Skip to comments.

Emancipation: January 1, 1863

Townhall.com ^

| January 1, 2012

| Ken Blackwell

Posted on 01/01/2013 6:56:33 AM PST by Kaslin

Editor's Note: This column was coauthored by Bob Morrison.

President Abraham Lincoln had been warned by Gen. George B. McClellan not to interfere with the institution of slavery. McClellan was a “War Democrat,” willing to fight to preserve the Union, but unwilling to do anything about the root cause of the rebellion that threatened the life of the nation.

Ironically, it was McClellan’s victory at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, that had given Lincoln the opportunity he needed to issue his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. In that document, the President warned rebellious states in the South that they would have their slaves freed if they did not cease their insurrection against the federal government and once again obey the laws of the Union.

That hundred-day period had been a difficult one for President Lincoln. There would be political reverses in the mid-term congressional elections that fall. Democrats campaigned on the slogan “The Union as it was and the Constitution as it is.” That meant slavery would be secure in all the states where it then existed. They picked up congressional seats and won key state governorships.

And then, there was the disastrous Union defeat at Fredericksburg, Virginia. Thousands of Union soldiers died in thirteen fruitless charges against Marye’s Heights. An extraordinary appearance of the Northern Lights on the night of that battle led people to say the very heavens were draped in mourning.

Now, on January 1, 1863, Lincoln proved true to his word on Emancipation. But, as he sat down to sign the engrossed copy of the historic document, he noted an error in the text. Lincoln knew that the U.S. Supreme Court was hostile to Emancipation. If there was a single error, Lincoln knew the pro-slavery Chief Justice Roger B. Taney would strike down the Emancipation Proclamation. So he ordered it re-copied for signature later that same day.

Meanwhile, President Lincoln had to stand for hours shaking thousands of hands in the traditional New Year’s Day reception at the White House. When he came back to sign the Emancipation Proclamation, his hand was shaking. As his puzzled colleagues looked on,he exercised his weary arm.

He explained: “If I am remembered for anything, it will be for this act and my whole soul is in it.” He did not want future generations to see a feeble signature and say he hesitated. So he signed it “Abraham Lincoln.” He wrote out his full name, not signing it as he usually did, “A. Lincoln.”

January 1, 2013, the National Archives places the Emancipation Proclamation on rare public display, the text is hardly legible, the victim of age and light. But Abraham Lincoln stands out clearly.

Some cynics today say Lincoln freed no slaves where he had power and all the slaves where he did not. Then, too, the London newspapers adopted a snarky tone: “The high principle of Mr. Lincoln’s proclamation is that a man may not own a man unless he is loyal to Mr. Lincoln’s government.”

That criticism was as ignorant as it was unfair. Lincoln was no despot. He knew that he could not constitutionally deprive loyal citizens of their slaves so long as they obeyed the laws. He pleaded and cajoled the congressmen from the loyal slave states of Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware. They stubbornly refused his offers of compensated emancipation.

Lincoln was an able lawyer who new his brief. He had been a reader of Richmond newspapers for years. When secessionist editors boasted that the South could outlast the North because they could send all their young men into the army, while slaves would work the farms and factories, Lincoln took note.

Because the rebels themselves claimed slavery was a military asset, Lincoln knew he was on solid ground in freeing those slaves. His Emancipation Proclamation was a constitutional exercise of his powers as commander-in-chief of the army and navy. He justified it as an act of military necessity.

Abraham Lincoln is remembered as the Great Emancipator. He knew that the advance of the Union armies would bring freedom to millions.

Lincoln’s bold black signature had done this. And he would do more. As the movie, Lincoln, so clearly shows, the president was the prime mover behind the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution. That measure ended slavery in every state. It’s a shame that the able writers and directors of this new movie did not show Lincoln signing that amendment, too. A president’s signature is not necessary for a constitutional amendment, but Lincoln once again had his whole heart and soul in it.

This is the day, January 1, 1863, one hundred fifty years ago, that changed America forever. From that date onward, Father Abraham’s armies, the armies of the United States, became armies of liberation. Those soldiers, black and white, carried freedom in their haversacks.

TOPICS: Editorial

KEYWORDS: abrahamlincoln; america; emancipation; kkk; klan; preservetheunion; slavery

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first previous 1-20, 21-40, 41-60, 61-80 next last

To: Scoutmaster

Yes, the economics of slavery and its imposition on an increasingly unwilling population.

41

posted on

01/02/2013 3:24:30 PM PST

by

rockrr

(Everything is different now...)

To: Scoutmaster; rockrr

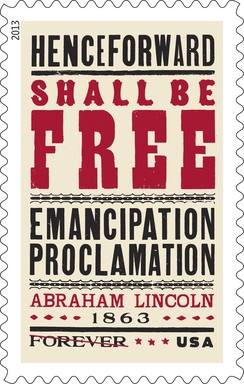

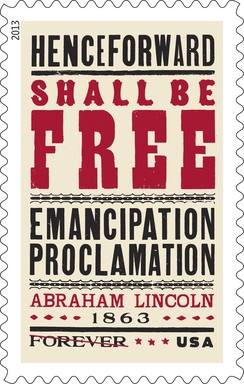

Why it is a pun to put 'Forever' on an Emancipation Proclamation 'Forever' stamp?

The famous phrase freeing the slaves in rebel territories is "then, thenceforward, and forever free."

So here we have the "forever" of the now-familiar "forever stamps" completing the idea "free forever."

Maybe you had to be there ... or have taken a lot of useless lit classes.

__________________

Anyway, here is the last commemorative stamp:

Have 50 years really gone by since?

You could mail a first class letter with one of these.

Check out the price.

42

posted on

01/02/2013 3:34:17 PM PST

by

x

To: rockrr; donmeaker; Sherman Logan

When people say the war started over economics, I assume they’re using the word economics as an euphemism for slavery.

43

posted on

01/02/2013 3:39:34 PM PST

by

Scoutmaster

(You knew the job was dangerous when you took it)

To: x

'Forever' stamps - stamps which you can buy at today's price yet use to mail a first-class letter even after postal rates increase - have always had the word 'forever' on them.

I doubt the 'forever' on my Lady Liberty Forever Stamps meant that I could use it forever, but the 'forever' on the Emancipation Forever Stamps was cleverly drawn from "then, thenceforward, and forever free."

Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.

44

posted on

01/02/2013 3:44:16 PM PST

by

Scoutmaster

(You knew the job was dangerous when you took it)

To: x

45

posted on

01/02/2013 4:14:13 PM PST

by

Scoutmaster

(You knew the job was dangerous when you took it)

To: donmeaker

I’ve seen the $4B number tossed about, but I doubt its accuracy.

There were about 4M slaves, and $4B would require an average price of $1000. My understanding is that is more than a little high, so I use $750 instead.

Here’s a really interesting article about slave prices. It points out that comparing prices from one period to another is intrinsically challenging, but using three possible ways of doing so, the $500 average price of a slave in 1850 equates to somewhere between $11,000 and $162,000 today.

http://www.measuringworth.com/slavery.php

I don’t think people realize what happened in the South when the slaves were freed. The South had been investing its capital into slaves for many decades, and all of that capital - as capital - suddenly disappeared. Couldn’t be used as collateral for a loan or any other purpose.

So while the productive capacity of the region, deducting of course for the immense physical damage caused by the war, was perhaps theoretically higher, decades of capital accumulation had disappeared.

Think of the financial pain caused by the slight decline in wealth caused by our recent housing bubble burst. I have seen figures of perhaps 5% loss in national wealth, much higher of course for many individuals.

When the slaves were freed, the South lost perhaps 1/3 or more of its prewar capital.

To: Scoutmaster

Well, "Freedom Forever" "Liberty Forever" was sort of the same thing, but I guess you just didn't notice, being so depressingly literal-minded.

The first "forever stamps" were those "First Class Forever" Liberty Bell stamps -- not much ambiguity there.

47

posted on

01/02/2013 4:36:27 PM PST

by

x

To: Sherman Logan

(That presumes that all the slaves were in states that left the union, and that all the business property invested in union states had nothing to do with slavery, but the disparity is so stark, the argument survives the inaccuracy of the statistics.)

48

posted on

01/02/2013 5:02:52 PM PST

by

donmeaker

(Blunderbuss: A short weapon, ... now superceded in civilized countries by more advanced weaponry.)

To: x

What was the USPS's thought behind the Ronald Reagan 100th Birthday Freedom stamp?

Those were issued in 2011 - in the middle of the First Term of Destruction. May I be 'depressingly literal-minded' and posit that they were to celebrate the centenary of Reagan's birth?

49

posted on

01/02/2013 5:03:48 PM PST

by

Scoutmaster

(You knew the job was dangerous when you took it)

To: x

I don’t buy stamps much anymore, (goodbye USPS) but if I do, I’ll get some of them. Who knows with the way things are going. That 45 cent ‘forever’ stamp may be worth $100 before long. ;~))

50

posted on

01/02/2013 6:07:59 PM PST

by

Ditto

To: donmeaker; Ditto; Scoutmaster; rockrr

I wonder if the thousands black soldiers that served in the CSA thought it was all about slavery?

A letter by a Federal officer:

Col. Giles Smith commanded the First Brigade and Col. T. Kilby Smith, Fifty-fourth Ohio, the Fourth. I communicated to these officers General Sherman's orders and charged Colonel Smith, Fifty-fourth Ohio, specially with the duty of clearing away the road to the crossing and getting it into the best condition for effecting our crossing that he possibly could. The work was vigorously pressed under his immediate supervision and orders, and he devoted himself to it with as much energy and activity as any living man could employ. It had to be prosecuted under the fire of the enemy's sharpshooters, protected as well as the men might be by our skirmishers on the bank, who were ordered to keep up so vigorous a fire that the enemy should not dare to lift their heads above their rifle-pits; but the enemy, and especially their armed negroes, did dare to rise and fire, and did serious execution upon our men. The casualties in the brigade were 11 killed, 40 wounded, and 4 missing; aggregate, 55. Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

D. STUART, Brigadier-General, Commanding."

Congressional Testimony of Nathan Bedford Forrest before the Congress Joint Select Committee, Ku Klux conspiracy: Report of the joint Select Committee to Inquire into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States, Made to Both Houses of Congress. 42nd Congress; 2nd session, Senate Report 41, Volume 13; Washington, D.C. (1872) Nathan Bedford Forrest who had many Black Confederates with him Nathan Beford Forrest

I said to forty-five colored fellows on my plantation that it was a war upon slavery, and that I was going into the army; that if they would go with me, if we got whipped they would be free anyhow, and that if we succeeded and slavery was perpetuated, if they would act faithfully to me to the end of the war, I would set them free . . . Eighteen months before the war closed I was satisfied that we were going to be defeated and, and I gave them their free papers, for I fear I might be killed . . . No finer Confederates rode with me. {Emphasis Added}

When Forrest surrendered, there were 65 Free Men of Color riding with his forces. It is noted that all of these men rode with Gen. Forrest until the end of the war and not one ever signed an Oath of Loyalty or was “reconstructed.”

51

posted on

01/03/2013 4:16:00 AM PST

by

central_va

( I won't be reconstructed and I do not give a damn.)

To: Sherman Logan; donmeaker

Sherman Logan:

"I’ve seen the $4B number tossed about, but I doubt its accuracy." In Huston's book, "Calculating the Value of the Union", his table 2.3 (page 28) lists 1860 census results for values of various categories of property, and "property", ahem.

These numbers are for the entire Union:

- $6.6 billion value of all farms

- $3.0 billion for slaves

- $1.1 billion value of livestock

- $1.2 billion railroads

- $1.05 billion manufacturing

- $ .25 billion value of farm implements

- $ .23 billion bank capital

- $ .03 billion home productions

- $13.5 billion total

Sherman Logan: "the $500 average price of a slave in 1850 equates to somewhere between $11,000 and $162,000 today."

In overall economic terms, it's more than that.

For real apples-to-apples comparisons, I think you need to look at their "relative share of GDP" number, which corresponds to "how much national effort went into this project", and that number would today be $1,740,000.

So four million slaves then, at $500 per slave, corresponds to about $7 trillion dollars today -- a pretty hefty sum.

But the census total of $3 billion suggests an average cost of $750 and equates to more than $10 trillion today.

Finally, we should note again that $3 billion in slaves was more than the value of all Southern lands themselves, and more than the total Northern investment in railroads and manufacturing.

So the potential loss of such value through some actions in Washington DC, was certainly a matter of utmost concern, not just to large slave holders themselves (relatively few), but to every Southerner whose prosperity depended on their "peculiar institution".

52

posted on

01/03/2013 4:46:30 AM PST

by

BroJoeK

(a little historical perspective....)

To: BroJoeK

Interesting.

Assuming the numbers are more or less accurate, the value of the slaves alone (not counting the value of their production) was 3x the capital invested in the overpoweringly dominant industrial sector located largely in the North.

/s

The South was indeed oppressed and exploited after the War, and I believe people tend to move this oppression back in time and assume it was the same before the War.

But the truth is, as has been pointed out on this thread several times, that the South was actually dominant and rebelled because of seeing the writing on the wall that this dominance was ending, not because of intolerable oppression.

I am always amused by those who repeat the canard that the South seceded to resist expansion of federal power, when the actual issue that broke apart the Democratic Party, the last institution joining the sections, was a demand for expansion of federal power.

The southern delegates demanded that the Party add to its platform planks insisting that northern state laws giving fugitive slaves something resembling due process be repealed, and that a federal slave code impose slavery throughout the territories, using federal troops to protect the institution against the wishes of the inhabitants if necessary.

To: Sherman Logan

Sherman Logan:

"The southern delegates demanded that the Party add to its platform planks insisting that northern state laws giving fugitive slaves something resembling due process be repealed, and that a federal slave code impose slavery throughout the territories, using federal troops to protect the institution against the wishes of the inhabitants if necessary." Hmmmmm.... I had not read that, do you have a source?

Surely what those "fire eaters" wanted -- who walked out of the first Democrat convention in Charleston, in April 1860 -- they got in their platform, in the rump Democrat convention, in Richmond in June?

Did Breckenridge's platform include the planks you just mentioned?

54

posted on

01/03/2013 7:47:55 AM PST

by

BroJoeK

(a little historical perspective....)

To: BroJoeK

I may have misremembered the Personal Liberty Laws of northern states as specifically being a big issue at the convention, although they were an enormous irritant to southerners, even though they had little actual effect. To be fair, these laws were entirely unconstitutional. (Which does not speak well for the Constitution.)

But I was entirely right about a federal slave code for the territories being demanded at the convention. When the demand was voted down, the southern delegates walked out of the Charleston convention.

Democrats tried again in Baltimore, and this time the southerners, and some of the northern delegates, walked out over the issue of whether all the delegates who had bolted from Charleston should be reseated or not. The seceding delegates then nominated Breckinridge for President.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1860_Democratic_National_Convention

The issue is covered well in Battle Cry of Freedom, which I just finished reading. The 3-way splintering of the Democratic Party pretty much ensured Lincoln’s election, which was probably the motive for some of the southern delegates behaving as they did. They wanted secession, and ensuring Lincoln’s election was the way to get it.

To: central_va

Although I’m not seeing anyone on these boards stating that it was “all about slavery” (you do understand the difference between proximate cause and contributory cause, right?) the correct answer to your specific question could most likely be a resounding “yes”. Look at your own evidence.

Forrest tells his slaves that the war “was a war upon slavery” and that their future prospects and indeed their very lives depend upon the outcome. How could they think anything else?

Interestingly, even though individuals like Forrest and REL advocated emancipation in exchange for service, the official csa policy stubbornly refused to acknowledge the necessity - right up to the end.

56

posted on

01/03/2013 8:33:50 AM PST

by

rockrr

(Everything is different now...)

To: rockrr; central_va

A slave ordered to fight for the South was no more a volunteer than a horse or mule. His being armed says absolutely nothing about his beliefs or choices. That is the whole point and horror of slavery, that it removes free will from humans to whom God granted it.

Now admittedly an armed slave had the option of shirking, or even fragging during battle, but no more so than any other soldier. Including of course draftees who were equally given no choice of whether to serve.

To: Sherman Logan

There sure were a lot of slave revolts during the Civil War. To numerous to document. You would expect that in a time of war when the resources for recovering a runway was slim. Oh wait, there were zero slave revolts during the Civil War, so never mind.

58

posted on

01/03/2013 9:27:26 AM PST

by

central_va

( I won't be reconstructed and I do not give a damn.)

To: central_va

I don’t know anybody who ever claimed there were slave revolts during the war, an enormous credit to the slaves, BTW.

There was, however, literally from the first days of the war, massive flight to Union lines by slaves whenever it became practical, and sometimes when it wasn’t.

This doesn’t exactly show much enthusiasm for their previous condition.

To: Sherman Logan

That is the whole point and horror of slavery, that it removes free will from humans to whom God granted it.Amen.

60

posted on

01/03/2013 12:55:11 PM PST

by

Scoutmaster

(You knew the job was dangerous when you took it)

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first previous 1-20, 21-40, 41-60, 61-80 next last

Disclaimer:

Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual

posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its

management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the

exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.

FreeRepublic.com is powered by software copyright 2000-2008 John Robinson