Posted on 02/25/2003 2:14:57 PM PST by Lokibob

These three visible images of the orbiting space shuttle Columbia were taken by the U.S. Air Force Maui Optical and Supercomputing Site on January 28 as the spacecraft flew above the island of Maui in the Hawaiian Islands.

|

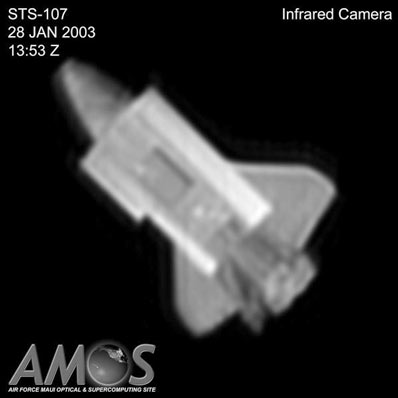

These three infrared images of the orbiting space shuttle Columbia were taken by the U.S. Air Force Maui Optical and Supercomputing Site on January 28 as the spacecraft flew above the island of Maui in the Hawaiian Islands.

|

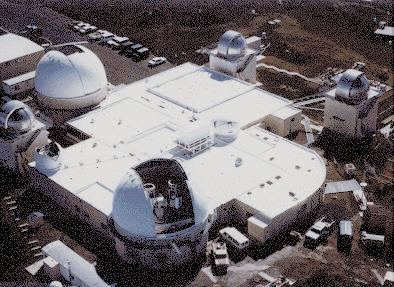

The Air Force Maui Optical Station (AMOS), an asset of the US Air Force Materiel Command's Phillips Laboratory, is located at the summit of Haleakala, on the island of Maui, in the state of Hawaii. It is part of the Maui Space Surveillance Site (MSSS),

The mission of AMOS is to conduct research and development of new and evolving electro-optical sensors, as well as to provide support for operational missions defined by US and AF Space Command. In addition, AMOS provides experiment support to a wide variety of military and civilian organizations in diverse fields. This support has included the Strategic Defense Initiative Organization (SDIO), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), and many universities. AMOS has hosted and supported a wide variety of visiting experiments.

Typical AMOS visiting experiments include:

AMOS telescopes include a 1.6 meter telescope, an 80 centimeter Beam/Director Tracker, and a 60 centimeter Laser Beam Director. MOTIF includes twin 1.2 meter telescopes on a common mount. GEODSS includes two main 1 meter telescopes and an auxiliary 40 centimeter telescope. A major upgrade to AMOS will be the Advanced Electro-Optical System (AEOS), a 3.67 meter telescope scheduled for first light in 1997. AEOS will have seven coude' rooms for various experiments, as well as conventional Cassegrain positions located on the mount itself.

AMOS telescopes include a 1.6 meter telescope, an 80 centimeter Beam/Director Tracker, and a 60 centimeter Laser Beam Director. MOTIF includes twin 1.2 meter telescopes on a common mount. GEODSS includes two main 1 meter telescopes and an auxiliary 40 centimeter telescope. A major upgrade to AMOS will be the Advanced Electro-Optical System (AEOS), a 3.67 meter telescope scheduled for first light in 1997. AEOS will have seven coude' rooms for various experiments, as well as conventional Cassegrain positions located on the mount itself.

Sensors associated with these telescopes include a wide range of detectors and imaging arrays sensitive to the visible and infrared wavelengths. The 1.6 meter telescope has a Compensated Imaging System which has been operational since 1982. The new AEOS will also incorporate an adaptive optics system for atmospheric turbulence compensation. Under development is the AMOS Daytime Optical Near Infrared Imaging System (ADONIS), capable of extending the AMOS imaging capabilities to 24 hours per day. These adaptive optics systems allow AMOS to take photographs of orbiting satellites with outstanding clarity, in spite of the severe problems of dealing with atmospheric turbulence.

Lasers currently available at the site for external propagation include Argon ion lasers, a Neodymium YAG, and a ruby laser. External laser safety is accommodated with the use of plane watch personnel in conjunction with guidelines from the local FAA facility. Predictive avoidance is coordinated with the Laser Clearinghouse to preclude inadvertent illumination of satellites.

In addition to these facilities, the University of New Mexico manages the Phillips Laboratory's Maui High Performance Computing Center (MHPCC). The MHPCC is a state-of-the-art computing center using massively parallel processing computers, based on the IBM SPx series. The MHPCC supports both Department of Defense and civilian users, operating in both classified and unclassified modes. AMOS utilizes the MHPCC for a significant amount of its image processing.

A trick of the light. The left side of the shuttle is in shadow.

I wonder why the detail of the left wing leading edge seems fuzzy?

Tiny Kirtland Telescope Took Critical Shot of Shuttle

By John Fleck

Journal Staff Writer

KIRTLAND AIR FORCE BASE — It was a lark for Rick Cleis and his buddies, the sort of technical challenge the Air Force satellite trackers thrive on.

Could they snap a picture of the space shuttle Columbia as it streaked above Albuquerque on its return to Earth on Feb. 1?

NASA didn't ask for the picture. The researchers just thought it would be fun.

Rigging up a small home telescope, a decades-old satellite-tracking mirror array and an ancient Macintosh computer, they succeeded historically.

As dawn broke, Columbia appeared above high western clouds, right where the NASA flight track said it would be, and they snapped a single grainy picture.

That ghostly image, released last week by NASA, is the last close-up image before Columbia broke up in the skies above Texas, killing the seven astronauts aboard.

Some observers suggest it shows damage to Columbia's troubled left wing. NASA is not so sure.

"It's not clear to me that it reveals anything significant at this point," said shuttle program manager Ron Dittemore during a news briefing last week.

After almost two weeks of official silence, Air Force and NASA officials Wednesday allowed the team that snapped the picture to talk about how they did it.

Cleis, Robert Johnson and Roger Petty work at the Air Force's Starfire Optical Range, using telescopes to track and study satellites in orbit.

That led to speculation that the picture had been taken with the Air Force's most powerful satellite-tracking telescope. In interviews Wednesday, they tried to set the record straight.

It was just some guys cobbling together cheap old gear for fun, they said.

The shuttle's orbit only rarely carries it over Albuquerque, and the Starfire team doesn't often get the chance to track objects re-entering Earth's atmosphere, said Johnson, an Air Force major.

They got the data they needed from NASA to track the shuttle as it passed, but they were too busy with their regular work to get started setting up for the attempt until the night before.

"We literally started that Friday evening," Cleis said. Johnson worked until 10 p.m., aligning a little old Questar telescope they pulled out of a closet for the task. Cleis — whose colleagues call him "the telescope wizard" — stayed up all night writing the software to track the descending shuttle.

They have some of the most powerful telescopes available for the job, including a behemoth with a mirrored lens more than 11 feet in diameter. But for their Feb. 1 attempt, they chose the smallest telescope in their arsenal. It was the easiest to set up for the unique job of tracking the fast-moving shuttle, flying far lower than their usual targets, they said.

The Questar is small, even by the standards of backyard astronomy. Its lens is just 3-1/2 inches in diameter.

They mounted it in front of a set of larger movable satellite-tracking mirrors that had been salvaged from White Sands Missile Range two decades ago.

Old but still reliable, the mirrors tracked the shuttle, reflecting its image back to an instrument room where the telescope was mounted.

From the time Columbia emerged from clouds in the west until they lost it because of clouds in the east, the shuttle was only visible for 24 seconds, according to Robert Fugate, Starfire's chief scientist.

That was only enough time to snap one picture. The shuttle was 36 degrees above the western horizon, nearly 70 miles away at the time.

It was not long before they got a telephone call in the control room from a family member, telling them that the shuttle had broken up.

They immediately grasped the significance, and made backup copies of the computerized image.

"We said, 'We'd better start backing this up, somebody's going to want to see this,' '' Johnson said.

The image was turned over to NASA, which is still analyzing it as part of its investigation.

A trick of the light. The left side of the shuttle is in shadow.

The visible light pics have us looking at the "top" of the shuttle, and I think the IR pics have us looking at the "top" again.

If that's true, looking for symmetry in each set of pictures seems to indicate that the left wing leading edge is missing.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.