Shavua Tov.

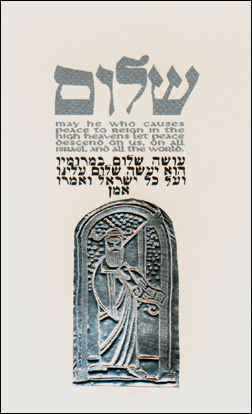

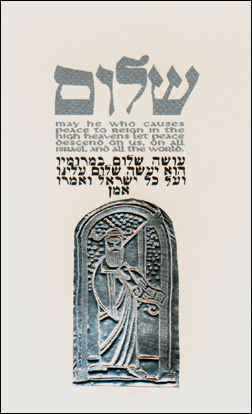

Wishing all our Jewish troops, veterans, families, allies, friends, and Canteeners

a peaceful and prosperous week.

Shavua Tov.

Wishing all our Jewish troops, veterans, families, allies, friends, and Canteeners

a peaceful and prosperous week.

Prayers for our troops, veterans, families, allies, friends, and Canteeners

for a safe and peaceful week ahead.

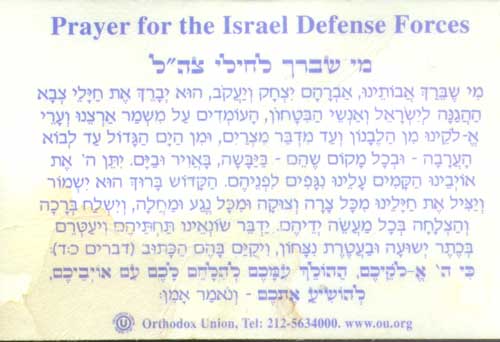

He Who blessed our forefathers Abraham, Isaac and Jacob - may He bless the fighters of the Israel Defense Force, who stand guard over our land and the cities of our G-d from the border of the Lebanon to the desert of Egypt, and from the Great Sea unto the approach of the Aravah, on the land, in the air, and on the sea.

May HASHEM cause the enemies who rise up against us to be struck down before them. May the Holy One, Blessed is He, preserve and rescue our fighting men from every trouble and distress and from every plague and illness, and may He send blessing and success in their every endeavor.

May He lead our enemies under their sway and may He grant them salvation and crown them with victory. And may there be fulfilled for them the verse: For it is Hashem, your G-d, Who goes with you to battle your enemies for you to save you.

G-d bless and keep your children safe, Alouette.

Hector Berlioz wrote a Requiem that has been described as "bizarre." He wrote for an oversized orchestra, oversized chorus, four separate brass bands placed in four balconies, separate tympani sections, and a tenor suspended from a catwalk. Despite these eccentricities, it's an amazing piece of music.

Fearing Mozart's precedent, Berlioz sets the Kyrie as plainchant. But it's the Dies irae where he pulls out all the stops. It starts in A minor with the sopranos stating the theme softly, joined by the basses and tenors.

At 2:41, it goes up a semi-tone to B-flat minor, and the tenors take up the march.

At 3:54, it goes up to D minor, and the choir works the theme up as a canon.

Then at 5:11 all hell breaks loose. The key changes to E-flat, and four separate brass bands in the balconies take over a grand fanfare, leading to separate sections of tympani accompanying the chorus in the Tuba mirum. Choristers here are totally dependent on the conductor because they can't hear a thing over all the kettle drums going at once.

At 7:30, the choir gets a break and sings Mors stupebit quietly for the buildup to the second fanfare. For the second episode, the basses and brass bands alternate parts leading up to the kettle drums.

At 11:05, the movement ends quietly with menacing figures on the lower strings. The sense is, "Did I just really sing that?"

This is Robert Shaw conducting the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and Chorus.

There is a long and honored tradition of singing the Rex tremendae as "Sex tremandae" in rehearsal. In this video, you can see just how big the forces are for this piece. This is why in any city it will not be performed more often than every 30 or 40 years.

This is Colin Davis conducting the combined orchestras and choruses of the Paris Conservatory and the London Music College.

The Lacrymosa is written in 9/8. Usually this is three groups of three to the bar, but here Berlioz writes it as nine straight beats with the strong beat on six. It's an odd rhythmic effect. He brings in the chorus one fach at a time. (Try saying that German word and not make it sound dirty.)

At 2:13, an interlude turns from A minor to C Major. The basses then take the pulse.

But at 4:36 things return to A minor, and this time the chorus is accompanied by interjections from the tympani section and the brass bands.

At 6:22, the C Major section returns in A Major.

At 8:08, there is a titanic battle of heaven versus hell in A minor as the chorus insistently sings an F (heaven) while the brasses insist equally on E (hell). The chorus sings the Lacrymosa line in unison and then in thirds. Switching decisively to A Major, at 9:23, Berlioz plays his trump card. He staggers the chorus and orchestra a half beat off each other to take advantage of the echo in the church as heaven wins the battle. The chorus ends in unison, and the vision fades into silence.

This is Shaw again.

Remember that tenor suspended from a catwalk? Berlioz uses him to represent an angel in the Sanctus. Having stayed away from fugues thus far (remember Mozart's Kyrie?) Berlioz writes a fugue for chorus for the Hosanna. The key is D-flat. The second time through the Sanctus, the percussion punctuates respectfully. The second time through the Hosanna, Berlioz extends the fugue into a bravura finish.

This is tenor Leopold Simoneau with Charles Munch conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra & New England Conservatory Chorus.

God Bless our military men and women who have given their all.

Thanks, unique.