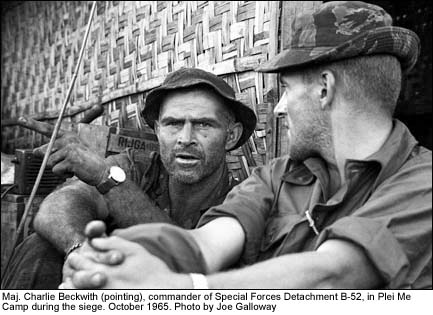

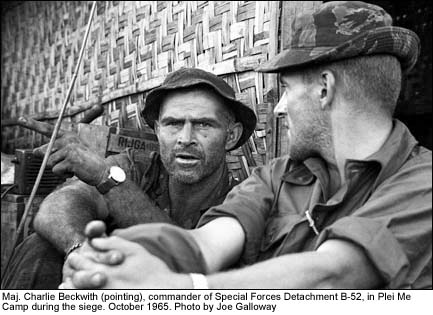

Straight lines, square corners, yes, sir, no, sir, three bags full. That's what I'd been taught. That's what I knew. I was a captain in the United States Army. Straight lines. Square corners. Yes, sir! No, sir! Three bags full!

I walked into Three Troop's wooden barracks. The long room was a mess. It was worn and dirty. Rucksacks (called Bergens) were strewn everywhere. Beds were unkemt, uniforms scruffy. It reminded me more of a football locker room than an army barracks. Two of the troopers -- I never learned if it was done for my benefit or not -- were brewing tea on the floor in the middle of the room.

I commented on the state of the room and on the men. I added, "What we need to do is get this area mopped down, the equipment cleaned, straightened, and stored, and the tea brewed outside." Two troopers, Scott and Larson, spoke up at once. "No, sir. that's not what we want to do. Otherwise, we might as well go back to our regular regiments. One of the reasons we volunteered for the SAS was so we wouldn't have to worry about unimportant things." I didn't understand that. I thought I'd been given a group of roughnecks to command. Also, I suspected the troops were not comfortable with me. Who was this bloody Yank who didn't understand at all about freebooting behavior in a special opeations unit? But I felt I had to bring the troop into line. My job, as I saw it, was to get them dressed smartly and to make parade soldiers out of them. Yes, sir! That was my job. I went home that night and told Katherine I felt I might not be able to handle this.

Peter Walter, my squadron commander, would normally have an officer's call at the end of each day. I found that whenever one of the officers addressed Major Walter he'd use his first name, and Major Walter, at his turn, would use the troop commander's first name. When I asked a question, I would address my commanding officer as Major Walter. This went on for several days and finally Major Walter called me in. "Let me explain the form." In a very precise and penetrating voice he told me that in the SAS system when an officer was in the midst of troopers or standing in a formation with what the Brits call ORs (Other Ranks), noncommissioned officers and enlisted men, they addressed each other using their ranks. "But, when we're in a room like this and there are just officers present it's always on a first-name basis. And that's the way I want it to be. Do you understand?" And I said, "Yes, sir!" "There you go again," he replied. That really made me uncomfortable.

I couldn't make heads or tails of this situation. The officers were so professional, so well read, so articulate, so experienced. Why were they serving with this organization of non-regimented and apparently poorly disciplined troops? The troops resembled no military organization I had ever known. I'm sure if I had been put in with a unit of the Coldstream Guards or the Household Cavalry I would have known what to expect. But the 22 Special Air Service Regiment! Well, this was too different, and for me th eimpact was too soon. I was adrift in a world that I thought I knew. I couldn't predict what would happen next in any given situation. Everything I'd been taught about soldiering, been trained to believe, was turned upside down. -- Charlie Beckwith

From Delta Force