|

|

From the National Geographic Website.....

"It was a hungry time in Charleston, South Carolina, those early months of 1864. Bombarded by land and blockaded by sea, the city that cheered the opening shots of the American Civil War remained proudly defiant, but its Rebel defenders were looking mighty pinched. Salt pork, corn, boots, blankets, lead for musket balls, and most everything else the army needed was in critically short supply. The Union Navy's chokehold on the city's harbor would have to be broken soon, and the best hope for doing that lay with a strange and secret new weapon—a "diving torpedo-boat" christened the H. L. Hunley.

Shortly after sunset on the night of February 17, at a dock on nearby Sullivans Island, eight audacious Confederates squeezed inside the claustrophobic iron vessel and set out on a quixotic mission. Affixed to the boat's bow was a spar tipped with a deadly charge of black powder. At the helm was Lt. George Dixon, a bold-hearted, battle-scarred army officer. Behind him, wedged shoulder to shoulder on a wooden bench, sat seven crewmen whose muscles powered the sub's hand-cranked propeller. As the crew began turning the heavy iron crankshaft, Dixon consulted a compass and set course for a daunting target—the steam sloop U.S.S. Housatonic, stationed four miles (six kilometers) offshore. The Rebels' plan was to run about six feet (two meters) below the surface until they neared the blockader. But in order for Dixon to take final aim, he would have to resurface just enough to peer through the sub's tiny forward viewport.

At 8:45 p.m. John Crosby, acting master aboard the Housatonic, spotted something off the starboard beam that looked at first like a "porpoise, coming to the surface to blow." There had been warnings of a possible attack by a Confederate "infernal machine," and Crosby was swift to sound the alarm. Sailors rushed to quarters and let loose a barrage of small arms fire at the alien object barely breaking the surface, but the attacker was unstoppable.

Two minutes later the Hunley rammed her spar into the Housatonic's starboard side, well below the waterline. As the sub backed away, a trigger cord detonated the torpedo, blowing off the entire aft quarter of the ship. It was an epic moment."....Glenn Oeland

From the Friends of the Hunley Website.....

The explosion caused the USS Housatonic to burn for three minutes before sending the sloop-of-war collapsing to the bottom killing five sailors.

The Hunley then surfaced long enough for her crew to signal their comrades on the shore of Sullivan's Island with a blue magnesium light, indicating a successful mission. The shore crew stoked their signal fires and anxiously awaited the Hunley's safe return. But minutes after her historic achievement, the Hunley and all hands onboard vanished into the sea without a trace. That night history was made. At the same moment, a mystery was born. The Hunley became the first submarine ever to sink an enemy ship. But what caused her to sink to the bottom of the sea?

The world would have to wait until the tools of modern technology could begin to unlock the secrets of the Hunley. In 1995, author and adventurer Clive Cussler found the Hunley resting on the floor of the Atlantic Ocean. Intact and remarkably well preserved, the Hunley was found buried deep within the sand and silt just outside of Charleston Harbor. The recovery of the Hunley has turned out to be one of the most important single events in the history of South Carolina. After being lost at sea for 137 years, the Hunley was revealed on August 8, 2000, seen for the first time in her entirety, from bow to stern and top to bottom. It was indeed a remarkable moment in history.

South Carolina ETV provided live coverage

of the raising of the Hunley.

Click THIS LINK to view the event.

Gone to Glory

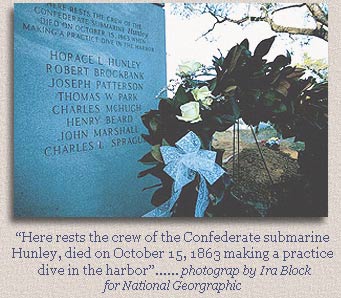

Called the “murdering machine” by some Confederate sailors, the Hunley inflicted more casualties on the South than on the North. Two crews, including this one captained by Horace Hunley and laid to rest near Charleston, died in accidents that occurred months before the sub’s final sinking. Yet to Lt. George Dixon, who captained the sub on her last mission, death was not too high a price to pay.

“Charleston and its defenders will occupy the most conspicuous place in the history of the war,” Dixon wrote a few weeks before he died at the Hunley’s helm, “and it shall be as much glory as I shall wish if I can inscribe myself as one of its defenders.”

Hunley Crew Burial Hunley Crew Burial

Lieutenant George E. Dixon

Arnold Becker

Corporal J. F. Carlsen

Frank Collins

Lumpkin

Miller

James A. Wicks

Joseph Ridgaway

April 17th, 2004

The morning was warm, and the waters off Charleston Harbor were unusually calm. It was perhaps the same sort of sea Hunley commander Lt. Dixon was waiting for in 1864 when he and his crew launched the experimental vessel that began the age of modern day submarines.

But this day would not mark the beginning of the Hunley crew's mission, but rather the completion of their century long journey to a final burial. On April 17th, 2004, the submarine pioneers that manned the first successful combat submarine were buried.

The ceremony began at 9.15 am with a memorial service at White Points Garden. Immediately after the ceremony, horse drawn caissons followed by a 19th century period dressed procession led the crew to the their final resting place. The procession marched 4.5-miles through downtown Charleston, and ended at Magnolia Cemetery. The Hunley's eight-man crew was then laid to rest next to others who lost their life on Hunley test missions.

When the Hunley was finally located in 1995, one of the main goals of the Hunley Commission and Friends of the Hunley was to bring these maritime pioneers home and lay them to rest with honor. The Hunley crew's burial required nearly a year of planning and volunteers gave thousands of hours of their time to ensure the crew's interment was a memorable and dignified event. Additionally, the Friends of Hunley research team was able to locate descendants of 3 of the crewmembers, and they participated in the burial of their ancestors.

State Senator Glenn F. McConnell, Chairman of the Hunley Commission said, in an open letter to all the funeral participants, "The funeral procession was magnificent and you all displayed the dignity that these brave heroes so richly deserved. I was so proud! Even the media remarked on the dignified and reverent manner with which all the ceremonies were completed. While it was both a celebratory and solemn occasion, everyone remembered that it was a funeral for maritime history makers and conducted themselves accordingly. This was indeed a fitting tribute. While the funeral may be over, memories will last forever as will my gratitude to all of you.

This was a day of unity for the Blue and the Gray; the North, South, East and West; all nationalities; and all faiths. It is my fervent hope that this bond will continue to grow and that we will all remain united in our efforts to preserve history."

A Time Capsule

The Hunley is now in the Warren Lasch Conservation Center. The conservation process has taken several years, but the excavation and analysis of the H.L. Hunley continues to provide many clues for archaeologists, conservators, anthropologists, and historians as they seek to understand the events that led to the loss of the H.L. Hunley and her crew, events that also led to the dawn of the modern era in submarine technology.

Reservations are required for the 20-minute tour where visitors can view the vessel, which rests at the Conservation Center in a tank of 50 degree fresh water, and hear a brief program on the submarine's history and historical significance.

|

|

|

|

![]() ((((((( dutchess )))))))

((((((( dutchess ))))))) ![]()