More from those Southerners who were only concerned about slavery and weren’t at all motivated by the economics.

In a speech delivered in the Virginia Convention of 1788, Patrick Henry had predicted that the South would eventually find itself economically subjugated to the North once the latter had secured to itself a majority in the new federal Government: “This government subjects every thing to the Northern majority. Is there not, then, a settled purpose to check the Southern interest?... How can the Southern members prevent the adoption of the most oppressive mode of taxation in the Southern States, as there is a majority in favor of the Northern States?” Henry’s prediction was not long in being realized. As early as 1789, the first impost bill was introduced in Congress which protected the New England fishing industry and its production of molasses, and exhibited, in the opinion of William Grayson, “a great disposition... for the advancement of commerce and manufactures in preference to agriculture.” Thus, when the Union under the Constitution was but two months old, many Southerners felt that their States were already being obliged to serve the North as “the milch cow out of whom the substance would be extracted.” In a pamphlet published in 1850, Muscoe Russell Garnett of Virginia wrote:

The whole amount of duties collected from the year 1791, to June 30, 1845, after deducting the drawbacks on foreign merchandise exported, was $927,050,097. Of this sum the slaveholding States paid $711,200,000, and the free States only $215,850,097. Had the same amount been paid by the two sections in the constitutional ratio of their federal population, the South would have paid only $394,707,917, and the North $532,342,180. Therefore, the slaveholding States paid $316,492,083 more than their just share, and the free States as much less.

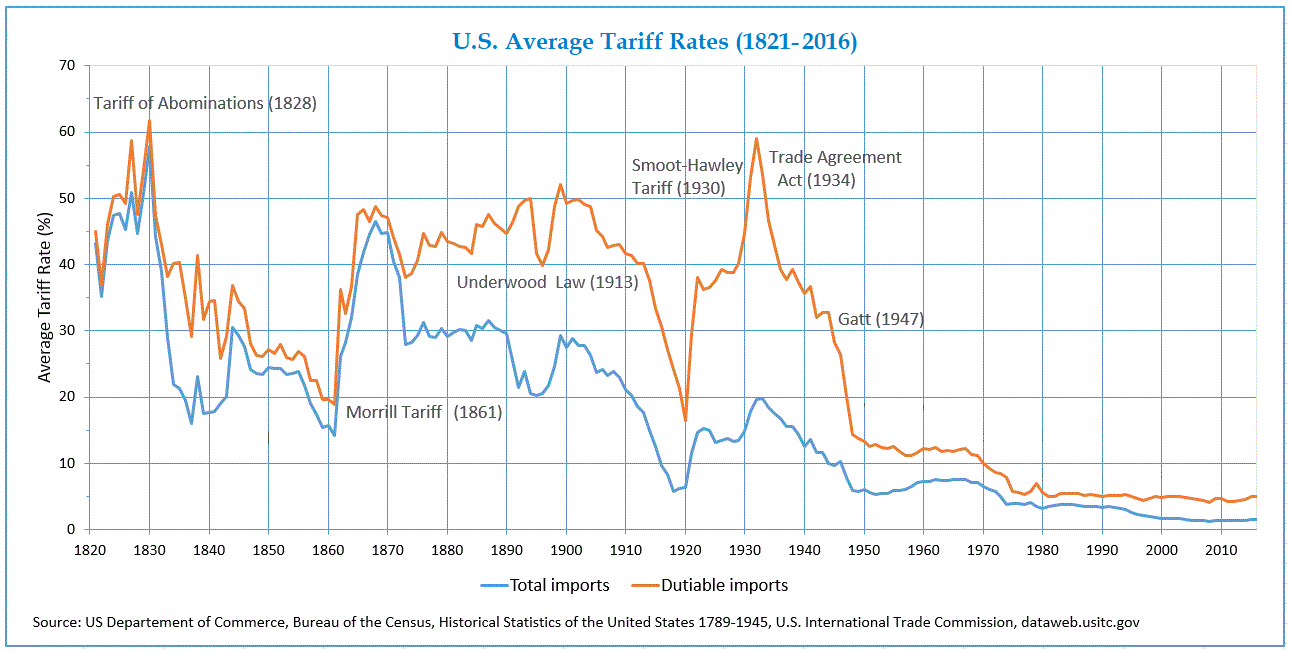

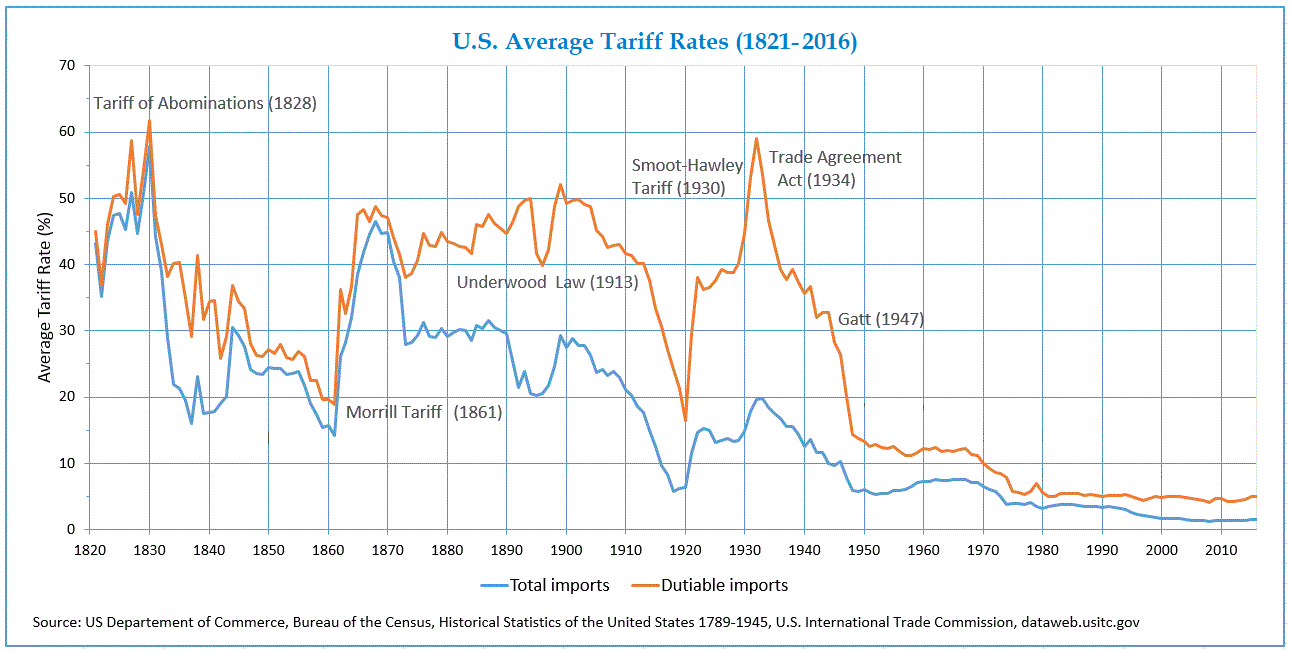

From the days of the illustrious Henry onwards, the South had generally stood in the way of the Northern goal to make such an unjust system of taxation permanent. According to John Taylor of Virginia, a high protective tariff system, like that which existed in Great Britain, was “undoubtedly the best which has ever appeared for extracting money from the people; and commercial restrictions, both upon foreign and domestic commerce, are its most effectual means for accomplishing this object. No equal mode of enriching the party of government, and impoverishing the party of people, has ever been discovered.” Nevertheless, the North clung tenaciously to its protectionist policy and managed to push through the tariff legislation of 1828 which provoked South Carolina to resistance to the general Government and nearly to secession from the Union during the Administration of Andrew Jackson. It should be noted that, by 1828, the public debt was near to extinction and, at the current rate of taxation on imported goods, a twelve to thirteen million dollar annual surplus would have been created in the Treasury. Thus, the excuse for a high tariff system as a source of Government revenue was a flimsy one at best; the so-called “Tariff of Abomination” really served no other purpose than to “rob and plunder nearly one half of the Union, for the benefit of the residue.” James Spence of London explained the effects of such a high tariff on the Southern economy:

This system of protecting Northern manufactures, has an injurious influence, beyond the effect immediately apparent. It is doubly injurious to the Southern States, in raising what they have to buy, and lowering what they have to sell. They are the exporters of the Union, and require that other countries shall take their productions. But other countries will have difficulty in taking them, unless permitted to pay for them in the commodities which are their only means of payment. They are willing to receive cotton, and to pay for it in iron, earthenware, woollens. But if by extravagant duties, these be prohibited from entering the Union, or greatly restricted, the effect must needs be, to restrict the power to buy the products of the South. Our imports of Southern productions, have nearly reached thirty millions sterling a year. Suppose the North to succeed in the object of its desire, and to exclude our manufactures altogether, with what are we to pay? It is plainly impossible for any country to export largely, unless it be willing also, to import largely. Should the Union be restored, and its commerce be conducted under the present tariff, the balance of trade against us must become so great, as either to derange our monetary system, or compel us to restrict our purchases from those, who practically exclude other payment than gold. With the rate of exchange constantly depressed, the South would receive an actual money payment, much below the current value of its products. We should be driven to other markets for our supplies, and thus the exclusion of our manufactures by the North, would result in a compulsory exclusion, on our part, of the products of the South.

This is a consideration of no importance to the Northern manufacturer, whose only thought is the immediate profit he may obtain, by shutting out competition. It may be, however, of very extreme importance to others — to those who have products they are anxious to sell to us, who are desirous to receive in payment, the very goods we wish to dispose of, and yet are debarred from this. Is there not something of the nature of commercial slavery, in the fetters of a system that prevents it? If we consider the terms of the compact, and the gigantic magnitude of Southern trade, it becomes amazing, that even the attempt should be made, to deal with it in such a manner as this.

George McDuffie of South Carolina stated in the House of Representatives, “If the union of these states shall ever be severed, and their liberties subverted, historians who record these disasters will have to ascribe them to measures of this description. I do sincerely believe that neither this government, nor any free government, can exist for a quarter of a century under such a system of legislation.” While the Northern manufacturer enjoyed free trade with the South, the Southern planter was not allowed to enjoy free trade with those countries to which he could market his goods at the most benefit to himself. Furthermore, while the six cotton States — South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas — had less than one-eighth of the representation in Congress, they furnished two-thirds of the exports of the country, much of which was exchanged for imported necessities. Thus, McDuffie noted that because the import tariff effectively hindered Southern commerce, the relation which the Cotton States bore to the protected manufacturing States of the North was now the same as that which the colonies had once borne to Great Britain; under the current system, they had merely changed masters.

Robert Barnwell Rhett, who served in the House of Representatives and then in the Senate, said in 1850: “The great object of free governments is liberty. The great test of liberty in modern times, is to be free in the imposition of taxes, and the expenditure of taxes.... For a people to be free in the imposition and payment of taxes, they must lay them through their representatives.” Consequently, because they were being taxed without corresponding representation, the Southern States had been reduced to the condition of colonies of the North and thus were no longer free. The solution was determined by John Cunningham to exist only in independence:

The legislation of this Union has impoverished them [the Southern States] by taxation and by a diversion of the proceeds of our labor and trade to enriching Northern Cities and States. These results are not only sufficient reasons why we would prosper better out of the union but are of themselves sufficient causes of our secession. Upon the mere score of commercial prosperity, we should insist upon disunion. Let Charleston be relieved from her present constrained vassalage in trade to the North, and be made a free port and my life on it, she will at once expand into a great and controlling city.

In a letter to the Carolina Times in 1857, Representative Laurence Keitt wrote, “I believe that the safety of the South is only in herself.” James H. Hammond likewise stated in 1858, “I have no hesitation in saying that the Plantation States should discard any government that makes a protective tariff its policy.”

John H. Reagan of Texas, who would later become Postmaster-General of the Confederate Government, expressed similar sentiments when addressing the Republican members of the House of Representatives on 15 January 1861:

You are not content with the vast millions of tribute we pay you annually under the operation of our revenue laws, our navigation laws, your fishing bounties, and by making your people our manufacturers, our merchants, our shippers. You are not satisfied with the vast tribute we pay you to build up your great cities, your railroads, your canals. You are not satisfied with the millions of tribute we have been paying you on account of the balance of exchange which you hold against us. You are not satisfied that we of the South are almost reduced to the condition of overseers of northern capitalists. You are not satisfied with all this; but you must wage a relentless crusade against our rights and institutions....

We do not intend that you shall reduce us to such a condition. But I can tell you what your folly and injustice will compel us to do. It will compel us to be free from your domination, and more self-reliant than we have been. It will compel us to assert and maintain our separate independence. It will compel us to manufacture for ourselves, to build up our own commerce, our own great cities, our own railroads and canals; and to use the tribute money we now pay you for these things for the support of a government which will be friendly to all our interests, hostile to none of them

See that last quote....to manufacture for ourselves? Yet some would tell us Southerners weren’t at all interested in industrialization - nevermind that it had taken the western world by storm by the middle of the 19th century.

FLT-bird:

"More from those Southerners who were only concerned about slavery and weren’t at all motivated by the economics." Well... just so we're clear about this: nobody denies that economics played a role, of course it did, always does.

But economics alone do not usually start or sustain shooting wars, certainly not amongst prosperous countries, there's simply not enough passion in just economics to sustain orgies of bloodletting and treasure exhaustion.

Remember, the term "trade war" is just a metaphor, even when hundreds of billions of dollars per year are involved -- as, for example with China & several other trading "partners" today -- we might expect, in effect, boycotts or even worker strikes, which will cause economic pain, but that's a far cry from international shootouts at the OK coral.

War requires something much more existential, something closer to home, something more threatening to average citizens.

In 1860 that "something" was slavery and Fire Eaters rode it for all it was worth.

FLT-bird quoting Patrick Henry to Virginia's 1788 Constitution ratifying convention: "This government subjects every thing to the Northern majority.

Is there not, then, a settled purpose to check the Southern interest?...

How can the Southern members prevent the adoption of the most oppressive mode of taxation in the Southern States, as there is a majority in favor of the Northern States?” "

Henry opposed the new Constitution, voted against ratification.

Others didn't buy Henry's arguments and voted to ratify.

And Henry was suspicious of Northerners, but this particular "quote" seems dubious because:

- After serving in the Continental Congress from 1774 to 1775 Henry was never again elected to a national Congress, and yet here is quoted as if familiar with its factions.

- Factions in the 1st US Congress were roughly 2/3 Pro & 1/3 Anti-administration, with 2/3 of Anti-Administration legislators being Southern.

However, then as always there were political cross-dressers and trans-party "moderates".

- This particular Patrick Henry "quote" might well refer the 1st Congress' first tax, the Tariff of 1789.

That was acknowledged at the time as favoring Northerners at Southern expense, but Anti-administration Virginia Congressman James Madison lead the bill's supporters and it passed with just under 2/3 of the vote.

My point here is, the basic North-South division in US politics was already seen in the 1st Congress, but it was not then, or ever, hard and fixed.

Anti-Administration Virginia Congressman Madison lead the effort for higher tariffs in 1789, just as in 1828 Southerners Calhoun & Jackson originally supported the "Tariff of Abominations" and in 1860 some Southerners supported the Morrill Tariff, while some Northerners opposed all of those.

Indeed, the great success of Jefferson's Anti-administration party after 1800, now renamed "Democratic Republicans", came from the fact they received far more Northern support in states like Massachusetts, New York & Pennsylvania than Federalists got in the South.

And in 1801 as in most of the next 60 years, Southerners were the majority of their majority Democrat party.

Bottom line: basic North-South differences were there already in 1789, but were never as hard & fast as this alleged quote from Patrick Henry wants us to believe.

Tariffs were always "politics as usual", never a casus belli: