|

Posted on 01/19/2005 9:47:42 PM PST by SAMWolf

|

|

are acknowledged, affirmed and commemorated.

|

| Our Mission: The FReeper Foxhole is dedicated to Veterans of our Nation's military forces and to others who are affected in their relationships with Veterans. In the FReeper Foxhole, Veterans or their family members should feel free to address their specific circumstances or whatever issues concern them in an atmosphere of peace, understanding, brotherhood and support. The FReeper Foxhole hopes to share with it's readers an open forum where we can learn about and discuss military history, military news and other topics of concern or interest to our readers be they Veteran's, Current Duty or anyone interested in what we have to offer. If the Foxhole makes someone appreciate, even a little, what others have sacrificed for us, then it has accomplished one of it's missions. We hope the Foxhole in some small way helps us to remember and honor those who came before us.

|

|

When an overzealous Union captain stopped and searched the British vessel Trent, a full-blown diplomatic crisis erupted between the United States and Great Britain. Interested Southerners watched with glee.  As U.S. Navy Lieutenant D.M. Fairfax stood in the bow of a bobbing whaleboat at midday of November 8, 1861, he was faced with a dilemma. Ahead loomed the bulk of the British mail steamer Trent. His orders were to remove--forcibly if necessary--two Confederate agents on their way to London. He was also to seize the vessel as a prize of war. Either act, he believed, could lead to war between the United States and Britain. Yet the instructions received from his commanding officer were explicit. Fairfax's confusion stemmed from several factors, most notably Britain's declaration of neutrality in May 1861 and its recognition of the Northern and Southern states as formal belligerents. Such a dictate opened British ports to Confederate shipping as well as Northern. Likewise, British munitions and supplies could be transported by Union or Rebel vessels to North American ports.  Captain Charles D. Wilkes To many observers and politicians in the North, however, London's declaration was but a short step away from recognizing the Confederate states as a sovereign nation. The Richmond government banked on the hope that both France and England could be induced to accept the Confederacy into the family of nations because of the need for Southern cotton by European mills. Prior to the Civil War, England and Continental Europe imported from 80 to 85 percent of its cotton from the South. Nearly one-fifth of the British population earned its livelihood from the cotton industry, while one-tenth of Britain's capital was invested in it as well. There was good reason for the South to court the European governments. Confederate President Jefferson Davis assigned a pair of trusted political cronies to represent the South in London and Paris. James M. Mason, a former senator from Virginia, had gained experience as the chairman of the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee. His assignment as minister to Britain was not to beg "for material aid or alliances offensive and defensive but for. . . a recognized place as a free and independent people."  John Slidell Sixty-eight-year-old John Slidell was to transact diplomatic business with France. A wily politician, Slidell had served as a Louisiana senator and had only minor diplomatic experience in previous dealings with Mexico. He was, however, fluent in French. Both Mason and Slidell hurried to Charleston, S.C., to gain passage on the fast blockade runner Nashville. Accompanying them were two secretaries, James E. Macfarland and George Eustis, as well as members of Slidell's family. When they reached Charleston in early October 1861, they found several Union warships blockading the harbor just beyond the range of Confederate coastal defense guns. Though armed, Nashville was too weak to provoke a battle with Yankee cruisers and usually relied on speed to sneak past picket ships. Realizing the dangers of trying to run the blockade, Mason and Slidell opted for going overland through Texas and into Mexico, where they hoped they could book passage on a British ship to take them to London. Before they could attempt the journey, however, the captain of a shallow-draft coastal packet, Gordon, offered to take the diplomats to Cuba, where British vessels regularly docked.  James M. Mason, Confederate Envoy to England Rain squalls buffeted Charleston as Gordon slipped from her quay just after midnight on October 12. The little ship, packed with coal and passengers, threaded its way through shallow waters where the deep-draft Nashville could not have gone. The storms and darkness served as perfect cover as the Rebels slid past Federal blockaders and steamed toward the open sea. "Here we are," Mason wrote gleefully, "on the deep blue sea; clear of all the Yankees. We ran the blockade in splendid style." To confuse prowling Federal cruisers, Gordon's name was changed to Theodora. The packet sailed into Nassau, in the Bahamas, where the Confederates had hoped a British vessel might be docked. When they discovered that English mail ships could be anchored at Cuba, Theodora did an about-face and steamed southwest.

|

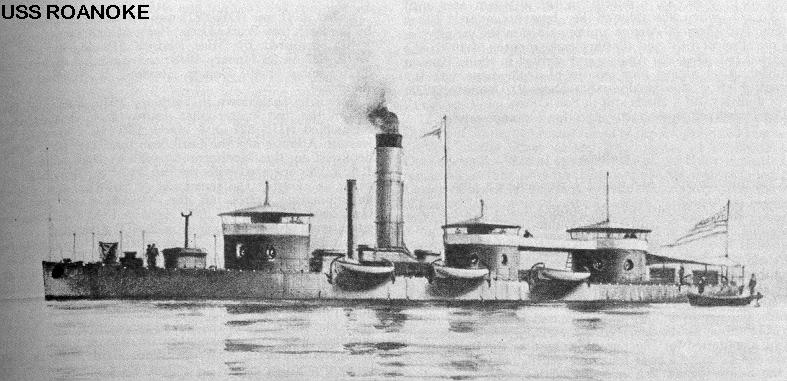

Displacement: 4,395 tons

Displacement: 4,395 tons Dimensions: 265 x 53 x 22 feet/80.77 x 16.15 x 6.7 meters

Propulsion: Penn trunk steam engines, 4 boilers, 440 hp, 1 shaft, 6 knots

Crew: 350

Armor: Iron: 3.5-4.5 inch sides, 1.5 inch deck, 11 inch turrets

Armament: Three dual turrets, as follows:> Forward Turret: 1x15 inch Dahlgren smoothbore, 1x8 inch Parrot MLR

Center Turret: 1x15 inch Dahlgren smoothbore, 1x11 inch Dahlgren smoothbore

Aft turret: 1x11 inch Dahlgren smoothbore, 1x8 inch Parrot MLR

Concept/Program: One of the largest monitors of the Civil War era, and the only one to mount three turrets. Was converted from the steam frigate Roanoke; prior to conversion the ship was sister to USS Merrimack (later CSS Virginia). Although not usually considered as a seagoing ship, she was intended as the first seagoing monitor in US service, but design flaws prevented her employment in this role. Was not a success.

Design: Was not an Ericsson design. The wooden frigate was razeed (cut down) and the remaining freeboard armored; three turrets were fitted. A fourth turret had been planned, but the weight could not be accommodated. Pilothouses were fitted on two turrets; there was a tall funnel, and possibly a hurricane deck, but no other superstructure.

The armament was oddly distributed, but in total amounted to two each 15 inch Dahlgrens, 11 inch Dahlgrens, and 8 inch Parrots.

The wooden hull was too weak for the weight of the armor and turrets, and the stern was damaged when the ship was re-launched.

She had high freeboard (for a monitor), but rolled heavily and was generally unseaworthy.

Operational: Due to her unseaworthiness, she was confined to harbor defense duties at Hampton Roads, and saw no action.

BTTT!!!!!!!

Very cool. What was it like?

There was something awesome about the steel doors with giant knocker rings at Justice.

Every corner had a lone dude in an overcoat with a [coded] lapel pin.

The crowd from DENSA has not progressed a micron from the days of Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh, et cetera.

I enjoyed the Nixon Library in 1998. There is a section of the Berlin Wall, concrete with protruding rebar, vintage graffitti.

Cuba would be free had Daley and LBJ not stolen the 1960 election.

South Vietnam would be free had Nixon not been hounded out of office--after all, compared to Clinton donors Schwartz and Armstrong faxing the ChiComs 200 pages of our missile guidance, what is a file on John Dean's wife?

Abbie Hoffman committed suicide not long after my visit to the library.

John Kerry, take note.

Tom Lantos: "Aht least Ahbee Hawffmann hahd thee deecency too coe-mit soo-ee-side."

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.