Posted on 06/24/2009 10:54:57 PM PDT by neverdem

Had Americans been able to stop obsessing over the color of Barack Obama's skin and instead paid more attention to his cultural identity, maybe he would not be in the White House today. The key to understanding him lies with his identification with his father, and his adoption of a cultural and political mindset rooted in postcolonial Africa.

2 Articles??

A story in the Star-Bulletin on the day he left, June 22, said Obama planned a several-weeks grand tour of mainland universities before he arrived at Harvard to study economics on a graduate faculty fellowship. The story did not mention that he had a wife and an infant son.

Many years later, Barack Jr., then in high school, found a clipping of the article in a family stash of birth certificates and old vaccination forms. Why wasn’t his name there, or his mother’s? He wondered, he later wrote, “whether the omission caused a fight between my parents.”

On his way east, Obama stopped in San Francisco and went to dinner at the Blue Fox in the financial district with Hal Abercrombie, who had moved to the city with his wife, Shirley.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/08/22/AR2008082201679_5.html

From your Journal of American History link:

“[Tom Schachtman] has found that the elder Obama came in 1959 with support from the aasf but appears to have been routed a different way as he made his way to the University of Hawaii.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~

From Tom Schachtman’s book, Airlift:

“As far as can be determined from incomplete records, Mrs. Roberts and Miss Mooney paid his fare to Hawaii and provided a partial scholarship.

Mboya, while unable to transport the twenty-three-year-old, did put him on the AASF list to receive one of the handful of scholarships contributed by the former baseball star Jackie Robinson, which the Scheinman foundation was administering, and encouraged him to look to the AASF for further help if needed, which he later did. “

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

From LLI (now ProLiteracy.Org):

With a letter of recommendation provided by Mooney and initial financial support from Laubach Literacy International 5, Obama’s application to study economics at the University of Hawaii was accepted. He was admitted on a scholarship and started his studies in the fall of 1959.

During his time in Hawaii and in need of support as a full time student, Obama reached out to Laubach Literacy International for additional financial assistance. In the spirit of the organizational belief that it could help “build tomorrow’s teams in centers and abroad” the organization awarded Obama a Fund Scholarship to support to his United States studies.

The record of this funding was noted in the organization’s 1961 Annual Report: “Barack Obama, from Kenya, is in an undergraduate program at the University of Hawaii. An honor student, Barack may come later to Syracuse for literacy journalism.” 6 Because of her deep belief in his skills and abilities, Mooney also provided personal financial assistance to Obama to support his tenure at the University of Hawaii.

A reversal of fortune?

#381: A story in the Star-Bulletin on the day he left, June 22, said Obama planned a several-weeks grand tour of mainland universities before he arrived at Harvard to study economics on a graduate faculty fellowship. The story did not mention that he had a wife and an infant son.

“A reversal of fortune?”

or a useful fib -— feigning interest in field dear to Mooney’s heart for $$ support.

Mboya (new financial allegiance? or original intentions)

LLI’s Elizabeth Mooney Kirk wrote to Tom Mboya in May 1962 to request additional funds to “sponsor Barack Obama for graduate study, preferably at Harvard.” She said she would “like to do more” to assist the young man but had two stepchildren ready for college.

Kirk’s letter worked and Obama Sr. was offered a scholarship (from Tom Mboya in Kenya) to pursue a doctorate at Harvard.

http://atlasshrugs2000.typepad.com/atlas_shrugs/2008/10/how-could-stanl.html

“...On his way east, Obama stopped in San Francisco and went to dinner at the Blue Fox in the financial district with Hal Abercrombie, who had moved to the city with his wife, Shirley.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/08/22/AR2008082201679_5.html

Don’t know why, but that link to WP freezes at the headline for me.

Is that the occasion where Hal Abercrombie describes obama sr’s bad behaviour in the restaurant? If so, would you please post that excerpt here?

Kirk’s letter worked and Obama Sr. was offered a scholarship (from Tom Mboya in Kenya) to pursue a doctorate at Harvard.

Can that statement be confirmed? Sounds like an opinion to me, and flies in the face of the Percy Sutton assertion:

yes it is (BTW, link worked a 2nd time for me)

~~~~~

On his way east, Obama stopped in San Francisco and went to dinner at the Blue Fox in the financial district with Hal Abercrombie, who had moved to the city with his wife, Shirley. Abercrombie would never forget that dinner; he thought it showed the worst side of his old friend, a combination of anger and arrogance that frightened him. Shirley was a blonde with a high bouffant hairdo, and when she showed up at the side of Hal and Barack, the maitre d’ took them to the most obscure table in the restaurant. Obama interpreted this as a racial slight. When the waiter arrived, Obama tore into him, shouting that he was an important person on his way to Harvard and would not tolerate such treatment, Abercrombie recalled. “He was berating the guy and condescending every time the waiter came to our table. There was a superiority and an arrogance about it that I didn’t like.”

In the family lore, Obama was accepted into graduate school at the New School in New York and at Harvard, and if he had chosen the New School there would have been enough scholarship money for his wife and son to come along. However, the story goes, he opted for Harvard because of the world-class academic credentials a Crimson degree would bring. But there is an unresolved part of the story: Did Ann try to follow him to Cambridge? Her friends from Mercer Island were left with that impression. Susan Botkin, Maxine Box and John W. Hunt all remember Ann showing up in Seattle late that summer with little Barry, as her son was called.

“She was on her way from her mother’s house to Boston to be with her husband,” Botkin recalled. “[She said] he had transferred to grad school and she was going to join him. And I was intrigued with who she was and what she was doing. Stanley was an intense person . . . but I remember that afternoon, sitting in my mother’s living room, drinking iced tea and eating sugar cookies. She had her baby and was talking about her husband, and what life held in store for her. She seemed so confident and self-assured and relaxed. She was leaving the next day to fly on to Boston.”

But as Botkin and others later remembered it, something happened in Cambridge, and Stanley Ann returned to Seattle. They saw her a few more times, and they thought she even tried to enroll in classes at the University of Washington, before she packed up and returned to Hawaii.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/08/22/AR2008082201679_5.html

thanks for posting that excerpt, I couldn’t help myself, I burst out laughing! I’ll read it again and reply when I’ve settled down, LOL!

Fred here is the article:

Though Obama Had to Leave to Find Himself, It Is Hawaii That Made His Rise Possible

Before the end of her first semester, Ann learned she was pregnant. The jolt that most parents might feel at such news from a teenage daughter was intensified for the Dunhams by the fact that the father was Obama. Madelyn Dunham has steadfastly declined requests for interviews this year, but a few years ago she talked to the Chicago Tribune's David Mendell, who was researching his biography, "Obama: From Promise to Power." Dunham, known for her practicality and skepticism in a family of dreamers, told Mendell that Stanley Ann had always been stubborn and nonconformist, and often did startling things, but none were more stubborn or surprising than her relationship with Obama.

When Mendell pressed her about Obama, she said she did not trust the stories the Kenyan told. Prodding further, the interviewer noted that Obama had "a great deal of charm" and that his father had been a medicine man. "She raised her eyebrows and nodded to herself," Mendell wrote of Madelyn. " 'He was . . .' she said with a long pause, 'strange.' She lingered on the a to emphasize 'straaaaaange.' "

On Feb. 2, 1961, against Madelyn's hopes, and against the desires of Obama's father back in Kenya, Ann and Obama hopped a plane to Maui and got married. No guests, not even family members, were there. Barack Hussein Obama Jr. was born six months later in Honolulu.

Ann, the earnest student, dropped out of school to take care of him. Her husband finished his degree, graduating in June 1962, after three years in Hawaii, as a Phi Beta Kappa straight-A student. Then, before the month was out, he took off, leaving behind his still-teenage wife and namesake child. He did not return for 10 years, and then only briefly. A story in the Star-Bulletin on the day he left, June 22, said Obama planned a several-weeks grand tour of mainland universities before he arrived at Harvard to study economics on a graduate faculty fellowship. The story did not mention that he had a wife and an infant son.

Many years later, Barack Jr., then in high school, found a clipping of the article in a family stash of birth certificates and old vaccination forms. Why wasn't his name there, or his mother's? He wondered, he later wrote, "whether the omission caused a fight between my parents."

On his way east, Obama stopped in San Francisco and went to dinner at the Blue Fox in the financial district with Hal Abercrombie, who had moved to the city with his wife, Shirley. Abercrombie would never forget that dinner; he thought it showed the worst side of his old friend, a combination of anger and arrogance that frightened him. Shirley was a blonde with a high bouffant hairdo, and when she showed up at the side of Hal and Barack, the maitre d' took them to the most obscure table in the restaurant. Obama interpreted this as a racial slight. When the waiter arrived, Obama tore into him, shouting that he was an important person on his way to Harvard and would not tolerate such treatment, Abercrombie recalled. "He was berating the guy and condescending every time the waiter came to our table. There was a superiority and an arrogance about it that I didn't like."

In the family lore, Obama was accepted into graduate school at the New School in New York and at Harvard, and if he had chosen the New School there would have been enough scholarship money for his wife and son to come along. However, the story goes, he opted for Harvard because of the world-class academic credentials a Crimson degree would bring. But there is an unresolved part of the story: Did Ann try to follow him to Cambridge? Her friends from Mercer Island were left with that impression. Susan Botkin, Maxine Box and John W. Hunt all remember Ann showing up in Seattle late that summer with little Barry, as her son was called.

"She was on her way from her mother's house to Boston to be with her husband," Botkin recalled. "[She said] he had transferred to grad school and she was going to join him. And I was intrigued with who she was and what she was doing. Stanley was an intense person . . . but I remember that afternoon, sitting in my mother's living room, drinking iced tea and eating sugar cookies. She had her baby and was talking about her husband, and what life held in store for her. She seemed so confident and self-assured and relaxed. She was leaving the next day to fly on to Boston."

But as Botkin and others later remembered it, something happened in Cambridge, and Stanley Ann returned to Seattle. They saw her a few more times, and they thought she even tried to enroll in classes at the University of Washington, before she packed up and returned to Hawaii.

* * *

By the time he was 6, Barry Obama was a hyper-aware boy with much to think about. His mother had returned to school at the University of Hawaii and had received a degree in what her family considered an unlikely major -- math. She had divorced Barack Obama Sr., who had finished his graduate work at Harvard and was back in Kenya, now living with a third woman. Ann had moved on and was soon to wed another international student, Lolo Soetoro, and follow him back to his home country, Indonesia, bringing Barry along. Her brief first marriage was in the past, Seattle in the remote distance, and Kansas farther still.

It was at this point that Barry developed a way of looking at his mother that essentially would last until her death three decades later. His take on her -- both the ways he wanted to be like her and how he reacted against her -- shaped him permanently and is central to understanding his political persona today, the contrast of an embracing, inclusive sensibility accompanied by an inner toughness and wariness. Starting at an early age, he noticed how his mother was curious and open, eager to find the best in people and situations, intent on softening the edges of the difficult world for her hapa son. There were many times when this made him think that she was naive, sometimes heartbreakingly so, and that he had to be the realist in the family. To some degree, especially as he tried to explain himself later in "Dreams From My Father," he seemed to use his mother as a foil, setting her up as the quintessential well-intentioned white liberal idealist as a contrast to his own coming of age as a modern black man.

Whether this perception reflected objective reality is open to question. In her dealings later as a community worker and anthropologist in Indonesia and around the world, Ann showed a keen appreciation of the power structure and how to work with it or around it, and her doctoral thesis and other writings reveal a complex understanding of people and their motivations, free of dreamy idealism and wishful thinking. But she certainly tried to present the world in the most hopeful, unthreatening light to her children, first Barry and then his little sister, Maya, the daughter she bore with Soetoro.

As Maya explained recently, looking back on the way she and her brother were raised: "[She wanted to] make sure that nothing ever became acrimonious and that everything was pretty and everything was sacred and everything was properly maintained and respected -- all the cultural artifacts and ways of being and living and thinking. We didn't need to make choices. We didn't need to discard anything. We could just have it all and keep it all. It was this sense of bounty and beauty."

The son's notion of his loving mother's naivete began in Indonesia, when they arrived in the capital city, Jakarta, in 1967, joining Soetoro, who had returned to his home country several months earlier. The place was a fantasia of the unfamiliar and grotesque to young Barry, with the exotic scent of danger. Monkeys, chickens and even crocodiles in the back yard. A land of floods, exorcisms, cockfights. Lolo was off working for Union Oil, Ann taught English at the U.S. Embassy, and Barry was overwhelmed in this strange new world. He recalled those days in his memoir with more acuity than he possibly could have had as a 6-year-old, but the words reflect his perceptions nonetheless.

His mother taught him history, math, reading and social studies, waking him at 4 each morning to give him special tutoring, pouring her knowledge into his agile brain. But it was left to his stepfather to orient him in the cruel ways of the world. Soetoro taught him how to fight and defend himself, how not to give money to beggars, how to deal strictly with servants, how to interact with the world on its own unforgiving terms, not defining everything as good or bad but merely as it is. " 'Your mother has a soft heart,' he told me after she tried to take the blame for knocking a radio off the dresser," Obama quoted Soetoro in his memoir. " 'That's good in a woman, but you will be a man someday, and a man needs to have more sense.' " Men, Soetoro explained, take advantage of weakness in other men. " 'They're like countries that way.' "

All of this, as Obama later interpreted it, related to the exercise of power, hidden and real. It was power that forced Soetoro to return to Indonesia in the first place. He had been summoned back to his country from Hawaii in 1966 and sent to work in New Guinea for a year because the ruling regime, after a widespread, bloody purge of communists and leftists, was leery of students who had gone abroad and wanted them back and under control. To his mother, power was ugly, Obama determined: "It fixed in her mind like a curse." But to his stepfather, power was reality -- and he "made his peace" with it.

Which response to the world had a deeper effect on the person Barry Obama would become? Without doubt it was his mother's. Soetoro, described later by his daughter Maya as a sweet and quiet man, resigned himself to his situation and did not grow or change. He became a nondescript oilman, befriending slick operators from Texas and Louisiana who probably regarded him with racial condescension. He went to their parties and played golf at the country club and became western and anonymous, slipping as far away as possible from the dangers of the purge and the freedom of his student days.

Ann certainly had more options, but the one she eventually chose was unusual. She decided to deepen her connection to this alien land and to confront power in her own way, by devoting herself to understanding the people at the core of Indonesian culture, artisans and craftsmen, and working to help them survive.

Here was an early paradox that helped shape Obama's life, one he would confront again and again as he matured and remade himself: A certain strain of realism can lead to inaction. A certain form of naivete can lead to action.

By the time Maya was born in 1970, Ann's second marriage was coming apart. This time, there was no sudden and jarring disappearance. The relationship lingered off and on for another 10 years, and Lolo remained part of Maya's life in a way that Barack Obama did not for Barry.

As Maya analyzed her parents' relationship decades later, she concluded that she came along just as her mother was starting to find herself. "She started feeling competent, perhaps. She acquired numerous languages after that. Not just Indonesian, but her professional language and her feminist language. And I think she really got a voice. So it's perfectly natural that she started to demand more of those who were near her, including my father. And suddenly his sweetness wasn't enough to satisfy her needs."

* * *

"Dreams From My Father" is as imprecise as it is insightful about Obama's early life. Obama offers unusually perceptive and subtle observations of himself and the people around him. Yet, as he readily acknowledged, he rearranged the chronology for his literary purposes and presented a cast of characters made up of composites and pseudonyms. This was to protect people's privacy, he said. Only a select few were not granted that protection, for the obvious reason that he could not blur their identities -- his relatives. And so it is that of all the people in the book, the one who takes it on the chin the most is his maternal grandfather, Stan Dunham.

It is obvious from the memoir, and from interviews with many people who knew the family in Hawaii, that Dunham loved his grandson and did everything he could to support him physically and emotionally. But in the memoir, Gramps comes straight out of the plays of Arthur Miller or Eugene O'Neill, a once-proud soul lost in self-delusion, struggling against the days.

When Barry was 10, his mother made the difficult decision to send him back to Honolulu to live with her parents so he could get better schooling. He had been accepted into the prestigious Punahou School, and Madelyn and Stan had moved from a large house on Kamehameha Avenue to the apartment on Beretania, only five blocks from the campus.

Gramps now seemed as colorful and odd as those monkeys in the back yard in Jakarta. He cleaned his teeth with the red cellophane string from his cigarette packs. He told off-color jokes to waitresses. A copy of Dale Carnegie's "How to Win Friends and Influence People" was always near at hand -- and only those who lived with him knew the vast distance between his public bonhomie and his private despair. The most powerful scene in the memoir, as devastating as it is lovingly rendered, described how Stan, by then out of the furniture business and trying his hand as a John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance salesman, prepared on Sunday night for the week ahead.

"Sometimes I would tiptoe into the kitchen for a soda, and I could hear the desperation creeping out of his voice, the stretch of silence that followed when the people on the other end explained why Thursday wasn't good and Tuesday not much better, and then Gramps's heavy sigh after he had hung up the phone, his hands fumbling through the files in his lap like those of a card player who's deep in the hole."

By the time Barry returned to Hawaii, Toot had become the stable financial source in the family, well known in the local lending community. In the library of the Honolulu Advertiser, no clippings mention Stan Dunham, but Madelyn Dunham crops up frequently in the business pages. A few months before Barry arrived from Indonesia, his grandmother had been promoted to vice president at the Bank of Hawaii along with Dorothy K. Yamamoto -- the first two female vice presidents in the bank's history.

It was during Barry's first year at Punahou School that his long-lost father stepped briefly into his life, and just as quickly disappeared again. He came for the month of December, and his mother returned from Indonesia beforehand to prepare Barry for the visit. She taught him more about Kenya and stories of the Luo people, but all of that knowledge dissolved at the first sight of the old man. He seemed far skinnier than Barry had imagined him, and more fragile, with his spectacles and blue blazer and ascot and yellowish eyes.

It was not an easy month, and what stuck in the boy's memory were the basketball that his dad gave him as a present and two dramatic events: when his father ordered him, in front of his mother and grandparents, to turn off the TV and study instead of watching "How the Grinch Stole Christmas," and when his father came to Miss Mabel Hefty's fifth-grade class at Punahou's Castle Hall to talk about Kenya. The first moment angered Barry; the second made him proud. But nothing much lingered after his father was gone.

That visit to Honolulu was bracketed by two trips that Obama's old snack bar friends from the University of Hawaii made to see him in Kenya. Late in 1968, Neil Abercrombie and Pake Zane traveled through Nairobi on a year-long backpacking trip around the world and stayed with Obama for several days before they made their way on to the port city of Mombasa and to India. No mention was made of Ann or the boy, but it was clear to Abercrombie that his old friend's life was not turning out as he had planned. "He seemed very frustrated, and his worst fears in his mind were coming true -- that he was being underutilized," Abercrombie said. "Everybody's virtue is his vice, and his brilliance and his assertiveness was obviously working against him as well."

Five years later, in 1973, Zane returned during another trip around the world.

"This time when I met Barack [Bear-ick, he said], he was a shell of what he was prior to that," Zane recalled. "Even from what he was in 1968. . . . He was drinking very heavily, and he was very depressed and as you might imagine had an amount of rage. He felt totally vulnerable."

Meanwhile, Barry's circumstances had changed somewhat. His mother, separated from Lolo, was back in Hawaii with little Maya. Barry joined them in an apartment at Poki and Wilder, even closer to Punahou School. Ann was now fully engaged in the artisan culture of Indonesia and was beginning her master's degree work in anthropology. They had no money beyond her graduate school grants.

Maya's earliest memories go back to those years. Thirty-five years later, she can remember a filing cabinet and a rocking chair, and how she and her big brother would sit in the chair and keep rocking harder until it flipped over, which is what they wanted it to do. There was a television across from the rocker, and she would purposely stand in front of it during basketball games to irritate him. There were picnics at Puu Ualakaa State Park with Kentucky Fried Chicken and Madelyn's homemade baked beans and coleslaw and potato salad with the skins still on. And there was Big Sandwich Night, when Gramps would haul out all the meats and cheeses and vegetables.

After three years in Hawaii, Ann had to go back to Indonesia to conduct her fieldwork. Barry had absolutely no interest in returning to that strange place, so he stayed behind with his grandparents.

* * *

Keith and Tony Peterson were rummaging through the discount bin at a bookstore in Boulder, Colo., one afternoon and came across a copy of "Dreams From My Father" several years after it was first published. "We've got to buy this," Keith said to his brother. "Look who wrote it." Barry Obama. Their friend from Punahou School. They both bought copies and raced through the memoir, absorbed by the story and especially by the sections on their high school years. They did not recognize any of the names, since they were all pseudonyms, but they recognized the smells and sounds and sensibility of the chapters and the feelings Obama expressed as he came of age as a black teenager.

This was their story, too. They wondered why Obama focused so much on a friend he called Ray, who in fact was Keith Kukagawa. Kukagawa was black and Japanese, and the Petersons did not even think of him as black. Yet in the book, Obama used him as the voice of black anger and angst, the provocateur of hip, vulgar, get-real dialogues.

But what interested the Petersons more was Obama's interior dialogue with himself, his sense of dislocation at the private school, a feeling that no matter what he did, he was defined and confined by the expectations and definitions of white people. Keith Peterson had felt the same way, without being fully able to articulate his unease. "Now keep in mind I am reading this before [Obama] came on the national scene," he said later. "So I am reading this still person to person, not person to candidate, and it meant a lot more for that reason. It was a connection. It was amazing as I read this book, so many decades later, at last I was feeling a certain amount of closure, having felt so isolated for so long. I wasn't alone. I spent a good portion of my life thinking I had experienced something few others had. It was surprisingly satisfying to know I wasn't crazy. I was not the only one struggling with some of these issues."

But his brother Tony, who reached Punahou first, said he had regular discussions with Obama about many issues, including race. Tony was a senior when Obama was a freshman. The Petersons lived miles away, out in Pearl City, having grown up in a military family that was first based at Schofield Barracks. While Obama walked only five blocks to school, Tony had to ride city buses for an hour and a half each morning to get there.

As he remembered it, he was one of a handful of black students at Punahou then, a group that included Obama, Lewis Anthony, Rik Smith and Angie Jones. Peterson, Smith and Obama would meet on the steps outside Cooke Hall for what, with tongue in cheek, they called the Ethnic Corner. Obama and Smith were biracial, one black and white, the other black and Indian. Both of Peterson's parents were black, but he felt uneasy because he was an academically inclined young man whom people thought "sounded white."

"Barry had no personal reference for his blackness. All three of us were dealing with it in different ways," Peterson recalled. "How do we explore these things? That is one thing we talked about. We talked about time. We talked about our classes. We talked about girls. We talked specifically about whether girls would date us because we were black. We talked about social issues. . . . But our little chats were not agonizing. They were just sort of fun. We were helping each other find out who we were. We talked about what we were going to be. I was going to be a lawyer. Rick was going to be a lawyer. And Barry was going to be a basketball player."

Obama's interest in basketball had come a long way since his absent father showed up and gave him his first ball. Now it was his obsession. He was always dribbling, always playing, either on the outdoor courts at Punahou or down at the playground on King Street across from the Baskin-Robbins where he worked part-time. He was a flashy passer with good moves to the basket but an uneven and unorthodox jump shot, pulling the ball back behind his head so far that it almost disappeared behind him. Basketball dominated his time so much that his mother worried about him. In ninth grade, at least, he was the naive one, believing he could make a life in the game.

In Tony Peterson's senior yearbook, Obama wrote: "Tony, man, I sure am glad I got to know you before you left. All those Ethnic Corner trips to the snack bar and playing ball made the year a lot more enjoyable, even though the snack bar trips cost me a fortune. Anyway, great knowing you and I hope we keep in touch. Good luck in everything you do, and get that law degree. Some day when I am a pro basketballer, and I want to sue my team for more money, I'll call on you."

Barry's mother, who had a wry sense of humor, once joked to friends that she was a pale-skinned Kansan who married a Kenyan and an Indonesian so she could have brown children who would not have to worry about sunburn. Her understanding of race was far deeper than that joke; she was always sensitive to issues of identity and made a point of inculcating her children in the cultures of their fathers. Still, there were some problems she could not resolve for them. Maya later said that her mother's overriding desire that her children not suffer perhaps got in the way.

"She didn't want us to suffer with respect to identity. She wanted us to think of it as a gift that we were multilayered and multidimensional and multiracial. This meant that she was perhaps unprepared when we did struggle with issues of identity. She was not really able to help us grapple with that in any nuanced way. Maybe it would make her feel like she hadn't succeeded in surrounding us with enough love. I remember Mom wanting it not to be an issue."

In an apparent effort to show a lifelong plot to power, some opponents last year pushed a story about Obama in which he predicted in kindergarten that one day he would be president. The conspiracy certainly seemed to go off the rails by the time he reached high school. Unlike Bill Clinton, who was the most political animal at Hot Springs High in Arkansas -- organizing the marching band as though it was his own political machine, giving speeches at the local Rotary, maneuvering his way into a Senate seat at the American Legion-sponsored Boys Nation -- Obama stayed away from student leadership roles at Punahou and gave his friends no clues that a few decades later he would emerge as a national political figure.

"When I look back, one of the things that stood out was that he didn't stand out," said Keith Peterson, who was a year younger than Obama. "There was absolutely nothing that made me think this is the road he would take." His friends remember him as being kind and protective, a prolific reader, keenly aware of the world around him, able to talk about foreign affairs in a way that none of the rest of them could, and yet they did not think of him as politically or academically ambitious. In a school of high achievers, he coasted as a B student. He dabbled a little in the arts, singing in the chorus for a few years and writing poetry for the literary magazine, Ka Wai Ola.

The group he ran with was white, black, brown and not identified with any of the traditional social sets at the school: the rich girls from the Outrigger Canoe Club, the football players, the math guys, the drama crew, the volleyball guys. Among Obama's friends, "there were some basketball players in there, but it was kind of eclectic," recalled Mike Ramos, also a hapa, his mother Anglo and his father Filipino. "Was there a leader? Did we defer to Barry? I don't think so. It was a very egalitarian kind of thing, also come as you are."

They body-surfed at Sandy Beach Park on the south shore, played basketball day and night, went camping in the hills above the school, sneaked into parties at the university and out at Schofield Barracks, and listened to Stevie Wonder, Fleetwood Mac, Miles Davis and Grover Washington at Greg and Mike Ramos's place across from the school or in Barry's room at his grandparents' apartment. ("You listen to Grover? I listen to Grover," Mike Ramos still remembers Barry saying as a means of introducing himself during a conversation at a party.)

And they smoked dope. Obama's drug use is right there in the memoir, with no attempt to make him look better than he was. He acknowledged smoking marijuana and using cocaine but said he stopped short of heroin. Some have suggested that he exaggerated his drug use in the book to hype the idea that he was on the brink of becoming a junkie; dysfunction and dissolution always sell in memoirs.

But his friends quickly dismissed that notion. "I wouldn't call it an exaggeration," Greg Ramos said. Keith Peterson said: "Did I ever party with Barack? Yes, I did. Do I remember specifically? If I did, then I didn't party with him. Part of the nature of getting high is you don't remember it 30 minutes later. Punahou was a wealthy school with a lot of kids with disposable income. The drinking age in Hawaii then was 18, so a lot of seniors could buy it legally, which means the parent dynamic was not big. And the other partying materials were prevalent, being in Hawaii. There was a lot of partying that went on. And Barack has been very open about that. Coming from Hawaii, that would have been so easy to expose. If he hadn't written about it, it would have been a disaster."

If basketball was Obama's obsession during those years, it also served as a means for him to work out some of his frustrations about race. In the book and elsewhere, he has emphasized that he played a "black" brand of ball, freelancing his way on the court, looking to drive to the hoop rather than wait around for a pick and an open shot. His signature move was a double-pump in the lane. This did not serve him well on the Punahou varsity team. His coach, Chris McLachlin, was a stickler for precisely where each player was supposed to be on the court and once at practice ordered his team to pass the ball at least five times before anyone took a shot. This was not Obama's style, and he had several disagreements with the coach. He never won the arguments, and the team did well enough anyway. Adhering to McLachlin's deliberate offense, the Buffanblu won the state championship, defeating Moanalua 60-28. Obama came off the bench to score two points. So much for the dream of becoming a rich NBA star.

His senior year, his mother was back home from Indonesia and concerned that her son had not sent in his college applications. In their tensest confrontation in the memoir, he eggs her on by saying it that was no big deal, that he might goof off and stay in Hawaii and go to school part-time, because life was just one big crapshoot anyway.

Ann exploded. She had rebelled herself once, at his very age, reacting against her own parents -- and perhaps against luck and fate -- by ignoring their advice and getting pregnant and marrying a man she did not know the way she thought she did. Now she was telling her son to shape up, that he could do anything he wanted if he put in the effort. "Remember what that's like? Effort? Damn it, Bar, you can't just sit around like some good-time Charlie, waiting for luck to see you through."

* * *

Sixteen years later, Barry was no more, replaced by Barack, who had not only left the island but had gone to two Ivy League schools, Columbia undergrad and Harvard Law, and written a book about his life. He was into his Chicago phase, reshaping himself for his political future, but now was drawn back to Hawaii to say goodbye to his mother. Too late, as it turned out. She died on Nov. 7, 1995, before he could get there.

Ann had returned to Honolulu early that year, a few months before "Dreams From My Father" was published. She was weakened from a cancer that had been misdiagnosed in Indonesia as indigestion. American doctors first thought it was ovarian cancer, but an examination at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York determined that it was uterine cancer that had spread to her ovaries. Stan had died a few years earlier, and Madelyn still lived in the apartment on Beretania. Ann took an apartment on the same floor, and underwent chemotherapy treatments while keeping up with her work as best she could. "She took it in stride," said Alice Dewey, chair of the University of Hawaii anthropology department, where Ann did her doctoral dissertation. "She never complained. Never said, 'Why me?' "

Ann's career had reached full bloom. Her dissertation, published in 1992, was a masterwork of anthropological insight, delineating in 1,000 pages the intricate world of peasant metalworking industries in Indonesia, especially traditional blacksmithing, tracing the evolution of the crafts from Dutch colonialism through the regime of General Suharto, the Indonesian military strongman. Her deepest work was done in Kajar, a blacksmithing village near Yogyakarta. In clear, precise language, she described the geography, sociology, architecture, agriculture, diet, class structure, politics, business and craftsmanship of the village, rendering an arcane subject in vivid, human terms.

It was a long time coming, the product of work that had begun in 1979, but Dewey said it was worth the wait: Each chapter as she turned it in was a polished jewel.

Her anthropology in Indonesia was only part of Ann's focus. She had also worked in Lahore, Pakistan; New Delhi; and New York, helping to develop microfinancing networks that provided credit to female artisans in rural communities around the world. This was something she had begun in Jakarta for the Ford Foundation in the early 1980s, when she helped refine Bank Rakyat, set up to provide loans to farmers and other rural entrepreneurs in textiles and metalwork, the fields she knew best. David McCauley, who worked with her then, said she had earned a worldwide reputation in the development community. She had a global perspective from the ground up, he said, and she passed it along to her children, Barack and Maya.

Maya was in New York, about to start graduate school at New York University, when her mother got sick. She and her brother were equally slow to realize that the disease was advancing so rapidly. Maya had seen Ann during that visit to Sloan-Kettering, and "she didn't look well. She was in a wheelchair . . . but I guess I thought that was the treatment. I knew that someday she would die, but it never occurred to me that it would be in November. I think children are capable of stretching out the boundaries of denial." School always came first with Ann, and she had urged Maya to stay at NYU until the December break.

But by November her condition had worsened. She was put on morphine to ease the pain and moved from her apartment to the Straub Clinic. One night she called Maya and said she was scared. "And my last words to her, where she was able to respond, were that I was coming. I arrived on the seventh. My grandmother was there and had been there for some time, so I sent her home and talked to Mom and touched her and hugged her, and she was not able to respond. I read her a story -- a book of Creole folk tales that I had with me about renewal and rebirth -- and I said it was okay with me if she decided to go ahead, that I couldn't really bear to see her like that. And she died. It was about 11 that night."

Barack came the next day. He had just finished a book about his missing father, but now it was more clear to him than ever that his mother had been the most significant force in shaping his life. Even when they were apart, she constantly wrote him letters, softly urging him to believe in himself and to see the best in everyone else.

A small memorial service was held in the Japanese Garden behind the East-West Center conference building on the University of Hawaii campus. Photographs from her life were mounted on a board: Stanley Ann in Kansas and Seattle, Ann in Hawaii and Indonesia. Barack and Maya "talked story," a Hawaiian phrase that means exactly what it sounds like, remembering their uncommon mother. They recalled her spirit, her exuberance and her generosity, a worldliness that was somehow very fresh and naive, maybe deliberately naive, sweet and unadulterated. And her deep laugh, her Midwestern sayings, the way she loved to collect batiks and wear vibrant colors and talk and talk and talk.

About 20 people made it to the service. When it was over, they formed a caravan and drove to the south shore, past Hanauma Bay, stopping just before they reached Sandy Beach, Barry's favorite old haunt for body surfing. They gathered at a lookout point with a parking lot, and down below, past the rail and at the water's edge, a stone outcropping jutting over the ocean in the shape of a massive ironing board. This was where Ann wanted them to toss her ashes. She felt connected to Hawaii, its geography, its sense of aloha, the fact that it made her two children possible -- but the woman who also loved to travel wanted her ashes to float across the ocean. Barack and Maya stood together, scattering the remains. The others tossed flower petals into the water.

Suddenly, a massive wave broke over the ironing board and engulfed them all. A sign at the parking lot had warned visitors of the dangers of being washed to sea. "But we felt steady," Maya said. "And it was this very slippery place, and the wave came out of nowhere, and it was as though she was saying goodbye."

Barack Obama left Hawaii soon after and returned to his Chicago life.

According to a letter on file in the Mboya papers at Stanford University's Hoover Institution, "most" of Obama Sr.'s early expenses in the United States were covered by an international literacy expert named Elizabeth Mooney Kirk, who had traveled widely in Kenya. Kirk wrote to Mboya in May 1962 to request additional funds to "sponsor Barack Obama for graduate study, preferably at Harvard." She said she would "like to do more" to assist the young man but had two stepchildren ready for college.

[What is confirmed is that this is what the Mboya papers state, but I have not found the additional info about a "scholoarship," per se]

Also FYI: Elizabeth Mooney married Mr.Elmer Kirk in 1960 per Mooney-Kirk's "My Adventures in Literacy Journalism" p 83.

wait??? are you confusing the 2 BHO’s? This about BHO, Jr:

Percy Sutton (Malcom X’s Lawyer) Says Barack Obama Knows And Was Financed By The Racist Radical Muslim And Saudi Advisor Dr. Khalid Al-Mansour

Yep, you’re right, I wasn’t concentrating! My very bad...however...it’s understandable, IMO the money for both came from the same source.

Think about it.

TOM MBOYA: THE UNTOLD STORY

EXCERPT:

...In many ways, with the death of Mboya, the nascent enterprise that was “project Kenya” – the building of a nation from what American writer Paul Theroux once called “the querulous republic”, an assortment of ethnic communities fiercely competing for control of the centre – began to crumble.

The sense of optimism that had come with independence and somehow survived the ideological discord within KANU, was extinguished with the assassination of Tom Mboya on that Saturday afternoon. Nairobi, and Kenya as a whole, became a nation of silences, suspicions and secrets.

The tenuous ideas of solidarity and nation building disintegrated.

The uhuru nationalist project, not six years old, was effectively taken over by the forces of tribalism and ethnic patronage.

Only Mboya, whose personal and public life had transcended beyond the preoccupations of ethnic chauvinism and parochialism, had possessed the imagination to lead the country in a new direction.

Mahathir Mohamed, the Malaysian Prime Minister and architect of that country’s post-colonial renaissance, was later to comment: “when you killed Tom, you lost 30 years”.

1969 was in many ways a watershed year.

Rumours in late 1968 that President Kenyatta had suffered a heart attack brought home to the nation but especially to the close circle around Kenyatta –known as the Kiambu Mafia – that the founding President was not immortal.

The politics of succession, which would become the enduring theme of Kenyan politics, began to play out in earnest.

Having neutralised the left wing of KANU in the mid-60s, first with the assassination of Pinto in 1965 and then the sidelining of Jaramogi Odinga at the Limuru Conference in `66, Mboya, the obvious successor to Kenyatta, himself became a target for neutralisation by the Kiambu Mafia.

There had been an attempt on his life in early 1969.

By the middle of that year, Mboya found himself increasingly isolated on the domestic political scene.

Internationally, the assassination of Robert Kennedy, an intimate friend and perhaps his biggest champion in the United States, was a big blow to Mboya.

With the British already quite nervous of his strong links with the United States, the jostling around the Kenya presidency acquired added urgency, and rendered Mboya increasingly more vulnerable.

There were, in short, many reasons and many people who wanted Tom Mboya dead...

http://africanewsonline.blogspot.com/2009/07/tom-mboya-untold-story.html

Dr Maya Angelou with Malcolm X in Ghana, 1964.

Angelou left Ghana when her friend Malcolm X (El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz) asked her to join him in New York and help him create an Organization of African-American Unity. As soon as she arrived, she phoned him to tell him that she would first spend time with her family in California. Within 48 hours came the devastating news of Malcolm's assassination. With the help of her wise mother, her beloved brother and her loyal sister-friends, she picked herself up and found work: singing in a Hawaii nightclub and doing market research in Watts, the black area of Los Angeles. In 1965 she watched, deliberately courting arrest, as the area erupted into violent riots.

GHANA 1964

We Need a Mau Mau in Mississippi

On December 20, 1964 at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem, Malcolm X declared, “Oginga Odinga [the Vice President of recently-liberated Kenya] is not passive. He’s not meek. He’s not humble. He’s not nonviolent. But he’s free.”

This fact was part of a larger object lesson that Malcolm X had for Black Americans:

‘...Jomo Kenyatta, Oginga Odinga, and the Mau Mau will go down as the greatest African patriots and freedom fighters that that continent ever knew, and they will be given credit for bringing about the independence of many of the existing independent states on that continent right now. There was a time when their image was negative, but today they’re looked upon with respect and their chief is the president and their next chief is the vice president.

‘I have to take time to mention that because, in my opinion, not only in Mississippi and Alabama, but right here in New York City, you and I can best learn how to get real freedom by studying how Kenyatta brought it to his people in Kenya, and how Odinga helped him, and the excellent job that was done by the Mau Mau freedom fighters. In fact, that’s what we need in Mississippi. In Mississippi we need a Mau Mau. In Alabama we need a Mau Mau. In Georgia we need a Mau Mau. Right here in Harlem, in New York City, we need a Mau Mau.

‘I say it with no anger; I say it with very careful forethought...’

http://georgehartley.blogspot.com/2009/01/we-need-mau-mau-in-mississippi-malcolm.html

William Ayres office door...

PURELY SPECULATIVE:

Barack Obama's Close Encounter with the Weather Underground

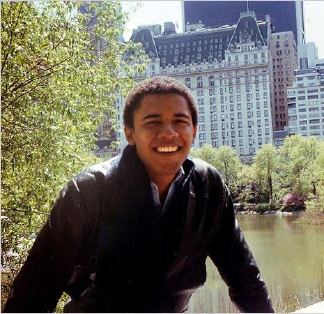

Barack Obama in New York ca. 1981 or '82.

Excerpt:

...Mr. Obama explained that he had taken the train out from Chicago to visit the Ayers’ in order to thank them for their help with his “education.” At this time, Mr. Obama had recently graduated from Columbia and would soon enter Harvard Law School. Hulton and Obama “spoke for a few minutes, first chatting about the Ayers family,” Hulton said. Hulton said he did not learn whether the help Obama received from the Ayers’ was financial or in some other form.

Hulton agreed that it was an exceptional event to encounter a black man on his route and that Obama may have felt it prudent to introduce himself to the letter carrier before approaching the Ayers house. Hulton usually delivered mail on Montclair at mid-day, “sometimes as early as 11:30 in the morning or as late as 12:30 or 1:00 PM.”

Hulton says he recalls when the very first black family moved into the upper middle class white suburb in the 1960s. Hulton says at the time, after he had come out of military service, he was a supporter of Martin Luther King who had pressed for fair housing in the Chicago area. “I took some flak about my support for civil rights from my fellow workers at the time,” he said.

Mr. Hulton recalls that he probably asked what Mr. Obama was studying in school and at one point Mr. Obama said that he intended to become President of the United States. Mr. Hulton said he was “taken aback” by the statement but recalls that he did not think Mr. Obama was “arrogant, but just self assured and a person with a lot of self confidence.” “It was not said with hubris,” Hulton recalled, “but with an air of self-assuredness.”

“I told him there was no reason why he couldn’t become president,” Hulton recalled. Obama was dressed “nicely but casually, a slacks and shirt, not jeans and a t-shirt, but definitely not a coat or tie,” he said. After the brief conversation Hulton continued on his route and did not turn back to see whether the Ayers’ were at home or whether Obama entered their house...

Stephen Diamond 09.27.09 at 1:52 pm Hulton said Obama looked 19 but is certain their meeting took place in the mid-1980s and thus placed his age as early 20s.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.