Posted on 08/12/2025 2:13:14 PM PDT by ebb tide

Who can be an icon of Christ? The question haunts me. Documents of the Second Vatican Council teach that all good people who are part of the Church…all these good people relying on the exquisite promise of Christ’s resurrection are the Body of Christ. It would stand to reason, then that ‘all good people’ means precisely that. ‘All good people’ means all good men and…women.

Yet the Catholic Church has excised half its members from the fold. Cut free are all women. How? Women cannot be ordained to Church ministry, even though the clearest and most complete church histories include ordained women. What is the argument against ordaining women? The reduction of the complex reasoning is that women do not image Christ. Women cannot symbolize Christ. Women are not icons of Christ…It’s a scandal. It’s more than a scandal; it’s a disfigurement on the entire body of Christ by those who would deny both history and theology…that it is probably formally heretical.

The above indictment is from Women: Icons of Christ, authored by Phyllis Zagano. This well-respected scholar is arguably the leading advocate for the ordination of women to the diaconate, an issue to which she has devoted her theological career. She was a member of the 2016 Commission for the Study of the Diaconate of Women established by Pope Francis, which was reconvened in 2020. However, the final reports of both commissions have not been made public; and regarding the outcome of the 2016 commission, Francis commented during a 2019 in-flight press conference that “all had different positions, sometimes sharply different, they worked together and they agreed up to a point. Each one had his/her own vision, which was not in accord with that of the others, and the commission stopped there.” One can reasonably assume, due to its lack of publication, that the 2020 commission also failed to reach a consensus.

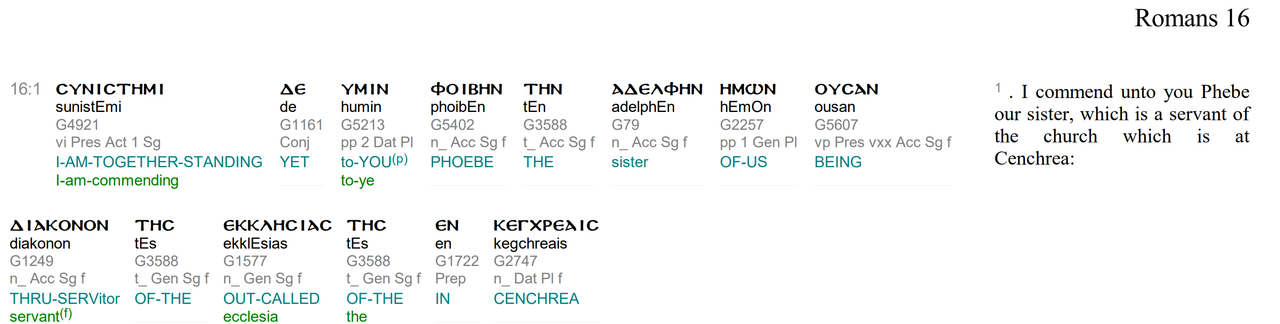

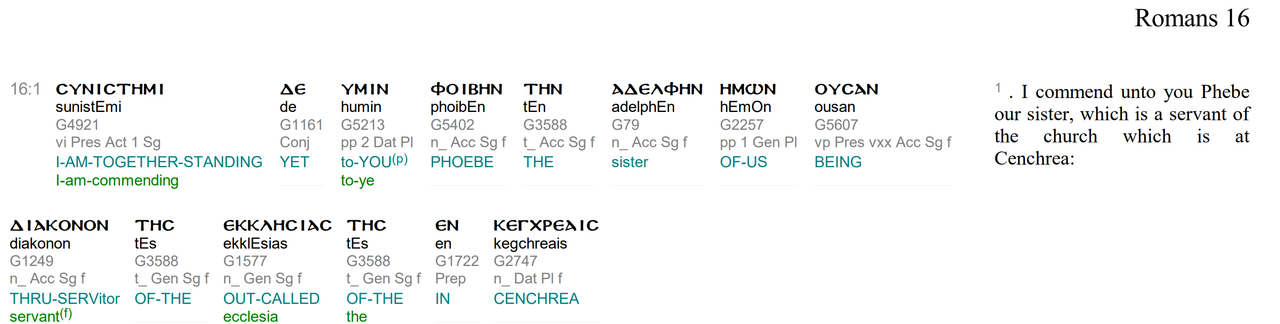

There are many in the Church who consider the ordination of women as deacons to be an unsettled question and are hopeful that perhaps newly-elected Pope Leo XIV will admit women to the diaconate. The fact is, during the early centuries of the Church women served as deaconesses—with the earliest reference found in St. Paul’s Letter to the Romans when he acknowledges the service of Phoebe “who is a deaconess of the Church of Cenchreae” (Romans 16:1). The question is what exactly was the function and ecclesial status of deaconesses in the early centuries of the Church. Under the pontificate of John Paul II, the International Theological Commission (ITC) produced an exhaustive study of the permanent diaconate, titled: From the Diakonia of Christ to the Diakonia of the Apostles—published in 2002.

The study provides a detailed examination of the history of the diaconate focused on New Testament evidence, the Apostolic Fathers, and early Church documents that include actual rites of ordination. According to this Commission, the three grades of the clergy—bishop, priest, and deacon—were already recognized by Pope Clement of Rome by the end of the first century. St. Ignatius of Antioch, who was martyred no later than 117, also acknowledged the three grades of the ecclesiastical hierarchy in his “Letter to the Trallians” (3, 1): “Let everyone revere the deacons as Jesus Christ, the bishop as the image of the Father, and the presbyters as the senate of God and the assembly of the Apostles. For without them one cannot speak of the Church.”

The three grades of the hierarchy, the “unicity of orders,” was also recognized by St. Cyprian, the third-century bishop of Carthage, when in Letter 15 he had to admonish deacons not to take the place of priests, as deacons “came in third in the order of the hierarchy.”1 This shows that the “unicity of orders”—in other words, the three grades of deacon, priest, and bishop—was not a late development and hardly a “modern accretion” as Zagano claims.2

It will not be possible in the space of this article to provide a full summary of early Church history on women deacons. If anyone wishes to delve more closely into the history of deaconesses in the Church, I recommend the monumental work of Aimé Georges Martimort, Deaconesses: An Historical Study. But what follows will at least give readers an understanding of the nature of the role of deaconesses in the Church’s early centuries. Outside of the New Testament, the Apostolic Tradition of St. Hippolytus, written no later than 220, contains instruction on the “installation” of widows—as widows were recognized as entering a kind of order within the assembly.

The Apostolic Tradition states that widows were “installed” and “not ordained” and there was no “laying on of hands because she does not offer the sacrifice [προθύματα] and she does not have a liturgical [ λειτουργία] function. Ordination [χειροτονία] is for clerics destined for liturgical service.”3 While this passage concerns the installation of widows, it serves as an indication that women set aside for ministry were not ordained because they were not clerics at the service of the altar. The Apostolic Tradition also verifies that male deacons were ordained by the imposition of hands by the bishop, meaning that the “unicity of orders” was also recognized in this third century document.

The institution of deaconesses was more prevalent in the Eastern Church than in the West. The Eastern Church document the Didascalia Apostolorum, dating from the first half of the third century, gives evidence of female deacons. The ultimate issue regarding the possibility of ordaining women to the diaconate, as Zagano rightly notes, has to do with whether women can sacramentally image Christ. To this point, it is interesting to note that the Didascalia teaches that while the bishop “is to be honored by you as God himself” it is the deacon “who stands in the place of Christ.” And as for deaconesses “they are to be honored by you as the Holy Spirit”—most probably because in Semitic languages spirit is a feminine noun.”4 In any case, according to this document, deaconesses did not represent Jesus.

The Didascalia provides detailed information on the exact duties of deaconesses, and it appears that they were needed to fulfill practical pastoral needs. Women ministered to other women as it was unseemly for men to do so. Deaconesses assisted in the baptismal ceremony of women who were indeed naked during the rite. Deaconesses anointed their bodies, as well as their heads. The deaconess would hold up a screen or drape to hide the body of the woman about to be baptized while the bishop, executing the baptismal rite, extended his hand over the drape to avoid seeing the woman.

It is important to note that deaconesses could not perform the actual sacrament of baptism. According to the Didascalia, this could only be done by a bishop, priest, or male deacon.5 After the baptism, deaconesses continued to instruct the women, nurturing them in the Faith. Indeed, for the sake of modesty and to avoid scandal, only women could instruct other women, and this ministry was conducted by female deacons.

An Eastern Church fifth-century document called The Testament of Our Lord Jesus Christ reveals the duties of widows as well as deaconesses. Indeed, widows actually performed many of the tasks associated with deaconesses—assisting in the baptism of women and instructing women. Oddly, in this document, the ministry of widows took precedence over that of deaconesses “occupying a very humble place in the scheme of things.”6

Were women actually ordained as deacons? The rite of installation of widows according to the Apostolic Tradition of St. Hippolytus states: “The ordination…of widows is to be carried out in the following manner….” However, he is very clear that this “ordination” did not employ “laying on of hands.” And The Testament, following Hippolytus, indicates that the laying on of hands was restricted to the three sacerdotal orders.7

According to another fifth-century document—The Ordo and Canons Concerning Ordination in the Holy Church—the bishop laid his hand on the woman about to become a deaconess—but for the purposes of praying for her. The document states that this prayer “in no way resembles the prayer used in the ordination of a deacon. The deaconess should not approach the altar; her task lies principally in assisting with the anointing at baptisms.”8 There are occasions when the Greek terms “installation” and “ordination” were used interchangeably when it came to the ceremonies for widows and deaconesses.

According to the Apostolic Constitutions, a text dependent on the Didascalia, dated between 375 and 380, deaconesses were forbidden to teach even other women, nor could they conduct baptisms, as could male deacons.9

The Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches:

Holy Orders is the sacrament through which the mission entrusted by Christ to his apostles continues to be exercised in the Church until the end of time: thus it is the sacrament of apostolic ministry. It includes three degrees: episcopate, presbyterate, and diaconate. (1536)

Article 1538 states: “Today the word ‘ordination’ is reserved for the sacramental act which integrates a man (vir) into the order of bishops, presbyters, or deacons.” Article 1577 is especially significant. Here we see, quoting Canon 1014 directly, that

“Only a baptized man (vir) validly receives sacred ordination.” The Lord Jesus chose men (viri) to form the college of the twelve apostles, and the apostles did the same when they chose collaborators to succeed them in their ministry. The college of bishops, with whom the priests are united in the priesthood, makes the college of the twelve an ever-present and ever-active reality until Christ’s return. The Church recognizes herself to be bound by this choice made by the Lord himself. For this reason, the ordination of women is not possible.

It can safely be said that at this point in the development of the Church’s doctrine regarding the role and ministry of deacons, women are excluded from participating in Holy Orders. What must be realized is that the reservation of Holy Orders to males is ontologically ordered, meaning that there is an objective relation between what it means to be male and the reception of an “indelible spiritual character” that causes those receiving ordination to sacramentally image Christ.

Zagano argues, however, that men and women equally image Jesus, thus women certainly can be, by ordination, sacramentally configured “in persona Christi servi, in the person of Christ the servant” the ministry to which deacons are ordained.10 Zagano realizes that for her position to prevail she must prove how women sacramentally image Christ. She states:

The question is not one of functionality. The question is one of the Church proclaiming the Gospel in a new-old way. Beneath every objection to restoring women to the ordained diaconate is the suggestion that women cannot image Christ. Of course women do not image the human male Jesus exactly. But the extraordinary fact of the Incarnation is Jesus, God, became human. Women are human. And all humans are made in the image and likeness of God. The andocentric blind spot in the theologies denying the ability of women to image Christ belie a naïve physicalism embedded in arguments against the ordination of women to any grade of order including the diaconate.11

Zagano’s argument on how women are icons of Christ is shallow and simplistic. Indeed, as will be demonstrated, it is precisely because women do not, and cannot, “image the human male Jesus” that they cannot be admitted to Holy Orders. For her, all that’s required is that a person—whether male or female—be baptized to be eligible to receive the sacrament of Holy Orders. That’s it. This is because, for Zagano, human sexuality essentially has no sacramental meaning. This position is reflected in her statement that: “In fact the humanity of Christ overcomes the limitations of gender and no church document argues an ontological distinction among humans except documents that address the question of ordination.”12

If ontological equality is all that is needed for women to be ordained, no real reason exists to bar women from the ministerial priesthood. In her 2003 America magazine article, Zagano stated: “I am not arguing for women priests.”13 However, based on her argument that both baptized men and women image Jesus equally, she did argue for women’s ordination to the priesthood and diaconate in her 2011 book, Women & Catholicism: Gender, Communion, and Authority. This was well after St. John Paul II, in 1994, closed the door on the issue of women’s admission to the priesthood. In his apostolic letter Ordinatio Sacerdotalis, he infallibly proclaimed that the all-male priesthood pertained “to the Church’s divine constitution itself” and that “the Church has no authority whatsoever to confer priestly ordination on women and that this judgment is to be definitively held by all the Church’s faithful.”

In order to get women capable of receiving Holy Orders, Zagano’s flat theology of image completely ignores the very nature of the covenant of redemption—a covenant that is nuptially ordered according to the very way God in Christ is in union with His people. Yes, in terms of what it means to be human, made in the image of God, men and women on that level are ontologically equal. But according to the nuptially ordered covenant, males and females are indeed differentiated according to the sacramental meaning of their gender.

Women do not, and cannot, “image the human male Jesus” because according to the nuptial order of the covenant this is not the meaning of female sexuality. The world is saved by the marriage between Christ and the Church. This is not simply a nice way of talking. This is a supernatural, God-ordained reality made sacramentally present in the human sexuality of men and women. The teaching of St. Paul confirms this truth.

Husbands love your wives as Christ loved the church. He gave himself up for her to make her holy, purifying her in the bath of water by the power of the word, to present to himself a glorious church without stain or wrinkle or anything of that sort. Husbands should love their wives as they do their own bodies. He who loves his wife loves himself. Observe that no one ever hates his own flesh; no he nourishes it and cares for it as Christ cares for the church—for we are members of his body. “For this reason a man shall leave his father and his mother, and shall cling to his wife, and the two shall become one flesh.” This is a great mystery; I mean that it refers to Christ and the Church. (Ephesians 5:25-32)

This is remarkable. What has Paul just stated? Namely, that from the Beginning male and female sexuality was intended by God to be transcendent, a sacramental sign—a sacramental sign of the covenant of redemption maritally ordered. This means that males and females are given sexual redemptive roles—that male and female gender is not just functional biology slapped over the sexless soul. Zagano certainly tends toward this dualist anthropology when she states that the Church must accept the sacramental ordination of women because “the soul enfleshed as female can receive the grace and charism of orders.”14

The Marital Order of the Covenant

That the covenant of redemption is maritally ordered was confirmed by the Vatican’s 1976 Declaration Inter Insigniores, issued under the authority of St. Pope Paul VI. The document explains why women cannot be admitted to the ministerial priesthood. It provides essentially five reasons. The fifth reason refers to the nuptial character of the covenant:

For the salvation offered by God to men and women, the union with him to which they are called—in short, the Covenant—took on, from the Old Testament Prophets onwards, the privileged form of a nuptial mystery: for God the Chosen People is seen as his ardently loved spouse. Both Jewish and Christian tradition has discovered the depth of this intimacy of love by reading and rereading the Song of Songs; the divine Bridegroom will remain faithful even when the Bride betrays his love, when Israel is unfaithful to God (Hos.1-3; Jer.2).

And this document makes an almost shocking affirmation: “For Christ himself was and remains a man (vir).” In other words, even now Christ in glory has not shed his male gender, it is forever an essential part of His personal identity—namely, that He as Savior is forever bridegroom to the Church which is His bride. Christ taking on male sexuality is not accidental or random—rather, Christ’s male gender has salvific value.

The marital relationship between Christ and His Church was ratified once and for all with His sacrificial death upon the Cross—when He “gave himself up for her.” Christ’s death forms the New Covenant, and it is this very covenant that is made present in the sacrifice of the Mass. The priest, in persona Christi, pronounces the very words that signify this covenant: “This is my Body given up, this is my Blood shed for you.” In the sacrifice of Christ, it is the man who gives up His life for the woman. This means—and this is the issue we must take most seriously if we are to understand why women cannot be admitted to Holy Orders—women, far from being, as Zagano claims, “excised,” far from being second-class members of the Body of Christ, women are the Church in relation to Christ her Head.

St. Edith Stein, the great German philosopher and martyr, who wrote extensively on the role of women in society and in the Church, stated: “Woman…is called upon to embody in her highest and purest development the essence of the Church—to be its symbol.”15 If men in Holy Orders image Christ to His people—the sacramental nature of male gender is in relation as Christ the male Savior is in relation to what is feminine—namely, the people of God. Note that the Church is called the Bride of Christ and, going all the way back to the Fathers of the Church, she is called mater ecclesia—mother Church—birthing new children of God in the womb of the baptismal font as St. Cyprian said so famously in On the Unity of the Catholic Church: “You cannot have God for your Father, if you do not have the Church for your Mother.”

Keeping in mind that the Eucharist is the nuptially ordered sacrifice of Christ offered by those who by ordination stand in persona Christi Capitas—the sacrifice of the Bridegroom for His Bride—the question is how then are deacons icons of Christ on the side of Christ the Bridegroom? Lumen Gentium, when reestablishing the permanent diaconate, teaches:

At a lower level of the hierarchy are deacons, upon whom hands are imposed “not unto the priesthood, but unto a ministry of service.” For strengthened by sacramental grace, in communion with the bishop and his group of priests they serve in the diaconate of the liturgy, of the word, and of charity to the people of God. (LG 29)16

Here we see that the diaconate is part of the sacrament of Holy Orders, and deacons are placed within the hierarchy. The Church’s hierarchy composed of bishops, priests, and deacons all image Christ to the Church. This is actually an important point, as I have deliberately emphasized the word “to” because the hierarchy is in relation to the Church as Bride. Deacons are in communion with the bishop and his group of priests to the Church. The Didascalia describes the role of the deacon:

For we are imitators of Him, and hold the place of Christ. And again in the Gospel you find it written how our Lord girded a linen cloth about his loins and cast water into a wash-basin, while we reclined (at supper), and drew nigh and washed the feet of us all and wiped them with the cloth [Jn. 13.4-5].? Now this He did that He might show us (an example of) charity and brotherly love, that we also should do in like manner one to another [cf. Jn. 13.14-15]. If then our Lord did thus, will you, O deacons, hesitate to do the like for them that are sick and infirm, you who are workmen of the truth, and bear the likeness of Christ?17

Whether or not a deacon is configured by ordination in persona Christi Capitas—it is clear that his service of ministry is not separate from the person of Christ the priest—but intimately associated with the service Christ the Bridegroom offers to His people. One may say that the “unicity of orders” is tied to the unicity of the person of Christ. Christ the priest and Christ the servant are united in who Christ is to His people. If this is true, ordaining women to the diaconate creates sacramental incoherency—as we have demonstrated that the Covenant of Redemption is maritally ordered. Women are on the side of the Church to Christ—not on the side of Christ the male Bridegroom to His Church.

Commenting on the distinction between a layman’s service and the sacramental nature of the deacon, the ITC document states:

[T]he deciding factor would be what the deacon was rather than what he did: the action of the deacon would bring about a special presence of Christ the Head and Servant that was proper to sacramental grace, configuration with Him…The viewpoint of faith and the sacramental reality of the diaconate would enable its particular distinctiveness to be discovered and affirmed, not in relation to its functions but in relation to its theological nature and its representative symbolism.

The most common mistake nearly all feminist theologians make is that women will never be equal to men unless they stand in the sanctuary alongside priests, as if the sanctuary was the great equalizer. But as shown here, the dignity of women is already secured in their being the sign of the Bridal Church to Christ. And frankly, as never before, all sorts of ministries are open to women, who in various capacities exercise tremendous authority in the Church, some even occupying the position of diocesan chancellor and heading certain Vatican departments, as Sr. Simona Brambilla heads up the Vatican’s Dicastery for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life.

Could, however, the Church reinstitute deaconesses? The answer is yes, but this would be an installation to a recognized formal office consecrating women to service completely separate from male ordination to the diaconate within the sacrament of Holy Orders. But considering the many paths of ministry now open to women, is there even such a need for feminine formal office? In any case, as Canon 1024 states: “A baptized male alone receives sacred ordination validly.”

Ping

Jesus of Nazareth was a man, the son of Mary: a male human. (He is a divine PERSON with both male human nature an divine nature.)

A person with female human nature CANNOT, therefore, be an icon of HIM.

If I understood this women cannot be deacons because women cannot be deacons.

Apparently you didn’t even bother to read the article.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.