fleet had not yet been spotted and slowly continued onward. A short time later the lights at Corregidor, Caballo Island and on the San Nicolas Banks were extinguished for the night.  Midnight and total darkness fell over the passageway, and then came the first sounds of enemy fire. At last the shore batteries had detected the passage of the American battleships, and shells began to rain over the convoy. The first rounds came from the south shore near Punta Restinga, followed by the shells from the batteries at Caballo and El Fraile. The Raleigh and Concord briefly returned fire, but the Americans quickly noted that the enemy shells were falling far over their heads. In the darkness the ships were still nearly invisible as they ran the gauntlet. Shortly after four o'clock on the morning of May 1st, the Olympia was well into the harbor, the other American ships behind her and prepared for battle. Skill and daring had enabled the 9 vessels to negotiate the passageway, thought to have been mined and directly under the shore batteries of the enemy, to find and sink the Spanish fleet. Twenty miles distant Admiral Dewey could see the lights of Manila. In front of the capitol city in a line northward from Sangley Point was anchored ten warships of Admiral Montojo. Concealment was no longer important, the Spanish now knew the Americans had arrived. Admiral Dewey's flagship became a beacon of flashing signal lights as he organized his ships for the battle that would come with dawn. It was not until two o'clock in the morning that Admiral Montojo had been awakened to be informed that the Americans had entered the bay. He was stunned. The thought that the American commander would make the three-day trip from China and, on his first night upon arrival and without reconnaissance, dare to run the batteries and probable mine fields to enter Manila Bay in the dead of night, had never crossed his mind. Be that as it may, the Americans had arrived, and Montojo ordered his ships to raise steam. All his officers who had gone ashore to be with their families were awakened and called back to their ships. At 4:00 A.M. coffee was served to the officers and men of Admiral Dewey's fleet. Three vessels of the reserve squadron were sent northward to lay to, while Dewey's remaining six ships continued their course towards Manila. At 5:05 A.M. the Stars and Stripes were unfurled from each of the war ships and Dewey gave the command to "Prepare for general action." Ten minutes later the enemy shore batteries at Sangley Point opened fire. The American ships returned fire, then turned towards the ships of Admiral Montojo.  Within minutes the early morning air was filled with the thunder of heavy guns, and geysers of water shooting heavenward as the enemy shells began falling around the American ships. Dressed in his crisp white Naval dress uniform, Admiral George Dewey stood on the bridge of his flagship "Olympia". In the preceding hours he had done the unthinkable, navigating the Boca Grand to find and meet the enemy. As the smell of smoke filled the air and the shells of the enemy erupted around his fleet, Dewey led the way into battle. At 5:40 A.M. he turned to the Captain Charles V. Gridley of his flagship, the USS Olympia and said: "You may fire when ready."

|

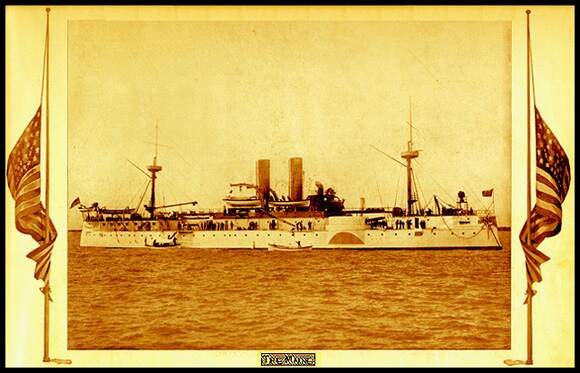

Here's Maine from Starboard:

Rank and organization: Chief Carpenter's Mate, U.S. Navy. Born: 26 November 1853, Gross Katz, Germany. Accredited to: California. G.O. No.: 13, 5 December 1900. Citation: On board the U.S.S. Petrel, Manila, Philippine Islands, 1 May 1898. Serving in the presence of the enemy, Itrich displayed heroism during the action.

Dewey beat `em and how!

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.