|

Posted on 09/24/2003 12:00:22 AM PDT by SAMWolf

|

|

are acknowledged, affirmed and commemorated.

|

| Our Mission: The FReeper Foxhole is dedicated to Veterans of our Nation's military forces and to others who are affected in their relationships with Veterans.

Where the Freeper Foxhole introduces a different veteran each Wednesday. The "ordinary" Soldier, Sailor, Airman or Marine who participated in the events in our Country's history. We hope to present events as seen through their eyes. To give you a glimpse into the life of those who sacrificed for all of us - Our Veterans.

|

|

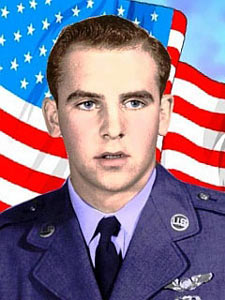

April 10-12, 1966 The sandy beaches at the South Vietnamese resort town of Vung Tau quickly give way to dense jungle as one moves westward towards Saigon. Here the jungle grows in layers, often triple-canopy (3-layers) of heavy vegetation. So thick is the top layer, often rising over 150 feet upwards, that sunlight never reaches the vegetation at ground level. During the brightest day, soldiers moving across the jungle floor can almost feel that they are moving about at night.  Staff Sergeant James Robinson, a former Marine, had volunteered for Vietnam duty...had in fact, engaged in a determined year-long letter writing campaign from his duty station in Panama in efforts to be assigned as an advisor to soldiers of the Vietnamese Army. Sergeant Robinson believed strongly in the U.S. role in Vietnam, telling his father in one letter: "There's a world on fire and we should do something about it." Now, as he lead his fire-team through the dense jungles of Phuoc Tuy province, he recalled what he had written home in his most recent letter..."The price we pay for freedom is never cheap." Little did he know how expensive that price was about to become. The first explosion came from American artillery fired in support of Operation Abilene. One round fell short, detonating in the top of the jungle canopy and raining deadly shrapnel on Sergeant Robinson's platoon. Two men were killed, twelve wounded, and the tall sergeant from Cicero, Illinois set his men to the task of clearing a landing zone for medevac choppers to extract the casualties. As the survivors hacked through the jungle vegetation, they did not realize they were only yards from their primary objective...the command post of the Viet Cong Battalion Operation Abilene sought to find and destroy. As the infantrymen fought to reclaim enough jungle landscape for the medevacs to land, the enemy attacked with mortars and machinegun fire. Pandemonium erupted among the American soldiers as they clammored for any semblance of shelter. In the midst of sudden death and unrestrained terror, Sergeant Robinson began moving among the men to organize defensive fire and inspire confidence. Locating one highly effective enemy sniper, Robinson used a grenade launcher to end the threat. In the distance he could see an Army medic kneeling to bandage the wounds of a wounded American infantryman. Enemy fire reached out to tear flesh and the medic fell to the ground. Realizing the two wounded men were dangerously exposed to continued enemy fire, Robinson ignored the whine of deadly missiles around him to rush into the open and drag the two wounded men to safety.  Staff Sergeant James Robinson As the fighting continued to escalate, more wounded fell. Sergeant Robinson noticed another American fall ahead of his position. Rushing forward to rescue the wounded man, enemy rounds slammed into Robinson's shoulder and leg. Ignoring the pain, he dragged the wounded man to shelter, administered life-saving first aid, and then treated his own serious wounds. While patching up his broken body he noticed the location of an enemy machinegun that had been inflicting heavy casualties on his unit. His rifle empty, Sergeant Robinson again ignored his wounds to attack. Another Viet Cong bullet hit the intrepid soldier in the leg. The round was a tracer, igniting the trousers of his jungle fatigues. Sergeant Robinson ripped the burning uniform from his body and continued forward. At six-feet, three inches tall he was an inspiring sight for the beleagured men of his platoon. He was also a very large target. The full force of the agressors turned their firepower on the advancing American. Two more rounds struck flesh, ripping into Sergeant Robinson's chest and draining what little strength remained in his broken body. Somehow, through sheer force of determination, he continued forward...falling only after reaching effective range and throwing the two grenades to destroy the enemy position. The price Sergeant Robinson paid for freedom wasn't cheap...he purchased it with his own life.  The worst was yet to come for Charlie Company. Normally the unit consisted of four platoons of 291 men but, going into Operation Abilene, company strength was down to 134 soldiers. These men were now cut off from Able and Bravo companies, and were surrounded by 400 or more enemy soldiers. Hidden by the dense jungle, the enemy was able to hide and still place effective sniper fire on the Americans. Quickly the attack escalated to intense mortar and machinegun fire throughout the entire area. Dead and wounded American boys littered the undergrowth in what was quickly becoming a massacre. Because of the thick, triple-canopy jungle, Army medevacs could not come in to retrieve the wounded...there was simply no place to land. The nearest clearing was 4 miles away. The only hope of getting the wounded out and headed for emergency field hospitals lay with the Air Force Huskies that were capable of hovering above the canopy to lower an empty stokes litter, then winch it back up with the body of a wounded strapped inside.  At 3 o'clock on the afternoon of April 11th, the call for help arrived at the headquarters of the 38th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron at Bien Hoa. Two Air Force Huskies were quickly airborne and moving east to find and extract the wounded soldiers of Charlie Company. Captain Ronald Bachman piloted the primary HH-43, call sign "Pedro 97". Captain Harold Salem piloted the back-up aircraft, "Pedro 73". Behind the pilot and co-pilot in Pedro 73, was Airman William Pitsenbarger. His only remark when the call for help arrived had been, "I have a bad feeling about this mission." It was the first time the pararescueman had ever voiced any misgivings about any mission. By 3:30 the two Air Force choppers were hovering over the tops of the jungle canopy while death and devastation raged below. Pedro 97 went in first, lowering the stokes litter to retrieve one of the wounded. Then Captain Bachman pulled back a short distance to transfer the patient to a folding litter while Pedro 73 went in to pick up a second wounded soldier. That done, Captain Bachman returned to use the stokes to pull one more wounded soldier from the field of battle. The two Huskies then turned towards the field aid station 7 miles away near the village of Binh Ba. While the three initial recovered casualties were unloaded, Pits and Pedro 97's PJ Sergeant David Milsten discussed "going in" on the choppers' return.  The choppers could only carry two stokes litter patients on each in-and-out, and only one if there was no PJ aboard. Ambulatory casualties could be hoisted to the waiting choppers on "jungle penetrators". This cable contained 3 spring loaded seats that could be dropped through the heavy canopy to pull up men capable of riding the hoist up. Usually when a PJ "went in", he rode the penetrator down to either load a casualty in the stokes litter or aid two casualties in riding the penatrator. With the three-seat penatrator, a PJ could send up three wounded, then ride back up to his Huskie with two more wounded on a second lift. This allowed the rescue team to recover 4-5 wounded men with each in and out trip of the helicopters. On the ground things had gone from bad to worse. Army Sergeant Fred Navarro of Hutchins, Kansas was a squad leader in Charlie 2/16th. Seven of his 10-man squad had already been killed in action. Navarro himself was wounded. Nearby Lieutenant Johnny Libs was doing his best to bring some semblance of order to what remained of his platoon. Dead and dying were everywhere and panic was pushing his young soldiers beyond reason. Then, over the cries of the wounded, he heard the sound of a returning rescue helicopter. Moments later a stokes litter was being lowered to the ground. Still taking fire, the infantrymen were struggling between survival and attempts to load a wounded man in the litter. From above Airman Pitsenbarger watched them struggle with the apparatus. He turned to Captain Salem at the controls and said, "I'm going in." The captain consented and slowly the choppers crew chief Airman First Class Gerald Hammond lowered his friend on the jungle penetrator. Totally exposed at the end of the cable, enemy rounds sang past the gallant PJ as he voluntarily rode the penetrator into a nightmare beyond human comprehension.  Lieutenant Libs strained his eyes against the unexpected sight. He turned to his machinegunner and said, "That guy coming out of the helicopter from above, in an Air Force uniform, must be out of his mind to leave his not-so-safe helicopter for the inferno on the ground." Days later in restrospect he added, "We were in the fight of our lives, and I just couldn't understand why anybody would put himself in this grave danger if he didn't have to." When the young PJs feet touched ground, he went into immediate action. His experience expedited the process of getting the wounded soldier into the stokes litter and a fourth casualty was being hauled skyward. Once the man was airborne the crew of Pedro 73 expected their pararescueman to ride the penetrator back up to his waiting chopper. Instead, Airman Pitsenbarger waved them off, electing to remain with the soldiers on the ground. Without their PJ aboard, the chopper could only carry out one stokes patient, so Pedro 73 headed back to Binh Ba. As Captain Salem headed towards the aid station, Pedro 97 moved in to hover over the battlefield. Under the guidance of the brave PJ, the infantrymen were able to quickly send two more stokes patients to safety. The rescue effort took on new efficiency with an experienced man on the ground. In little more than an hour the two birds had each made two in-and-out trips to recover six wounded soldiers. After unloading at Binh Ba, Pedro 73 diverted to refuel while Captain Bachman and Pedro 97 returned for the fifth pick-up of the day. This time, working in tandem with Sergeant Milsten on Pedro 97, Pitsenbarger was able to load one litter case and two more wounded on the penetrator. Nine men out and Captain Salem was returning for more as Pedro 97 headed for Binh Ba with their heaviest load of the day.  As Captain Salem hovered, the Airman Hammond began lowering the stokes from Pedro 73. On the ground Pits signaled for the penetrator. Since the litter was already outside the helicopter, Hammond placed the penetrator inside the stokes and began lowering both. The package was about 10 feet off the ground and Pits was reaching upwards to receive it when a flurry of enemy .30 caliber rounds from two separate positions, raked the hovering rescue helicopter. At least nine rounds hit the aircraft, one of them tearing through the wiring and causing the throttle control to jam at full-throttle. The power and rpm shot over the red lines and the helicopter lurched forward and up...out of control. The stokes litter dragged through the trees as Captain Salem fought for control. Among other problems, he had also lost partial rudder control. The dragging litter threatened to snag in the foilage and bring Pedro 73 crashing to the ground. Quickly the pilot threw the switches to arm the cable cutter, releasing the litter and freeing his aircraft. As Salem fought to save his Huskie, his departure left the valiant PJ stranded on the ground with Sergeant Navarro, Lieutenant Libs, and the few survivors of Charlie Company.  Airman William Pitsenbarger William Pitsenbarger loved his job. An adventurer since boyhood, his greatest thrill had always been the opportunity to save lives. His medical training had served him well, so well in fact, that he had applied to Arizona State University to study to become a medical technician or male nurse upon completion of his Air Force tour of duty a couple months hence. Now, stranded on the ground with the few survivors of Charlie Company, he took little time to ponder the predicament into which he had voluntarily placed himself. Even as enemy fire continued to scorch the area, he moved among the casualties to tend the wounded and administer life-saving medical attention. When he found the bodies of American boys that could not be saved, he gathered weapons and ammunition to distribute among those who could still fight. Finding one wounded infantryman, injured beyond ability to fire a rifle, Pits gave the soldier his own pistol to enable him to continue to resist. He was one of the few calm visions of hope that moved among the damned. How bad was it on the ground? One of the few survivors, Army Lieutenant Martin Kroah later said, "At times, the small; arms fire would be so intense that it was deafening, and all a person could do was get as close to the ground as possible and pray. It was on those occasions I saw Airman Pitsenbarger moving around and pulling wounded men out of the line of fire and then bandaging their wounds. My own platoon medic, who was later killed, was totally ineffective. He was frozen with fear, unable to move. The firing was so intense that a fire team leader in my platoon curled up in a fetal position and sobbed uncontrollably. He had been in combat in both World War II and Korea."  One can not judge the young men who reacted to the horrible events of April 11th with fear and panic. Ranging in age from 19-21, most had never witnessed such horror first hand. One must imagine William Pitsenbarger must have felt fear himself. No sane man could live through such a nightmare without such emotion. But what made the young pararescueman from Piqua, Ohio stand out was how he dealt with fear. His decisions were deliberate, calculated, and carried out with the highest degree of professionalism. Pits expected the Air Force Huskies, or at least Pedro 97, to return for more wounded. He noticed the stokes litter caught high in the jungle canopy. Despite the continuing enemy fire, he climbed the trees to salvage the litter and make it ready for the choppers' return. Indeed, after escorting the badly damaged Pedro 73 to an emergency landing, Captain Bachman and his team returned. By this time the Viet Cong were lobbing mortars into the area, and American forces responded by dropping artillery rounds in and around the small perimeter the survivors of Charlie Company were trying to create. Pedro 97 hovered in the area as darkness fell, then returned to Bien Hoa to wait out the night.  In the hour and a half Pits was on the ground, he was everywhere. When the company was ordered to move a short distance the intrepid Airman began cutting branches to improvise litters to transport the wounded. As darkness began to fall he disappeared for about 10 minutes, returning to the area receiving the heaviest enemy fire with 20 or more magazines of ammunition he had scrounged from among the dead. Next to him the wounded Sergeant Navarro was struggling to stay alive, and to resist. Quickly the total darkness of the jungle night was falling across the area as the two men lay in their position returning fire on the enemy. It was nearing 7:30 in the evening as the enemy fire was beginning to taper off. Sporadic rounds continued to whistle through the air around Sergeant Navarro, but with the encroaching darkness there was coming an eerie quiet as well. Next to him, all was quiet. No longer could he hear the sounds of William Pitsenbarger's M-16. Even without looking the young infantry sergeant knew what had happened. William Pitsenbarger was dead. Within days of that horrible night, Sergeant Fred Navarro provided the Air Force with a taped statement detailing the heroism of Airman First Class William Pitsenbarger in support of a recommendation for the Medal of Honor. Few witnesses remained of the young PJs service and sacrifice. Of the 134 soldiers in Charlie Company at the beginning of Operation Abilene, there were 106 casualties. Only two members of Sergeant Navarro's 10-man squad had survived.  Army Staff Sergeant James Robinson was submitted for the Medal of Honor for his heroic sacrifice during Operation Abilene. His posthumous award was presented to his father at the Pentagon in ceremonies on July 16, 1967. The recommendation for William Pitsenbarger's Medal of Honor was downgraded to the Air Force Cross. When Mr. and Mrs. Pitsenbarger accepted that award on behalf of their heroic son on September 22, 1966, William Pits Pitsenbarger became the first enlisted airman in history to receive the Air Force's second highest award for military heroism, posthumously.

|

As is expected. I wouldn't have it any other way. ;)

The media are determined to turn the victory in Iraq into a failure.

Perception is reality.

A congressman (can't remember his name) was on Greg Garrsion's show last week, and he wanted to know what country the media was reporting about, because it sure wasn't the same Iraq he just returned from.

I know what you mean. It's difficult for me to put my thoughts into words after reading about sacrifices such as these. You are right though, we come away from the Foxhole knowing the spirit of all these Americans, generation after generation. God bless them all.

They're reporting from "Anything that makes Bush look bad Country"

As long as we continue to do that, our freedom should be secure.

For such a small service, the Air Force spec ops types have produced some very gallant heroes.

"09/16/02 - KIRTLAND AIR FORCE BASE, N.M. (AFPN) -- Senior Airman Jason D. Cunningham, a pararescueman who lost his life in Afghanistan while saving 10 lives and making it possible for seven others who were killed to come home, was posthumously awarded the Air Force Cross here Sept. 13."

Cunningham, based at Moody Air Force Base in Valdosta, Ga., was one of eight soldiers from three services killed during an assault on an 11,000-foot-high mountain redoubt near the town of Gardez in eastern Afghanistan.

Maj. Vincent Savino, commander of the Air Force's 38th Rescue Squadron that Cunningham was attached to, gave new details of the engagement that became America's bloodiest battle to date in Afghanistan.

Cunningham was part of a quick-reaction force sent to rescue a group of soldiers pinned down by heavy machine-gun and rocket fire on a mountain slope. One helicopter had already been shot down when Cunningham's unit flew in aboard another.

"They went in under heavy machine-gun fire. The helicopter was hit by a rocket and crash-landed," Savino told the hushed church. "The pilot and co-pilot were wounded. Some of the Rangers on board had been shot."

Cunningham, a paramedic, opened his rucksack and began treating the wounded. But the flames and smoke from the burning MH-47 helicopter forced him and another rescuer to move the wounded soldiers outside. As they maneuvered over the rocky terrain, gunfire and mortar shells rained down from entrenched Al Qaeda and Taliban positions above.

"Jason said they had to get these guys out of there. He ran across a direct line of fire to move the wounded men to another location," Savino said.

He helped move the wounded three times to shield them from enemy fire.

"Jason was going back and forth treating his wounded comrades when he was shot," Savino said. "He was shot but he continued to treat 10 wounded patients. They owe him their lives. The only reason they came home was because of Jason Cunningham. It doesn't make it easier saying he died doing what he loved or that he was a hero, but that's what he was."

Another Californian, U.S. Navy SEAL Neil Roberts of Woodland, also died in the fight.

Before the battle of March 4 and 5, Cunningham had helped rescue eight crew members aboard a C-130 transport plane that had crashed in Afghanistan. He wrote his wife the letter she had earlier read after that experience.

"He'd seen the dangers of what happened there and he was afraid," she said.

A month before his deployment in Afghanistan, Cunningham and his wife saw the film "Black Hawk Down" about a fierce battle between U.S. Army Rangers and Somali gunmen in Mogadishu.

She asked him why it was necessary for 10 men to go back to save one or retrieve a dead comrade.

"He said, 'Wouldn't you want someone to come after me? Those Rangers and pilots can do their jobs because they know someone is coming after them,'" she recalled.

Rest in peace, Airman Cunningham. You have the gratitude and prayers of a grateful nation, and especially the men whose lives you saved.

|

Homecoming

LTC Parkhurst, Aviation Brigade, shakes the hand of a soldier from the 3rd Infantry Division (M), Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 1st Battalion, 3rd Aviation Regiment, who has been redeployed to Fort Stewart from Operation Iraqi Freedom. DoD Photo by Catherine D. Johnson  Soldiers of the 3rd Infantry Division, Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 1st Battalion, 3rd Aviation Regiment, walk across the tarmac and descend the stairwell of the commercial aircraft that brought them home, from Operation Iraqi Freedom to Fort Stewart, Ga.Defense Dept. photo by Catherine D. Johnson  Lt. Col. Parkhurst, Aviation Brigade, gets a big hug from a soldier of the 3rd Infantry Division, Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 1st Battalion, 3rd Aviation Regiment, during redeployment to Fort Stewart, Ga. from Operation Iraqi Freedom.Defense Dept. photo by Catherine D. Johnson  Chaplain (Maj.) Foxworth greets Lt. Col. Williams as the 3rd Infantry Division, Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 1st Battalion, 3rd Aviation Regiment redeploys to Fort Stewart, Ga. from Operation Iraqi Freedom.Defense Dept. photo by Catherine D. Johnson  Welcome back posters for soldiers and units cover the wall as an Army band and family and friends wait for the return of the 3rd Infantry Division, Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 1st Battalion, 3rd Aviation Regiment, to Fort Stewart, Ga. from Operation Iraqi Freedom.Defense Dept. photo by Catherine D. Johnson  A soldier from the 3rd Infantry Division, Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 1st Battalion, 3rd Aviation Regiment, is thrilled to be reunited with his children again. The soldier is being redeployed to Fort Stewart, Ga. from Operation Iraqi Freedom.Defense Dept. photo by Catherine D. Johnson  Chaplain (Capt.) Hammil of the 3rd Infantry Division, Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 1st Battalion, 3rd Aviation Regiment, expresses joy to be reunited with his family again. Defense Dept. photo by Catherine D. Johnson  1Lt. Timothy Lewis with Company C, 2nd Battalion, 3rd Aviation Regiment, poses for picture with his wife and mother. Lt. Lewis is being redeployed to Fort Stewart, Ga. from Operation Iraqi Freedom.Defense Dept. photo by Catherine D. Johnson

|

Good job, Sam. Thanks so much.

|

Weapons Search

American soldier Sfc. Soden from the 4th Infantry division searches in the thick vegetation of a orchard during an early morning raid on a village outside Tikrit, Iraq, Wednesday, Sept. 24, 2003. The raid was conducted after intelligence was gathered with a cache of weapons being found buried in an orchard close to houses that were targeted for the operation.(AP Photo/Rob Griffith)  American soldier Spc Jeff Barnaby of Mansfield, La., from the 4th Infantry division, carries an automatic weapon found during an early morning raid on a village outside Tikrit, Iraq, Wednesday, Sept. 24, 2003.  An American soldier from the 4th Infantry division digs for hidden weapons during an early morning raid on a village outside Tikrit, Iraq, Wednesday, Sept. 24, 2003.  An American soldier from the 4th Infantry division battles with thick vegetation while searching for weapons during an early morning raid on a village outside Tikrit, Iraq, Wednesday, Sept. 24, 2003.  An American soldier from the 4th Infantry division stands guard over a suspected Saddam loyalist during an early morning raid on a village outside Tikrit, Iraq, Wednesday, Sept. 24, 2003.  A U.S. soldier runs past an armored vehicle 'Bradley' during a joint raid on a farmhouse by the 1st Battalion (22nd regiment) of the fourth Division of the U.S. army and the Iraqi Civil Defense Corps on the outskirts of Tikrit, about 110 miles (180 kilometers) northwest of Baghdad September 24, 2003. A machine gun and its ammunition were found during the raid. REUTERS/Arko Datta  A U.S. soldier searches a farm during a joint raid on a farmhouse by the 1st Battalion (22nd regiment) of the fourth Division of the U.S. army and the Iraqi Civil Defense Corps on the outskirts of Tikrit, about 110 miles (180 kilometers) northwest of Baghdad September 24, 2003.  U.S. soldiers walk through woods searching for arms and ammunition during a joint raid on a farmhouse on the outskirts of Tikrit, Iraq September 24, 2003.  A U.S. soldier digs out a hidden machine gun during a raid on a farmhouse near Tikrit, Iraq September 24, 2003. A machine gun and ammunition were found during the raid. Photo by Arko Datta/Reuters  American Soldiers from 4th Infantry division drive through an orchard during an early morning raid on a village outside Tikrit, Iraq (news - web sites), Wednesday, Sept. 24, 2003. With most of Iraq being desert, such green overgrown vegitation such as the orchard is few and far between.

|

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.