|

Posted on 02/18/2004 12:00:09 AM PST by SAMWolf

|

|

are acknowledged, affirmed and commemorated.

|

| Our Mission: The FReeper Foxhole is dedicated to Veterans of our Nation's military forces and to others who are affected in their relationships with Veterans.

Where the Freeper Foxhole introduces a different veteran each Wednesday. The "ordinary" Soldier, Sailor, Airman or Marine who participated in the events in our Country's history. We hope to present events as seen through their eyes. To give you a glimpse into the life of those who sacrificed for all of us - Our Veterans.

|

|

"Swoose" Among the many World War II aircraft preserved at the National Air and Space Museum, "The Swoose" is one of the few that actually flew combat missions. This airplane remained in service from the beginning to the end of that conflict, first as a bomber and later as a VIP transport. The history of the Flying Fortress begins in 1935 when U. S. Army airpower advocates tested the first multi-engine airplanes capable of strategic bombing operations. Doctrine supporting this mission had been evolving since the late 1920s. For a time, planners thought that long-range bombers should defend the American coast, and bomb targets on land.  After the mid-1930s, the mission focused more on precision, daylight bombing of strategic land targets deep behind the battlefront. In August 1935, Boeing introduced the Model 299, the prototype XB-17, during an impressive non-stop flight that covered 3,381 km (2,100 miles) from Seattle to Wright Field at Dayton, Ohio. The XB-17 easily beat two other bomber designs competing for a U. S. Army Air Corps production contract, but getting the Army General Staff to accept the arguments for long-range strategic bombers was difficult. By 1939, the Air Corps had accepted only 13 B-17s but that year, the situation changed dramatically after President Franklin Roosevelt began to legislate dramatic increases in weapons production. The number of Flying Fortresses in the Air Corps jumped to 200 by the time the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Yet, the airplane was hardly a 'Flying Fortress' when first introduced. Early B-17s such as the NASM B-17D lacked the advanced bombsights, defensive armament, armor, and self-sealing fuel tanks that appeared in later models. On April 28, 1941, Boeing delivered this particular B-17D (Army Air Corps serial number 40-3097) to the 19th Bombardment Group at March Field, California. On May 31, the group flew 21 Flying Fortresses to Hamilton Field near San Francisco. That evening, twenty airplanes from this group took off and flew 3,864 kilometers (2,400 miles) to Hickam Field, Hawaii. This was the first time that a mass, coordinated flight of land-based aircraft had flown to Hawaii. The Flying Fortresses departed Hamilton Field at five-minute intervals and landed at Hickam with less than six minutes between any two airplanes. For this flight, every crew member received the Distinguished Flying Cross.  Soon after 40-3097 arrived in Hawaii, Lieutenant Henry Godman joined the bomber's crew as pilot and aircraft commander. On September 5, the nine B-17Ds took off and continued flying west to reinforce the Philippine Islands. Godman flew 40-3097 as they followed the Pan American Clipper route and stopped to refuel at Midway Island, Wake Island, Port Moresby (New Guinea), and Batchelor Field, a Royal Australian Air Force base near Darwin, Australia. On September 12, the group landed at Clark Field, about 80.5 km (50 miles) northwest of Manila, ending the longest mass flight of land-based aircraft carried out to that time. On the night of December 5, a formation of Flying Fortresses that included the NASM aircraft flew 966 km (600 miles) to a partially completed landing strip at the Del Monte pineapple plantation on the island of Mindanao. Having successfully carried them halfway around the world, the crew had grown attached to this particular Flying Fortress and they named the bomber "Ole Betsy." They applied olive-drab camouflage paint over the original polished, natural-aluminum finish but they did not formalize the moniker with nose art. Months passed before the airplane acquired her permanent nickname "The Swoose" with distinctive half-goose, half-swan artwork.  A few hours after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor (7:55 am on December 7, 1941, but December 8 in the Philippines), "Ole Betsy" and another B-17 made reconnaissance flights around Mindanao--probably the first U. S. bomber missions of the war. In the weeks that followed, Godman flew the airplane on a number of missions from Del Monte to strike at Japanese forces invading the Philippines. Occasionally, the airplanes flew from Clark Field, although the Japanese had already destroyed much of the base. On December 18, "Ole Betsy" returned to Batchelor Field where the crew attempted to improvise protection against enemy fighters attacking from astern. These early Flying Fortresses had no tail gunner and the crew could not usually see enemy aircraft closing in from behind. "Ole Betsy" crewmen cut off the tailcone and rigged a .30-caliber machinegun to fire remotely when triggered by the waist gunner. Less than a week later, "Ole Betsy" took off to bomb Lingayen Gulf. Soon after taking off, Godman experienced engine trouble and elected to head for an alternate target at Davao Gulf instead of aborting. The airplane arrived over the Gulf in darkness. Using lights and movement in the harbor to aim, the bombardier released his bomb load. The lights scattered and the B-17 turned for home on the last leg of the first U. S. night bombing attack of World War II.  At the end of December, she relocated to a new base at Singosari, Java. During a mission to bomb Borneo's eastern coast on January 11, 1942, three enemy fighter aircraft mounted a 35-minute attack. The crew shot down two of the attackers and the B-17 escaped. The damage was extensive enough to end her career as a bomber. She was flown to Melbourne, Australia, for a complete overhaul and fitted with a new tail scavanged from another Flying Fortress (serial number 40-3091). Late in February, Captain Weldon Smith became the new pilot of this restored Flying Fortress. He christened the airplane "The Swoose" after a popular American song about a tormented gander: "Here comes little Alexander, what a funny looking gander. He's half swan and he's half goose, ha-ha-ha, he's just a Swoose." For an airplane pieced together from parts of other aircraft, Smith thought the name fit well. He flew the airplane for a short time, then moved on. On March 17, another pilot flew "The Swoose" back to Melbourne for extensive engine work. Mechanics may have removed the ventral "bathtub" machinegun compartment too. It had never worked well anyway and only added weight and drag. Captain Frank Kurtz selected it to ferry Lt. General George Brett, Commander of Allied Air Forces in Australia. "The Swoose" became the general's personal aircraft. It was in better condition than other B-17s at Melbourne and more complete with radios and armament. Brett flew "The Swoose" more than 150 hours per month across Australia and into the combat zone around Port Moresby. On one trip over Australia in June 1942, the crew became lost when navigation equipment malfunctioned and they force-landed near a sheep station outside Winton, Queensland. Among the passengers was Lt. Commander Lyndon B. Johnson on a fact-finding trip for President Roosevelt.  In May 1942 with Kurtz flying, the airplane broke the speed record flying from Sydney, Australia, to Wellington, New Zealand. In New Zealand, the crew removed all armament, lightening the bomber by hundreds of pounds, then broke another speed record during a flight to Honolulu. General Douglas MacArthur relieved Brett of his command in July. On August 4, 1942, Brett left Brisbane and returned home aboard the veteran B-17. Following a brief stop in Honolulu, he arrived at Hamilton Field, California, after flying for 36 hours and 10 minutes. Frank Kurtz had not just set another speed record, he brought home the first American combat bomber to return from the front. On November 9, Kurtz flew Brett in "The Swoose" to his new assignment at Albrook Field, Panama Canal Zone. Kurtz was so taken with the name, that he and his wife named their daughter Swoosie. Born September 6, 1944, Swoosie Kurtz became a stage, screen, and television actress. In July 1943, Frank Kurtz took command of the 463rd Bomb Group. The Army Air Corps also gave him a brand-new B-17G that he promptly named "The Swoose."  The B-17 that carried Brett across the Pacific remained as his personal aircraft but Capt. Jack Crane became the new pilot. Crane and "The Swoose" carried Brett to many countries in South America and the Caribbean but flying was about to halt temporarily. In February 1944 during a periodic inspection, the Panama Air Depot found numerous small cracks in the main spars of both wings between the landing gear and the fuselage. These flaws alone were not bad enough to ground the airplane permanently but the inspection also revealed severe corrosion in many areas. "The Swoose" was grounded and declared beyond economical repair. Fortunately, Crane was also an aeronautical engineer. Spurred by Brett's attachment to the old bomber, he tried to save it, because mechanics would cannibalize an airplane that could not fly for parts to maintain other aircraft. The biggest problems were the inboard wing panels. Mechanics had to replace these critical parts. While touring an abandoned parts depot, he found a pair of new panels earmarked for B-l7Bs. Crane had these parts installed, then proceeded to bring "The Swoose" up to the technical standards of the E-model B-17E. The upgrades included:

The lead crew stands in front of The Swoose after returning from a mission in Piombino, Italy, in April 1944. Shortly after the overhaul, mechanics also replaced the original B-17D segmented nose with a 2-piece B-17F assembly. The depot completely rejuvenated "The Swoose" in three months and she flew again on May 30, 1944. Brett continued to fly the bomber on trips around South America until late in 1945 when he returned to the United States aboard his adopted executive bomber on October 15. After several short trips around the country, the Army decommissioned the airplane at Kingman, Arizona, and General Brett retired. When Frank Kurtz heard plans to scrap the aircraft, he arranged for the City of Los Angeles to buy the old bomber for $350. The city planned to create a war memorial featuring the B-17. Mechanics hastily repainted the Flying Fortress in olive drab and black and returned it to flying condition. On April 6, 1946, Kurtz flew the airplane to Mines Field, the Los Angeles municipal airport. Among his passengers were the mayor of Los Angeles and Mrs. Kurtz. Following acceptance ceremonies, airport personnel stored the B-17 inside a hangar.  The city's plan for the war memorial fell through and hangar space became scarce and expensive. A new home was needed and once again, Frank Kurtz came to the rescue. He approached the Smithsonian and curator Paul Garber agreed to accept the bomber. In May 1948, Kurtz flew "The Swoose" to the old Douglas C-54 assembly plant at Park Ridge, Illinois. The building served the Smithsonian as temporary storage for a large number of museum aircraft. In June 1950, the Korean War began and the U. S. Air Force claimed the Park Ridge facility for military use. Smithsonian officials abandoned the hangar and on January 18, 1952, an Air Force crew flew "The Swoose" to Pyote, Texas. It was stored there, outdoors, wingtip to wingtip with the famous Boeing B-29 "Enola Gay."  Almost two years later, the Air Force agreed to move the bomber to Andrews AFB, Maryland, and store it there with other Smithsonian aircraft. On December 3, 1953, The Swoose began its last flight. This trip was not without incident and during the afternoon of the 5th, two engines quit. At dusk, a third engine failed just before touchdown at Andrews. For the next six years this historic aircraft was stored outdoors at the base and vandals almost picked the bomber clean. Finally, in April 1961, to save what remained of the airplane from total destruction, the Smithsonian disassembled and trucked the 60-year-old veteran to the National Air and Space Museum's Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility at Silver Hill, Maryland.

|

About that time Willie spotted a speck in the sky at 7 o'clock high. He hollered, "Shoot." It was an FW 190. The leading edge of the fighter's wing lit up as he fired his 20-mm cannon. Willie, Klug, Louie, and Fritz all shot at him. They thought they had gotten him, and this was later confirmed by some P-38 escorts. But he had also gotten us.

A 20-mm cannon shell had put a hole in one blade of the #2 engine, throwing it out of balance, so it had to be feathered. Another prop had a big nick out of it. Because of the flak and cannon damage, we had only two engines running. We were alone and more than 500 miles from our base. So we started to strip the plane of anything heavy. We threw out machine guns, ammunition, flak suits, armor plate, and even the bombsight. The latter was my addition and an action for which I was later reprimanded. The Norden bombsight was considered "secret," but the Germans must have had thousands of them from wrecked bombers. We were ready to drop the ball turret if necessary to make it back over the Balkan Mountains, but we didn't have to.

After we landed, we were congratulated on a job well done, and we congratulated each other. Silently, as we reflected on what we had just experienced, we wondered how many of us would finish 50 missions. For me, there were 42 more to go.

|

A flight of B-17s enroute to Hawaii on 7 December 1941 were assumed to be the large formation of aircraft tracked on radar early that Sunday morning. This formation turned out to be the carrier-based attack and fighter aircraft of Japan. The B-17s arrived later in the day and became the first B-17s to see combat in the Pacific Theater of Operations during WWII. |

||

| TYPE B-17D |

Number Built/Converted 42 |

Remarks Improved B-17C |

SPECIFICATIONS PERFORMANCE |

||

star.event.com

www.merriam-webster.com

www.sisterstv.com

www.rootsweb.com

www.kewpie.net

www.463rd.com

www.volny.cz

www.flipnrip.com

www.wpafb.af.mi

8thmn.org

Note: The "Swoose" is the oldest B-17 Flying Fortress in existence. It also the only known U.S. military airplane to have flown a combat mission on the first day of the US entry into World War II and to remain in continuous military flying service throughout the conflict.  The aircraft is in storage at the National Air and Space Museum’s Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility at Silver Hill, Maryland. Army's Most Decorated Pilot Col. Frank Kurtz, the most decorated Army Air Corps pilot in World War II, has died at age 85. He died Oct 31, 1996, at his home in Los Angeles of complications after a fall, his wife said.  He was an Olympic medalist diver and the most decorated Army Air Corps pilot in World War II, known for flying the last surviving B-17 Flying Fortress. Kurtz came from Missouri and, at the age of 14, hitchhiked to Los Angeles seeking top diving coaches. He developed as an athlete at Hollywood High School and USC. When Los Angeles hosted the Olympics in 1932, he competed in the high platform diving and won a bronze medal. Anticipating a career in commercial aviation, he joined the Army to train as a pilot.  1932 Olympic Games The three victors, for the United States in the high diving event is shown at the Olympics in Los Angeles. They are from left to right: Harold "Dutch" Smith, winner; Mickey Riley Galitzen, second; and Frank Kurtz, third. August 16, 1932 In the Philippines when the Japanese drew the U.S. into the war, Kurtz flew the last of the 35 planes stationed in the Pacific. When the plane was chewed up in combat, Kurtz and his crew dubbed it “part swan and part goose – the Swoose.” It has been called the most famous plane in the Pacific except for the Enola Gay, which carried the atom bomb dropped on Hiroshima. He then went to the European theater where he headed “the Swoose Group” and personally flew more than 60 missions over Italy and Germany. When Kurtz’s only child was born in Los Angeles during the war, news media immediately nicknamed her the second Swoose and the name stuck. She grew up to be the actress Swoosie Kurtz ’68. When he retired from the military, he became a top executive at the William May Garland development firm. Survivors include his wife and daughter.  Swoosie Kurtz Swoosie Kurtz is the only child of author Margo and Air Force Colonel Frank Kurtz. Due to her father's job she moved 17 times during school, lived in 8 different states. At the University of Southern California she majored in drama; later she attended the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, collected Broadway's "triple crown" (the Tony, Drama Desk and Outer Critics Circle awards) for her portrayal of Gwen in Lanford Wilson's "The Fifth of July". Since then she achieved much: has appeared in many TV shows and movies, got several Emmy and Golden Globe nominations and an Emmy for her guest-starring performance on Carol Burnett's comedy series "Carol & Company" (1990). She was quoted in the September 1984, Esquire on her name: "I'm named after 'The Swoose,' a B-15 bomber, which my father - Colonel Frank Kurtz, the most decorated pilot in World War II - flew." |

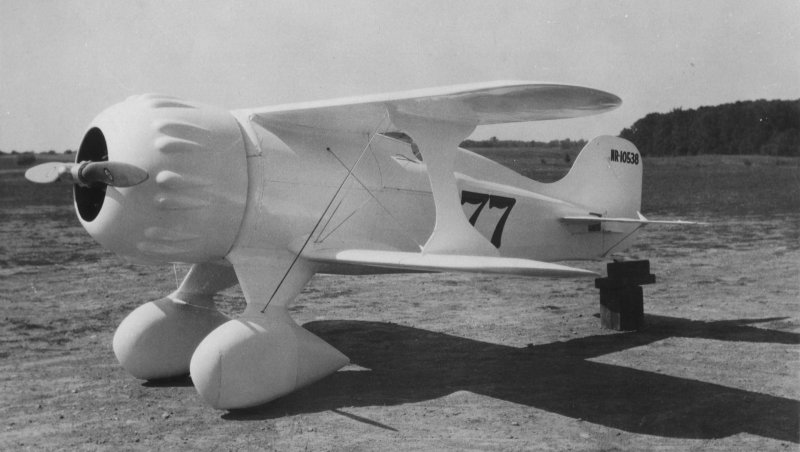

Laird "Super Solution"

Folks, be sure to update your anti-virus software. There's quite a few worms making the rounds.

Today's classic warship, USS Alabama (BB-60)

South Dakota class battleship

displacement. 35,000 tons

length. 680'

beam. 108'2"

draft. 36'2"

speed. 27.5 k.

complement. 1,793

armament. 9x16", 20x5"; 24x40 mm., 22x20 mm.

The USS Alabama (BB-60) was laid down on 1 February 1940 by the Norfolk (Va.) Navy Yard; launched on 16 February 1942; sponsored by Mrs. Lister Hill, wife of the senior Senator from Alabama; and commissioned on 16 August 1942, Capt. George B. Wilson in command.

After fitting out, Alabama commenced her shakedown cruise in Chesapeake Bay on Armistice Day (11 November) 1942. As the year 1943 began, the new battleship headed north to conduct operational training out of Casco Bay, Maine. She returned to Chesapeake Bay on 11 January 1943 to carry out the last week of shakedown training. Following a period of availability and logistics support at Norfolk, Alabama was assigned to Task Group (TG) 22.2, and returned to Casco Bay for tactical maneuvers on 13 February 1943.

With the movement of substantial British strength toward the Mediterranean theater, to prepare for the invasion of Sicily, the Royal Navy lacked the heavy ships necessary to cover the northern convoy routes. The British appeal for help on those lines soon led to the temporary assignment of Alabama and South Dakota (BB-57) to the Home Feet.

On 2 April 1943, Alabama as part of Task Force (TF) 22 sailed for the Orkney Islands with her sister ship and a screen of five destroyers. Proceeding via Little Placentia Sound, Argentia, Newfoundland, the battleship reached Scapa Flow on 19 May 1943, reporting for duty with TF 61 and becoming a unit of the British Home Fleet. She soon embarked on a period of intensive operational training to coordinate joint operations.

Early in June, Alabama and her sister ship, along with British Home Fleet units, covered the reinforcement of the garrison on the island of Spitzbergen, which lay on the northern flank of the convoy route to Russia, in an operation that took the ship across the Arctic Circle. Soon after her return to Scapa Flow, she was inspected by Admiral Harold R. Stark, Commander, United States Naval Forces, Europe.

Shortly thereafter, in July, Alabama participated in Operation "Governor," a diversion aimed toward southern Norway, to draw German attention away from the real Allied thrust, toward Sicily. It had also been devised to attempt to lure out the German battleship Tirpitz, the sister ship of the famed, but short-lived, Bismarck, but the Germans did not rise to the challenge, and the enemy battleship remained in her Norwegian lair.

Alabama was detached from the British Home Fleet on 1 August 1943, and, in company with South Dakota and screening destroyers, sailed for Norfolk, arriving there on 9 August. For the next ten days, Alabama underwent a period of overhaul and repairs. This work completed, the battleship departed Norfolk on 20 August 1943 for the Pacific. Transiting the Panama Canal five days later, she dropped anchor in Havannah Harbor, at Efate, in the New Hebrides, on 14 September.

Following a month and a half of exercises and training, with fast carrier task groups, the battleship moved to Fiji on 7 November. Alabama sailed on 11 November to take part in operation "Galvanic", the assault on the Japanese-held Gilbert Islands. She screened the fast carriers as they launched attacks on Jaluit and Mille atolls, Marshall Islands, to neutralize Japanese airfields located there. Alabama supported landings on Tarawa on 20 November and later took part in the securing of Betio and Makin. On the night of 26 November, Alabama twice opened fire to drive off enemy aircraft that approached her formation.

On 8 December 1943, Alabama, along with five other fast battleships, carried out the first Pacific gunfire strike conducted by that type of warship. Alabama's guns hurled 535 rounds into enemy strong points, as she and her sister ships bombarded Nauru Island, an enemy phosphate-producing center, causing severe damage to shore installations there. She also took the destroyer Boyd (DD-644), alongside after that ship had received a direct hit from a Japanese shore battery on Nauru, and brought three injured men on board for treatment.

She then escorted the carriers Bunker Hill (CV-17) and Monterey (CVL-26) back to Efate, arriving on 12 December. Alabama departed the New Hebrides for Pearl Harbor on 5 January 1944, arrived on the 12th, and underwent a brief drydocking at the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard. After replacement of her port outboard propeller, and routine maintenance, Alabama was again underway to return to action in the Pacific.

Alabama reached Funafuti, Ellice Islands, on 21 January 1944, and there rejoined the fleet. Assigned to Task Group (TG) 58.2, which was formed around Essex (CV-9), Alabama left the Ellice Islands on 25 January to help carry out Operation "Flintlock," the invasion of the Marshall Islands. Alabama, along with sister ship South Dakota and the fast battleship North Carolina (BB-55), bombarded Roi on 29 January and Namur on 30 January; she hurled 330 rounds of 16-inch and 1,562 of 5-inch toward Japanese targets, destroying planes, airfield facilities, blockhouses, buildings, and gun emplacements. Over the following days of the campaign, Alabama patrolled the area north of Kwajalein Atoll. On 12 February 1944, Alabama sortied with the Bunker Hill task group to launch attacks on Japanese installations, aircraft and shipping at Truk. Those raids, launched on 16 and 17 February, caused heavy damage to enemy shipping concentrated at that island base.

Leaving Truk Alabama began steaming toward the Marianas to assist in strikes on Tinian, Saipan and Guam. During this action, while repelling enemy air attacks on 21 February 1944, 5-inch mount no. 9 accidentally fired into mount no. 5. Five men died, and 11 were wounded in the mishap.

After the strikes were completed on 22 February, Alabama conducted a sweep looking for crippled enemy ships southeast of Saipan, and eventually returned to Majuro on 26 February 1944. There she served temporarily as flagship for Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher, Commander, TF 58, from 3 to 8 March.

Alabama's next mission was to screen the fast carriers as they hurled air strikes against Japanese positions on Palau, Yap, Ulithi, and Woleai, Caroline Islands. She steamed from Majuro on 22 March 1944 with TF 58 in the screen of Yorktown (CV-10), On the night of 29 March, about six enemy planes approached TG 58.3, in which Alabama was operating, and four broke off to attack ships in the vicinity of the battleship. Alabama downed one unassisted, and helped in the destruction of another.

On 30 March, planes from TF 58 began bombing Japanese airfields, shipping, fleet servicing facilities, and other installations on the islands of Palau, Yap, Ulithi and Woleai. During that day, Alabama again provided antiaircraft fire whenever e nemy planes appeared. At 2044 on the 30th, a single plane approached TG 58.3, but Alabama and other ships drove it off before it could cause any damage.

The battleship returned briefly to Majuro, before she sailed on 13 April with TF 58, this time in the screen of Enterprise (CV- 6). In the next three weeks, TF 58 hit enemy targets on Hollandia, Wakde, Sawar, and Sarmi along the New Guinea coast; covered Army landings at Aitape, Tanahmerah Bay, and Humboldt Bay; and conducted further strikes on Truk.

As part of the preliminaries to the invasion of the Marianas, Alabama, in company with five other fast battleships, shelled the large island of Ponape, in the Carolines, the site of a Japanese airfield and sea lane base. As Alabama's Capt. Fred T. Kirtland subsequently noted, the bombardment, of 70 minutes' duration, was conducted in a "leisurely manner." Alabama then returned to Majuro on 4 May 1944 to prepare for the invasion of the Marianas.

After a month spent in exercises and refitting, Alabama again got under way with TF 58 to participate in Operation "Forager." On 12 June, Alabama screened the carriers striking Saipan. On 13 June, Alabama took part in a six-hour preinvasion bombardment of the west coast of Saipan, to soften the defenses and cover the initial minesweeping operations. Her spotting planes reported that her salvoes had caused great destruction and fires in Garapan town. Though the shelling appeared successful, it proved a failure due to the lack of specialized training and experience required for successful shore bombardment. Strikes continued as troops invaded Saipan on 15 June.

On 19 June, during the Battle of the Philippine Sea, Alabama operated with TG 58.7, providing antiaircraft support for the fast carriers against attacking Japanese aircraft. The ships of TF 58 claimed 27 enemy planes downed during the course of the action which later came to be known as the "Marianas Turkey Shoot."

In the first raid that approached Alabama's formation, only two planes managed to penetrate to attack her sistership South Dakota, scoring one bomb hit that caused minor damage. An hour later a second wave, composed largely of torpedo bombers, bore in, but Alabama's barrage discouraged two planes from attacking South Dakota. The intense concentration paid to the incoming torpedo planes left one dive bomber nearly undetected, and it managed to drop its load near Alabama; the two small bombs were near-misses, and caused no damage.

American submarines sank two Japanese carriers and Navy pilots claimed a third carrier. American pilots and antiaircraft gunners had seriously depleted Japanese naval air power. Out of the 430 planes with which the enemy had commenced the Battle of the Philippine Sea, only 35 remained operational afterward.

Alabama continued patrolling areas around the Marianas to protect the American landing forces on Saipan, screening the east carriers as they struck enemy shipping, aircraft, and shore installations on Guam, Tinian, Rota, and Saipan. She then re tired to the Marshalls for upkeep.

Alabama-as flagship for Rear Admiral E. W. Hanson, Commander, Battleship Division 9-left Eniwetok on 14 July 1944, sailing with the task group formed around Bunker Hill. She screened the fast carriers as they conducted preinvasion attacks and support of the landings on the island of Guam on 21 July. She returned briefly to Eniwetok on 11 August. On 30 August she got underway in the screen of Essex to carry out Operation "Stalemate II" the seizure of Palau, Ulithi, and Yap. On 6 through 8 September, the forces launched strikes on the Carolinas.

Alabama departed the Carolines to sail to the Philippines and provided cover for the carriers striking the islands of Cebu, Leyte, Bohol and Negros from 12 to 14 September. The carriers launched strikes on shipping and installations in the Manila Bay area on 21 and 22 September, and in the central Philippines area on 24 September. Alabama retired briefly to Saipan on 28 September, then proceeded to Ulithi on 1 October 1944.

On 6 October 1944 Alabama sailed with TF 38 to support the liberation of the Philippines. Again operating as part of a fast carrier task group, Alabama protected the flattops while they launched strikes on Japanese facilities at Okinawa, in the Pescadores and Formosa.

Detached from the Formosa area on 14 October to sail toward Luzon, the fast battleship again used her antiaircraft batteries in support of the carriers as enemy aircraft attempted to attack the formation. Alabama's gunners claimed three enemy ai rcraft shot down and a fourth damaged. By 15 October, Alabama was supporting landing operations on Leyte. She then screened the carriers as they conducted air strikes on Cebu, Negros, Panay, northern Mindanao, and Leyte on 21 October 1944.

Alabama, as part of the Enterprise screen, supported air operations against the Japanese Southern Force in the area off Suriago Strait then moved north to strike the powerful Japanese Central Force heading for San Bernardino Strait. After receiving reports of a third Japanese force, the battleship served in the screen of the fast carrier task force as it sped to Cape Engano. On 24 October, although American air strikes destroyed four Japanese carriers in the Battle off Cape Engano, the Japanese Central Force under Admiral Kurita had transited San Bernardino Strait and emerged off the coast of Samar, where it fell upon a task group of American escort carriers and their destroyer and destroyer escort screen. Alabama reversed her course and headed for Samar to assist the greatly outnumbered American forces, but the Japanese had retreated by the time she reached the scene. She then joined the protective screen for the Essex task group to hit enemy forces in the central Philippines before retiring to Ulithi on 30 October 1944 for replenishment.

Underway again on 3 November 1944, Alabama screened the fast carriers as they carried out sustained strikes against Japanese airfields, and installations on Luzon to prepare for a landing on Mindoro Island. She spent the next few weeks engaged in operations against the Visayas and Luzon before retiring to Ulithi on 24 November.

The first half of December 1944 found Alabama engaged in various training exercises and maintenance routines. She left Ulithi on 10 December, and reached the launching point for air strikes on Luzon on 14 December, as the fast carrier task force s launched aircraft to carry out preliminary strikes on airfields on Luzon that could threaten the landings slated to take place on Mindoro. From 14 to 16 December, a veritable umbrella of carrier aircraft covered the Luzon fields, preventing any enemy planes from getting airborne to challenge the Mindoro-bound convoys. Having completed her mission, she left the area to refuel on 17 December; but, as she reached the fueling rendezvous, began encountering heavy weather. By daybreak on the 18th, rough seas and harrowing conditions rendered a fueling at sea impossible; 50 knot winds caused ships to roll heavily. Alabama experienced rolls of 30 degrees, had both her Vought "Kingfisher" float planes so badly damaged that they were of no further value, and received minor damage to her structure. At one point in the typhoon, Alabama recorded wind gusts up to 83 knots. Three destroyers, Hull (DD-350), Monaghan (DD-354), and Spence (DD- 512), were lost to the typhoon. By 19 December, the storm had run its course; and Alabama arrived back at Ulithi on 24 December. After pausing there briefly, Alabama continued on to Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, for overhaul.

The battleship entered drydock on 18 January 1945, and remained there until 25 February. Work continued until 17 March, when Alabama got underway for standardization trials and refresher training along the southern California coast. She got underway for Pearl Harbor on 4 April, arrived there on 10 April, and held a week of training exercises. She then continued on to Ulithi and moored there on 28 April 1945.

Alabama departed Ulithi with TF 58 on 9 May 1945, bound for the Ryukyus, to support forces which had landed on Okinawa on 1 April 1945, and to protect the fast carriers as they launched air strikes on installations in the Ryukyus and on Kyushu. On 14 May, several Japanese planes penetrated the combat air patrol to get at the carriers; one crashed Vice Admiral Mitscher's flagship. Alabama's guns splashed two, and assisted in splashing two more.

Subsequently, Alabama rode out a typhoon on 4 and 5 June, suffering only superficial damage while the nearby heavy cruiser Pittsburgh (CA-7O) lost her bow, Alabama subsequently bombarded the Japanese island of Minami Daito Shima, with other fast battleships, on 10 June 1945 and then headed for Leyte Gulf later in June to prepare to strike at the heart of Japan with the 3d Fleet.

On 1 July 1945, Alabama and other 3d Fleet units got underway for the Japanese home islands. Throughout the month of July 1945, Alabama carried out strikes on targets in industrial areas of Tokyo and other points on Honshu, Hokkaido, and Kyushu; on the night of 17 and 18 July, Alabama, and other fast battleships in the task group, carried out the first night bombardment of six major industrial plants in the Hitachi-Mito area of Honshu, about eight miles northeast of Tokyo. On board Alabama to observe the operation was retired Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd, the famed polar explorer.

On 9 August, Alabama transferred a medical party to the destroyer Ault (DD-698), for further transfer to the destroyer Borie (DD-704). The latter had been kamikazied on that date and required prompt medical aid on her distant picket station.

The end of the war found Alabama still at sea, operating off the southern coast of Honshu. On 15 August 1945, she received word of the Japanese capitulation. During the initial occupation of the Yokosuka-Tokyo area, Alabama transferred detachments of marines and bluejackets for temporary duty ashore; her bluejackets were among the first from the fleet to land. She also served in the screen of the carriers as they conducted reconnaissance flights to locate prisoner-of-war camps.

Alabama entered Tokyo Bay on 5 September to receive men who had served with the occupation forces, and then departed Japanese waters on 20 September. At Okinawa, she embarked 700 sailors, principally members of Navy construction battalions (or "Seabees") for her part in the Magic Carpet" operations. She reached San Francisco at mid-day on 15 October, and on Navy Day (27 October 1945) hosted 9,000 visitors. She then shifted to San Pedro, Calif., on 29 October. Alabama remained at San Pedro through 27 February 1946, when she left for the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard for inactivation overhaul. Alabama was decommissioned on 9 January 1947, at the Naval Station, Seattle, and was assigned to the Bremerton Group, United States Pacific Reserve Fleet. She remained there until struck from the Naval Vessel Register on 1 June 1962.

Citizens of the state of Alabama had formed the "USS Alabama Battleship Commission" to raise funds for the preservation of Alabama as a memorial to the men and women who served in World War II. The ship was awarded to that state on 16 June 1964, and was formally turned over on 7 July 1964 in ceremonies at Seattle. Alabama was then towed to her permanent berth at Mobile, Ala., arriving in Mobile Bay on 14 September 1964.

Alabama received nine battle stars for her World War II service.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.