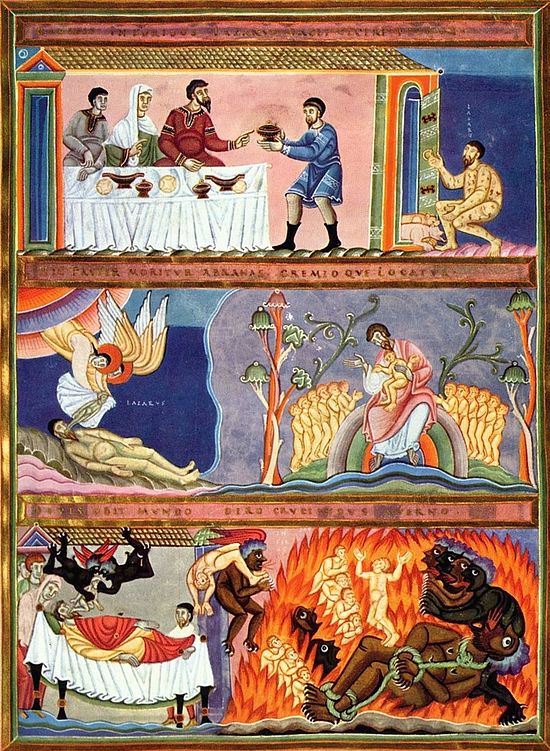

Luke CHAP. 16

16:19–2119. There was a certain rich man, which was clothed in purple and fine linen, and fared sumptuously every day:

20. And there was a certain beggar named Lazarus, which was laid at his gate, full of sores,

21. And desiring to be fed with the crumbs which fell from the rich man’s table: moreover the dogs came and licked his sores.

BEDE. Our Lord had just before advised the making friends of the Mammon of unrighteousness, which the Pharisees derided. He next confirms by examples what he had set before them, saying, There was a certain rich man, &c.

CHRYSOSTOM. There was, not is, because he had passed away as a fleeting shadow.

AMBROSE. But not all poverty is holy, or all riches criminal, but as luxury disgraces riches, so does holiness commend poverty.

It follows, And he was clothed in purple and fine linen.

BEDE. (bysso.) Purple, the colour of the royal robe, is obtained from sea shells, which are scraped with a knife. Byssus is a kind of white and very fine linen.

GREGORY. (Hom. 40. in Ev.) Now if the wearing of fine and precious robes were not a fault, the word of God would never have so carefully expressed this. For no one seeks costly garments except for vainglory, that he may seem more honourable than others; for no one wishes to be clothed with such, where he cannot be seen by others.

CHRYSOSTOM. (ut sup.) Ashes, dust, and earth he covered with purple, and silk; or ashes, dust, and earth bore upon them purple and silk. As his garments were, so was also his food. Therefore with us also as our food is, such let our clothing be Hence it follows, And he fared sumptuously every day.

GREGORY. (Hom. 40. in Ev.) And here we must narrowly watch ourselves, seeing that banquets can scarcely be celebrated blamelessly, for almost always luxury accompanies feasting; and when the body is swallowed up in the delight of refreshing itself, the heart relaxes to empty joys.

It follows, And there was a certain beggar named Lazarus.

AMBROSE. This seems rather a narrative than a parable, since the name is also expressed.

CHRYSOSTOM. (ut sup.) But a parable is that in which an example is given, while the names are omitted. Lazarus is interpreted, “one who was assisted.” For he was poor, and the Lord helped him.

CYRIL OF ALEXANDRIA. Or else; This discourse concerning the rich man and Lazarus was written after the manner of a comparison in a parable, to declare that they who abound in earthly riches, unless they will relieve the necessities of the poor, shall meet with a heavy condemnation. But the tradition of the Jews relates that there was at that time in Jerusalem a certain Lazarus who was afflicted with extreme poverty and sickness, whom our Lord remembering, introduces him into the example for the sake of adding greater point to His words.

GREGORY. (Moral. 1. c. 8.) We must observe also, that among the heathen the names of poor men are more likely to be known than of rich. Now our Lord mentions the name of the poor, but not the name of the rich, because God knows and approves the humble, but not the proud. But that the poor man might be more approved, poverty and sickness were at the same time consuming him; as it follows, who was laid at his gale full of sores.

PSEUDO-CHRYSOSTOM. (Hom. de Div.) He lay at his gate for this reason, that the rich might not say, I never saw him, no one told me; for he saw him both going out and returning. The poor is full of sores, that so he might set forth in his own body the cruelty of the rich. Thou seest the death of thy body lying before the gate, and thou pitiest not. If thou regardest not the commands of God, at least have compassion on thy own state, and fear lest also thou become such as he. But sickness has some comfort if it receives help. How great then was the punishment in that body, in which with such wounds he remembered not the pain of his sores, but only his hunger; for it follows, desiring to be fed with the crumbs, &c. As if he said, What thou throwest away from thy table, afford for alms, make thy losses gain.

AMBROSE. But the insolence and pride of the wealthy is manifested afterwards by the clearest tokens, for it follows, and no one gave to him. For so unmindful are they of the condition of mankind, that as if placed above nature they derive from the wretchedness of the poor an incitement to their own pleasure, they laugh at the destitute, they mock the needy, and rob those whom they ought to pity.

AUGUSTINE. (Serm. 367.) For the covetousness of the rich is insatiable, it neither fears God nor regards man, spares not a father, keeps not its fealty to a friend, oppresses the widow, attacks the property of a ward.

GREGORY. (in Ev. Hom. 40.) Moreover the poor man saw the rich as he went forth surrounded by flatterers, while he himself lay in sickness and want, visited by no one. For that no one came to visit him, the dogs witness, who fearlessly licked his sores, for it follows, moreover the dogs came and licked his sores.

PSEUDO-CHRYSOSTOM. (ut sup.) Those sores which no man deigned to wash and dress, the beasts tenderly lick.

GREGORY. (ubi sup.) By one thing Almighty God displayed two judgments. He permitted Lazarus to lie before the rich man’s gate, both that the wicked rich man might increase the vengeance of his condemnation, and the poor man by his trials enhance his reward; the one saw daily him on whom he should shew mercy, the other that for which he might be approved.

16:22–26

22. And it came to pass, that the beggar died, and was carried by the angels into Abraham’s bosom: the rich man also died, and was buried;

23. And in hell he lift up his eyes, being in torments, and seeth Abraham afar off, and Lazarus in his bosom.

24. And he cried and said, Father Abraham, have mercy on me, and send Lazarus, that he may dip the tip of his finger in water, and cool my tongue; for I am tormented in this flame.

25. But Abraham said, Son, remember that thou in thy lifetime receivedst thy good things, and likewise Lazarus evil things: but now he is comforted, and thou art tormented.

26. And beside all this, between us and you there is a great gulf fixed: so that they which would pass from hence to you cannot; neither can they pass to us, that would come from thence.

PSEUDO-CHRYSOSTOM. (ubi sup.) We have heard how both fared on earth, let us see what their condition is among the dead. That which was temporal has passed away; that which follows is eternal. Both died; the one angels receive, the other torments; for it is said, And it came to pass, that the beggar died, and was carried by the angels, &c. Those great sufferings are suddenly exchanged for bliss. He is carried after all his labours, because he had fainted, or at least that he might not tire by walking; and he was earned by angels. One angel was not sufficient to carry the poor man, but many come, that they may make a joyful band, each angel rejoicing to touch so great a burden. Gladly do they thus encumber themselves, that so they may bring men to the kingdom of heaven. But he was carried into Abraham’s bosom, that he might be embraced and cherished by him; Abraham’s bosom is Paradise. And the ministering angels carried the poor man, and placed him in Abraham’s bosom, because though he lay despised, he yet despaired not nor blasphemed, saying, This rich man living in wickedness is happy and suffers no tribulation, but I cannot get even food to supply my wants.

AUGUSTINE. (de Orig. Anim. 4. 16) Now as to your thinking Abraham’s bosom to be any thing bodily, I am afraid lest you should be thought to treat so weighty a matter rather lightly than seriously. For you could never be guilty of such folly, as to suppose the corporeal bosom of one man able to hold so many souls, nay, to use your own words, so many bodies as the Angels carry thither as they did Lazarus. But perhaps you imagine that one soul to have alone deserved to come to that bosom. If you would not fall into a childish mistake, you must understand Abraham’s bosom to be a retired and hidden resting-place where Abraham is; and therefore called Abraham’s, not that it is his alone, but because he is the father of many nations, and placed first, that others might imitate his preeminence of faith.

GREGORY. (in Hom. 40.) When the two men were below on earth, that is, the poor and the rich, there was one above who saw into their hearts, and by trials exercised the poor man to glory, by endurance awaited the rich man to punishment. Hence it follows, The rich man also died.

CHRYSOSTOM. (Hom. 6. in 2 ad Cor.) He died then indeed in body, but his soul was dead before. For he did none of the works of the soul. All that warmth which issues from the love of our neighbour had fled, and he was more dead than his body. (Conc. 2. de Lazaro.). But no one is spoken of as having ministered to the rich man’s burial as to that of Lazarus. Because when he lived pleasantly in the broad road, he had many busy flatterers; when he came to his end, all forsook him. For it simply follows, and was buried in hell. But his soul also when living was buried, enshrined in its body as it were in a tomb.

AUGUSTINE. The burial in hell is the lowest depth of torment which after this life devours the proud and unmerciful.

PSEUDO-BASIL. (In Esai. 5.) Hell is a certain common place in the interior of the earth, shaded on all sides and dark, in which there is a kind of opening stretching downward, through which lies the descent of the souls who are condemned to perdition.

PSEUDO-CHRYSOSTOM. (Chrys. Op. imp, Hom. 53. Matt. 8:22, 25.) Or as the prisons of kings are placed at a distance without, so also hell is somewhere far off without the world, and hence it is called the outer darkness.

THEOPHYLACT. But some say that hell is the passing from the visible to the invisible, and the unfashioning of the soul. For as long as the soul of the sinner is in the body, it is visible by means of its own operations. But when it flies out of the body, it becomes shapeless.

CHRYSOSTOM. (Conc. 2. de Lazaro.) As it made the poor man’s affliction heavier while he lived to lie before the rich man’s gate, and to behold the prosperity of others, so when the rich man was dead it added to his desolation, that he lay in hell and saw the happiness of Lazarus, feeling not only by the nature of His own torments, but also by the comparison of Lazarus’s honour, his own punishment the more intolerable. Hence it follows, But lifting up his eyes, He lifted up his eyes that he might look on him, not despise him; for Lazarus was above, he below. Many angels earned Lazarus; he was seized by endless torments. Therefore it is not said, being in torment, but torments. For he was wholly in torments, his eyes alone were free, so that he might behold the joy of another. His eyes are allowed to be free that he may be the more tortured, not having that which another has. The riches of others are the torments of those who are in poverty.

GREGORY. (lib. 4. Mor. c. 29.) Now if Abraham sate below, the rich man placed in torments would not see him. For they who have followed the path to the heavenly country, when they leave the flesh, are kept back by the gates of hell; not that punishment smites them as sinners, but that resting in some more remote places, (for the intercession of the Mediator was not yet come,) the guilt of their first fault prevents them from entering the kingdom.

CHRYSOSTOM. (ad Hom. 2. in ep. Phil. Chrys. Conc. de Laz.) There were many poor righteous men, but he who lay at his door met his sight to add to his woe. For it follows, And Lazarus in his bosom. It may here be observed, that all who are offended by us are exposed to our view. But the rich man sees Lazarus not with any other righteous man, but in Abraham’s bosom. For Abraham was full of love, but the man is convicted of cruelty. Abraham sitting before his door followed after those that passed by, and brought them into his house, the other turned away even them that abode within his gate.

GREGORY. (Hom. 40. in Ev.) And this rich man forsooth, now fixed in his doom, seeks as his patron him to whom in this life he would not shew mercy.

THEOPHYLACT. He does not however direct his words to Lazarus, but to Abraham, because he was perhaps ashamed, and thought Lazarus would remember his injuries; but he judged of him from himself. Hence it follows, And he cried and said.

PSEUDO-CHRYSOSTOM. (Hom. de Div.) Great punishments give forth a great cry. Father Abraham. As if he said, I call thee father by nature, as the son who wasted his living, although by my own fault I have lost thee as a father. Have mercy on me. In vain thou workest repentance, when there is no place for repentance; thy torments drive thee to act the penitent, not the desires of thy soul. He who is in the kingdom of heaven, I know not whether he can have compassion on him who is in hell. The Creator pitieth His creature. There came one Physician who was to heal all; others could not heal. Send Lazarus. Thou errest, wretched man. Abraham cannot send, but he can receive. To dip the tip of his finger in water. Thou wouldest not deign to look upon Lazarus, and now thou desirest his finger. What thou seekest now, thou oughtest to have done to him when alive. Thou art in want of water, who before despisedst delicate food. Mark the conscience of the sinner; he durst not ask for the whole of the finger. We are instructed also how good a thing it is not to trust in riches. (Chrys. Conc. 2. de Laz). See the rich man in need of the poor who was before starving. Things are changed, and it is now made known to all who was rich and who was poor. For as in the theatres, when it grows towards evening, and the spectators depart, then going out, and laying aside their dresses, they who seemed kings and generals are seen as they really are, the sons of gardeners and fig-sellers. So also when death is come, and the spectacle is over, and all the masks of poverty and riches are put off, by their works alone are men judged, which are truly rich, which poor, which are worthy of honour, which of dishonour.

GREGORY. (ut sup.) For that rich man who would not give to the poor man even the scraps of his table, being in hell came to beg for even the least thing. For he sought for a drop of water, who refused to give a crumb of bread.

BASIL. But he receives a meet reward, fire and the torments of hell; the parched tongue; for the tuneful lyre, wailing; for drink, the intense longing for a drop; for curious or wanton spectacles, profound darkness; for busy flattery, the undying worm. Hence it follows, That he may cool my tongue, for I am tormented in the flame.

CHRYSOSTOM. (ubi sup.) But not because he was rich was he tormented, but because he was not merciful.

GREGORY. We may gather from this, with what torments he will be punished who robs another, if he is smitten with the condemnation to hell, who does not distribute what is his own.

AMBROSE. He is tormented also because to the luxurious man it is a punishment to be without his pleasures; water is also a refreshment to the soul which is set fast in sorrow.

GREGORY. But what means it, that when in torments he desires his tongue to be cooled, except that at his feasts having sinned in talking, now by the justice of retribution, his tongue was in fierce flame; for talkativeness is generally rife at the banquet.

CHRYSOSTOM. His tongue too had spoken many proud things. Where the sin is, there is the punishment; and because the tongue offended much, it is the more tormented.

CHRYSOSTOM. Or, in that he wishes his tongue to be cooled, when he was altogether burning in the flame, that is signified which is written, Death and life are in the hands of the tongue, (Prov. 18:21.) and with the mouth confession is made to salvation; (Rom. 10:10.) which from pride he did not do, but the tip of the finger means the very least work in which a man is assisted by the Holy Spirit.

AUGUSTINE. (de Orig. Anim. 4. 16.) Thou sayest that the members of the soul are here described, and by the eye thou wouldest have the whole head understood, because he was said to lift up his eyes; by the tongue, the jaws; by the finger, the hand. But what is the reason that those names of members when spoken of God do not to thy mind imply a body, but when of the soul they do? It is that when spoken of the creature they are to be taken literally, but when of the Creator metaphorically and figuratively. Wilt thou then give us bodily wings, seeing that not the Creator, but man, that is, the creature, says, If I take not the wings in the morning? (Ps. 139:9.) Besides, if the rich man had a bodily tongue, because he said, to cool my tongue, in us also who live in the flesh, the tongue itself has bodily hands, for it is written, Death and life are in the hands of the tongue. (Prov. 18:21.)

GREGORY OF NYSSA. (Orat. 5. de Beat.) As the most excellent of mirrors represents an image of the face, just such as the face itself which is opposite to it, a joyful image of that which is joyful, a sorrowful of that which is sorrowful; so also is the just judgment of God adapted to our dispositions. Wherefore the rich man because he pitied not the poor as he lay at his gate, when he needs mercy for himself, is not heard, for it follows, And Abraham said unto him, Son, &c.

CHRYSOSTOM. (Conc. 2, 3. de Lazaro.) Behold the kindness of the Patriarch; he calls him son, (which may express his tenderness,) yet gives no aid to him who had deprived himself of cure. Therefore he says, Remember, that is, consider the past, forget not that thou delightedst in thy riches, and thou receivedst good things in thy life, that is, such as thou thoughtest to be good. Thou couldest not both have triumphed on earth, and triumph here. Riches can not be true both on earth and below. It follows, And Lazarus likewise evil things; not that Lazarus thought them evil, but he spoke this according to the opinion of the rich man, who thought poverty, and hunger, and severe sickness, evils. When the heaviness of sickness harasses us, let us think of Lazarus, and joyfully accept evil things in this life.

AUGUSTINE. (Quæst. Ev. Lib. ii. qu. 38.) All this then is said to Him because he chose the happiness of the world, and loved no other life but that in which he proudly boasted; but he says, Lazarus received evil things, because he knew that the perishableness of this life, its labours, sorrows, and sickness, are the penalty of sin, for we all die in Adam who by transgression was made liable to death.

CHRYSOSTOM. (Conc. 3. de Lazaro.) He says, Thou receivedst good things in thy life, (as if thy due;) as though he said, If thou hast done any good thing for which a reward might be due, thou hast received all things in that world, living luxuriously, abounding in riches, enjoying the pleasure of prosperous undertakings; but he if he committed any evil has received all, afflicted with poverty, hunger, and the depths of wretchedness. And each of you came hither naked; Lazarus indeed of sin, wherefore he receives his consolation; thou of righteousness, wherefore thou endurest thy inconsolable punishment; and hence it follows, But now he is comforted, and thou art tormented.

GREGORY. (in Hom. 40.) Whatsoever then ye have well in this world, when ye recollect to have done any thing good, be very fearful about it, lest the prosperity granted you be your recompense for the same good. And when ye behold poor men doing any thing blameably, fear not, seeing that perhaps those whom the remains of the slightest iniquity defiles, the fire of honesty cleanses.

CHRYSOSTOM. (Conc. 3. de Lazaro.) But you will say, Is there no one who shall enjoy pardon, both here and there? This is indeed a hard thing, and among those which are impossible. For should poverty press not, ambition urges; if sickness provoke not, anger inflames; if temptations assail not, corrupt thoughts often overwhelm. It is no slight toil to bridle anger, to cheek unlawful desires, to subdue the swellings of vain-glory, to quell pride or haughtiness, to lead a severe life. He that doeth not these things, can not be saved.

GREGORY. (ubi sup.) It may also be answered, that evil men receive in this life good things, because they place their whole joy in transitory happiness, but the righteous may indeed have good things here, yet not receive them for reward, because while they seek better things, that is, eternal, in their judgment whatever good things are present seem by no means good.

CHRYSOSTOM. (in Conc. de Laz.) But after the mercy of God, we must seek in our own endeavours for hope of salvation, not in numbering fathers, or relations, or friends. For brother does not deliver brother; and therefore it is added, And beside all this between us and yon there is a great gulf fixed.

THEOPHYLACT. The great gulf signifies the distance of the righteous from sinners. For as their affections were different, so also their abiding places do not slightly differ.

CHRYSOSTOM. The gulf is said to be fixed, because it cannot be loosened, moved, or shaken.

AMBROSE. Between the rich and the poor then there is a great gulf, because after death rewards cannot be changed. Hence it follows, So that they who would pass from hence to you cannot, nor come thence to us.

CHRYSOSTOM. As if he says, We can see, we cannot pass; and we see what we have escaped, you what you have lost; our joys enhance your torments, your torments our joys.

GREGORY. (ubi sup.) For as the wicked desire to pass over to the elect, that is, to depart from the pangs of their sufferings, so to the afflicted and tormented would the just pass in their mind by compassion, and wish to set them free. But the souls of the just, although in the goodness of their nature they feel compassion, after being united to the righteousness of their Author, are constrained by such great uprightness as not to be moved with compassion towards the reprobate. Neither then do the unrighteous pass over to the lot of the blessed, because they are bound in everlasting condemnation, nor can the righteous pass to the reprobate, because being now made upright by the righteousness of judgment, they in no way pity them from any compassion.

THEOPHYLACT. You may from this derive an argument against the followers of Origen, who say, that since an end is to be placed to punishments, there will be a time when sinners shall be gathered to the righteous and to God.

AUGUSTINE. (Qu. Ev. lib. ii. qu. 88.) For it is shewn by the unchangeableness of the Divine sentence, that no aid of mercy can be rendered to men by the righteous, even though they should wish to give it; by which he reminds us, that in this life men should relieve those they can, since hereafter even if they be well received, they would not be able to give help to those they love. For that which was written, that they may receive you into everlasting habitations, was not said of the proud and unmerciful, but of those who have made to themselves friends by their works of mercy, whom the righteous receive, not as if by their own power benefitting them, but by Divine permission.

16:27–31

27. Then he said, I pray thee therefore, father, that thou wouldest send him to my father’s house:

28. For I have five brethren; that he may testify unto them, lest they also come into this place of torment.

29. Abraham saith unto him, They have Moses and the prophets; let them hear them.

30. And he said, Nay, father Abraham: but if one went unto them from the dead, they will repent.

31. And he said unto him, If they hear not Moses and the prophets, neither will they be persuaded, though one rose from the dead.

GREGORY. (Hom. 40. in Ev.) When the rich man in flames found that all hope was taken away from him, his mind turns to those relations whom he had left behind, as it is said, Then said he, I pray thee therefore, father Abraham, to send him to my father’s house.

AUGUSTINE. (ubi sup.) He asks that Lazarus should be sent, because he felt himself unworthy to offer testimony to the truth. And as he had not obtained even to be cooled for a little while, much less does he expect to be set free from hell for the preaching of the truth.

CHRYSOSTOM. Now mark his perverseness; not even in the midst of his torments does he keep to truth. If Abraham is thy father, how sayest thou, Send him to thy father’s house? But thou hast not forgotten thy father, for he has been thy ruin.

GREGORY. (ut sup.) The hearts of the wicked are sometimes by their own punishment taught the exercise of charity, but in vain; so that they indeed have an especial love to their own, who while attached to their sins did not love themselves. Hence it follows, For I have five brethren, that he may testify to them, lest they also come into this place of torment.

AMBROSE. But it is too late for the rich man to begin to be master, when he has no longer time for learning or teaching.

GREGORY. (ut sup.) And here we must remark what fearful sufferings are heaped upon the rich man in flames. For in addition to his punishment, his knowledge and memory are preserved. He knew Lazarus whom he despised, he remembered his brethren whom he left. For that sinners in punishment may be still more punished, they both see the glory of those whom they had despised, and are harassed about the punishment of those whom they have unprofitably loved. But to the rich man seeking Lazarus to be sent to them, Abraham immediately answers, as follows, Abraham saith to him, They have Moses and the prophets, let them hear them.

CHRYSOSTOM. (Conc. 4. de Lazaro.) As if he said, Thy brethren are not so much thy care as God’s, who created them, and appointed them teachers to admonish and urge them. But by Moses and the Prophets, he here means the Mosaic and prophetic writings.

AMBROSE. In this place our Lord most plainly declares the Old Testament to be the ground of faith, thwarting the treachery of the Jews, and precluding the iniquity of Heretics.

GREGORY. (in Hom. 40.) But he who had despised the words of God, supposed that his followers could not hear them. Hence it is added, And he said, Nay, father Abraham, but if one went to them from the dead they would repent. For when he heard the Scriptures he despised them, and thought them fables, and therefore according to what he felt himself, he judged the like of his brethren.

GREGORY OF NYSSA. (lib. de Anima.) But we are also taught something besides, that the soul of Lazarus is neither anxious about present things, nor looks back to aught that it has left behind, but the rich man, (as it were caught by birdlime,) even after death is held down by his carnal life. For a man who becomes altogether carnal in his heart, not even after he has put off his body is out of the reach of his passions.

GREGORY. (ubi sup.) But soon the rich man is answered in the words of truth; for it follows, And he said unto him, If they hear not, Moses and the prophets, neither will they believe though one rose from the dead. For they who despise the words of the Law, will find the commands of their Redeemer who rose from the dead, as they are more sublime, so much the more difficult to fulfil.

CHRYSOSTOM. (ut sup.) But that it is true that he who hears not the Scriptures, takes no heed to the dead who rise again, the Jews have testified, who at one time indeed wished to kill Lazarus, but at another laid hands upon the Apostles, notwithstanding that some had risen from the dead at the hour of the Cross. Observe this also, that every dead man is a servant, but whatever the Scriptures say, the Lord says. Therefore let it be that dead men should rise again, and an angel descend from heaven, the Scriptures are more worthy of credit than all. For the Lord of Angels, the Lord as well of the living and the dead, is their author. But if God knew this that the dead rising again, profited the living, He would not have omitted it, seeing that He disposes all things for our advantage. Again, if the dead were often to rise again, this too would in time be disregarded. And the devil also would easily insinuate perverse doctrines, devising resurrection also by means of his own instruments, not indeed really raising up the deceased, but by certain delusions deceiving the sight of the beholders, or contriving, that is, setting up some to pretend death.

AUGUSTINE. (de cura pro Mortuis habenda.) But some one may say, If the dead have no care for the living, how did the rich man ask Abraham, that he should send Lazarus to his five brethren? But because he said this, did the rich man therefore know what his brethren were doing, or what was their condition at that time? His care about the living was such that he might yet be altogether ignorant what they were doing, just as we care about the dead, although we know nothing of what they do. But again the question occurs, How did Abraham know that Moses and the prophets are here in their books? whence also had he known that the rich man had lived in luxury, but Lazarus in affliction. Not surely when these things were going on in their lifetime, but at their death he might know through Lazarus’ telling him, that in order that might not be false which the prophet says; Abraham heard us not. (Isa. 63:10.) The dead might also hear something from the angels who are ever present at the things which are done here. They might also know some things which it was necessary for them to have known, not only past, but also future, through the revelation of the Church of God.

AUGUSTINE. (Quæst. Ev. ii. qu. 38.) But these things may be so taken in allegory, that by the rich man we understand the proud Jews ignorant of the righteousness of God, and going about to establish their own. The purple and fine linen are the grandeur of the kingdom. And the kingdom of God (he says) shall be taken away from you. (Rom. 10:3.) The sumptuous feasting is the boasting of the Law, in which they gloried, rather abusing it to swell their pride, than using it as the necessary means of salvation. But the beggar, by name Lazarus, which is interpreted “assisted,” signifies want; as, for instance, some Gentile, or Publican, who is all the more relieved, as he presumes less on the abundance of his resources.

GREGORY. (in Hom. 40. in Ev.) Lazarus then full of sores, figuratively represents the Gentile people, who when turned to God, were not ashamed to confess their sins. Their wound was in the skin. For what is confession of sins but a certain bursting forth of wounds. But Lazarus, full of wounds, desired to be fed by the crumbs which fell from the rich man’s table, and no one gave to him; because that proud people disdained to admit any Gentile to the knowledge of the Law, and words flowed down to him from knowledge, as the crumbs fell from the table.

AUGUSTINE. (ubi sup.) But the dogs which licked the poor man’s sores are those most wicked men who loved sin, who with a large tongue cease not to praise the evil works, which another loathes, groaning in himself, and confessing.

GREGORY. Sometimes also in the holy Word by dogs are understood preachers; according to that, That the tongue of thy dogs may be red by the very blood of thy enemies; (Ps. 68:23. Vulg.) for the tongue of dogs while it licks the wound heals it; for holy teachers, when they instruct us in confession of sin, touch as it were by the tongue the soul’s wound. The rich man was buried in hell, but Lazarus was carried by angels into Abraham’s bosom, that is, into that secret rest of which the truth says, Many shall come from the east and the west, and shall lie down with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob in the kingdom of heaven, but the children of the kingdom shall be cast into outer darkness. But being afar off, the rich man lifted up his eyes to behold Lazarus, because the unbelievers while they suffer the sentence of their condemnation, lying in the deep, fix their eyes upon certain of the faithful, abiding before the day of the last Judgment in rest above them, whose bliss afterwards they would in no wise contemplate. But that which they behold is afar off, for thither they cannot attain by their merits. But he is described to burn chiefly in his tongue, because the unbelieving people held in their mouth the word of the Law, which in their deeds they despised to keep. In that part then a man will have most burning wherein he most of all shews he knew that which he refused to do. Now Abraham calls him his son, whom at the same time he delivers not from torments; because the fathers of this unbelieving people, observing that many have gone aside from their faith, are not moved with any compassion to rescue them from torments, whom nevertheless they recognise as sons.

AUGUSTINE. (Quæst. Ev. lib. ii. qu. 39.) By the five brothers whom he says he has in his father’s house, he means the Jews who were called five, because they were bound under the Law, which was given by Moses who wrote five books.

CHRYSOSTOM. Or he had five brothers, that is, the five senses, to which he was before a slave, and therefore he could not love Lazarus because his brethren loved not poverty. Those brethren have sent thee into these torments, they cannot be saved unless they die; otherwise it must needs be that the brethren dwell with their brother. But why seekest thou that I should send Lazarus? They have Moses and the Prophets. Moses was the poor Lazarus who counted the poverty of Christ greater than the riches of Pharaoh. (Heb. 11:26.) Jeremiah, cast into the dungeon, was fed on the bread of affliction; and all the prophets teach those brethren. (Jer. 38:9.) But those brethren cannot be saved unless some one rise from the dead. For those brethren, before Christ was risen, brought me to death; He is dead, but those brethren have risen again. For my eye sees Christ, my ear hears Him, my hands handle Him. From what we have said then, we determine the fit place for Marcion and Manichæus, who destroy the Old Testament. See what Abraham says, If they hear not Moses and the prophets. As though he said, Thou doest well by expecting Him who is to rise again; but in them Christ speaks. If thou wilt hear them, thou wilt hear Him also.

GREGORY. (in Hom. 40.) But the Jewish people, because they disdained to spiritually understand the words of Moses, did not come to Him of whom Moses had spoken.

AMBROSE. Or else, Lazarus is poor in this world, but rich to God; for not all poverty is holy, nor all riches vile, but as luxury disgraces riches, so holiness commends poverty. Or is there any Apostolical man, poor in speech, but rich in faith, who keeps the true faith, requiring not the appendage of words. To such a one I liken him who oft-times beaten by the Jews offered the wounds of his body to be licked as it were by certain dogs. Blessed dogs, unto whom the dropping from such wounds so falls as to fill the heart and mouth of those whose office it is to guard the house, preserve the flock, keep off the wolf! And because the word is bread, our faith is of the word; the crumbs are as it were certain doctrines of the faith, that is to say, the mysteries of the Scriptures. But the Arians, who court the alliance of regal power that they may assail the truth of the Church, do not they seem to you to be in purple and fine linen? And these, when they defend the counterfeit instead of the truth, abound in flowing discourses. Rich heresy has composed many Gospels, and poor faith has kept this single Gospel, which it had received. Rich philosophy has made itself many gods, the poor Church has known only one. Do not those riches seem to you to be poor, and that poverty to be rich?

AUGUSTINE. (ubi sup.) Again also that story may be so understood, as that we should take Lazarus to mean our Lord; lying at the gate of the rich man, because he condescended to the proud ears of the Jews in the lowliness of His incarnation; desiring to be fed from the crumbs which fell from the rich man’s table, that is, seeking from them even the least works of righteousness, which through pride they would not use for their own table, (that is, their own power,) which works, although very slight and without the discipline of perseverance in a good life, sometimes at least they might do by chance, as crumbs frequently fall from the table. The wounds are the sufferings of our Lord, the dogs who licked them are the Gentiles, whom the Jews called unclean, and yet, with the sweetest odour of devotion, they lick the sufferings of our Lord in the Sacraments of His Body and Blood throughout the whole world. Abraham’s bosom is understood to be the hiding place of the Father, whither after His Passion our Lord rising again was taken up, whither He was said to be carried by the angels, as it seems to me, because that reception by which Christ reached the Father’s secret place the angels announced to the disciples. The rest may be taken according to the former explanation, because that is well understood to be the Father’s secret place, where even before the resurrection the souls of the righteous live with God.

Catena Aurea Luke 16