Posted on 05/16/2004 11:32:03 AM PDT by blam

Unearthing canyon's clues

Mysteries of Anasazi revealed in Chaco's centuries-old corn

By Jim Erickson, Rocky Mountain News

May 15, 2004

CHACO CANYON, N.M. - As Rich Friedman twists the handle of the T-shaped auger, the steel blades bite into loamy brown soil in a field where scientists suspect Anasazi farmers grew corn 1,000 years ago.

Friedman is part of a Boulder-led research team that collected 60 soil samples around the Chaco basin this month in an ongoing effort to determine where the Anasazi grew all the corn they would have needed to feed the thousands who periodically gathered in the canyon.

Advertisement

In a paper published last October in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the scientists matched the chemical fingerprint of seven ancient corn cobs found in Chaco's Pueblo Bonito to soils far from the canyon.

They concluded that the Anasazi, also known as the Ancestral Puebloans, hauled corn on their backs more than 50 miles to feed canyon dwellers.

That result is overturning the long-held belief that the Chacoans were agriculturally self-sufficient, growing everything they needed within the canyon through the clever use of captured and diverted surface runoff.

The findings also reinforce the view that Chaco was the ceremonial, administrative and economic center of a vast region spanning northwestern New Mexico's San Juan Basin.

"We continually underestimate the ability of these people to organize themselves on huge scales without the aid of modern technology," said University of Colorado archaeologist Linda Cordell, one of the authors of last fall's paper.

"That corn didn't just walk there all by itself," Cordell said. "People brought it there. That means they were organized on a regional scale that hasn't been seen in the San Juan Basin for hundreds and hundreds of years."

It now appears that during its heyday in the mid-1000s, Chaco Canyon was as dependent on outside supplies as an Antarctic base, said John Stein, an archaeologist with the Navajo Nation Historic Preservation Department.

Chaco was sustained by shipments of timber, pottery, stone and food carried in from the edges of the San Juan Basin. It also took in trade goods from Mexico, including copper bells, macaws and seashells from the Gulf of California.

Stein and the other corn project researchers are now expanding their investigation, which began three years ago. They're collecting new soil samples in and around Chaco Canyon, looking for likely Anasazi farming sites.

They plan to chemically analyze 20 to 40 more corn cobs collected by archaeologists decades ago inside the multistory sandstone "great houses" Chacoans built between A.D. 850 and 1150.

Then they'll try to match the cobs to sites throughout the arid, high-desert basin to determine where the corn was grown.

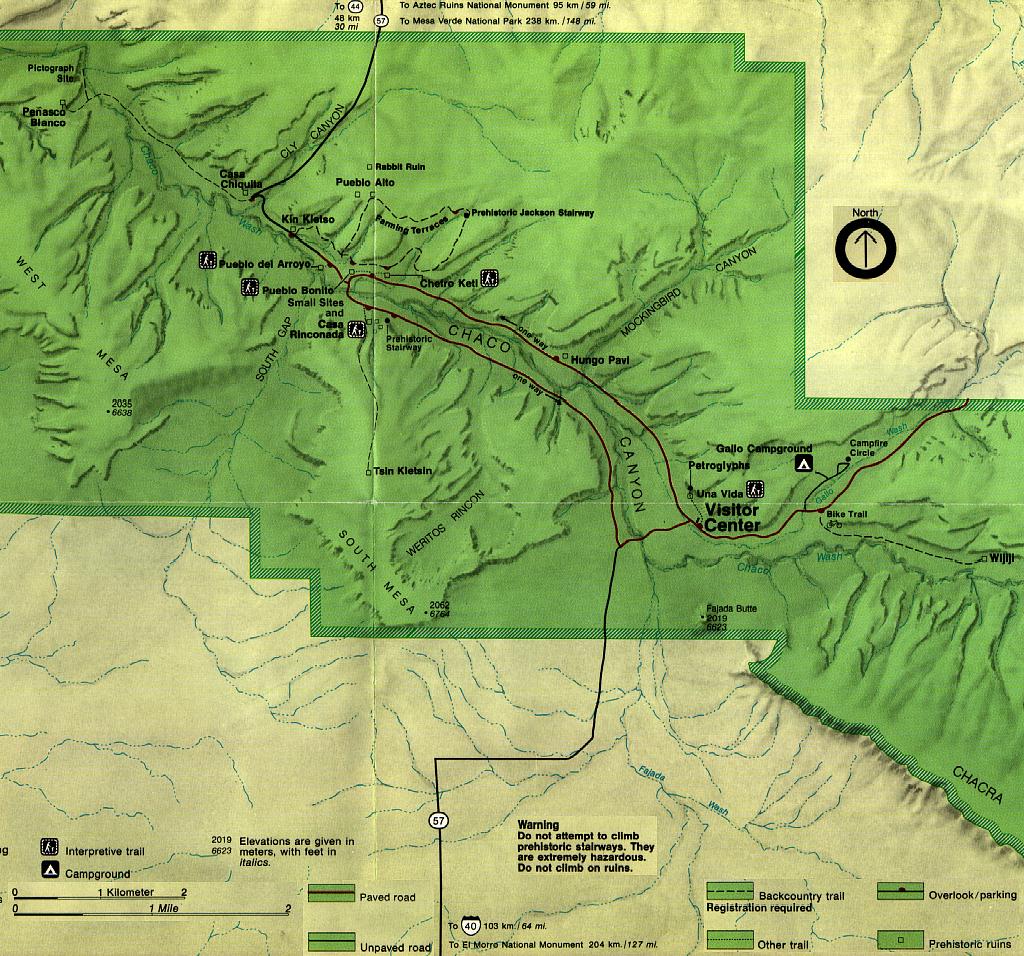

"A lot of ink has been spilled over the issue of farming in Chaco, but practically no systematic work has been done. We're trying to rectify that," Stein said recently, as the caravaning scientists pulled their pickups alongside Kin Kliz- hin, a great house seven miles southwest of the Chaco Culture National Historical Park visitor center.

The dark brown sandstone blocks of Kin Klizhin's 30-foot tower kiva loomed over the treeless landscape like a Scottish castle as the researchers traversed a flower-strewn field to collect bags of dirt for analysis back in a Boulder lab.

"It's been repeated over and over in textbooks that Chaco was some kind of breadbasket, and it's been held up as an example of making the desert bloom," Stein said.

"But this whole romantic idea that this was just a bunch of happy campers living in a utopia is not the case," he said.

"This place was a sorcerer's nest, an evil place," said Stein, whose views about Chaco reflect Navajo clan beliefs.

"And the soils here just suck pond water. It is patently obvious to me that they were not farming (all their corn) in Chaco Canyon," he said.

The Anasazi built 14 multistory great houses in Chaco Canyon. The structures averaged more than 200 rooms apiece and were up to four stories tall.

The largest and best-known site, Pueblo Bonito, held 700 rooms.

The purpose of the Chaco great houses has been debated for more than a century. One idea is that they were the sites of ritual feasts that pilgrims traveled from afar to attend.

During those events, Chaco Canyon's population may have swelled to 7,000 or more, Cordell said.

How did the Chacoans feed all those hungry mouths?

Paltry precipitation, a short growing season and unreliable flows in the Chaco Wash made canyon corn production precarious.

Even so, until the 1970s most archaeologists believed the Chacoans grew all their crops there, said Cordell, author of the textbook Archaeology of the Southwest, and director of the University of Colorado Museum.

That idea was supported by the findings of R. Gwinn Vivian, an Arizona archaeologist who uncovered an extensive system of dams, canals, ditches and walls used to channel Chaco runoff to farming terraces, garden plots and fields.

But in the 1970s, aerial photography and satellite images began to reveal the extent of the prehistoric road network that links Chaco Canyon to outlying communities across the San Juan Basin and beyond.

More than 400 miles of ancient roadways have been identified. They tie the core area around Pueblo Bonito to more than 150 other great houses in a region the size of West Virginia.

It became clear that the Chaco Canyon great houses were once the hub of the San Juan Basin. The roads were spokes connecting that hub to the outlying communities.

More recent studies have shown that the Anasazi used the roads to haul roof timbers to Chaco - without the help of draft animals or the wheel - from the base of the Chuska Mountains, 50 miles to the west. Clay pots and chert, a fine-grained rock used to make projectile points, also were imported from the area.

Cordell and others wondered if the same was done with corn.

She approached researchers at the U.S. Geological Survey in Boulder about three years ago. Geochemist Larry Benson suggested using isotopic ratios of the element strontium to trace ancient corn cobs to the soils where they were grown.

The researchers analyzed the chemical content of seven prehistoric corn cobs collected at Pueblo Bonito by archaeologist George Pepper between 1886 and 1899. The 3- to 5-inch cobs had been in storage at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Centuries ago, when the plants that produced those cobs grew, their roots took up strontium from the soil. The ratio of the various forms, or isotopes, of strontium in the cobs provides a chemical fingerprint that can be used to find their source soils, Benson said.

The researchers collected soil and water samples from likely agricultural sites in and around Chaco Canyon. The strontium ratios in the Pueblo Bonito cobs matched soils from the base of the Chuskas and from the San Juan and Animas river flood plains 56 miles to the north.

"I think it's extremely valuable information," said archaeologist Steve Lekson, curator of anthropology at the University of Colorado.

"Chert and obsidian and finished pots in bulk - hundreds of thousands of pots - were coming into Chaco. And we knew they were bringing in timbers from the Chuskas," said Lekson, who is not involved with the corn research.

"But this is the first time that we can prove it was happening with corn as well," he said. "It puts the nails in the coffin of self-sufficiency, and it opens the door to another idea."

That other idea is the notion that Chaco Canyon served as a "corn bank" that distributed maize throughout the San Juan Basin in the 1000s. Surplus corn was brought to the central hub from fields on the edges of the basin, then redistributed to struggling farmers in other areas, according to the model first proposed by archaeologist James Judge in 1976.

"There were episodes in the past when there were people out there who were calling the shots and organizing things at Chaco - political leaders who lived in nice houses," Lekson said.

"Maybe the great houses were warehouses, residences and administrative offices," said Lekson, author of The Chaco Meridian.

And who were those Chaco leaders, living in luxury and calling the shots?

According to some Navajo clan traditions, they included a ruthless ruler known as the Gambler, who gained control of people by defeating them in various games of chance.

"The Navajo will tell you it was a powerful place ruled by a man who misused his power for black magic," Stein said.

"This place was in the service of the devil," he said. "It was like (the Nazi concentration camp) Auschwitz."

According to some of the Navajo stories, the Gambler enslaved the people he outwitted and forced them to build the Chaco great houses. The Gambler claimed one of the sandstone structures, Pueblo Alto, as his home.

After abusing his office and mistreating the masses, the Gambler was beheaded.

Then the large, circular ceremonial rooms within the great houses, known as great kivas, were razed "so that the power they created couldn't be abused" ever again, Stein said.

Various ceremonial secrets were bestowed on a handful of medicine men, who were then sent away from Chaco "in a deliberate diaspora to break up that power so it couldn't be drawn together again in one place," Stein said.

The building boom in Chaco Canyon ended in the mid-1100s and the region's population center shifted northward.

By 1300, Chaco Canyon and most of the northern Southwest had been abandoned by the Anasazi. Drought may have contributed to the abandonments.

Who were the Chacoan People?

• History: Inhabited Chaco Canyon A.D. 850-1250. Built area into a trading hub 1020-1120. Migrated to new areas 1100-1200.

• What they built: Canyon inhabitants were skilled masons and built multistory stone houses with hundreds of rooms oriented to solar, lunar and the four cardinal directions; also built roads between great houses.

• Culture: Included astronomical markers and water-control devices in great houses. May have used great houses as public ceremonial and trading centers. Made distinctive black-on-white Cibola pottery. Treasured turquoise for jewelry and trade.

• Anasazi or Ancient Puebloan?: Anasazi is a Navajo word for "enemy ancestors," a name Anglo explorers and archaeologists gave to prehistoric peoples of the Four Corners region. Some American Indians find Anasazi offensive and prefer Ancestral Puebloan or Ancient Puebloan.

Ping.

Good article. Sounds like the legends are fairly coherent. There is probably some truth in them.

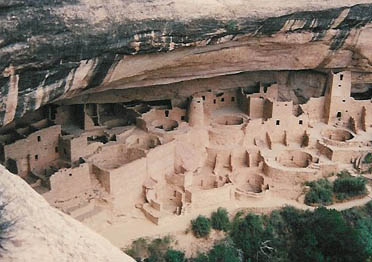

I think this (#3) is Mesa Verde.

Bump. I enjoy reading articles about the four corners area. My father was an oil field worker and I remember him bringing home arrow heads and beads that he would find on red ant piles. Although it didn't awe me as much when I was a child, I now marvel at the cliff dwellings. We even spotted ruins on the cliffs of the Navajo Lake. We revisited the Mesa Verde ruins this past summer and the more mature I get the more impressed I am. Not too thrilled about the cannibalism theories, though that would explain how they might have fed large gatherings.

That was my first thought, too.

During one trip to Chaco, I was in thunderstorm, poured rain and the water sat on top on the of impermeable sandstone like a lake.

They liked round structures. Well, so do Christians and Muslims. Probably some superstition behind the lack of corners.

Nancy Yaw Davis

The Zuni Enigma

Did a group of thirteenth-century Japanese journey to the American Southwest, there to merge with the people, language, and religion of the Zuni tribe?

For many years, anthropologists have understood the Zuni in the American Southwest to occupy a special place in Native American culture and ethnography. Their language, religion, and blood type are startlingly different from all other tribes. Most puzzling, the Zuni appear to have much in common with the people of Japan.

In a book with groundbreaking implications, Dr. Nancy Yaw Davis examines the evidence underscoring the Zuni enigma, and suggests the circumstances that may have led Japanese on a religious quest-searching for the legendary "middle world" of Buddhism-across the Pacific and to the American Southwest more than seven hundred years ago.

Nancy Yaw Davis holds an M.A. from the University of Chicago and a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Washington. Author of numerous articles, she has long researched the history and cultures of the native peoples of North America. Her company, Cultural Dynamics, is located in Anchorage, Alaska, where she lives.

well, the sun and the moon are round.......

"The town and the term is Russian for tumulus, the distinctive mound-grave of the nomadic culture to whom the name Kurgan was given."

Interesting. I did an internet search and found the reviews of this book are all over the place. Sounds very interesting.

I hundreds of photos of Mesa Verde, Hovenweep, Chaco, Aztex(sp) and many smaller house and cliff dwellings in Four Corners.

I just don't have time at the moment to post some.

I don't believe this pic is Chaco Canyon.

Great pics of Mesa Verde! The pic on your page, "Hoodoo"--isn't that Camel Rock?

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.