The Resurrection, Piero della Francesca, 1460

Posted on 09/21/2013 10:12:13 AM PDT by SeekAndFind

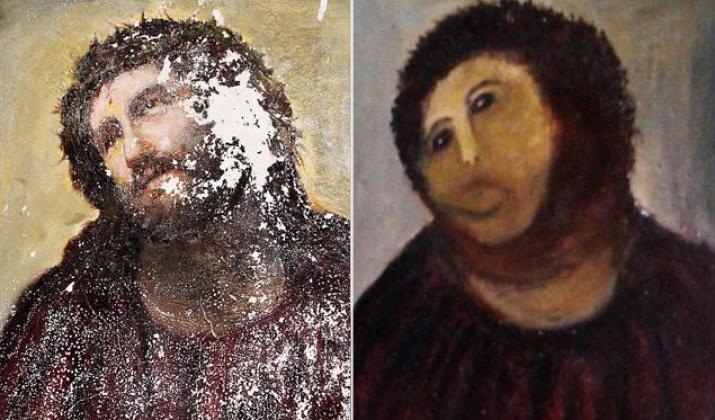

It was in a 1925 essay entitled “The Best Picture” that Aldous Huxley made the claim that a 1478 fresco painting by Piero della Francesca (1420–92), in the little Italian town of San Sepolcro (Holy Sepulcher) in the upper Tiber valley, was “the greatest picture in the world.” It is true that critics and connoisseurs before Huxley, and many after him, also made very high claims for Piero’s relatively few surviving paintings. Much of his work, sadly, was destroyed shortly after his death, and in the early 1800s vandalistic Napoleonic French troops fired damaging shots at his great fresco series The Legend of the True Cross (1452–66) in the Church of St. Francis during their occupation of the city of Arezzo.

Some 50 years after Piero’s demise, the great biographer of the classic Italian painters, Giorgio Vasari, praised him highly in his Lives of the Artists. Over the last 150 years numerous Anglophone scholars and critics have expressed vast admiration for Piero: John Addington Symonds in the 1880s, Bernard Berenson in 1902, Kenneth Clark in a great monograph in 1951, John Russell, art critic for the London Sunday Times and the New York Times, in the 1960s: “He had the kind of total comprehension which makes us trust in him, unreservedly. . . . He is for us the first and the greatest of classical painters. . . . He has my vote, any time, as the Perpetual President of European painting.”

Berenson wrote that in the presence of “certain Giottos, Masaccios, and Pieros . . . it is not the physical but the ethical, the moral weight that overawes us.” Fifty years earlier, after discussing Piero’s technical excellences, Berenson had written of him: “judged as an illustrator, it may be questioned whether another painter has ever presented a world more complete and convincing, has ever had an ideal more majestic, or ever endowed things with more heroic significance.” When the great art historian, museum administrator, humanist, and television broadcaster Sir Kenneth Clark first saw colored photographs of Piero’s Legend of the True Cross fresco cycle, “I immediately felt a sense of pre-ordained harmony different from anything I had known.” He added that Piero’s Baptism of Christ gave him “more intense aesthetic delight than any other painting in the [British] National Gallery,” of which he was then the director. Clark reports that when he first saw the diptych by Piero of Duke Federico da Montefeltro and his duchess in Urbino, he fell to his knees. Another distinguished art historian, John Pope-Hennessy, later claimed that Piero’s Flagellation of Christ was “the greatest small painting in the world.”

So Aldous Huxley is in good company in his praise. But is Piero’s Resurrection of Christ in little San Sepolcro “the greatest picture in the world”? Huxley’s own argument is initially interesting and powerful but ultimately oblique and incomplete — oddly so, given that he was one of the best-educated, most verbally clever, and most sheerly intelligent of major 20th-century writers. He admits that the contention that Piero’s Resurrection is “the greatest picture in the world” is in one sense obviously “ludicrous” because there are “a great many kinds of merit and an infinite variety of human beings.” But he fends off the common, nihilistic modern argument that art “is all a matter of personal taste,” saying that there is “an absolute standard of artistic merit,” which is “in the last resort a moral one.” He thinks “genuineness” always “triumphs in the long run”; he asserts that Piero della Francesca’s painting is “absolutely great, because the man who painted it was genuinely noble as well as talented.” But Huxley longingly refers to a purified classical humanism as a defensible ideal: “the religion of Plutarch’s Lives” and “the resurrection of the classical ideal, incredibly much grander and more beautiful than the classical reality.” He tells us, counterintuitively and unpersuasively, that Piero’s ostensible subjects, the Christian religion and the Resurrection of Christ, are not really central to his art.

Twenty-six years and much painful history later, in 1951, another self-styled aesthete, Kenneth Clark, is equally sure of the greatness of the painting and the painter, but he manages to go much deeper, perhaps affected by the tragedy and pathos of the previous 40 years of European and world history, including two world wars and millions of unmarked sepulchers: “But before Piero’s risen Christ we are suddenly conscious of values for which no rational statement is adequate; we are struck with a feeling of awe. . . . This country god, who rises in the grey light while human beings are still asleep, has been worshipped ever since man first knew that seed is not dead in the winter earth, but will force its way upwards through an iron crust.”

Clark has realized, and realized that propositional language is not altogether fit to express, certain fundamental truths of the human condition to which artistic, ritual, musical, doctrinal, and symbolic representation give the only real access, and perhaps only in what he calls “moments of vision.”

At some level the question of whether Piero’s Resurrection of Christ is the “greatest picture in the world” is of course absurd, because no merely technical analysis invoking pictorial or other specifiable aesthetic values is ever adequate to estimate the ultimate value and success of a work of art. We cannot prescind altogether from the topic, subject, theme, meaning, or recognizable or paraphrasable content of a work of art. However, today, as the critic Morris Dickstein has said, “art since Warhol is whatever you can get away with.” There are no canons but the market, driven by a kind of mindless dynamism and fashion. The more transgressive of traditional standards, sensibilities, and ethics, the better; “neophilia,” profanity, and obscenity reign. So aesthetic claims are inevitably and only claims of subjective pleasure or satisfaction: I like it.

But though Huxley was throughout his life an ambiguous aesthete, a very dark angel, he had some profound intuitions. “Five words sum up every biography,” he wrote: “‘Video meliora proboque, deteriora sequor’”; “I see and approve the good, but follow the bad.” He sought in art and spirituality, and alas in more ambiguous ways too, what he called “the lost purpose and the vanished good.”

What the many admirers of the Christian Platonist Piero (and of other great orthodox artists such as Dante, Bach, Shakespeare, and Eliot) may dimly understand, and cling to, is that both religion and idealism — including duty and honor in one’s work and daily life — are kept alive by a faith: a faith that we live in a metaphysical and moral as well as a physical universe, that true value ultimately triumphs over inert or brutal fact, that spirit triumphs over flesh — if not here, then hereafter — and a whole series of similar distinctions and convictions: altruism and love over self-interest and envy; justice over indifference, cruelty, and crime; mind over matter; grace over gravity; cosmos over chaos; purpose over chance and necessity. We are saved from cynicism and despair by such faith, and its greatest symbol is the Resurrection.

Piero’s subject and his exquisite portrayal of it are in fact what make it credible to say that his visionary Resurrection is the greatest of all paintings, because he binds together inextricably the visceral, the aesthetic, the ethical, and the religious with the kind of integrity and synthesis of expression that the human person yearns for and so often misses or lacks. The American poet Edwin Markham put the insight poignantly over a hundred years ago:

In spite of the stare of the wise and the world’s derision,

Dare travel the star-blazed road, dare follow the Vision.

It breaks as a hush on the soul in the wonder of youth;

And the lyrical dream of the boy is the kingly truth.

The world is a vapor, and only the Vision is real;

Yea, nothing can hold against Hell but the Wingèd Ideal.

Having served as a lay religious leader and on the town council, Piero della Francesca lost his sight during the last decade of his life in his small home city, San Sepolcro, and he turned to pursuing the beloved mathematical investigations that brought him later eminence, along with his gifted friend and countryman, Fra Luca Pacioli. Though there is a statue of Piero in San Sepolcro, nobody really knows what he looked like after his youth; but a lantern-maker from his town, Marco di Longaro, has been remembered in history because when he was a small child he “used to lead by the hand Master Piero della Francesca, who was blind.”

Late in World War II, in the summer of 1944, on a hill in the upper Tiber valley, a young artillery officer in the vanguard of the British 8th Army was ordered on the radio by his superior behind the lines to shell a small German-occupied Italian town in the valley beneath him to drive the Germans out and safely prepare for the British advance. The town was San Sepolcro, and the young officer had read Huxley’s essay on the great painting. Making ambiguous, evasive excuses on the radio to his superior, he disobediently held off shelling, risking grave consequences for the British forces, including himself, if they had encountered lethal resistance. But the next day the Germans withdrew without a major altercation. A street just outside San Sepolcro is now named for him.

— M. D. Aeschliman is professor of Anglophone culture at the University of Italian Switzerland. He recently edited a new edition of Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities (Ignatius Press).

Dude, it’s even better on acid.

Great painting; great story of the young British soldier who save this from destruction.

It’s “Elvis on velvet” - nothing else is close....

Seriously!

GREATEST is subjective term and should NEVER be confused with "biggest grossing" or "most expensive".

Take a look at the

10 most expensive photos sold (often at auction)

The Billy the Kid photo's value is concentrated in the historical worth, not the "art" of the image.

2 are Cindy Sherman self portraits (or Selfies as the grownups trying to sound hip are calling them today)

The Pond/Moonlight, by Edward Steichen has historical significance and is an "early master". It's also 1 of only 2 prints of the image (both hand-colored). It isn't his greatest work.

3 are contemporary "landscapes" by Andreas Gursky.

One is a plagiarism from a Marlboro cigarette ad.

On the whole, none of them qualify as The Greatest Photo.

If you agree with Huxley here, you can (and should) apply his standard to other art forms. I do.

You have to admit that "Dogs Playing Poker" is right up there, too.

“Modern art” was created to be ANTI-art. Anti-art has now become the dominant art form of the 20th century.

Time for genuine art to return into view.

http://hubpages.com/hub/coolidge-dogs

Coolidge Dogs: A History of the Poker and Pool-Playing Dogs

Unfortunately “GREATEST” is always confused with “biggest grossing” or “most expensive”. Take the recent thread about the Eagles being the reason for a domestic violence incident. Jokes, links to Big Lebowski (”I hate the Eagles!), dissing the Eagles, and one poster near the end persuading us, of God only know what, by citing the number 27 million (copies of greatest hits sold.) Note the sometime weekly threads of highest grossing movies in the past weekend. So what?

If anyone believes any of that, he oughta run to the Amazon bookstore and buy the latest by Danielle Steel (and all the 100 previous “novels” of hers.)

Modern art was created to show that art was more than just illustration, that color and form have their own aesthetics separate from any narrative subject.

The whole subject of this article points to why modern art developed. It says that the greatest painting ever was painted over 500 years ago. Modern art says "Okay, now what?"

Irving Azoff was behind the Eagles marketing/management. He also was at MCA Records when countless scams were run on the books and inventory to appear to have profit and chart success.

That’s a “transformative” work.

I always remember that the lamp post is dead center on that canvas, even though you’d swear it’s to the right.

Right on.

If you have trouble recognizing greatness, it's easier to recognize garbage, which is almost all modern.

Absolutely! Read Thomas Wolf’s The Painted Word. He explains how modern art came about.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.