Posted on 05/11/2020 8:45:29 AM PDT by Kaslin

Inherent limitations of the tests we currently have make it unlikely that applying testing to the entire population is going to be very useful.

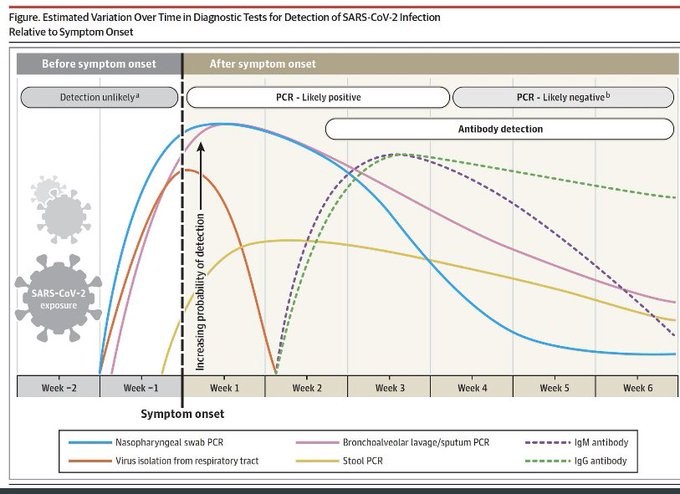

At the moment there are two types of tests: real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and serologic testing. RT-PCR detects the virus’s genetic code, while serologic testing detects antibodies the body makes in response to the virus. Both forms of testing have limitations that are important to consider when trying to evaluate the accuracy of tests.

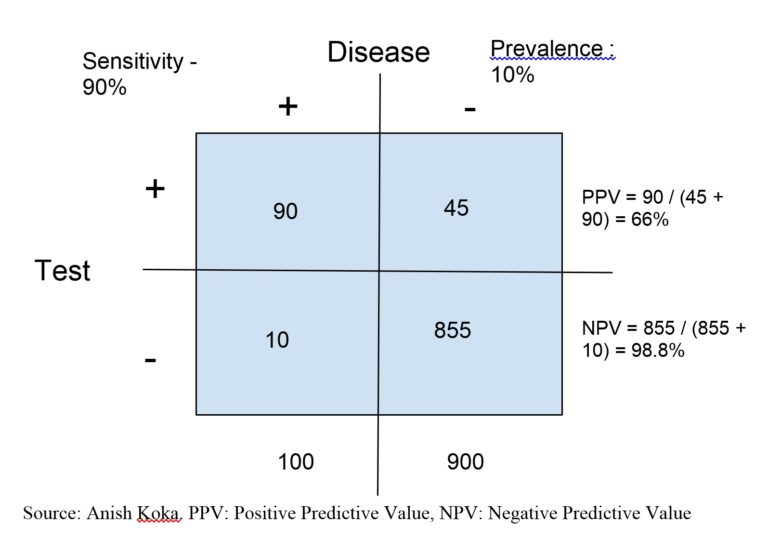

Diagnostic tests have traditionally been evaluated based on sensitivity and specificity. Sensitivity refers to the probability a test will return a positive result in someone who has the disease being tested for, while specificity refers to the probability a test will return a negative result in someone who does not have the disease being tested for.

A poorly sensitive test will miss a lot of people who actually have a disease, while a poorly specific test will say a lot of patients have a disease when they actually don’t. So a very accurate test should have a high degree of sensitivity as well as specificity.

Yet even a test that appears to be very good by these metrics may end up being almost useless because test performance is highly dependent on the underlying suspicion of disease. This is mostly why doctors don’t recommend getting tested for everything just because you can. Even cancer screenings are targeted to try to ensure the screened population is at higher risk of disease because there may be more harm than good if 20-year-olds were to start getting mammograms en masse.

Understanding why requires understanding that sensitivity and specificity, while important, are less important to patients than predictive values. Patients want to know the probability they have a disease if their test is positive or negative. Sensitivity and specificity are simple probabilities that tell you how the test performs in people whose disease status is already known. Converting these numbers to predictive values requires knowing the underlying prevalence of the disease in the population being tested.

As an example, let’s imagine an island of 1,000 individuals with a prevalence of lupus of 1 percent. This means 100 patients have lupus on the island (0.01 x 1,000). If we use the sensitivity and specificity from above (90 percent sensitive, 95 percent specific), 90 of the 100 patients are true positives, and 855 (0.95 x 900) patients are true negatives. This leaves 10 false negatives, and 45 false positives.

This means that this particular test will have 135 positive tests. But only 90 will be truly positive, the remaining 45 are false positives, which gives a 66 percent chance that a positive test means actually having the disease. Uninspiring probabilities, to say the least.

The situation can be improved markedly by greatly improving how specific a test is to reduce the number of false positives, but even a test that is 99 percent specific requires a prevalence of disease more than 10 percent for the test result to be meaningful.

The problem for coronavirus testing is that it is likely circulating in most places in the United States in very small single-digit numbers, except for a small number of ZIP codes located in a few hotspots in the country like certain counties in New York, New Jersey, and Michigan.

Our current testing does include RT-PCR, which is nearly 100 percent specific. This means everyone who tests positive with this test has the virus, but unfortunately the test has been found to have a high rate of false negatives, so a negative test doesn’t rule out disease.

PCR also only speaks to disease status at the time of the test. It’s possible a PCR-negative patients acquires the virus the following day. Complicating matters even further is that we may shed viral RNA that PCR can detect for up to six weeks after an infection, although it is definitely not the case that this means people are infectious for six weeks.

Antibody tests to date have not been robustly validated in part because this is hard to do. Finding true positive and negative controls is challenging. Antibody tests are also negative early in the course of disease because the body has not had time to produce enough detectable antibody, and may be falsely positive if they crossreact with other commonly circulating coronaviruses that are known to cause the common cold.

So inherent limitations of the tests we currently have make it unlikely that applying testing to the entire population is going to be very useful. Testing for high-risk patients like health-care workers and symptomatic patients is important, not because it will be perfect for the individual patients, but because it can track outbreaks of disease in the population.

These considerations make it even harder to understand how test-based contact tracing and isolation will be effective. If we test too broad of a population, we are likely to make life unnecessarily difficult for a vast number of Americans who would face the risk of isolation based on an inaccurate test, and spend vast public health resources doing contact tracing for no good reason.

Even if the tests performed much better than they do currently, the architecture that is being discussed to do contact tracing has major unresolved issues. The cool-sounding idea is to use smartphones to track who citizens come into contact with. Theoretically, once a patient tests positive, a list of other phones and citizens the patient came into contact with over the prior 48 hours could easily be tracked.

Practically speaking, this would require a large proportion of patients (upward of 60 percent) in a population to download and use the app, and there would be a high probability of false positives generated by phones that ping each other through walls or ping the runner jogging by you in the park six feet away. It’s also notable that Singapore, a very small country with a population of 5 million, is in the midst of a significant outbreak that forced a widespread lockdown despite its widely praised app-based contact tracing.

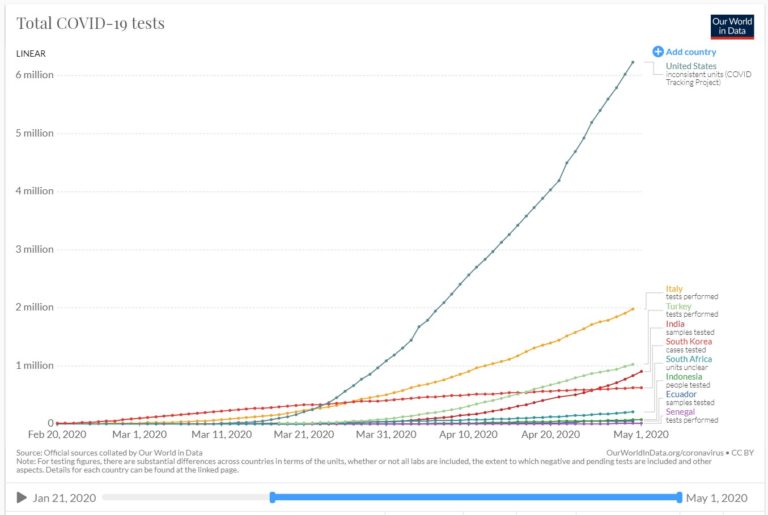

Much of the enthusiasm to test more comes from those that link countries with high testing rates to low death rates. In doing so, proponents conveniently ignore that the various countries also differ in size, density, geographic location, population demography, connectedness, and travel/social distancing policies.

Also ignored is the amount of testing currently taking place in the United States. New York is testing at a rate five times higher than South Korea. At the moment, testing capacity in most of the country actually exceeds the demand for testing.

Testing is vital to tracking outbreaks in communities and informing policy locally and nationally, but it is profoundly unclear that reaching some magic higher threshold of testing is the answer to our problems.

But tracking will help a lot supposedly right? How will they know who had it or has it? How will they input that data? It sounds like they are making the assumption that everyone has a cell phone attached at the hip. Mine will be spending a lot more time at home all lonely and stuff. Are HIPPA laws now cast aside?

Testing and tracking are red herrings, that if attainable at all, will take months and stretch the shutdown till at least the election. Of course, that is the real goal.

This is a red herring......talking point to bash the President....unless everyone get tested everyday it won’t matter.....

.unless everyone get tested everyday it won’t matter.....

add at the same moment.

1 percent of 1,000 is 10, not 100.

Thank you very much for posting this.

Too many people are jumping on the bandwagon that serological (antibody) testing is showing that Covid-19 is already widespread, because that bandwagon supports a narrative. I have been trying to talk that down, with variable levels of success.

This article explains why antibody testing is not reliable. This has nothing to do with the reputability of the company making the tests, but with the biochemistry of antibodies.

There are a lot of limitations to various kinds of testing. When I post explanations about testing, I don’t even try to discuss all of the limitations. I’m trying to make forum posts, not in-depth 5000 word articles.

I’m reading this. And the author is babbling. Not getting to any point. I’m wondering when the payoff will come.

Then I read

“As an example, let’s imagine an island of 1,000 individuals with a prevalence of lupus of 1 percent. This means 100 patients have lupus on the island ...”

1% of 1000 is ten.

“As an example, let’s imagine an island of 1,000 individuals with a prevalence of lupus of 1 percent. This means 100 patients have lupus on the island (0.01 x 1,000).”

Quit reading right there. If the author can’t do simple arithmetic...

Well, since I don’t feel like I have any of the symptoms, why would I waste time getting tested? No current plans to be tested. When will someone that stands to make a LOT of money submit a bill to make testing mandatory? Surely there are at least a few folks in CONgress that have some CONnections to big pharma.

This is nonsense. If I, and others I know could get a serum antibody test, those of us that tested positive would go back to life as normal - including work and opening businesses back up.

It doesn’t even rise to the level of nonsense.

This author couldn’t even knock over his own strawman.

Why The Federalist would publish it is a mystery.

If you tested positive you would act like as if nothing was wrong? Sorry but that doesn’t make any sense to me. Maybe I misunderstand you.

Combine 3 factors:

1. This evidence of false positives

2. The left’s insistence on forcibly ramping up testing

3. The drop off in daily case confirmations

At some point we will be destroying our society to try and cure nothing but non-existent cases.

I know I don’t have any symptoms as I haven’t been anywhere where I can get the symptoms. So that settles it for me.

“If you tested positive you would act like as if nothing was wrong? Sorry but that doesn’t make any sense to me. Maybe I misunderstand you.”

Yeah.

He was talking about testing positive for the antibodies meaning you already had it and are over it.

Eight years of 0bama really screwed up the societal use of Zer0.

You misunderstand, that is a fact. If you test positive for antibodies, that means that your immune system has encountered the virus before and learned how to deal with it. This means that there is no chance that you will contract the disease in question, because you are already immune. Vaccinations work on the same principle: you introduce a pathogen and allow the person’s immune system to learn about it. The antigen usually is attenuated, which means it is not active.

If I were to test positive for the antibody I would not only act as if nothing was wrong, I would celebrate, probably with gin and tonic. I wonder what you would say that would make it clear that this would not be the correct action. I trhink you are on the side of this is a plague that will kill millions if we don’t act now, although now has been the last THREE FREAKING MONTHS.

You might have a weak and pathetic immune system that isn’t up to the task of producing antibodies. I however have a strong and powerful immune system that laughs at your flacid immune system that will let you die of a cold. My immune system can beat your immune system any day.

Yes, if I tested positive for antibodies, it would be business as usual for me. And, for everyone else I know. We need antibody testing.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.