|

are acknowledged, affirmed and commemorated.

|

Posted on 01/23/2003 5:36:38 AM PST by SAMWolf

|

are acknowledged, affirmed and commemorated.

|

|

|

|

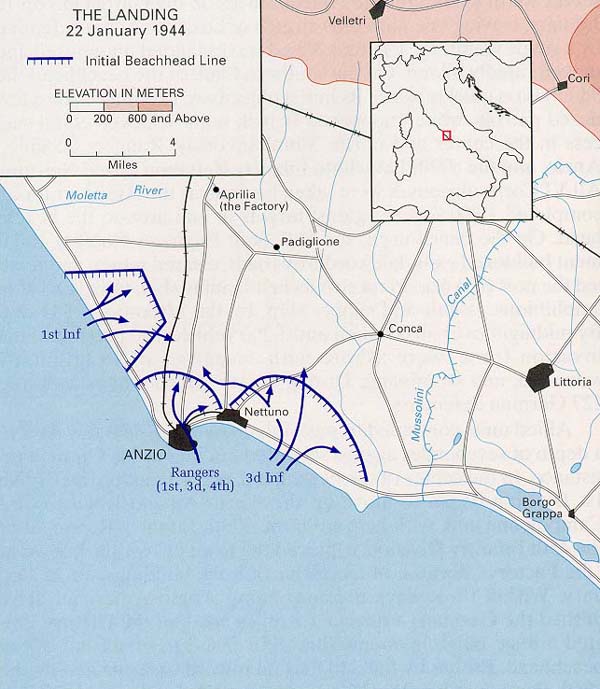

22 January-24 May 1944 During the early morning hours of 22 January 1944, troops of the Fifth Army swarmed ashore on a fifteen-mile stretch of Italian beach near the prewar resort towns of Anzio and Nettuno. The landings were carried out so flawlessly and German resistance was so light that British and American units gained their first day's objectives by noon, moving three to four miles inland by nightfall. The ease of the landing and the swift advance were noted by one paratrooper of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82d Airborne Division, who recalled that D-day at Anzio was sunny and warm, making it very hard to believe that a war was going on and that he was in the middle of it. The location of the Allied landings, thirty miles south of Rome and fifty-five miles northwest of the main line of resistance running from Minturno on the Tyrrhenian Sea to Ortona on the Adriatic, surprised local German commanders, who had been assured by their superiors that an amphibious assault would not take place during January or February. Thus when the landing occurred the Germans were unprepared to react offensively. Within a week, however, as Allied troops consolidated their positions and prepared to break out of the beachhead, the Germans gathered troops to eliminate what Adolf Hitler called the "Anzio abscess." The next four months would see some of the most savage fighting of World War II. Following the successful Allied landings at Calabria, Taranto, and Salerno in early September 1943 and the unconditional surrender of Italy that same month, German forces had quickly disarmed their former allies and begun a slow, fighting withdrawal to the north. Defending two hastily prepared, fortified belts stretching from coast to coast, the Germans significantly slowed the Allied advance before settling into the Gustav Line, a third, more formidable and sophisticated defensive belt of interlocking positions on the high ground along the peninsula's narrowest point. The Germans intended to fight for every portion of this line, set in the rugged Apennine Mountains overlooking scores of rain-soaked valleys, marshes, and rivers. The terrain favored the defense and, as elsewhere in Italy, was not conducive to armored warfare. Luftwaffe Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, whom Hitler had appointed as commander of all German forces in Italy on 6 November 1943, promised to hold the Gustav Line for at least six months. As long as the line was maintained it prevented the Fifth Army from advancing into the Liri valley, the most logical and direct route to the major Allied objective of Rome. The validity of Kesselring's strategy was demonstrated repeatedly between October 1943 and January 1944 as the Allies launched numerous costly attacks against well-entrenched enemy forces. The idea for an amphibious operation near Rome had originated in late October 1943 when it became obvious that the Germans were going to fight for the entire peninsula rather than withdraw to northern Italy. The Allied advance following the Salerno invasion was proving so arduous, due to poor weather, rough terrain, and stiffening resistance, that General Dwight D. Eisenhower pessimistically told the Anglo-American Combined Chiefs of Staff that there would be very hard and bitter fighting before the Allies could hope to reach Rome. As a result, Allied planners were looking for ways to break out of the costly struggle for each ridge and valley, which was consuming enormous numbers of men and scarce supplies. The Anzio invasion began at 0200 on 22 January 1944 and achieved, General Lucas recalled, one of the most complete surprises in history. The Germans had already sent their regional reserves south to counter the Allied attacks on the Garigliano on 18 January, leaving one nine-mile stretch of beach at Anzio defended by a single company. The first Allied waves landed unopposed and moved rapidly inland. On the southern flank of the beachhead the 3d Division quickly seized its initial objectives, brushing aside a few dazed patrols, while unopposed British units achieved equal success in the center and north. Simultaneously, Rangers occupied Anzio, and the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion seized Nettuno. All VI Corps objectives were taken by noon as the Allied air forces completed 1,200 sorties against targets in and around the beachhead. On the beach itself, the U.S. 36th Engineer Combat Regiment bulldozed exits, laid corduroy roads, cleared mines, and readied the port of Anzio to receive its first landing ship, tank (LST), an amphibious assault and supply ship, by the afternoon of D-day. By midnight over 36,000 men and 3,200 vehicles, 90 percent of the invasion force, were ashore with casualties of 13 killed, 97 wounded, and 44 missing. During D-day Allied troops captured 227 German defenders.  Allied units continued to push inland over the next few days to a depth of seven miles against scattered but increasing German resistance. In the center of the beachhead, on 24 January, the British 1st Division began to move up the Anzio-Albano Road toward Campoleone and, with help from the 179th Infantry Regiment of the 45th Infantry Division, captured the town of Aprilia, known as "the Factory" because of its cluster of brick buildings, on 25 January. Within three days the continuing Anglo-American drive pushed the Germans a further 1.5 miles north of the Factory, created a huge bulge in enemy lines, but failed to break out of the beachhead. Probes by the 3d Division toward Cisterna and by the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment toward Littoria on 24-25 January made some progress but were also halted short of their goals by stubborn resistance. Renewed attacks on the next day brought the Americans within three miles of Cisterna and two miles beyond the west branch of the Mussolini Canal. But the 3d Division commander, Maj. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott, Jr., on orders of the corps commander, called a halt to the offensive, a pause that later lengthened into a general consolidation and reorganization of beachhead forces between 26 and 29 January. Meanwhile, the Allied troop and materiel buildup had proceeded at a breakneck pace. Despite continuous German artillery and air harassment, a constant fact of life throughout the campaign, the Allies off-loaded twenty-one cargo ships and landed 6,350 tons of materiel on 29 January alone, and on 1 February the port of Anzio went into full operation. Improving air defenses downed ninety-seven attacking Luftwaffe aircraft prior to 1 February, but the Germans did succeed in sinking one destroyer and a hospital ship, as well as destroying significant stocks of supplies piled on the crowded beaches. Mindful of the need for reinforcements, Lucas ordered ashore the rest of the 45th Infantry Division and remaining portions of the 1st Armored Division allotted to the Anzio operation, raising the total number of Allied soldiers in the beachhead to 61,332.  The Germans had not been idle during the week after the Anzio landing. The German Armed Forces High Command (OKW) in Berlin was surprised at the location of the landing and the efficiency with which it was carried out. Although they had considered such an attack probable for some time and had made preliminary plans for meeting it, Kesselring and his local commanders were powerless to repel the invasion immediately because of the lack of adequate reserves. Nevertheless, German reaction to the Anzio landing was swift and ultimately would prove far more powerful than anything the Allies had anticipated. Upon receiving word of the landings, Kesselring immediately dispatched elements of the 4th Parachute and Hermann Goering Divisions south from the Rome area to defend the roads leading north from the Alban Hills. Within the next twenty-four hours Hitler dispatched other units to Italy from Yugoslavia, France, and Germany to reinforce elements of the 3d Panzer Grenadier and 71st Infantry Divisions that were already moving into the Anzio area. By the end of D-day, thousands of German troops were converging on Anzio, despite delays caused by Allied air attacks. OKW, Kesselring, and Brig. Gen. Siegfried Westphal, Kesselring's chief of staff, were astonished that the Anzio forces had not exploited their unopposed landing with an immediate thrust into the virtually undefended Alban Hills on 23-24 January. As Westphal later recounted, there were no significant German units between Anzio and Rome, and he speculated that an imaginative, bold strike by enterprising forces could easily have penetrated into the interior or sped straight up Highways 6 and 7 to Rome. Instead, Westphal recalled, the enemy forces lost time and hesitated. As the Germans later discovered, General Lucas was neither bold nor imaginative, and he erred repeatedly on the side of caution, to the increasing chagrin of both Alexander and Clark.  By 24 January Kesselring, confident that he had gathered sufficient forces to contain the beachhead, transferred the Fourteenth Army headquarters under General Eberhard von Mackensen from Verona in northern Italy to Anzio. Mackensen soon controlled elements of 8 divisions, totaling 40,000 troops, with 5 more divisions on the way. Seeking to prevent a permanent Allied foothold at Anzio, Kesselring ordered a counterattack for 28 January, but Mackensen requested and received a postponement until 1 February to await further reinforcements, especially armored units that were being held up by Allied air attacks. Two days before the scheduled offensive, the Fourteenth Army numbered about 70,000 combat troops, most already deployed in forward staging areas, with several thousand more on the way. Racing against the expected German counterattack, both the Fifth and Eighth Armies prepared to renew their stalled offensives in the south. Lucas meanwhile planned a two-pronged attack for 30 January. While one force cut Highway 7 at Cisterna before moving east into the Alban Hills, a second was to advance northeast up the Albano Road, break through the Campoleone salient, and exploit the gap by moving to the west and southwest. A quick link-up with Fifth Army forces in the south was believed still possible even though German resistance all along the perimeter of the beachhead was becoming stronger.

|

Monte Cassino, Italy 1944

Monte Cassino Cross

(Krzyz Monte Cassino)

This is very sad news indeed.

Beer Barrel Polka (Another version: Texas Flavor)

J

Caliber: 11.02 inches (280 mm) Barrel Length: 70.08 feet Overall Length: 135.28 feet Weight in Action: 214.59 tons Elevation: 0° to 50° Traverse: 2° Shell and Weight: HE; 563.38 lbs Muizzle Velocity: 3,700 fps Maximum Range: 38.64 milesThis was one of the best workaday railway guns ever built. The K5(E) formed the background of the German railway artillery force during World War II and saw wide use. Two examples of the K5(E) survived World War II. One K5(E) is on display at Cap Griz Nez in France, the other "Anzio Annie" (above) is on display at the Aberdeen Proving Grounds Museum, Aberdeen Maryland. This particular gun is the one that was used in the shelling of the US troops during their landing at Anzio, Italy.

The deployment of radio guided missiles was well practiced. A bomber would circle enemy ships and activate the missile's guidance system. The commander, pilot or bombardier singled out a target from a high altitude. The port side missile was released first. As the missile was in free fall, the missile's speed and radio guidance were rechecked. The bombardier would attempt to guide the missile onto its target, while the pilot maintained a parallel course to the target. Once the first missile hit or passed the target, the bomber circled again and launched the starboard missile in the same manner. The time spent circling in the air by the Luftwaffe bombers might exceed an hour. This depended on the type of Allied fighter flown in to engage these high altitude bombers.

Luftwaffe bombers equipped with the Henschel Hs 293 guided missiles had to make their runs close to 4,500 feet, which put them at risk of being hit from Allied anti-aircraft shelling or fighter aircraft. The Luftwaffe scored more hits with the Hs 293's close to dusk. The deployment of the Fritz-X could be done at anytime during daylight hours. These specially equipped bombers flew between 18,000 and 20,000 feet and were rarely shot down by Allied forces. When the P-38 Lighting entered service in Europe, the Luftwaffe ended its use of radio guided missiles against Allied ships.

At the commencement of Operation Shingle (Invasion of Anzio), the Allied forces anticipated the deployment of radio guided missiles. As a countermeasure, Naval Command placed US Army fighter-direction teams aboard ships, USS Frederick C. Davis and USS Herbert C. Jones. Their job was to monitor all Luftwaffe radio frequencies and intercept and jam any radio signals sent from a bomber to a guided missile with the anticipation of forcing a miss produced by a lost signal. This strategy started a new trend in aerial aviation.

OPERATION SHINGLE (Invasion of Anzio, Italy - 22 Jan. 1944)

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.