Posted on 11/27/2011 5:05:41 AM PST by Homer_J_Simpson

* Note the subtitle to the first of the stories from Libya, “Italians Claim 5,000 Captives, Including U.S. Journalists and Army Observers.” Among the captured journalists is Harold Denny, who filed the next article, “Desert Tank War is Hard to Follow.”

** GSD ping.

http://www.onwar.com/chrono/1941/nov41/f27nov41.htm

Red Army recaptures Rostov

Thursday, November 27, 1941 www.onwar.com

Soviet T-26 tanks in the Moscow areaOn the Eastern Front... Soviet forces have now retaken Rostov. The German Panzer Group 1 is retreating toward Taranrog. In the Moscow region, Guderian’s forces have been fighting around Kashira for three days. Further advancement without re-enforcements is not possible.

From the United States... The US issues a war warning to their overseas commanders.

In North Africa... The 4th and 6th New Zealand Brigades join with forces from the Tobruk garrison at El Duda. The German and British tanks forces engage in the Sidi Rezegh area. The German Afrika Division zbv is renamed 90th Light Division. The famous trio of the 15th Panzer Division, 21st Panzer Division and 90th Light Division, which are associated with the name Afrika Korps, is thus complete.

In East Africa... The Allies attack the Italian position at Gondar. It moves quickly despite the rugged terrain. Italian General Nasi, decides to ask for surrender terms.

http://homepage.ntlworld.com/andrew.etherington/month/thismonth/27.htm

November 27th, 1941

GERMANY:

U-598 commissioned.

U-192 laid down.

U-605, U-606 launched. (Dave Shirlaw)

DENMARK: Copenhagen: Two days of riots follow the government’s signing of the anti-Comintern pact in Berlin.

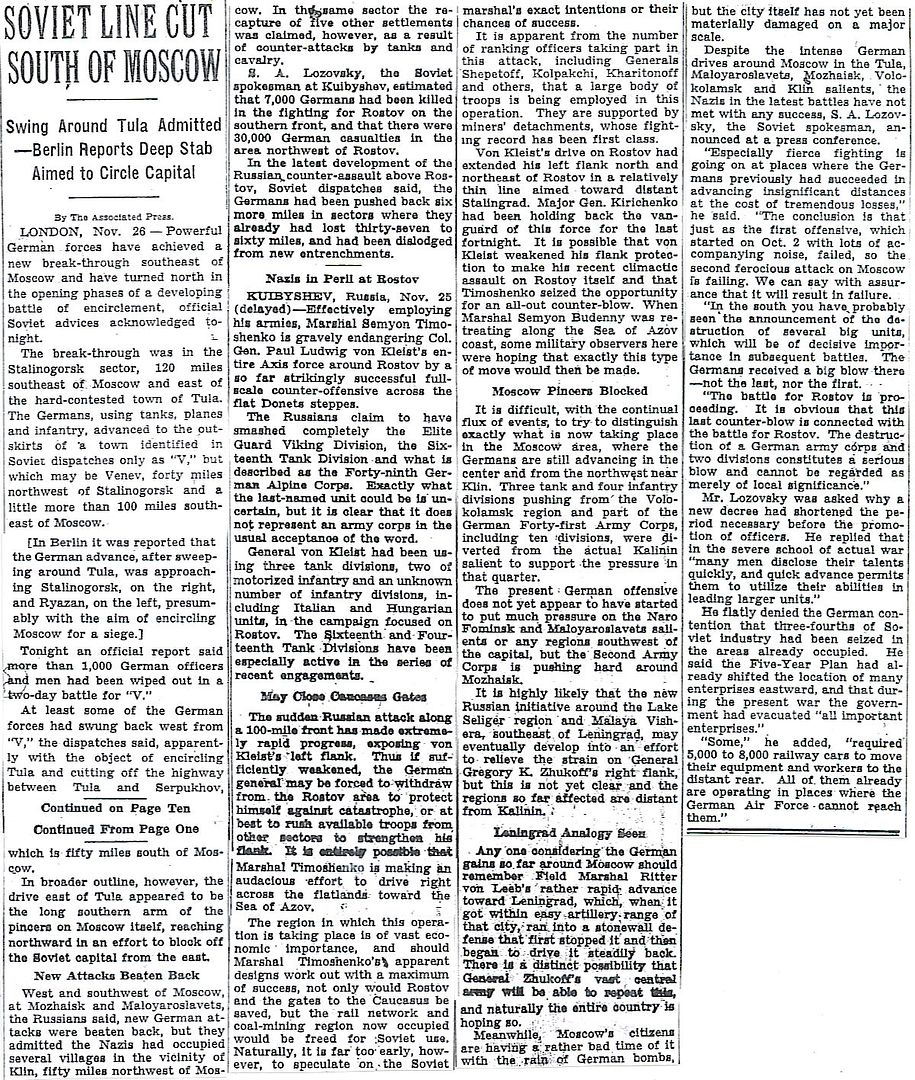

U.S.S.R.: The German 1st Panzer Group is retreating toward Taganrog as the Soviets reoccupy Rostov-on-Don.

Fighting near Kashira has been continuing for the past 3 days. Guderian’s forces will not be able to continue the advance toward Moscow unless reinforced.

Moscow: The sound of the guns from the battle raging in front of Moscow can be heard clearly in the capital tonight. The Germans are only 25 miles away. They have broadened the wedge that they have driven into the Russian forces northwest of the city and are claiming to have captured the town of Klin. They are however, still being held at Tula, south of Moscow.

The seriousness of the situation is reflected in an order of the day broadcast to the Red Army today, urging the soldiers to hold on; “The enemy has advanced nearer to Moscow. The situation is increasingly difficult but we must, and can, stand the strain.”

The order went on to say that Hitler is putting everything into his last thrust, which he hopes will bring him to the gates of the city, and, recalling the French at Verdun, it demanded: “You must fight to the last. The enemy shall not pass.”

In their advance toward Moscow under extremely difficult wintry conditions, units of 9.Armee reach the Volga Canal 60 miles (97 kilometers) northwest of the Soviet capital. Some armed patrols have penetrated the western suburbs of the city and got a good look at the Kremlin. (Jack McKillop)

The only unit to reach/cross the Volga Canal was the 7 Pz.Div. of LVIPz.K./3rd Pz.Armee. They cross the canal today at Yachroma, about 30 miles North of Moscow. (Jeff Chrisman)

SPAIN: U-652 received supplies from a support ship in Cadiz during the night. (Dave Shirlaw)

MEDITERRANEAN SEA: U-559 torpedoes and sinks the Australian sloop HMAS PARAMATTA which is escorting an ammunition ship off Tobruk at 32 20N, 24 35E, killing 138 on board and leaving 20 survivors. (Alex Gordon)(108)

At 2203hrs U-96 reached the German tanker and support ship Vessel in the harbour of Vigo. The boat left harbour at 0400hrs. In the Mediterranean, U-557 saw an enemy submarine periscope and heard her engines, but no attacks occurred. (Dave Shirlaw)

LEBANON: Beirut: The Free French General Georges Catroux proclaims Lebanon’s independence.

NORTH AFRICA: The 4th and 7th New Zealand Brigades link up with forces from the Tobruk garrison at El Duda early today. Later the Germans and British fight an evenly matched armour to armour engagement near Sidi Rezegh. The German Afrika Division is renamed the 90th Light.

Staff Sergeant Delmer E. Park, US Army Signal Corps ASN 6281980 142nd Armored Signal Company Killed in Action Sidi-Omar, Egypt. Possibly the first American to die with Allied ground forces. (Mark Conrad)

ETHIOPIA: Gondar: The last Italian forces in Ethiopia have surrendered. After holding out for nine months, aided by the mountains and the rains, General Nasi’s battle-hardened troops were overwhelmed today. The British have taken 11,500 Italian and 12,000 native troops prisoner.

Previous British assaults on Gondar have failed. Remembering only the collapse of the Italian armies in mobile warfare in the deserts of Libya and Somalia, the British forgot the Italian infantryman’s skill at positional warfare. At times, when the Italians were facing Ethiopian “Patriots” unsupported by air cover they even advanced. After whittling away at the Italian defences for six days the 12 East African Division under the redoubtable Major-General C C Fowkes, began its attack on a broad front early this morning supported by the South African Air Force.

At 7,000 feet above sea level - in bitter cold - the King’s African Rifles were advancing through clouds. By midday the battle had been decided, but there was almost a massacre when Ethiopian Patriots got into Gondar before the East Africans. Fowkes had to send in armoured cars to rescue the Italian prisoners.

CHINA: U.S. passenger liner SS President Madison, chartered for the purpose, sails from Shanghai with the 2d Battalion, 4th Marine Regiment embarked, bound for the Philippine Islands. (Jack McKillop)

JAPAN: Combined Fleet sailed for Pearl Harbor strike. (Marc Small)

COMMONWEALTH OF THE PHILIPPINES: 8:00 pm Unidentified aircraft spotted at high altitude over central Luzon by Iba radar. All FEAF units placed on alert.

Ickes and LaGuardia (US Civil Service Co-Ordinator) opined that all civil defence in the Philippines was the responsibility of the High Commissioner and that the Commonwealth government had no role to play in this.

Hart authorizes reconnaissance flights over Japanese troop convoys.(Marc Small)

TERRITORY OF HAWAII: USN Communication Intelligence Summary, 27 November: “General.-Traffic volume a little below normal due to poor signals on the frequencies above 7000 kcs. Tokyo-Takao (Formosa) circuit unreadable on mid-watch. Some tactical traffic intercepted from carriers. Bako, Sama, and Saigon active as originators, addressing traffic to each other and to the Chiefs of Staff of Second, Third Fleets and Combined Air Force. Bako addressed the Chief of Staff Third Fleet information Destroyer Squadrons Four and Five and Chief of Staff Second Fleet. The main Tokyo originator today was the Intelligence activity who sent five dispatches to the major commanders. The Direction Finder activity was very high with all stations sending in bearings including the Marshall Islands Stations which has been silent for the past four days.

- COMBINED FLEET.-No further information as to whether or not Destroyer Squadron Three is in Hainan area but is believed to be still with Cruiser Division Seven in that area. There is still no evidence of any further movement from the Kure-Sasebo area. The Chief of Staff Combined Fleet originated several messages of general address. He has been fairly inactive as an originator lately. CinC. Second Fleet originated many messages to Third Fleet, Combined Air Force and Bako.

- THIRD FLEET.-Still holding extensive communication with Baka, Sama South China Fleet and French Indo China Force. The use of WE addresses is increasing, those occurring today were: “DAIHATIFUTABUTAISANBOTEU” (in Taihoku) “KOROKUKITISIKI” “KIZUKEYAMASITABUTAI” (in care of RYUJO) “HEIZEUKAIGUNDAIGONREUSEU” There is nothing to indicate any movement of the Third Fleet as yet.

- FOURTH FLEET.-CinC. Fourth Fleet frequently addressed dispatches to the defense forces in the Mandates. Jaluit addressed messages to the Commander Submarine Force and several submarine units. The Saipan Air Corps held communication with Jaluit and CinC. Fourth Fleet. The Civil Engineering Units at IMIEJI and ENIWETOK were heard from after being silent for weeks. Chitose Air Corps is in Saipan and Air Squadron Twenty-four is still operating in the Marshalls. No further information on the presence of Carrier Division Five in the Mandates.

- AIR.-An air unit in the Takao area addressed a dispatch to the KORYU and SHOKAKU. Carriers are still located in home waters. No information of further movement of any Combined Air Force units to Hainan. SUBMARINES.-Commander Submarine Force still in Chichijima Area.” (Jack McKillop)

U.S.A.: President Roosevelt and Secretary of State Hull decide to present a stiff note of final terms to the Japanese. It requires recognition of the Nationalist Chinese Government, the withdrawal of Japanese troops from China and Indonesia. The US promises to negotiate new trade and raw materials (oil and scrap metal) agreements.

US military authorities issue a war warning to their overseas commanders.

Destroyers USS Jenkins and La Vallette laid down.

Escort carrier USS Nassau laid down. (Dave Shirlaw)

ATLANTIC OCEAN: USN destroyer USS Babbitt (DD-128), with Task Unit 4.1.5, escorting convoy HX-160 (Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, to U.K.), depth charges a sound contact. (Jack McKillop)

10 days to go......

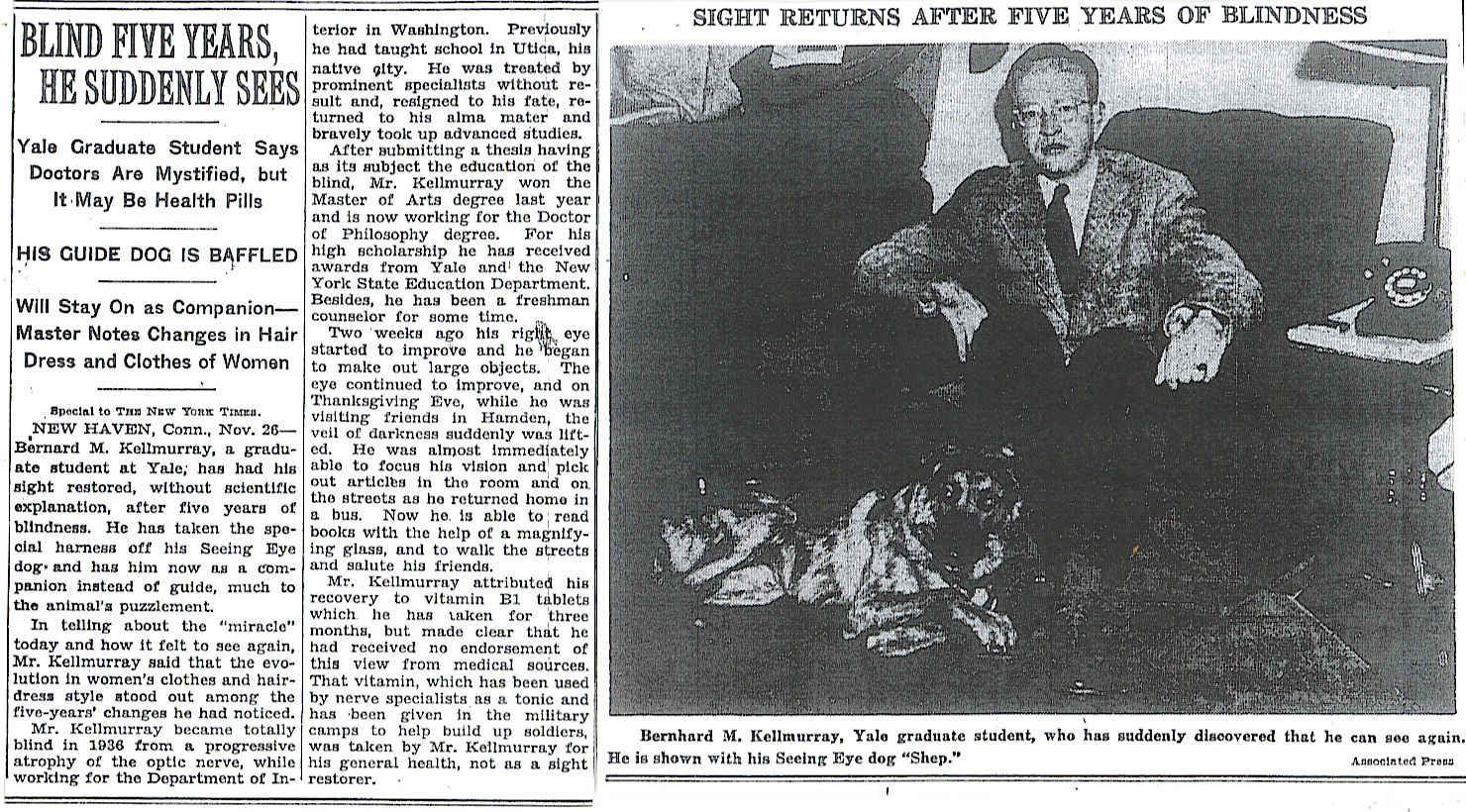

Enjoyed the article on the man who can see again & attributes the fact to vitamin B1.

“Guide Dog Mystified” - lol.....

How'd that work out for you, Secretary Hull? Oh, yeah, just like you planned /s

Pardon me...

I shoulda stated:

“Guide Dog Baffled” - lol....

And the Marines and China Fleet are evacuated from that country.

intersting articles about the guy. this one says he had an operation to restore his sight.

frankly, my BS meter is pinging. do you think the guy could have faked it for those years than decided he had enough of the blind act and took some viatmin pills and declared himself cured? could be eh?

A cold sullen dawn stole over Hitokappu Bay on Wednesday November 26. Low surface clouds hung from a leaden sky. Snow spilled to earth and swirled over the surface of the water so that each ship saw her neighbor only as a gray indistinct shape in the semidarkness

Blinker signals stabbed through the erie half-light. Then at the stroke of 0600-which was 1030 November 25 in Hawaii and 1600 November 25 in Washington- decks and ladders thudded with the hurried steps of officers and men speeding to stations. Shouted orders pierced the air, the pull of giant chains sent cries of tortured steel across the bay. Huge turbines droned in the engine rooms as powerful propellers slashed the water. Akagi’s anchor chain stuck, delaying the sailing half an hour and sending a ripple of consternation through the superstitious. Then, one by one, the vessels of the task force glided like ghost ships from their secluded rendezvous and plunged into the Pacific.

It sure sounds like it!

It sure sounds like it!

"But pray ye that your flight be not in the winter . . ."

On 14th December at 1300 hours a Russian second lieutenant with a white flag appeared in front of Captain Hingst, commanding 8th Company, 3rd Panzer Regiment, who was employed with units of 2nd Rifle Regiment along the southeastern edge of the town as part of the combat group Hauser. The Soviet officer carried a letter signed "Colonel Yukhvin" and demanding the surrender of Klin.

"The position of the defenders is hopeless," the Soviet colonel wrote.

It was the first Soviet invitation to surrender presented under a white flag on the Eastern Front.

Captain Hingst treated the Russian very courteously and, having reported to Colonel Hauser and asked for instructions, sent him back at 1400 with the answer that the colonel was mistaken, the situation was by no means hopeless for the defenders.

Hingst was right. The disengagement of LVI Panzer Corps (from Klin) had meanwhile progressed according to plan. At 16.30 hours, when the road had been cleared, the 1st Panzer Division with its motor-cycle battalion moved off to the west. By 15th December all units had reached the interception line of 2nd Panzer Division at Nekrasino. On the southern edge of the town Colonel Hauser withdrew his forces over the small Sestra river into the western part of the town itself. As soon as the last tank was across, the bridge was blown up. Headquarters and combat groups of 53rd Motorized Infantry Regiment, as well as the Tank Company Veiel of 2nd Panzer Division, held Klin, by then in flames, until 2100 hours. Then this rearguard likewise moved off to the west.

The Russians infiltrated into the town.

Klin was lost. The front of 3rd Panzer Group had been pushed in. The German armored wedge aiming at Moscow from the north had been smashed. The two Soviet Armies, the Thirtieth and the First, had succeeded in eliminating the dangerous threat to Moscow. On the other hand, the Soviets had not succeeded in annihilating 3rd Panzer Group. Thanks to the bravery of the fighting forces and the skilful handling of 1st Panzer Division, the divisions of two Panzer Corps and units of V Army Corps had been successfully saved from encirclement, and the men as well as a large proportion of the weapons and material withdrawn to the Lama position 56 miles farther back.

But what was the situation like at the other focal points of the Moscow front—with 4th Panzer Group west of the city and with Guderian's Second Panzer Army down in the south?

Moscow is situated on the 37th meridian. On 5th December the two wings of Guderian's Panzer Army, which were to have enveloped the Soviet capital from the south, stood with 17th .Panzer Division before Kashira, about 37 miles north of Tula, with 10th Motorized Infantry Division at Mikhaylov, and with 29th Motorized Infantry Division north-west of Mikhaylov.

Mikhaylov, however, is on the 39th meridian. In other words, Guderian was well behind the Soviet metropolis. The Kremlin, in a sense, had already been overtaken. As a result, Guderian's thrust, though still 75 miles south of Moscow, was every bit as dangerous as the armored wedge in the north which had got within some 20 miles of the Kremlin. For that reason Guderian's front, the area from the southern bank of the Oka via Tula to Stalinogorsk, became the second focus of the Soviet counter-offensive.

The Soviet High Command employed three Armies and a Guards Cavalry Corps in a two-pronged operation designed to encircle Guderian's much feared striking divisions and annihilate them.

The Soviet Fiftieth Army formed the right jaw of the pincers, and their Tenth Army the left jaw. General Zhukov—the leading brain of the Soviet High Command, who was personally in charge of the Soviet counter-blow at Moscow —tried to apply the German recipe here in the south, just as he had done with General Kuznetsov's formations in the north, at Klin. He tried to pinch off the protruding front line of Second Panzer Army, and to do it so quickly that the German divisions were left no time to withdraw.

It was a good plan. But Guderian's strategic perception was even better. On 5th December Guderian's attempt to achieve a link-up north of Tula between 4th Panzer Division and 31st Infantry Division, with a view to encircling the town finally, had failed. As a result, the Second Panzer Army was tied down in heavy defensive fighting. During the night of 5th/6th December, the night preceding the Soviet offensive, Guderian therefore ordered the withdrawal of his exhausted forward formations to the Don-Shat-Upa line. This movement was in progress when, on 6th and 7th December, the Russians charged against LIII Army Corps and XLVII Panzer Corps at Mikhaylov. They encountered only the rearguards, which offered delaying resistance and covered the withdrawal already in full swing.

Even so, things were bad enough.

The retreat in icy wind through waist-high snow, over mirror-smooth roads, was hell. Not infrequently the formations, as they painfully struggled along the roads, were involved in skirmishes with fast Siberian ski battalions. Like ghosts the Siberians appeared in their white camouflage smocks. Soundlessly they approached the road on skis through the deep snow. They fired their rifles. They flung their hand-grenades. And instantly they vanished again. They blew up bridges. They blocked important crossroads. They raided supply columns and killed the men and the horses.

But Guderian's battle-hardened divisions were no inexperienced supply rabbits.

The 3rd Panzer Division, for instance, was withdrawing with its vehicles from the area north of Tula, from one sector to the next, through an icy blizzard. Fast mixed rifle companies with their armored infantry carriers, anti-tank guns, and self-propelled anti-aircraft guns formed their rearguard or even acted as assault reserves for 3rd and 394th Rifle Regiments. When the bulk of their units had detached themselves from the enemy these mixed companies launched swift counter-attacks or, by continuously changing their position and rapidly firing all their automatic weapons, produced the impression and the sound effects of strong formations. On suitable occasions they would even launch lightning-like counter-blows over distances of three to six miles.

One such occasion arose near Panino on 14th December. The regiments had to cross the bridge over the Shat. The Russians were putting on the pressure with tanks and ski battalions. The villages in front of the bridge had to be burnt down to gain a clear field of fire and to deny cover to the Soviets.

Second Lieutenant Eckart with his 2nd Company, 3rd Rifle Regiment, was covering the vital road fork. The Russians came in battalion strength—Uzbeks of a Rifle Regiment of Fiftieth Army. With them, in their foremost line, were anti-tank guns and heavy mortars. Eckart sent a signal to Second Lieutenant Lohse, commanding 1st Company, in which all the armored troop carriers of the rifle regiments were grouped: "I require support." Lohse quickly collected four tanks to add to his halfdozen armored troop carriers and drove off. Behind the smoldering ruins of a village he cautiously crept up against the flank of the attacking Russians.

Now!

They broke cover. Three Soviet anti-tank guns were over-run. The Russians were driven into the fire of 2nd Company. Those who were not killed pretended to be dead—a favorite Soviet trick.

Lohse's command carrier was the last to cross the bridge.

The squat silhouette of a T-34 appeared on the horizon. It fired. But its aim was poor. The Germans succeeded in blowing up the bridge. Lohse's armored troop carrier company had lost one vehicle carrying an anti-tank gun. Sergeant Hofmann was wounded, and one man was missing. But an entire Soviet battalion had been destroyed.

Men like Lohse and Eckart—second lieutenants and sergeants, captains as much as machine-gunners or the drivers of tanks, of armored infantry carriers, gun tractors, lorries or horse-drawn vehicles of every kind—these were the men who tackled the situations which were frequently critical for entire combat groups or divisions. The dramatic retreat through blizzard and fire made the German front-line soldier hard; it produced that tough, patiently suffering, self-reliant, and enterprising individual fighter without whom the German armies in the East could not have survived the winter before Moscow.

The cruelty of the winter, its savagery towards German and Russian alike, was gruesomely illustrated for a rearguard of 3rd Rifle Regiment on the fourth Sunday in Advent of 1941.

It happened at Ozarovo.

Through his binoculars the second lieutenant spotted a group of horses and troops standing on a gentle slope in the deep snow. Cautiously the German troops approached.

There was a strange silence. The Soviet group seemed terrifyingly motionless in the flickering light of the snowy waste.

And suddenly the lieutenant grasped the incredible—horses and men, pressed closely together and standing waist-deep in the snow, were dead.

They were standing there, just as they had been ordered to halt for a rest, frozen to death and stiff, a shocking monument to the war.

Over on one side was a soldier, leaning against the flank of his horse. Next to him a wounded man in the saddle, one leg in a splint, his eyes wide open under iced-up eyebrows, his right hand still gripping the disheveled mane of his mount.

The second lieutenant and the sergeant slumped forward in their saddles, their clenched fists still gripping their reins. Wedged in between two horses were three soldiers: evidently they had tried to keep warm against the animals' bodies. The horses themselves were like the horses on the plinths of equestrian statues—heads held high, eyes closed, their skin covered with ice, their tails whipped by the wind, but frozen into immobility. The frozen breath of eternity.

When Lance-corporal Tietz tried to photograph the shocking monument the view-finder froze over with his tears, and the shutter refused to work.

The shutter release was frozen up. The god of war was holding his hand over the infernal picture: it was not to become a memento for others.

Like 3rd Panzer Division, the other divisions of Guderian's two Panzer Corps likewise withdrew from the frontal arc northeast of Tula, fighting all the time against the attacking Soviet Fiftieth, Forty-ninth and Tenth Striking Armies, and thus evaded the pincer operation, the bear-hug in which Zhukov wanted to clasp the Second Panzer Army.

At Mikhaylov, where on 8th December Zhukov's Striking Army made a surprise attack, the 10th Motorized Infantry Division, engaged in delaying defense, suffered considerable losses. At XXIV Panzer Corps the 17th Panzer Division halted the first Soviet thrust from the direction of Kashira. Southeast of Tula the "Grossdeutschland" Regiment stood up stubbornly against fierce Soviet attacks from inside the city, and thus defended the Corps' left switch-line covering the withdrawal towards the Don-Shat-Upa line. Under cover of these engagements the bulk of the Army retreated. Stalinogorsk was evacuated. Yepifan was abandoned after heavy defensive fighting, in accordance with orders, by the 10th Motorized Infantry Division, which had fought its way into the town on its retreat. The defensive line along the Don-Shat-Upa line was reached on 11th December.

However, Guderian's hope of holding out here proved unrealizable.

Units of the Soviet Thirteenth Army broke into the front of General Schmidt's Second Army on both sides of Yelets, south of Guderian's Panzer Army. On 13th December Yefremov was abandoned by Second Army. The 134th and 45th Infantry Divisions—some of whose units were encircled at Livny for a few days—offered desperate resistance, but were forced to give ground and march for their lives.

Lance corporal Walter Kern of 446th Infantry Regiment, 134th Infantry Division, reports:

"Whenever we moved into a village in the evening we first had to eject the Russians. And when we got ready to move off again in the morning their machine-guns were already stuttering behind our backs. Our killed comrades, whom we could not take along, lined the roads together with the dead bodies of horses, or remained lying in the ravines where we stopped to offer resistance, but which often turned out to be dangerous death-traps."

The situation was similar in the sector of 45th Infantry Division—the former Austrian 4th Division—in action south of 134th Infantry Division. Cut off at one moment, bursting through the enemy at the next, their supply columns destroyed, their operational and withdrawal directives dropped to them from the air, the combat groups of this gallant division fought their way out of the Livny pocket to the south-west.

With the front line of his right-hand neighbor withdrawn from the Yelets-Livny area to the south-west, Guderian's right wing in the Don-Shat-Upa position was left hanging in mid-air.

Guderian, therefore, had to withdraw once more, taking his line a further 50 miles to the west, to the Plava. Presently, when the Russians broke through with twenty-two rifle divisions between Yelets and Livny, Guderian was compelled to move his line back even farther. In the course of this move the connection was lost between Second Panzer Army and Fourth Army, so that a gap of 20 to 25 miles appeared in the front line between Kaluga and Belev.

The Soviet High Command seized its opportunity and launched the I Guards Cavalry Corps through the vast gap which was forming in the German lines. General Belov's Cavalry Regiment, supported by combat troops on skis and motor sledges, chased westward towards Sukhinichi and northwest towards Yukhnov.

Matters were moving to a climax.

The gap in the front became the nightmare of the German High Command. From now onward there was a danger that the southern wing of Fourth Army might be enveloped. Indeed, if the Russians succeeded in breaking through via Kaluga to Vyazma on the Moscow motor highway they might even strike at the rear of Fourth Army and cut it off. A single thrust from the north could thus close the huge pocket.

It was obvious that this was also the aim of the Soviet Command.

This bold strategic operation was positively asking to be executed. The specter of defeat, distant as yet, began to haunt the badly mauled German forces of Army Group Centre.

The Soviet High Command set about its plan correctly. Kluge's Fourth Army, in the middle of Army Group Centre, was at first exposed only to tying-down attacks. In this way the Soviets tried to prevent Kluge from switching some of his forces to the wings of Army Group, or even withdrawing his Army and employing the large formations thus freed against the Soviet offensive in the south and north. Kluge was to be pinned down in the middle of the central sector until the two jaws formed by the northern and southern Russian Army Groups had smashed the wings of the German front.

It was in just this way that Field-Marshal von Bock had dealt with the Soviets at Bialystok and Minsk, Hoth at Smolensk, Rundstedt at Kiev, Guderian at Bryansk—and Kluge at Vyazma, which was the finest example of a battle of encirclement in military history. Was Zhukov now going to do the same, this time with a Russian victory at Vyazma?

It could happen, provided the Soviets succeeded in breaking through to the west, also north of Fourth Army, and in wheeling round to the south, towards the Moscow-Smolensk motor highway.

What meanwhile was the situation on the front of 4th Panzer Group?

The VII and IX Army Corps had ground to a standstill along the Moskva-Volga Canal at the beginning of November. The IX Army Corps made one last attempt to improve its positions. One of the participants in this attempt —in these last pulse beats of the German frontal attack on Moscow by Hoepner's 4th Panzer Group along the motor highway—was Lieutenant Hans Bramer with his 14th Company, 487th Infantry Regiment, fighting under 267th Infantry Division. That was on 2nd December 1941.

The 267th Infantry Division from Hanover was to make one last attempt to break open the Soviet barrier west of Kubinka by means of an enveloping attack across the frozen Moskva river.

In a temperature 34 degrees below zero Centigrade it took hours to start all the vehicles needed to get the men and the heavy weapons into the deployment area. The artillery, on the other hand, put down a massive barrage as in the good old days. But, in spite of it, the move did not come off.

The Russians had fresh Siberian regiments in magnificently camouflaged and well-built positions in the woods. As a result, the normally so useful 3.7-cm. anti-tank guns of Brämer's 14th Panzerjäger Company were not much help, even though two troops with six guns had been attached to the assault battalions of Lieutenant-Colonel Maier's combat group. The gun crews were killed. The guns were lost. That was the end. The men had to withdraw again. They simply could not get anywhere.

The 267th Infantry Division thereupon took up its prepared winter positions a few miles farther to the north, on the western bank of the Moskva, now in the role of left-wing division of VII Corps. Beyond it to the north stood IX Corps with 78th, 87th, and 252nd Infantry Divisions. In this way the line as far as Istra was reasonably well held.

But over on the right, along the Moskva river, 267th Infantry Division, supposed to hold a sector of roughly four miles with the remnants of the weakened 497th Infantry Regiment, could do no more than man a few strongpoints, scarcely more than reinforced field pickets.

It was asking for trouble.

During the next few days the Russians continually attacked across the Moskva—sometimes with small formations and sometimes in strength. Evidently they were trying to discover the weak spots along the join between Hoepner's 4th Panzer Group and Kluge's Fourth Army. Supposing they discovered the virtually undefended gap along the Moskva on the right flank of 267th Infantry Division? The defenders kept pointing out their weakness—but without effect, since neither Corps nor Army had any reserves left which they could have dispatched to reinforce the line.

On 11th December towards 1000 hours a runner, Corporal Dohrendorf, excitedly burst into Brämer's dugout: "Herr Oberleutnant, over there on the right there are columns on skis moving to the west. I believe they are Russians!"

"Blast!" Bramer leapt to his feet and ran out.

His field-glasses went up. A suppressed curse. Bramer scurried back to the telephone. Report to Regiment: "Soviet forces, several big columns in battalion strength, are passing through the front line to the west on skis."

Action stations.

Corporal Dohrendorf and Lieutenant Bramer had observed correctly. Soviet Cossack battalions and ski combat groups had wiped out the German pickets along the thinly held Moskva strip and were now simply bypassing the well-fortified strongpoints of 467th and 487th Infantry Regiments, where the bulk of divisional artillery was also emplaced. In vain did General Martinek, commanding 267th Infantry Division, try to stop the gap with the battered companies of his 497th Infantry Regiment. He did not succeed. The Russians enlarged their penetration. Contact was lost between divisional headquarters and the two northern regiments.

The division next in the line, the 78th, which was now being threatened in its flank and rear by the Soviet penetration, flung in units of its 215th Infantry Regiment. Colonel Merker, commanding 215th Infantry Regiment, assumed command in the penetration area, and from units of 467th and 487th Infantry Regiments, 267th Artillery Regiment, and with the support of battalions and batteries of Army artillery, built up a new defensive front.

But the Russians operated very skillfully, cunningly, and boldly in the wooded country.

That was hardly surprising: the units were part of the Soviet 20th Cavalry Division—a crack formation of Major-General Dovator's famous Cossack Corps, given Guards status by Stalin on 2nd December 1941 and now proudly bearing the name of II Guards Cavalry Corps.

After their break-through the Cossack regiments rallied at various key points, formed themselves into combat groups, and made surprise attacks on headquarters and supply depots in the hinterland.

They blocked roads, destroyed communications, blew up bridges and viaducts, and time and again raided supply columns and wiped them out.

Thus on 13th December squadrons of 22nd Cossack Regiment overran an artillery group of 78th Infantry Division 12 miles behind the front line. They threatened Lokotnya, a supply base and road junction. Other squadrons thrust north behind 78th and 87th Divisions. The entire front of IX Corps now hung in the air.

The forward positions of the divisions were intact, but their rearward communications had been cut off. Supplies of ammunition and food did not get through. And there were several thousand wounded in the forward fighting area.

On 14th December, at 1635, a Cossack squadron attacked the 10th Battery, 78th Infantry Division, 16 miles behind the front, while the German battery was on the move to new positions farther back. The Cossacks attacked with drawn sabres. They cut up the surprised artillerymen and slaughtered men and horses.

The Russians likewise tried to break through along the Moscow highway and the old postal road, where 197th Infantry Division was guarding the supply routes. But the 197th was on the alert.

Wherever the Russians made penetrations with tanks they were pinned down by concentrated fire and dislodged by immediate counter-attacks. Thus it went on day after day. At 0300 the Soviets would come out of the villages, where they had been keeping themselves warm, and in the evenings they would go back.

They would take their wounded with them, but leave their dead behind.

During the night of 13th/14th December a supply column of the Cossacks, consisting of forty lorries, tried to get past the positions of 229th Artillery Regiment, 197th Infantry Division.

The temperature was 36 degrees below zero Centigrade. The recoil devices of many of the guns were frozen up. The lenses of the gunsights were frosted over and blind. The gunners scored hits nevertheless just by firing by eye. The Cossack column was smashed up at point-blank range.

But neither the determined resistance of the line along the motor highway nor the gallantry of the grenadier and artillery battalions of 197th Infantry Division, nor yet the tough and successful defensive fighting of 7th Infantry Division, in whose ranks the French volunteers also fought, was able to avert the general disaster triggered off for VII and IX Army Corps by the Cossack Corps' penetration north of the highway. There was only one thing to do—pull back the front along the entire right wing of 4th Panzer Group. The new main line for the defensive fighting was to be the Ruza line, 25 miles behind the present front line. In exceedingly hard righting the 197th Infantry Division, together with rapidly brought-up units of 3rd Motorized Infantry Division, held open the highway at the now famous, or infamous, Shelkovka-Dorokhovo crossroads for the withdrawal of the heavy equipment and the divisions of 4th Panzer Group.

The situation is well illustrated by the Order issued by 78th Division to its regiments for the withdrawal: "The main thing is to break through the enemy's barrier behind our front line. If necessary, vehicles are to be left behind and only the troops saved."

In this manner they fought their way back: the Swabians of 78th Infantry Division, whose tactical sign was Ulm Cathedral and the iron hand of Götz von Berlichingen, the Thuringians of 87th Division, the Silesians of 252nd Division, the men from Rhineland and Hesse of 197th Infantry Division, and the battalions of 255th Infantry Division.

The French legionaries trudged along next to the Bavarians of 7th Infantry Division, and their words of command in the language of Napoleon echoed eerily through the frosty nights and the icy blizzards— just as 129 years before.

Lieutenant Bramer of 267th Infantry Division and his men were now, in December, retreating along the road by which they had advanced earlier in the autumn.

They were carrying their wounded with them: two infantrymen were leading a captured Cossack horse on which sat a corporal whose leg had been torn off by a shell-splinter as far as the knee. The wound was frozen up, and in this way bleeding had been stopped. Only willpower kept the man in the saddle. He wanted to live.

And in order to live one had to make one's way westward.

Who was the man who won these victories between Zvenigorod and Istra?

Who was the man in command of the Cossacks who had broken through along the flank of VII Corps, dislodging IX Corps and forcing its divisions to retreat?

His name was Major-General Dovator. This Cossack general must have been a superb cavalry commander. Within the framework of the Soviet Fifth Army he led his Corps with extraordinary skill, daring, and dash. He led his fast cavalry formations in the manner of a tank commander—and, after all, armor was merely the mechanized successor of the old cavalry.

"A commander must be in front,"was Dovator's motto.

And he led his troops from the front. He and his headquarters squadron were invariably in the front line. More than once Major-General Dovator was cited in the Soviet High Command communiqué for personal bravery.

Soviet military sources say nothing about his origins, which rather suggests that they were not proletarian but bourgeois. He probably came from the Officers' Corps of the old Tsarist Army—one of those men of middle-class origin who embraced the military profession and became unreserved supporters of the Bolshevik regime.

252nd Infantry Division, the "Oak Leaf" Division from Silesia, was among the divisions which had to fight their way back to the Ruza line.

It was this division which took its revenge on Dovator's Cossacks and made the general pay the supreme price for his victory—his life.

An account of this episode reflects both the gallantry of the German troops and that of an outstanding Russian general who knew how to fight and how to die.

On 17th December 1941 the reinforced 461st Infantry Regiment hurled itself against Dovator's forward formations which were trying to block the route of 252nd Division near Lake Trostenskoye.

The danger was averted. All the units of the division reached the Ruza, even though it was a constant race against Dovator's cavalry regiments. On 19th December the 252nd crossed the Ruza river north of the town of the same name. But Dovator had got there too.

He did not want to let 252nd Division escape his clutches. The Ruza was frozen over. The general prepared to mount a flank attack. From the right wing he intended to strike at the Silesians across the ice of the river. The clash came near two small villages, Dyakovo and Polashkino.

Lieutenant Prigann was in position outside Dyakovo on the higher western bank of the river with the remnants of 2nd Battalion, 472nd Infantry Regiment, and 9th Battery, 252nd Artillery Regiment. On the right, in Polashkino, Major Hoffer had taken up position with the 3rd Battalion, 7th Infantry Regiment, from Schweidnitz. They were good commanding positions.

Hoffer and Prigann were determined to make good use of them.

The day was grey and cold.

In the late morning snow began to fall—light, dry December snow which was blown by the wind over the fields and the frozen Ruza. The corpses of horses, gutted motor vehicles, and men killed in action and frozen rigid were covered by its shroud.

From the edge of the forest General Dovator was watching his vanguards riding down to the river.

He could hear the exchange of fire in the distance. The Cossacks dismounted.

Dovator turned to the commander of his point regiment, Major Linnika: "Attack to the right of the vanguard!"

The major saluted and drew his sword. He issued his command. The 1st Squadron burst out of the wood. It was like a phantom chase. Past the village of Tolbuzino, down towards the river.

At that moment the German machine-guns opened up.

The squadron instantly fanned out, dismounted, and flopped into the snow. The charge had not come off.

General Dovator was annoyed.

With Major Linnika, the regimental commander, he rode down the path to the north, as far as the highroad from Ruza to Volokolamsk. This was where the spearheads of his 20th Division stood. The 14th Mounted Artillery Battalion was just moving through the forest. The time was noon.

From the edge of the forest there was a good view of Polashkino. On the roads to the west were the baggage trains of 252nd Infantry Division.

"Colonel Tavliyev," the general called out.

The commander of the 20th Division leaned forward. "We'll cross the river, bypassing the village of Polashkino on the right. Then we'll strike at the rear and the flank of those columns. I'm coming with you."

The squadrons moved off at a gallop. But no sooner were they out of the wood than they were caught in very heavy machine-gun fire.

"Deploy, colonel," the general shouted.

"Drive the fascists out of the village."

With his staff, Dovator galloped down to a hut by the river.

He leapt from his horse and patted the animal's neck. The chestnut's name was Kazbek. He was nervous. "Steady, Kazbek," the general calmed him. He threw the reins to Akopyan, his groom. "Walk him up and down a bit, otherwise he'll get cold."

Dovator watched the fighting through his binoculars. On the right Dyakovo was in flames. It was being shelled by Russian artillery. But the dismounted men of the Soviet 22nd Cavalry Regiment were pinned down. Now the 103rd Regiment was galloping out of the woods, deploying, but a moment later was likewise forced to dismount. The cavalrymen advanced on foot. They reached the ice of the river. There they were kept down by continuous German machine-gun fire.

"We've got to snatch the men up from the ice," the general shouted.

He pulled his pistol out of its holster, cocked it, and with long, loping strides ran down to the river himself. His ADC, the political officer of the headquarters squadron, the duty officer, and the headquarters guard followed him.

Less than 20 yards lay between the general and the line of men pinned down in the middle of the river. At that moment a German machine-gun burst swept across the ice from the right-hand edge of the village. Dovator stopped short as though something had frightened him.

Then he fell over heavily into a drift of powdered snow which the wind had piled up on the ice.

His ADC ran up to him. But the machine-gun was still stuttering. The German lance-corporal did not take his finger off the trigger. The little spurts of snow showed him the exact position of his bursts. They cut down also the adjutant who bore the German name of Teichman. The bursts also caught Colonel Tavliyev and dropped him down by the side of his general.

"Dogs!" screamed Karasov, the political officer. "Dogs!" His coat flying behind him in the wind, he raced over the ice to Dovator and picked him up. But just then the trail of bullets danced up through the snow and mowed him down too. Dead, he collapsed on to the ice.

At last Lieutenant Kulikov and Second Lieutenant Sokirkov succeeded in crawling over to the general. Under heavy machine-gun fire they dragged their general over the ice and carried him behind the hut. Kazbek, the stallion, reared as his dead master was brought back. At Polashkino the machine-guns were still stuttering. The infantrymen from Schweidnitz were resisting furious attacks by Shamyakin's cavalry regiment, out to avenge Dovator.

Defeats invariably need their scapegoats.

On the day General Dovator was killed in action on the Ruza the first political storm swept through the German Generals Corps.

Adolf Hitler dismissed Field-Marshal von Brauchitsch, the Commander-in-Chief Army, and personally assumed the command of all land forces.

Field-Marshal von Bock, Commander-in-Chief of the hard-pressed Army Group Centre, was given "sick leave." He was succeeded by Field-Marshal von Kluge. And Kluge was succeeded by General Heinrici as Commander-in-Chief Fourth Army.

On 20th December 1941 a very worried Guderian flew to East Prussia to see Hitler at his headquarters.

He wanted to persuade him to take the German front line back to more favorable positions, if necessary over a considerable distance. The five-hour interview was of historic importance.

It showed the Fuehrer irritable, tormented by anxiety, but resolved to fight fanatically; it revealed a powerless and obsequious High Command, resembling courtiers in uniforms; and it showed Guderian, alone but courageous, passionately arguing his case and fearlessly giving Hitler his frank opinion on the situation at the front.

The first time the word retreat was mentioned Hitler exploded.

The word seemed to sting him like the bite of an adder. It conjured up for him the specter of the Napoleonic disaster of 1812. Anything but retreat!

Passionately Hitler tried to convince Guderian:

"Once I've authorized a retreat there won't be any holding them. The troops will just run. And with the frost and the deep snow and the icy roads that means that the heavy weapons will be the first to be abandoned, and the light ones next, and then the rifles will be thrown away, and in the end there'll be nothing left. No. The defensive positions must be held. Transport junctions and supply centers must be defended like fortresses. The troops must dig their nails into the ground; they must dig in, and not yield an inch."

Guderian rejoined: "My Fuehrer, the ground in Russia at present is frozen solid to a depth of four feet. No one can dig in there."

"Then you must get the mortars to fire at the ground to make shell-craters,"Hitler retorted.

"That's what we did in Flanders in the first war."

Guderian again had to put Hitler right on his facts. "In Flanders the ground was soft. But in Russia the shells now produce holes no more than four inches deep and the size of a wash-basin-the soil is as hard as iron. Besides, the divisions have neither enough mortars nor, what's more important, any shells to spare for that kind of experiment. I myself have only four heavy howitzers left to each division, and none of them has more than 50 rounds. And that is for a front sector of 20 miles."

Before Hitler could interrupt him Guderian continued: "Positional warfare in this unsuitable terrain will lead to battles of material as in the First World War. We shall lose the flower of our Officers Corps and NCOs Corps; we shall suffer gigantic losses without gaining any advantage. And these losses will be irreplaceable."

There was deathly silence in the Fuehrer's bunker at the Wolfsschanze.

Hitler too was silent. Then he stepped up close to Guderian and in an imploring voice said, "Do you believe Frederick the Great's grenadiers died gladly? And yet the King was justified in demanding of them the sacrifice of their lives. I too consider myself justified in demanding of each German soldier that he should sacrifice his life."

Guderian realized at once that with this bombastic comparison Hitler was merely trying to evade the issue.

What Guderian was talking about was not sacrifice as such, but useless sacrifice.

He therefore said calmly, "Our soldiers have proved that they are prepared to sacrifice their lives. But this sacrifice ought only to be demanded when the end justifies it. And I see no such justification, my Fuehrer!"

From the horrified expressions on the faces of the officers present it was clear that they expected Hitler to explode.

But he did not. He said almost softly, "I know all about your personal effort, and how you lead your troops from in front. But for this reason you are in danger of seeing things too much at close quarters. You are hamstrung by too much compassion for your men. Things look clearer from a greater distance. In order to hold the front no sacrifice can be too great. For if we do not hold it the Armies of Army Group Centre are lost."

The argument continued for several hours. When Guderian left the situation room in the Fuehrer's bunker late at night he overheard Hitler saying to Keitel, "There goes a man whom I have not been able to convince."

That was no more than the truth. Hitler had been unable to convince the man who had molded the German armored forces. To Guderian Hitler's operational principle of holding on at all costs, and, what was more, under the worst possible conditions, was an insult to the traditional and long-tested strategic thinking of the Prussian General Staff. In a hopeless situation one withdraws in order to avoid needless casualties and in order to regain freedom of movement for new operations. One does not hold on merely to be killed.

At the same time one cannot entirely dismiss the argument that permission to retreat in the wastes of the Russian winter and under pressure by a victory-intoxicated and fanatical Red Army might have turned the retreat of the mauled German troops into a rout.

And what would happen once the troops were on the run?

In a retreat panic spreads quickly, turning a withdrawal into disorderly flight. And nothing is more difficult than to halt a flight of panicking units. These considerations had induced Hitler to turn down Guderian's argument with an uncompromising No.

He even countermanded the authorization he had given during the early days of the Soviet offensive for the shortening of frontline sectors and withdrawals to rearward lines, and instead issued his hold-out order which has since been so hotly disputed by military historians : "Commanders and officers must, by way of personal participation in the fighting, compel the troops to offer fanatical resistance in their positions, regardless of enemy break-throughs on the flank or'in the rear. Only after wellprepared shortened rearward positions have been manned by reserves may withdrawal to such positions be considered."

This order has been a subject of contention to this day. On the one side it is said that the order was a piece of lunacy in that it resulted in the substance of the German forces in the East being needlessly sacrificed. The troops, it is argued, would have been quite capable of orderly retreat. Favorable defensive positions, as, for instance, along the high ground of Smolensk, would have compelled the Soviet High Command to launch costly attacks which would have decimated the Soviet divisions instead of the German troops.

No doubt this argument holds good for certain sectors of the front.

But there are also many commanders in the field, General Staff officers and Army Commanders-in-Chief who take the view that a general withdrawal under pressure from the Siberian assault divisions, with their superiority in winter warfare, would have led to chaos at many spots and to the collapse of substantial sectors of the front.

Gaps would have arisen which no commander could have closed again. Holes would have been punched into the line, and the Soviet Armies would have simply raced straight through them, pursuing and overtaking the retreating Germans. And behind Smolensk the Soviets could then have closed the trap round the whole of Army Group Centre.

Perhaps this theory credits the Soviets with rather too much strength and skill.

But it cannot be denied that— from a purely military point of view—Hitler’s simple and Draconic hold-out order probably offered the only real chance of averting the terrible danger of collapse. Subsequent events entirely justified Hitler.

The chronicler concerned only with military history must accept this fact. Political, moral, and philosophical considerations, needless to say, are an entirely different matter. The mental conflicts to which this hold-out order gave rise among commanders in the field, the tragedies it led to, and also the unparalleled heroism and self-sacrifice shown in obeying it are illustrated by the operations of Ninth Army on the northern wing of Army Group Centre, in the Kalinin-Rzhev area, and in the defensive battles of the neighboring Sixteenth Army of Army Group North between Lake Seliger and Lake Ilmen.

Colonel-General Strauss's Ninth Army had been holding the line between the Moscow Sea and Lake Seliger with three Army Corps since the end of October. The line ran from Kalinin to Lake Volgo—the source of the Volga—and like a big barrier blocked the Volga bend, on the southern leg of which was the town of Rzhev. Since mid-December 1941 the Ninth Army had been retreating, step by step, from Kalinin to the south-west. The first attacks by the Soviet Thirty-first and Twenty-ninth Armies were directed against General Wager's XXVII Corps in the area south-east of Kalinin. The temperature was 20 degrees below zero Centigrade. Deep snow covered the frozen ground. Artillery preparation was moderate. Only a few tanks accompanied the Soviet infantry over the ice of the Volga. On the right wing of the Corps, at Lieutenant-General Witthöft's Westphalian 86th Infantry Division on the Volga reservoir, the Soviet infantry attack collapsed in the German machine-gun fire.

In the adjoining sector on the left, held by the Pomeranian 162nd Infantry Division, however, the Russians punched a hole through the line with the aid of a few T-34s, widened their penetration, and struck through with Siberian ski battalions. In spite of this threat, General Förster's VI Corps, on the left of XXVII Corps, held its sector against furious Soviet attacks. In the sector of 26th Infantry Division the combat-tested 39th Infantry Regiment under Colonel Wiese was down to two battalions—3rd Battalion having been divided up in order to replenish the depleted companies— and the similarly weakened Westphalian 6th Infantry Division had to hold a line of 16 miles. But the Russians did not get through. Against the 110th Infantry Division, on the other hand, on the left wing of XXVII Army Corps, the Soviets succeeded in getting across to the southern bank of the Volga. From there they were now threatening VI Corps' only supply route, the road from Staritsa to Kalinin. At the same time the town of Kalinin was beginning to be outflanked. The 3rd Battalion of the Weslphalian 18th Infantry Regiment, the Corps reserve of 6th Infantry Division, was ordered to throw the Russians, who had penetrated with 200 men, back over the Volga again. The Westphalians prepared for action. The thermometer stood at 40 degrees below zero Centigrade. Their line of attack was through knee-deep snow. They tried three times.

But the Russians were across the river in regimental strength.

It was impossible to dislodge them. True, the battalion took 100 prisoners, but it also lost 22 of its own men killed and 45 wounded, and, moreover, had 55 of its men affected by severe frost-bite.

At least they had stopped any further Soviet advance. The important supply road was cleared again and covered, and the threatening encirclement of Kalinin had been prevented. As a result, the Corps gained time to withdraw the units fighting in Kalinin. On 15th December 1941 the town was abandoned.

On 16th December Soviet troops under Generals Shvetsov and Yushkevich moved into Kalinin. The Soviet penetration into the German front on the Volga and the capture of Kalinin were a heavy blow. The eastern wing of Ninth Army had to be taken back. The Soviet High Command had thus gained the prerequisites for striking deep into the flank of the German Army. Colonel-General Strauss had seen the danger approaching. He intended—like Guderian in the south, following Zhukov's breakthrough towards Stalinogorsk—to abandon the front bulge at Kalinin and to swing his Corps back to a greatly shortened line with Lake Seliger as the pivot; the line he intended to hold was a flat arc running from Lake Volgo to Gzhatsk on the Moscow motor highway. Rzhev was to be the centre and the core of the arc. The code name for this winter position was "Königsberg."

The disengagement was to be carried out in small, swift moves through a number of accurately defined intermediate positions, all of them bearing the names of towns as codes— Augsburg, Bremen, Coburg, Dresden, Essen, Frankfurt, Giessen, Hanau, Ilmenau, and Königsberg. However, the timetable functioned only as far as the "Giessen" stop.

There the 'train' came to a halt.

Thanks to the gallantry of the fighting rearguards, the divisions had managed to get as far as "Giessen" more or less intact. In spite of the deep snow they had even managed to take most of their heavy weapons with them. For two weeks they had succeeded in holding off the strong enemy and preserving the cohesion of the front line. The troops accomplished superhuman feats. Frequently the vehicles could be started only after twelve to fifteen hours of extremely hard work. Small fires had to be lit underneath the motor vehicles to thaw out the frozen gear-boxes and transmissions. Even then nearly all the vehicles had to be towed by human labor. Covering lines organized by the fighting formations kept the pursuing Soviets at bay while the rest of the troops got the withdrawal going. The key role was played by individual fighters. In deep snowdrifts they lay behind their machine-guns opposing the furious Soviet attacks. Their thin gloves were not enough to prevent their fingers from freezing off. They therefore wrapped their hands in rags and pieces of cloth. This, of course, made them too clumsy to work the triggers of their machine-guns or machine pistols. They therefore wedged little sticks, twigs, or chips of wood from the charred beams of peasant cottages between the rags enveloping their fists, and with these worked the triggers of their weapons.

Thus the Corps on the right wing of Ninth Army "travelled" via "Augsburg" and "Bremen," "Colburg," "Dresden," "Essen," and "Frankfurt," until Hitler's hold-on order halted their systematic withdrawal long before "Königsberg."

The divisions of 3rd and 4th Panzer Groups had already stopped their withdrawal at the Ruza line. For that reason Ninth Army was now ordered to hold the continuation of this front line as far as the Volga. Field-Marshall von Kluge, the new C-in-C Army Group Centre, demanded strict observation of this order. He instructed Ninth Army: "Everybody must hold on wherever he stands. Anyone failing to do so tears a hole in the line, a hole which can no longer be sealed." The only faint ray of light in the order was the passage: "Disengagement from the enemy can be useful or purposeful only when it results in more favorable fighting conditions, and if possible in the formation of reserves." But the Field-Marshal immediately restricted this concession: "Any disengagement of units from division upward requires my personal authorization."

On 19th December 1941 Colonel-General Strauss arrived at the headquarters of General Schubert's XXIII Corps, which comprised 251st, 256th, 206th, 102nd, and 253rd Infantry Divisions, with a new order: "Not another step back."

Three days later the assault regiments of General Maslennikov's Soviet Thirty-ninth Army struck at the Corps' right wing with T-34s and tried to break through the line of the 256th Infantry Division from Saxony. Maslennikov wanted to reach Rzhev.

The Saxon regiments of 256th Infantry Division resisted desperately. They allowed the Russian tanks to roll past them, and from their holes in the snow shot up the Soviet infantry. Tank demolition squads of the artillery then tackled the T-34s. There was Second Lieutenant Falck of 1st Battalion, 256th Artillery Regiment, lying behind a snowdrift. For camouflage he had slipped on a home-made snow smock. A Soviet tank rumbled past him, spraying the ground with machine-gun fire.

That was Falck's moment.

He leapt at the tank and swung himself up on its stern. Hanging by his fingers, he wriggled round the turret. He pulled the string of two egg-shaped hand-grenades, holding on to the gun-barrel with his right hand. He then leaned well forward and with his left slipped the grenades down the barrel with a vigorous push. He quickly dropped off the tank, into the soft, two-foot-deep snow.

The first bang came at once, followed by a succession of explosions as of fireworks. The hand-grenades had done their job. The tank's ammunition was going up. The line of 256th Infantry Division held on 22nd and 23rd December. It still held on Christmas Eve, and on Christmas Day and Boxing Day. The temperature was 25 to 30 degrees below zero Centigrade, The sky was dark and cloudy, and the ground was shrouded by light flurries of snow. Visibility was less than 100 yards. Out of this backdrop of a "Napoleonic winter" Russian tanks kept emerging like phantoms. German Panzerjägers often engaged the T-34s with their 3.7-cm. anti-tank guns at no more than six yards' range. If the tanks survived, then the antitank gunners were crushed. Frequently the 8-cm. AA combat groups of the Luftwaffe or the explosive charges used by daring individual fighters like Second Lieutenant Falck were the only salvation against T-34s.

By 29th December the men of 256th Infantry Division had been resisting a ten times superior enemy for seven days.

By then they were holding only minor strongpoints— at road-forks, in forest clearings, on the edge of villages. The Russians attacked also in the sector of the neighboring division. Three Armies of Colonel-General Konev's "Kalinin Front" were battering at the German lines along the Volga bend. It was becoming increasingly obvious that Konev intended to strike via Rzhev to the Moscow motor highway, in order to link up with Zhukov's southern prong in the rear of the German Army Group. Rzhev became a keypoint in the destinies of the Eastern Front. By 31st December, the last day of 1941, the main fighting line of 256th Infantry Division had been torn open all over the place, in spite of support by VIII Air Corps. The Russians were infiltrating. The 206th Infantry Division, too, was finished. Its 301st Infantry Regiment was down to a few hundred men. On the same day the cohesion of Ninth Army's line was lost west of Staritsa. In the sector of 26th Infantry Division, north-west of the now burning town of Staritsa, the two battalions of 18th Infantry Regiment and what was left of 84th Infantry Regiment, together with 2nd Battalion of the Divisional Artillery Regiment, were holding out against an enemy coming at them from all directions.

The railway station of Staro-Novoye was also blazing fiercely.

Christmas parcels, special Christmas rations, and the division's winter clothing, which had at long last arrived, were all going up in flames. All the troops were able to save was a dump of Swiss cheese. Everywhere, in all the peasant huts along the sector, there were piles of the large round cheeses. As the relieved men came in from outside they would carve themselves large chunks with their bayonets. But twenty-four hours later the peasant huts and the cheeses had to be abandoned. The regiment had to establish a new switchline against enemy groups which had broken through six miles farther to the south-west, at Klimovo.

Aerial reconnaissance had reported a strong enemy column on the right wing of 256th Infantry Division, outside Mologino. Mologino was 19 miles from Rzhev. And in Rzhev were 3000 wounded.

Division received an order by radio from XXIII Corps to reinforce its right wing and to "hold on at all costs." The remnants of 476th and 481st Infantry Regiments flung themselves into the path of the Russians along the road. Hitler's order "Ninth Army will not retreat another step" nailed down the Corps to the line reached on 3rd January 1942, outside Latoshino, east of Yeltsy.

On 31st December at 1300 hours Colonel-General Strauss had turned up at General Schubert's Corps Headquarters in Rzhev with the order: "Mologino must be defended to the last man."

What other order could he give? Twenty minutes later, at 1325 to be exact, Lieutenant-General Kauffmann, commanding 256th Infantry Division, entered the room. He came straight from Mologino. He was as white as a sheet and half frozen. In a voice trembling with emotion he reported to his Army Commander-in-Chief: "Herr Generaloberst, my division is down to the combat strength of a regiment and is surrounded by Soviet ski troops. The men are at the end of their tether. They are just dropping with fatigue. They flop into the snow and die from exhaustion. What they are expected to do is sheer suicide. The young soldiers are turning on their officers, screaming at them: 'Why don't you just go ahead and kill us—it makes no odds to us who does us in.' Mologino is lost already."

Colonel-General Strauss stood petrified.

Then he said slowly, "It is the Fuehrer's express order that we hold out. There is no other way than to hold on or to die." And turning to General Kauffmann he added, "You'd better drive to the fighting-line, to your men, Herr General—that's where your place is now." The General saluted without a word and left the room.

In point of fact, the situation at Mologino was not quite as desperate as Kauffmann had made out.

In the afternoon of 31st December the remnants of the reinforced 1st Battalion, 476th Infantry Regiment, had been rushed into the town, which was still being stubbornly defended by Reconnaissance Detachment 256 under Major (Reserve) Mummert. The remaining units of the regiment were assigned places in the defensive positions planned west of, the town. However, by nightfall Siberian ski troops had occupied the forest between Mologino and the intended line of defense. What was left to be held?

It was now merely a case of defending Mologino for as long as possible, thereby tying down the Russian forces and preventing them from interfering with the Corps' withdrawal. In fierce fighting the men of the Reconnaissance Detachment and of 1st Battalion repulsed the attacks of the Siberians. Frequently they would hold on to just a few isolated houses in the middle of the township. Then they would gain a little breathing space again by immediate counter-attacks.

Radio communication with Division had been cut off since 2nd January.

Contact with the neighboring unit on the left was maintained by patrols shuttling between them. Nevertheless Major Mummert was determined to hold Mologino. During the night of 2nd/3rd January the signals section succeeded in restoring contact with Division. At Division there was much surprise that Mologino was still being held, and the order was given to evacuate the place at once and to rejoin Division.

Towards 0600 hours Mummert evacuated Mologino. The heavy equipment was left behind. Through the black night and the Siberian lines, moving silently in single file along a trail normally used by patrols, the men made their way to the neighboring unit.

Once more 206th Infantry Division succeeded in sealing the gap torn in the front ot Ninth Army, but on 4th January 1942 the front cracked for good.

Between VI and XXIII Corps a yawning gap appeared, between 9 and 12 miles wide. Through this opening strong Soviet forces now thrust across the Volga. The Soviet Twenty-ninth Army wheeled round towards Rzhev and tried to take the town from the south-west. Major Disselkamp, chief of the supply services of 6th Division, an energetic officer, intercepted the first thrust with hurriedly scraped-together emergency units. These consisted of drivers and other supply personnel, a few self-propelled and antitank guns, units of a repair company, and above all the veterinary surgeons and orderlies of Veterinary Company, 6th Infantry Division. With these men Disselkamp halted the Soviets. In this manner VI Corps was given a chance to establish a new defensive front with 26th and 6th Infantry Divisions. Rzhev was held as a cornerstone for future counteractions. The Soviet Thirty-ninth Army and General Gorin's Soviet Cavalry Corps, however, bypassed the town in the west and drove on southward via Sychevka towards Vyazma.

Although the front was in flames along its entire length, the key sectors and the long-term objectives of the Russians were beginning to emerge clearly.

Colonel-General Konev, having torn a hole in XXIII Corps on the northern wing of Army Group Centre, intended to envelop and wipe out the Ninth Army. On the southern wing Marshal Zhukov was racing through the gap between Second Panzer Army and Fourth Army, aiming at Vyazma, and at the same time hoping to strike at the flank of Second Panzer Army. General Golikov with his Soviet Tenth Army was already encircling the town of Sukhinichi. But General Gilsa's 4000-strong combat group refused to give way and turned the town into a breakwater against the Soviet storm. Gilsa's group held out for four weeks. It was a chapter that will have to be mentioned later.

The year 1941, which had begun with such confidence in victory, drew to its close in an atmosphere of gloom and anxiety.

On Boxing Day Hitler had seized the occasion of a complaint by the new Commander-in-Chief Army Group Centre to rid himself of Guderian, whose constant warnings he had found irksome.

Field-Marshal von Kluge had accused the Colonel-General of disobedience: he had had some major differences with him earlier in December. Hitler thereupon deposed Guderian. The troops in the field were dumbfounded. What was to become of them if they were deprived of the best military brains?

Full of forebodings, Guderian concluded his farewell order to his combat-tested Second Panzer Army: "My thoughts will be with you in your difficult task."

And a difficult task it was. Nowhere could the German Command raise sufficient reserves to halt the Russian penetrations. Red cavalry formations were already pressing against the weak covering lines north of Yukhnov and threatening the vital supply routes to Smolensk. Soviet airborne troops were being put down behind the German lines. The partisans became a major threat. Hitler was ranting against fate, cursing the Russian winter, railing against God and his generals. His wrath fell also upon the well-tried Commander-in-Chief 4th Panzer Group. Early in January, when Colonel-General Hoepner withdrew his 4th Panzer Group—since the New Year raised to Fourth Panzer Army—without, as it was thought at the Fuehrer's Headquarters, asking for permission, Hitler seized on this 'disobedience' in order to make, an example. Hoepner was deposed, degraded, and dismissed the service with ignominy. After Guderian, the troops in the field thus lost their second outstanding tank leader.

That there was no factual justification whatever for this measure is attested by Major-General Negendanck, then signals chief of the Panzer Army, who was a direct witness of the incident.

This is the account he has given to the author:

"A few of us were having lunch with Colonel-General Hoepner, who had just come back from the front. At table he expounded his view to his chief of staff, Colonel Châles de Beaulieu, that the right wing of Fourth Panzer Army should be taken back since the adjoining wing of Fourth Army would not be able to stand up to a Russian thrust into the gap which had arisen there. This view was presently conveyed by telephone to the Chief of Staff of Army Group Centre. We were still at table when Field-Marshal von Kluge rang through to discuss the matter with Colonel-General Hoepner, and I remember clearly how Colonel-General Hoepner repeated at the end of the conversation, 'Very well, then, Herr Feldmarschall, we'll only withdraw the heavy artillery and baggage trains to begin with, to make sure we don't lose them. You will explain to the Fuehrer the need for this measure and request his authorization.' When the colonel-general rejoined us after his conversation he said, 'All right, Beaulieu, you will make all the necessary preparations.' At midnight, suddenly, came the dumbfounding news of Hoepner's dismissal. I was shortly afterwards told by a General Staff officer of Army Group Centre that Field Marshall von Kluge had reported the affair to Hitler not on the lines agreed with Colonel-General Hoepner, but describing the withdrawal of the front as an accomplished fact.

Hitler immediately exploded and ordered the dismissal of our outstanding and universally revered Army commander."

Thus far Major-General Negendanck's report. It represents an exceedingly interesting and valuable contribution to military history, on the much-discussed question of Hoepner's dismissal and on the equivocal role played by Field-Marshal von Kluge in Hoepner's as well as in Guderian's recall from their commands.

Those Marines are way to vulnerable on mainland China. They should be moved to a more secure location. How about the Philippine Islands?

Yes. Even if the Philippines are attacked, they can hold out on Bataan or on Corregidor the 3 months needed to send the relief fleet to set things right. Of course, McArthur will follow the plans, and throw the Nips back at the beaches if they are foolish enough to attack. Manila is every bit as safe as Singapore.

I agree. The Marines stationed at Beijing, Tientsin and Shanghai are far too vulnerable where they are now.

Plan Orange calls for the consolidation of force in the Philippines to center around Bataan. Moving them there will help secure that position and if the Japanese attack, they may get a foot hold on the main island, but we should be able to hold out until reinforcements can be sent.

Recently we have been working hard to increase our bomber force in the Philippines as well so we should be in good shape.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.