Posted on 05/23/2011 4:00:07 AM PDT by markomalley

| Kinda makes you wonder what kind of Church we would have now, if the faithful back then had kept the faith. I think there is a correlation between the lack of understanding the Church now and the turbulence within the Church back then. This is a collection of three articles. The last piece is a great article on the challenges and struggle Pope Paul had dealing with the reformers from within the Church and the Vatican. |

"Today the devil quotes the Bible," warns a lay speaker at a meeting of St. Michael's Legion, a society of Dutch Catholics who oppose reform.

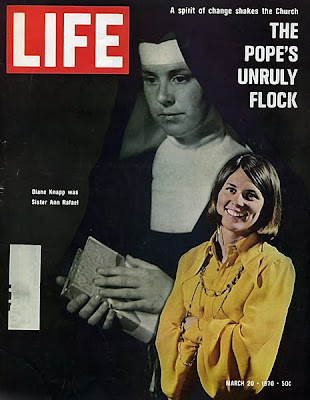

A nun's search for freedom drives her from the convent

by Martha Fay

Diane Knapp was Sister Ann Rafael, a nun, for almost four years of her life. She is no longer and her decision to leave the convent is a single, small part of a general spirit of independence threatening the established order of a Church which cherishes its orderly tradition.

Diane signed up for the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Los Angeles when she was 18, right out of high school. Now 23 and a graduate student at Berkeley, she recalls quite easily the reasons that led her to become a nun. "It seemed that it was the most natural thing to do, in terms of my background -- Catholic grade school, Catholic high school. I had thought about it, on and off, since I was 10. I think the kind of person I am would want to give herself in some way."

Her first two years in Santa Barbara, in the noitiate, were intensely difficult. "I took the whole thing very seriously. The trappings of religious life I took to be road signs for achieving it. I can remember things like saying the prayers you were supposed to say as you put on the habit, and doing it because that's what good religious did."

She went on to study at Immaculate Heart College in Los Angeles, a school run by the then 600-member order, where she lived in a huge old convent with 150 other women. "That was really hard. I felt like I was losing my identity. And there was so much going on. Everyone was questioning her role and wondering about the viability of the religious way of life." The summer of 1967 brought a series of meetings where all the members tried to work out a new concept of themselves as religious women: abandoning the habit for more modern dress, revamping the schedules and rules that had begun to hamper rather than assist them in their goals, branching out into fields other than teaching. Diane and other young sisters were encouraged to take part to an extent still unusual in religious ordres.

But the contrast she felt between atmosphere of inquiry and change within the order and still rigid constructs of the Church made living as a nun even more difficult. Her knowledge of Catholic theology and her confidence in it helped support her, yet this too was challenged. In 1965, for example the Pope issued an encyclical attacking the Dutch for their views on the exact character of the Eucharist, the sacrament involving the consecration of bread and wine. Diane was shocked, because she agreed with the Dutch. "Suddenly it was my own conscience against the Church's. That's very hard if you are supposed to be a supportive representative member of that Church." And as her own sense of self and conscience grew stronger, the meaning of freedom became more important to her. "You have to be free to be Christian in the true sense. And it's very painful not to have that freedom recognized in the Church."

Personal problems were pressing upon her at the same time. "Even though I dated through high school, I don't think I ever came to understand what it all meant until after I entered the community," she remembers. "It became very hard for me to realize that I would never be able to have a deeply personal relationship with a man and to bear children. In agonizing over it all -- the authority and the meaning of the Churh, my wanting to be a full person -- I began to have really strong guilt feelings. Was I copping out on God? It was a traumatic time. But I had to make some stab at a life that had more meaning for me. The hard thoughts jelled over the months, and in April of 1968, Diane left the order.

During the first summer out of the convent, Diane still went to daily Mass. But "there wasn't anything there. I really have hope though. Perhaps the Church will take on a new meaning in the future and maybe there will be a place in it for me. Right now I need to be out, in a new context, on a new road."

Anyone who had to take over after John XXIII, one of the best-loved men in history, would have had a problem. Inevitably he would be compared to the charismatic peasant-Pope, and inevitably he would suffer by comparison. But it would be hard to find a churchman less suited than Paul to follow John. John's pleasantly plain face could light up the most somber ecclesiastical function. Paul conveys no personal magic, even when aided by the baroque theatricality that surrounds his every public move. He is aware of this but is now resigned to the fact that there is not much he can do about it. Crossing the Atlantic in 1965 on his way to the crowds that awaited him in New York, Pope Paul, on the advice of his intimate counselors, privately practiced smiling. He did fairly well on that trip, but smiles just don't come easily to him. As soon as his attention is engaged, he slips back into the preoccupied slightly worried, turned-in-upon-himself expression that curtains his feelings even when his actual words ring with emotion. Those who know Paul personally say he is even more liberal than John, but this is not the image the public sees.

For John no problem -- whether world peace, Communism, or the divisions of Christianity -- was too complex not to be discussed in human terms. For Paul, an incurable intellectual, almost the opposite is true: no problem is too simple not to be subject to complex analysis. His remarks on everything are sown with qualifications, debilitating distinctions and cautious caveats. The style is all wrong for a church still tipsy from its first taste of freedom in centuries.

Not all the dissidents who give Paul headaches are reformers. The most recent changes in the Mass, which he highly commended, were the object of angry conservative demonstrations in Rom itself last fall. Some of the more bitter opponents of the updated liturgy have gone so far as to call Paul a heretical antipope.

The English Bishop Christopher Butler has observed: "What won the day for constitutional principles in England was that the people were prepared to go on fighting and struggling generation after generation. That is what I hope will happen in the Church." The struggle goes on even in the hierarchy, where Paul's first real confrontation, presaged by an attack on the Roman curial system by cardinal Suenens of Belgium, took place during the Bishops' Synod in Rome last fall. Paul broke tradition by attending the meetings and sitting on a level with his fellow bishops at almost every session. "Here I am," he said quietly when one bishop, reading a prepared speech, complained that the Pope should work more closely with the other bishops. After that, even the bishops who came to Rome ready for a showdown left convinced that the Pope favored their demand for greater collegiality or a larger say in the running of the universal Church.

Paul has said that he is open to any change in the Church -- except where fundamental dogma is concerned. But on birth control and clerical celibacy, two of the major issues now threatening the unity of Catholicism -- neither a matter of formal dogma and one (clerical celibacy) only disciplinary -- he still seems unbudgeable, and the more he extols tradition, the greater the demand for change. Paul is bedeviled not only by the erosion of the traditional theology, but by the breakdown of convent discipline, the creeping aceptance of divorce, the rebellious demonstrations by priests and seminarians and the growth of "underground church" defying eccelsiastical laws. He has made steady pleas for moderation among Church reformers, but the old dictum, Roma locuta, causa finita est (Rome has spoken, the case is closed), no longer applies. As a result, the Pope looks more and more like defeated man, and it is generally believed in Rome that Paul, with a sigh of relief, will step down when he reaches his 75th birthday in September 1972.

A sympathetic priest in Rome who has known Paul for 40 years said recently: "The Pope knows better than anyone else that he is a failure. He has a strong sense of history. After the turmoil following upon the Vatican Council, it will take two or three generations to reconstruct Catholicism. It is Paul's fate to sit on the papal throne at the worst possible time, beset both by those who want to change nothing. The Vatican Council released demons. Paul, poor fellow, has no friends -- at least he has no solid constituency. Right now he may be the loneliest man in the world."

In Rome these days one hears again and again Winston Churchill's famous remark that he did not become the king's first minister in order to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire. That also seems to sum up the Pope's position. But one critical Vatican monsignor thinks that Paul has missed the message here. "The Empire was going to be liquidated, no matter what Churchill said," the monsignore says. "The curial empire will be liquidated too. If the Pope were wiser he would preside over its liquidation."

Yet there is no doubt about the Pope's undivided loyalty to the age-old Vatican system. Almost from childhood he seemed to have prepared himself for a role in it. The son of zealous, comrtably middle-class parents from Brescia, he was born Gioanni Battista Montini in 1897 at the family's country home in nearby Concesio. Paul grew up in an atmosphere of good books, good talk, gentle manners, a doting mother, and a midlly liberal social concern. He began formal studies for the priesthood at 19, and it was clear from the beginning that he was not destined for a simple parish assignment. Priests from the Montinis' social milieu just didn't end up country pastors in those days.

With the special permission of the Bishop of Brescia, young Montini attended the diocesan seminary as day student, returning to the genteel comfort of his home every afternoon. Ill health was offered as the reason for this exemption from the Council of Trent's ruling that all candidates for priesthood should live under grueling discipline of seminary rules. Today, some of Paul's critics attribute his personal aloofness and seeming lack of warmth to this bypassing of the rough-and-ready camaraderie that seminarians, like soldiers, share in their all-male world.

Appointed when still in his 20s to a minor post in the Vatican Secretariat of State, a coveted assignment for a cleric on the way up, Montini was early set on the path that could lead to the papacy. But as a very young priest he became associated with some of the most progressive thinkers of pre-Vatican II Catholicism and though he served in increasingly important Vatican posts for three decades, his progressive ideas seemed on obstacle to his own advancement in the hierarchy. His vigorous defense of postwar French priests who doffed their soutanes and took their place in factories, strikes and picket lines -- the forerunners of today's clerical social activists -- made hm suspect in the eyes of the conservatives in the Holy Office, the official watchdogs of Catholic orthodoxy. He supported the worker-priests despite strong disapproval of them by both Pope Pius and the Papal Nuncio to France (Cardinal Roncalli, later John XXIII). Paul was named Archbishop of Milan, Italy's largest see, in 1954. But the touchy Pius XII broke with custom and never gave him the red hat of a cardinal. This meant that Paul was not considered for the papacy during the conclave that settled on Pope John, who then looked like an amiable conformist. Montini was the first cardinal named by John.

If Paul had followed immediately after Pius XII, he might be hailed as a great success today. He was shaped by 30 years of Vatican experience to play the papal role according to the Pius XII script. In all probability he would have done it well, adding a strong dash of modernity, and would now be compared favorably to Pius XII rather than contrasted unfavorably to John.

To Pope John himself, Monitini seemed a logical choice to take over when his "interim" regime was completed. Compared to most who had grown up in that establishment, Montini was open to new ideas and fresh theological speculation. A voracious reader, then as now, he had for years devoured the works of secular writers like Franz Kafka, Thomas Mann, Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. Montini was fascinated above all by Kafka in those days. One priest who has seen a great deal of him through his years in the Vatican says, "I think he still feels that life elsewhere is Kafka-esque and that the Church speaking through him does wlel to resist it."

But the main intellectual influence on his life has been Catholic and French. Paul identified particularly with the Christian humanism of Jacques Maritain, even when Maritain was regarded by powerful conservative churchmen as a near-heretic. Maritain, a vigorous critic clerical privilege as well as political authoritarianism, urged the Church to identify conspicuously with the poor. As Archibishop of Milan, Montini practiced what Maritain preached by frequently visiting mines and factories and became known as the "archbishop of the workers."

"Pope Paul is still a Francophile," according to the superior of a religious order who now sees him regularly. "He thiks more like a French intellectual than an Italian pastor. A typical Italian would roll with the punches better than he has been able to do. But he has been living on this bookish French diet all his life."

Paul has appointed a number of Frenchmen to high Vatican posts, including Cardinal Villot, his secretary of state. Even his Italian appointees tend to a French point of view. "What we need now," one hears more and more among the Pope's in-house critics, "is a genuine Italian pope, like John XXIII." A real Italian they argue, would know how to handle the present crisis of Catholicism, because of the Italian ability to make adjustments when a battle appears to be lost. On the contrary, the Frenchmen around Paul -- a group sometimes called the Pope's French Mafia -- reinforce his abstract, overly analytic, intellectualist assessment of the Church's problem and his disdain of compromise.

Yet even today, Paul is not as conservative in his thinking as he frequently appears to be in practice. Unlike Pope John, he writes his own encyclicals and they sometimes begin as comparatively liberal documents. But the Pope consistently falls back on the most conservative theologians in Rome to judge their orthodoxy, in order to avoid any charge that he is opening the door to heresy. Moreover, he has done little to alter the traditional cast of the Curia on which he relies. Not long ago, in fact, he made cardinals of several churchmen known for doing a bad job on their way up the ladder -- not because he approved of their record, but because above all else, he still believes in automatic seating for those who play the hierarchical game.

The Pope is reluctant to hurt people he knows personally. Consequently, the old guard in the Vatican, some of whom have long passed retirement age, are still running things pretty much the way they always did, or at least they are still trying to do so. Cardinal Ottaviani, now 79 years old and officially retired as head of the Holy Office, still carries on as if his successor's role is merely to sign official documents. To a new generation of Catholic, Paul, the onetime progressive, comes across as a weak pope who timidity is holding back the sweeping changes that John seemed to promise.

Most of the men close to him, however, do not agree that either weakness or vacillation accounts for Paul's major difficulties. "His main problem," a member of an important curial congregation says, "is that he lacks a sense of public relations. He doesn't know how to project an appealing image of himself." The Pope is probably the only major figure in the world who still does not employ a public relations adviser, and the Vatican press office is still so primitive it reinforces more than it counteracts the damaging public image of Paul as a weepy churchman, given to incessant warnings and mournfull assessments of the world.

"The Paul I know is vitally interested in everything. He may be better informed than any other leader in the world," an American cleric in the Vatican says. "He is not really a handwringer. He just seems to be -- and of course it's his own fault." The publicity-minded rector of Roman university agrees. "He's a compassionate man, but his compassion comes across as indecisiveness. He loves the world and worries about it, but even that comes across as querulousness. Basically it's a matter of image."

Then it begins once more. "You take Pope John . . ." the rector says.

Every analysis of Paul seems to end up in the comparison with John. John insisted that Monsignor Pietro Pavan, who drafted his memorable encyclical Pacem in Terris, had to write and rewrite until he, the Pope himself, could understand it. "If I can grasp it, then anyone can," he told Pavan. He once agreed with the Orthodox Patriarch Athenagoras that the biggest obstacle to Christian unity was not theology but the theologians. The elderly leaders of the two churches, who were very similar in their simplicity, agreed that the theologians made too much of doctrinal punctilio and not enough of fraternal charity. But to the degree that John gave any though to theology, he was a firm traditionalist. That was made clear in his posthumously published diary -- to the dismay of some admirers who had him marked for a cryptomodernist.

However, John unwittingly created expectations of profound theological changes which his studious, introspective, congenitally cautious successor simply cannot in conscience meet. John, who said, shrugging his shoulders, "I'm only the Pope, what can I do?" has now been transformed by his legend into a pontiff who could do anything. And the stronger the legend becomes, the weaker Paul looks.

From the Religion Moderator profile:

Types of threads and guidelines pertaining to the Religion Forum:

Prayer threads are closed to debate of any kind. If you do not specify the type of thread, it will be considered “open.”<(snip)Devotional threads are closed to debate of any kind.

Caucus threads are closed to any poster who is not a member of the caucus.

For instance, if it says “Catholic Caucus” and you are not Catholic, do not post to the thread. However, if the poster of the caucus invites you, I will not boot you from the thread. Ecumenic threads are closed to antagonism.The “caucus” article and posts must not compare beliefs or speak in behalf of a belief outside the caucus.

There is no tolerance for posters coming onto a caucus thread claiming that they were once baptized into that belief and therefore are still a member of it due to the belief saying they are - even though they are not active in that belief and notoriously dispute that belief on "open" Religion Forum threads. The same holds for those who claim they are members because of their ancestry even though they are not active in that belief and notoriously dispute it on "open" RF threads.

That behavior is finessing the guidelines, it is flame baiting. No dice.

Also, there is little to no tolerance for non-members of a caucus coming onto the caucus thread to challenge whether or not it should be a caucus. Gross disruption usually follows.

If you question whether the article is appropriate for a caucus designation, send me a Freepmail. I'll get to it as soon as I can.

To antagonize is to incur or to provoke hostility in others. Open threads are a town square. Antagonism though not encouraged, should be expectedUnlike the “caucus” threads, the article and reply posts of an “ecumenic” thread can discuss more than one belief, but antagonism is not tolerable.

More leeway is granted to what is acceptable in the text of the article than to the reply posts. For example, the term “gross error” in an article will not prevent an ecumenical discussion, but a poster should not use that term in his reply because it is antagonistic. As another example, the article might be a passage from the Bible which would be antagonistic to Jews. The passage should be considered historical fact and a legitimate subject for an ecumenic discussion. The reply posts however must not be antagonistic.

Contrasting of beliefs or even criticisms can be made without provoking hostilities. But when in doubt, only post what you are “for” and not what you are “against.” Or ask questions.

Ecumenical threads will be moderated on a “where there’s smoke, there’s fire” basis. When hostility has broken out on an “ecumenic” thread, I’ll be looking for the source.

Therefore “anti” posters must not try to finesse the guidelines by asking loaded questions, using inflammatory taglines, gratuitous quote mining or trying to slip in an “anti” or “ex” article under the color of the “ecumenic” tag.

Posters who try to tear down other’s beliefs or use subterfuge to accomplish the same goal are the disrupters on ecumenic threads and will be booted from the thread and/or suspended.

Posters may argue for or against beliefs of any kind. They may tear down other’s beliefs. They may ridicule. On all threads, but particularly “open” threads, posters must never “make it personal.” Reading minds and attributing motives are forms of “making it personal.” Making a thread “about” another Freeper is “making it personal.”

When in doubt, review your use of the pronoun “you” before hitting “enter.”

Like the Smoky Backroom, the conversation may be offensive to some.

Thin-skinned posters will be booted from “open” threads because in the town square, they are the disrupters.

Recap

Prayer threads. (snip)

Who can post? Anyone Devotional threads.What can be posted? Requests for prayers and prayers

What will be pulled? Any debate

Who will be booted? Repeat offenders.

Who can post? Anyone Caucus threads.What can be posted? Meditations

What will be pulled? Any debate

Who will be booted? Repeat offenders.

Who can post? Members of the caucus and those specifically invited Ecumenic threads.What can be posted? Anything but the beliefs of those who are not members of the caucus

What will be pulled? Reply posts mentioning the beliefs of those who are not members of the caucus. If the article is inappropriate for a caucus, the tag will be changed to open.

Who will be booted? Repeat offenders.

Who can post? Anyone Open threads – all untagged threads are open by default.What can be posted? Articles that are reasonably not antagonistic. Reply posts must never be antagonistic.

What will be pulled? Antagonistic reply posts. If the article is inappropriate for an ecumenic discussion, the tag will be changed to open.

Who will be booted? Antagonists

Who can post? Anyone What can be posted? Anything within the FR general guidelines

What will be pulled? Anything outside the FR general guidelines

Who will be booted? Thin-skinned posters

There. Is that what you had in mind???

This Religion Forum thread is labeled “Catholic/Orthodox Caucus” meaning if you are not currently, actively either Catholic or Orthodox then do not post on this thread.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.