Skip to comments.

Out of the Blue: Finding Buddy

Virginian Pilot ^

| 24 June 2004

| JOANNE KIMBERLIN

Posted on 06/24/2004 4:05:52 AM PDT by csvset

Out of the Blue: Finding Buddy

|

|

|

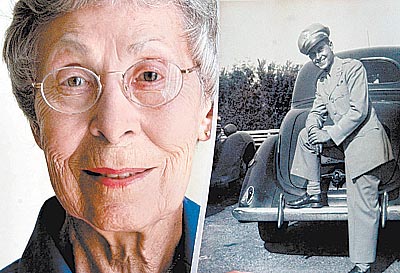

Fern Lord holds a photograph of her brother, Buddy, who was lost in a B-24 crash in World War II. When told that remains found in New Guinea are likely those of her long-lost brother, Lord said, “I know it sounds strange, but after what we’ve been through, that would be a happy ending.We want to give him a proper burial before it’s time for ours.” JOHN H. SHEALLY II/THE VIRGINIAN-PILOT

|

By JOANNE KIMBERLIN, The Virginian-Pilot

© June 24, 2004

SUFFOLK — Fern Lord is 81.

She was 21 when her brother Buddy disappeared.

For nearly 60 years, there was only silence.

Then one day, a hunter in New Guinea stumbled across a rusty, vine-strangled heap on a mountainside in the jungle. Two months ago, a lab tech knocked on Fern’s door in Suffolk and extracted a vial of blood from a vein in her arm.

If the DNA matches, Fern and her 84-year-old sister may finally be able to bury their brother, before it’s time to be buried themselves.

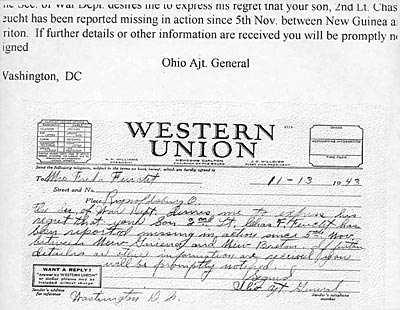

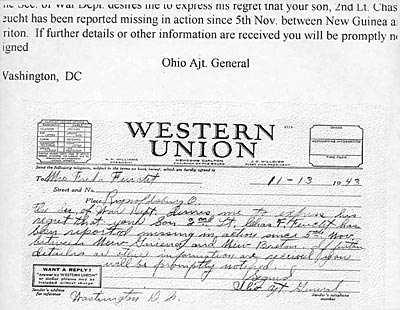

In November of 1943, both of Fern’s brothers were fighting the Japanese in the South Pacific. Only her mother and father were home the day the Western Union man walked into the kitchen of the family’s dairy farm.

Everyone knew everyone in Reynoldsburg, Ohio, a small town east of Columbus. The telegram man kept his eyes on the floor as he held out the dreaded pale yellow piece of paper.

“I’m so sorry I had to bring this,” he choked before retreating out the door.

Slowly, Fern’s father unfolded it and read. “The Secretary of War … express his regret … your son … missing in action …”

Her oldest brother, Charles “Buddy” Feucht, a bombardier aboard a B-24 Liberator, had disappeared, his plane lost somewhere between New Guinea and New Britain – faraway islands Fern wasn’t even sure she could find on a globe.

What terrible thing had happened to Buddy so far from home? He belonged in Reynoldsburg, where he had grown up playing along the creeks, delivering the morning pa per and showing his prize pigs at the county fair. He loved a hometown girl he planned to marry.

But when war came, Buddy trooped off, eager to serve his country, itching for a crack at the enemy. Now, at 24, he was gone.

Fern’s mother began to sob. Her father’s face was blank.

“Daddy told me later that he did his crying out in the fields,” Fern said, “alone.”

The telegram had promised more details as they were learned. None came. In the void, the Feucht family hoped, and despaired.

Maybe Buddy was stranded on a deserted island, living like Robinson Crusoe. Maybe he’d been captured by the Japanese. Maybe he was dead.

When the war ended in 1945, sons returned to Reynoldsburg. Fern’s younger brother came home, but not Buddy. For months, her mother pored over newspaper stories of liberated prison camps overseas. With a magnifying lens, she scoured the photos of joyful faces rushing the gates. Buddy’s was never among them.

Sometime that year, a car carrying a handful of strangers pulled up to the farmhouse. Buddy’s war mates had come to pay respects to his family.

Buddy’s plane, they said, had been bringing up the rear of a bomber formation hunting Japanese ships north of Australia at night. In that part of the world, flying conditions were almost as deadly as the enemy. Planes ran a gantlet of rainforest-cloaked islands, where jagged limestone mountains jutted tall enough to churn their own, often-violent weather systems.

A thunderstorm whipped the formation as it headed back to its base on New Guinea.

Buddy’s plane radioed its intent to peel away for a look-see.

“They indicated that they’d found something big,” Fern said.

Swallowed by the darkness, the plane was never seen again.

That’s the last the family ever heard about Buddy. Life went on, with marriages, careers, grandchildren. Fern Feucht became Fern Lord, marrying a man whose job eventually brought the couple to Hampton Roads.

“But mother and daddy,” Fern said, “they never locked their doors again. Just in case Buddy came back in the middle of the night or when no one was home. They wanted him to be able to walk right into the house, like he used to.”

In time, Buddy evolved into a family legend, a topic at reunions, a mystery for an ever-growing brood of cousins to periodically ponder.

For Fern, one part of the puzzle was solved in 1969.

“My mother was dying and I was sitting by her hospital bed,” Fern said. “Right before she went, she looked up and said, 'Oh, hello Buddy.’ That’s when I knew for sure that he was on the other side.”

The decades kept going, eventually claiming Lord’s father, then a sister, then her brother. Only Fern and another sister, Mary, still in Reynoldsburg, remain alive. The rest died without an answer about Buddy.

Fern admits she gave up long ago.

“I never thought we’d find out the truth.”

She didn’t know that, all these years later, someone was out there, still looking for Buddy.

Hunter turns up clues

A human bone and a handful of metal ID tags arrived at the U.S. Embassy in Papua New Guinea in the spring of 2002. The hunter who delivered them also reported the tail number and location of the old plane he’d found.

The embassy contacted the U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii. The lab’s main mission since the Vietnam war has been to locate, identify and bring home the remains of America’s fallen soldiers.

With 88,000 still unaccounted for – 78,000 from World War II alone – the lab works to fulfill a simple commitment from a nation to its war dead: a decent burial.

Advances in technology and science, particularly in the field of DNA, have paid off big for the lab in recent years.

The remains of more than 1,100 service members have been returned to their next of kin, including one who was long interred in the hallowed Tomb of the Unknowns at Arlington National Cemetery.

New Guinea, located in the thick of some of World War II’s most brutal action, has been fertile ground for the lab. Old plane wrecks in places like Vietnam tend to be heavily scavenged by locals. In New Guinea, the natives view the twisted hulks as sacred tombs, leaving them virtually untouched.

The slower speed of old battle planes also makes a difference. World War II crashes, though violent enough to kill, often left fuselages intact, which improves the odds of finding a recognizable body inside.

Tough terrain is the biggest challenge in the tropical, triple-canopy climate of New Guinea. The hunter’s find was located on a rugged mountainside 10,800 feet above sea level. An expedition to such a place wouldn’t be launched lightly.

Lab historians went to work, tracing the tail numbers through military archives.

From there, they found the crew list and details of their mission.

In September of 1943, Buddy’s nine-man crew finished training at Langley Field.

In late October, they landed in New Guinea, assigned to the Super Snoopers, tasked with flying night anti-ship missions by radar. Their fateful flight came Nov. 5, just 15 days after their arrival on the island.

Records say the crew spotted a Japanese convoy of 10 ships and shadowed it for four hours. With fuel running low, they began dropping bombs, scoring three direct hits and destroying at least one ship.

At 1:20 a.m., a radio message indicated the B-24 was returning to base. Then it vanished. A search plane sent up at dawn found no trace.

Sixty years later, the hunter’s discovery solved the mystery. Buddy’s plane had slammed into the infamous Owen Stanley Range, the treacherously spiked backbone of New Guinea, and the graveyard of several hundred Allied aircraft.

The area’s dense growth and steep canyons still hide the remains of some 1,600 World War II airmen.

Lab personnel made two survey trips to the B-24 site before mounting a full-scale recovery mission in May 2003. Tragedy struck when a helicopter carrying a lab team to the mountain crashed into the ocean. The pilot drowned, trapped in his harness. The mission was suspended.

In August, an 11-member team returned to New Guinea. Made up of forensic anthropologists, military undertakers, a bomb expert, medic and photographer, the group set up a base camp and spent 35 days excavating the wreck.

Inside the shattered cockpit, they found more bones, teeth, ID bracelets and other personal items. A clock on the dash had stopped at 1:21 a.m., one minute after the plane’s final radio transmission.

The remains were ferried back to Hawaii, where the lab began sorting and identifying. Given the right body parts, old dental and medical records can often answer the question of who’s who. If not, technicians can cut a small section of bone, map its DNA and match it to a relative of the deceased.

Family, however, can be tough to find 60 years after the fact. Buddy’s parents were listed in his personnel file, but both were dead. With his only brother gone as well and his surviving sisters married, a trace on the family’s last name led nowhere.

As far as the lab could tell, there was no one left who cared about Buddy.

Niece searches on Internet

Dawn Lee is one of Buddy’s nieces , and she’s always been fascinated by her uncle’s story. She’s 46 and a library researcher at a public school in West Bath, Maine.

A telegram dated Nov. 13, 1943, informs the Feucht family that Buddy has been reported missing in action somewhere between New Guinea and New Britain. Courtesy photo.

The Internet is one of her favorite research tools, and over the years, she’s punched Buddy’s name on her keyboard dozens of times just to see if anything turned up. It never did.

Lee tried again in December. A newspaper story popped up about an old bomber being found in New Guinea. The names of its crew were not included.

“I didn’t think much about it,” Lee said, “except to imagine how incredible it would be if that was Uncle Buddy.”

A few months later, Lee was at school, winding up a lesson in online research. Buddy’s story seemed like a good way to inject some excitement to the subject.

With students watching, Lee typed Buddy’s name into her computer. A Web site came up she’d never seen before. It specialized in old Pacific wrecks.

A few quick clicks and suddenly Lee was staring at a photograph of her Uncle Buddy, his crew and his plane, along with an brief explanation of the wreck’s recovery.

“I started to cry,” Lee said. “My students kept asking me if I was OK. I couldn’t even talk.”

Word raced through the family down to Hampton Roads. A son-in-law who lives in Chesapeake called the lab in Hawaii.

“Sometimes,” said lab spokesman Ken Hall, “that family phone call is the one thing that puts us back in the game.”

In April, both Fern Lord and her sister were asked for blood samples. Hall wouldn’t say if relatives of Buddy’s crewmates have been located. He did say that Buddy’s family is the only one to provide DNA so far.

Results, however, can take up to a year.

The lab is chronically underfunded and contantly shuffling cases, based on priority directives from above.

“We don’t mean to be pushy,” Fern said. “But let’s face it. We’re old. We might not have a year to wait.”

If and when they get a piece of Buddy back, Fern and her sister plan to bury him beside their parents in Reynoldsburg.

“It’ll bring the circle to a close,” Fern said. “Sometimes I think that’s why we’ve been allowed to live this long.”

The discovery in New Guinea has brought great comfort to Fern and her sister.

“I go for a walk at 5:30 every morning,” she said. “I always fix on a star and I use it to greet my mother and father and other relatives and friends. I know where they are and it’s my way of communicating with them. But Buddy has always been nowhere. Until now.

“He’s finally found a place in my mind. And that’s a real warm feeling after all these years.”

Reach Joanne Kimberlin at 446-2338 or joanne.kimberlin@piloton line.com

TOPICS: VetsCoR

KEYWORDS: armyaircorp; b24; dna; newguinea; rip; wwii

RIP Buddy.

1

posted on

06/24/2004 4:05:53 AM PDT

by

csvset

To: csvset

Bump. Welcome Home Buddy.

2

posted on

06/24/2004 11:36:57 PM PDT

by

SAMWolf

(Imagination is the only weapon in the war against reality)

To: csvset; JulieRNR21; Vets_Husband_and_Wife; Cinnamon Girl; Alamo-Girl; Bigg Red; jwalsh07; ...

2Lt. Charles “Buddy” Feucht, WELCOME HOME!

Click on the image to visit the tribute page±

to visit the tribute page±

"The Era of Osama lasted about an hour, from the time the first plane hit the tower to the moment the General Militia of Flight 93 reported for duty."

Toward FREEDOM

Toward FREEDOM

3

posted on

06/29/2004 11:54:27 PM PDT

by

Neil E. Wright

(An oath is FOREVER)

To: Neil E. Wright

“My mother was dying and I was sitting by her hospital bed,” Fern said. “Right before she went, she looked up and said, 'Oh, hello Buddy.’ That’s when I knew for sure that he was on the other side.” Welcome Home Buddy.

Thanks for the ping Neil.

4

posted on

06/30/2004 12:34:29 AM PDT

by

snippy_about_it

(Fall in --> The FReeper Foxhole. America's History. America's Soul.)

To: Neil E. Wright

What a wonderful story. Sitting here with tears dripping onto the desk. Thank you Neil.

Welcome home, Buddy and thank you for your sacrifice so that my son could be raised in FREEDOM!!

5

posted on

06/30/2004 4:13:02 AM PDT

by

dixie sass

( Claws are sharp and ready for use!)

To: The Mayor; Eagle9; LadyX; WVNan; chesty_puller; Bigun; jenx; Memother; Billie; diotima; ...

6

posted on

06/30/2004 4:21:34 AM PDT

by

dixie sass

( Claws are sharp and ready for use!)

To: Neil E. Wright

To: Neil E. Wright; csvset

Welcome Home, Buddy.

Heart-warming to be reminded once again that we value our own, regardless of time and regardless of distance. How can anyone not love this great country and those that defend it?

Thanks for the ping, Neil.

8

posted on

06/30/2004 7:48:42 AM PDT

by

Eastbound

To: Neil E. Wright

9

posted on

06/30/2004 11:36:52 AM PDT

by

firewalk

To: wagglebee

Ping. I saw the update that you posted. Here's the article for 2004.

RIP Buddy

10

posted on

03/31/2006 5:54:49 PM PST

by

csvset

To: csvset

I didn't remember seeing it in the Pilot back then, I must have been out of town or something. I did go back and read it today.

11

posted on

03/31/2006 5:56:49 PM PST

by

wagglebee

("We are ready for the greatest achievements in the history of freedom." -- President Bush, 1/20/05)

Disclaimer:

Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual

posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its

management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the

exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.

FreeRepublic.com is powered by software copyright 2000-2008 John Robinson