|

Posted on 08/11/2004 10:39:29 PM PDT by SAMWolf

|

|

are acknowledged, affirmed and commemorated.

|

| Our Mission: The FReeper Foxhole is dedicated to Veterans of our Nation's military forces and to others who are affected in their relationships with Veterans. In the FReeper Foxhole, Veterans or their family members should feel free to address their specific circumstances or whatever issues concern them in an atmosphere of peace, understanding, brotherhood and support. The FReeper Foxhole hopes to share with it's readers an open forum where we can learn about and discuss military history, military news and other topics of concern or interest to our readers be they Veteran's, Current Duty or anyone interested in what we have to offer. If the Foxhole makes someone appreciate, even a little, what others have sacrificed for us, then it has accomplished one of it's missions. We hope the Foxhole in some small way helps us to remember and honor those who came before us.

|

|

The Mexican War between the United States and Mexico began with a Mexican attack on American troops along the southern border of Texas on Apr. 25, 1846. Fighting ended when U.S. Gen. Winfield Scott occupied Mexico City on Sept. 14, 1847; a few months later a peace treaty was signed (Feb. 2, 1848) at Guadalupe Hidalgo. In addition to recognizing the U.S. annexation of Texas defeated Mexico ceded California and , New Mexico (including all the present-day states of the Southwest) to the United States.  As with all major events, historical interpretations concerning the causes of the Mexican War vary. Simply stated, a dictatorial Centralist government in Mexico began the war because of the U.S. annexation (1845) of Texas, which Mexico continued to claim despite the establishment of the independent republic of Texas 10 years before. Some historians have argued, however, that the United States provoked the war by annexing Texas and, more deliberately, by stationing an army at the mouth of the Rio Grande. Another, related, interpretation maintains that the administration of U.S. President James K. Polk forced Mexico to war in order to seize California and the Southwest. A minority believes the war arose simply out of Mexico's failure to pay claims for losses sustained by U.S. citizens during the Mexican War of Independence. At the time of the war, Mexico had a highly unstable government. The federal constitution of 1824 had been abrogated in 1835 and replaced by a centralized dictatorship. Two diametrically opposed factions had arisen: the Federalists, who supported a constitutional democracy; and the Centralists, who supported an autocratic government under a monarch or dictator. Various clashing parties of Centralists were in control of the government from 1835 to December 1844. During that time numerous rebellions and insurgencies occurred within Mexican territory, including the temporary disaffection of California and the Texas Revolution, which resulted in the independence (1836) of Texas.  Jose Joaquin Herrera In December 1844 a coalition of moderates and Federalists forced the dictator Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna into exile and installed Jose Joaquin Herrera as acting president of Mexico. The victory was a short-lived, uneasy one. Although Santa Anna himself was in Cuba, other Centralists began planning the overthrow of Herrera, and the U.S. annexation of Texas in 1845 provided them with a jingoistic cause.  James K. Polk The U.S. annexation of Texas, by a joint congressional resolution (Feb. 27-28, 1845), had caused considerable political debate in the United States. The desire of the Texas Republic to join the United States had been blocked for several years by antislavery forces, who feared that several new slave states would be created from the Texas territory. The principal factor that led the administration of John Tyler to take action was British interest in independent Texas. Indeed, anti-British feeling lay behind most of the expansionist policy statements of the United States in this period. James Polk won the 1844 presidential election by advocating a belligerent stand against Britain on the Oregon Question. Once in office he declared that "the people of this continent alone have the right to decide their own destiny." About the same time the term Manifest Destiny came into vogue to describe what was regarded as a God-given right to expand U.S. territory. The term was applied particularly to the Oregon dispute, but it had relevance also to California, where American settlers warned of British intrigues to take control, and to Texas. As early as August 1843, Santa Anna's government had informed the United States that it would "consider equivalent to a declaration of war . . . the passage of an act for the incorporation of Texas." The government of Herrera did not take this militant position. It had already initiated steps, encouraged by the British, to recognize the independence of the Republic of Texas, and although Santa Anna's lame-duck minister in Washington broke diplomatic relations with the U.S. government immediately after annexation, in August 1845 the Herrera government indicated willingness to resume relations. Not only was the Herrera government prepared to accept the loss of Texas, but it also hoped to lay to rest the claims question that had plagued U.S.-Mexican affairs since 1825. Britain and France had used force, or the threat of it, to induce the Mexican government to pay their claims on behalf of their citizens. The United States, however, preferred to negotiate, and the negotiations had dragged on interminably.  Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna Fearing that American patience was running short, Herrera seemed determined to settle the issue. He requested that the United States send a minister plenipotentiary to Mexico, and President Polk appointed John Slidell. Slidell's authority, however, may have exceeded Herrera's intentions. Slidell was authorized to purchase California and New Mexico from Mexico and to settle the Texas boundary, which was a source of dispute even with the Mexican moderates. While the Republic of Texas had claimed the Rio Grande as its boundary, the adjacent Mexican state of Tamaulipas claimed the area north of the Rio Grande to the Nueces River.  John Slidell By the time Slidell arrived in Mexico in December 1845, the Herrera government was under intense fire from the Centralists for its moderate foreign policies. The Centralist strategy was to appeal to Mexican national pride as a means of ousting Herrera. During August 1845 their leader, Mariano Parades y Arrillaga, began to demand an attack on the United States. When Slidell arrived, Herrera, in an effort to save his government, refused to meet with him. A few days later (December 14), Parades issued a revolutionary manifesto; he entered Mexico City at the head of an army on Jan. 2, 1846. Herrera fled, and Parades, who assumed the presidency on January 4, ordered Slidell out of Mexico.  Cavalry soldier and Infantry Lieutenant, US Army Regulars, 1847. Courtesy of the US Army Center for Military History After the failure of the Slidell mission, Polk ordered Zachary Taylor to move his army to the mouth of the Rio Grande and to prepare to defend Texas from invasion. Taylor did so, arriving at the Rio Grande on Mar. 28, 1846. Abolitionists in the United States, who had opposed the annexation of Texas as a slave state, claimed that the move to the Rio Grande was a hostile and aggressive act by Polk to provoke a war with Mexico to add new slave territory to the United States.  Mariano Parades y Arrillaga Whatever Polk's precise intentions were, for the Centralists in Mexico the annexation of Texas had been sufficient cause for war; they saw no disputed boundary--Mexico owned all of Texas. Before Taylor had moved to the Rio Grande, Parades had begun mobilizing troops and had reiterated his intention of attacking. On April 4 the new dictator of Mexico ordered the attack on Taylor. When his commander at Matamoros delayed, Parades replaced him, issued a declaration of war (April 23), and reordered the attack.

|

Mexican leaders clearly expected to win these battles as well as to recover Texas and win the war. Parades spoke grandly of occupying New Orleans and Mobile. His army of about 32,000 men was four to six times the size of the original U.S. army. Furthermore, Mexican troops were well armed, disciplined, and, above all, experienced in scores of revolutions. Parades also counted on logistics. The principal theater of war would be Texas, hundreds of miles from the populous areas of the United States. Many Centralists believed that abolitionists' objections to the war would demoralize the United States, and some Centralists believed a Mexican invasion would be supported by a massive slave uprising.

Taylor occupied Matamoros on May 18 but then delayed for several months before moving south. He was apparently waiting for transportation promised him by the U.S. government, though his critics branded him inept. In July he moved his base up the Rio Grande to Camargo, but it was only in August that Taylor began planning the attack on Monterrey.

The Mexicans did not attack because the Centralist government was collapsing. Rather than uniting Mexico, the war had given the Federalist faction an opportunity to rebel. Even while Taylor had been camped on the Nueces in the fall of 1845, a few Federalist leaders had been in contact with him, promising supplies and asking for assistance in overthrowing Parades. Northern Mexico was almost a Federalist stronghold, and as Taylor moved to the Rio Grande, he received increasing support from the rebels.

In the meantime, Taylor began his advance on Monterrey. He reached that fortified town, which had a garrison of more than 10,000 troops, on September 19 and began his attack on the morning of September 21. With about 2,000 men, Gen. William J. Worth captured the road between Monterrey and Saltillo and by noon was storming Federation Hill. Six companies of Texas Rangers charged up the hill, seized the enemy artillery, and turned the cannon on retreating Mexican forces. On the opposite side of the city a diversionary attack penetrated the town, despite much confusion. On September 22 the Americans rested, but they resumed the attack the next day. After bloody street-to-street fighting, the Mexican general Pedro de Ampudia requested and was granted a truce. On September 25 he was permitted to withdraw his forces from the city, and an 8-week armistice was agreed upon. Total Mexican casualties were estimated at 367. The Americans had 368 wounded and 120 killed.

www.utep.edu

www.grunts.net

www.dmwv.org

www.npg.si.edu

www.arts-history

www.humanities-interactive.org

www.militarymuseum.org rip.physics.unk.edu

www.army.mil

www.diggerhistory.info

www.oldgloryprints.com

www.npg.si.edu

www.gagos.com

www.radicalmoderates.org

Despite the objections of the abolitionists, the war received enthusiastic support in all sections of the United States and was fought almost entirely by volunteers. The army swelled from just over 6,000 to over 115,000. Of this total approximately 1.5 percent were killed in the fighting, and nearly 10 percent died of disease; another 12 percent were wounded or discharged because of disease or both. For years afterward, Mexican War veterans continued to suffer from the debilitating diseases contracted during the campaigns. The casualty rate was thus easily over 25 percent for the 17 months of the war; the total casualties may have reached 35-40 percent if later injury- and disease-related deaths are added. In this respect the war was the most disastrous in American military history.  News from the Mexican War (Richard Woodville) During the war political quarrels arose regarding the disposition of conquered Mexico. A strong "All-Mexico" movement urged annexation of the entire territory. Abolitionists opposed that position and fought for the exclusion of slavery from any territory absorbed by the United States. In 1847 the House of Representatives passed the Wilmot Proviso, stipulating that none of the territory acquired should be open to slavery. The Senate avoided the issue, and a late attempt to add it to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was defeated.  Mexico City The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was the unsatisfactory result of Nicholas Trist's unauthorized negotiations. It was reluctantly approved by the U.S. Senate on Mar. 10, 1848, and ratified by the Mexican Congress on May 25. Mexico's cession of California and New Mexico and its recognition of U.S. sovereignty over all Texas north of the Rio Grande formalized the addition of 3.1 million sq km (1.2 million sq mi) of territory to the United States. In return the United States agreed to pay $15 million and assumed the claims of its citizens against Mexico. A final territorial adjustment between Mexico and the United States was made by the Gadsden Purchase in 1853.  The War with Mexico is notable for a number of "firsts."

|

Join us at the rally we call:

What: A peaceful remembrance of those with whom we served in Vietnam - those who lived and those who died.

We will tell the story of their virtues and how that contrasts with the lies told by John Kerry.

When: Sunday, Sept. 12, 2004 @ 2:00 PM - 4:00 PM EDT

Where: The West Front of the U.S. Capitol Building, Washington, DC

All Vietnam veterans and their families and supporters are asked to attend. Other veterans are invited as honored guests. This will be a peaceful event--no shouting or contact with others with different opinions. We fought for their rights then, and we respect their rights now. This is NOT a Republican or a pro-Bush rally. Democrats, Republicans and independents alike are warmly invited.

Our gathering is to remember those with whom we served, thereby giving the lie to John Kerry's smear against a generation of fine young men. B.G. "Jug" Burkett, author of "Stolen Valor," will be one of our speakers. Jug has debunked countless impostors who falsely claimed to be Vietnam veterans or who falsely claimed awards for heroism. Jug recommends that we refrain from dragging fatigues out of mothballs. Dress like America, like you do every day.

Dress code: business casual, nice slacks, and shirt and shoes. No uniform remnants, please. Unit hats OK.

Selected members will wear badges identifying them as authorized to speak to the media about our event. Others who speak to the media will speak only for themselves.

The program will be controlled in an attempt to stay on-message. Speakers are encouraged not to engage in speculative criticism of John Kerry but (1) to stick to known and undisputed facts about John Kerry’s lies while (2) reminding America of the true honor and courage of our brothers in battle in Vietnam.

Send this announcement to 10 or more of your brothers! Bring them by car, bus, train or plane! Make this event one of pride in America, an event you would be proud to have your mother or your children attend.

Contact: kerrylied.com

I'm going to call it an early night and turn in. Good night Sam.

Good Night Snippy.

American ingenuity. Gotta love it.

Death of Major Ringgold at Palo Alto

The "modern," and most lustrous history of the 2nd Artillery, began with Secretary of War Joel Poinsett’s order to establish a camp of instruction for the light artillery at Camp Washington, near Trenton, New Jersey. For the 2nd it was Company A with Lt. James Duncan (USMA class of 1834) in command. The others were K of the 1st under Capt. Francis Taylor, C of the 3rd under Major Samuel Ringgold, and B of the 4th under Capt. John Washington--one additional company, E of the 3rd under Capt. Braxton Bragg, was added prior to the Mexican-American War.

All of the newly designated light artillery companies were ordered to a camp of instruction, Camp Washington, in 1839, for three months of training. Afterwards, Company A served at Buffalo and Ft. Hamilton, New York. The impending hostilities with Mexico found Company A, along with other units of the infantry and artillery, in route to Corpus Christi, Texas, to Join "Old Rough and Ready," General Zachary Taylor, arriving sometime during September or October of 1845. There, Duncan and his men joined General William Worth's division (of Ft. Worth, Texas, fame)

Moving southward with Taylor into the disputed area between the Nueces and Rio Grande rivers, Duncan figured prominently in the first two battles of the war. At Palo Alto (place of the tall timber) on May 8, 1846, Duncan massed battery fire and then used obscuring smoke to change positions at a critical juncture of the battle, thereby surprising and greatly assisting in the defeat of the Mexican forces. As Taylor's army moved south the next day the enemy forces gave battle again at Resaca de la Palma (dry wash of the palms).

Determined not to repeat the mistakes of the previous day, i.e., affording the American artillery clear vistas of fire and ample room to maneuver, the Mexican commander, General Arista, picked a spot which would make it difficult for the gunners to use their weapons as they had the day before. In so doing, the Mexican commander also made it difficult for his own troops, especially the much feared lancers, to demonstrate to their best advantage. While the American artillery did not play as significant a role at the Resaca as they did at Palo Alto, it is fair to suggest that their mere presence still greatly influenced the conduct and outcome of the battle.

As was the case the day before, the Mexicans retired from the field at Resaca de la Palma leaving it in American hands and effectively conceding victory to General Taylor’s army. This time, however, the Mexican Army did not stop until they reached the safety of Matamoros, below the Rio Grande. Duncan won two brevets in the opening days of the war, one for each of the battles. Palo Alto also saw the demise of the most famous artilleryman in the Army. Major Samuel Ringgold was wounded through both legs and died a few days later. It was he who formed and drilled the first "flying batteries." Ringgold is remembered by artillerymen as the first operational innovator of what today would be called "shoot and scoot" tactics, having no doubt borrowed from predecessors Gribeauval and Lieutenant George Peter. His command was assumed by Capt. Randolph Ridgely, himself to succumb to a fall from his horse after the Battle of Monterrey.

Samuel Ringgold

(1796-1846)

Mexican War Officer

A member of the first graduating class of the United States Military Academy at West Point (1818), Ringgold, an artillery officer, was on General Winfield Scott's staff when this portrait was painted. In 1846, in the first clash of the Mexican War, Ringgold led a small American force to victory at Palo Alto. Wounded, he died three days later. News of his death, the first of the war, created an explosion of national pride, and he became a hero.

"Death of Major Ringgold, of the Flying Artillery, at the Battle of Palo Alto, (Texas) May 8th, 1846."

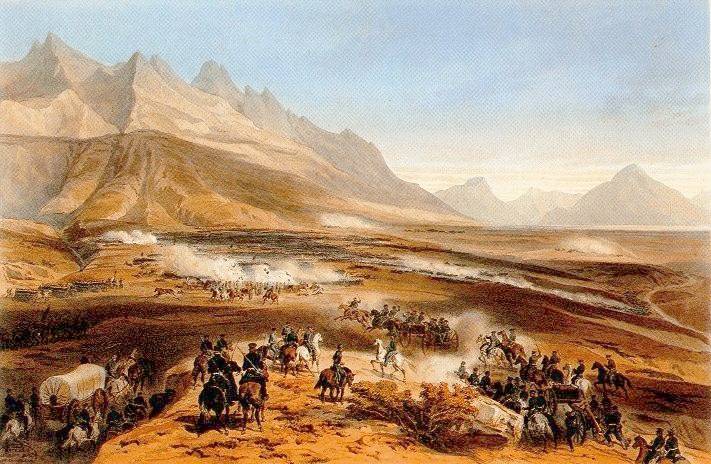

View of the moment witnessed by Capt. James H. Carleton "when O'Brien was so gallantly striving to hold the Mexicans in check during their last attack upon the great plateau." It occurred while the Kentucky and Illinois infantry were meeting with disaster in the ravine (depicted by the thin strip of smoke, middle right). A large mass of attacking Mexican infantry (center, in distance) threatens Gen. Taylor and his staff (foreground). Nothing stands between them but a battery of three guns under Capt. John P. O'Brien (center). Another gun, commanded by Capt. Braxton Bragg, has just arrived in the right foreground. At far left is Col. Jefferson Davis' 1st Mississippi Infantry and Gen. Joseph Lane with the 3rd Indiana and remnants of the 2nd Indiana rushing to the weak point.

O'Brien saw that if he stood his ground and fought until his guns were captured there was a chance remaining to retrieve the fortunes of the day. By the time he was captured, nearly all of his battery had been killed or wounded. But, they hung on long enough: Bragg, Davis and Lane and their troops arrived to repel the last Mexican assault. During the night the Mexican army retreated down the valley to the south. Taylor reported 272 killed and 387 wounded. The Mexican losses were estimated at double that number. The battle left the Americans in control of Northern Mexico.

TO THE HON. SECRETARY OF WAR:

Sir: - I have the honor to submit a detailed report of the operations of the forces under my command, which resulted in the engagement of Buena Vista, the repulse of the Mexican army, and the reoccupation of this position.

About eight o'clock, a strong demonstration was made against the centre of our position, a heavy column moving along the road. This forces was soon dispersed by a few rapid and well-directed shots from Captain Washington's battery.

In order to bring his men within effective range, General Lane ordered the artillery and Second Indiana regiment forward. The artillery advanced within musket-range of it with great effect, but without being able to check its advance. The infantry ordered to its support had fallen back in disorder, being exposed, as well as the battery, not only to a severe fire of small-arms from the front, but also to a murderous cross-fire of grape and canister, from a Mexican battery on the left. Captain O'Brien found it impossible to retain his position without support, but was only able to withdraw two of his pieces, all the horses and cannoneers of the third piece being killed or disabled.

The batteries of Captains Sherman and Bragg were in position on the plateau, and did much execution, not only in front, but particularly upon the masses which had gained our rear.

The moment was most critical. Captain O'Brien, with two pieces, had sustained this heavy charge to the last and was finally obliged to leave his guns on the field - his infantry support being entirely routed. Captain Bragg, who had just arrived from the left, was ordered at once into battery. Without any infantry to support him, and at the imminent risk of losing his guns, this officer came rapidly into action, the Mexican line being but a few yards from the muzzle of his pieces. The first discharge of canister caused the enemy to hesitate; the second and third drove him back in disorder and saved the day. The Second Kentucky regiment, which had advanced beyond supporting distance in this affair, was driven back and closely pressed by the enemy's cavalry. Taking a ravine which led in the direction of Captain Washington's battery, their pursuers became exposed to his fire, which soon checked and drove them back with loss. In the mean time the rest of our artillery had taken position on the plateau, covered by the Mississippi and Third Indiana regiments, the former of which had reached the ground in time to pour a fire into the right flank of the enemy, and thus contribute to his repulse.

The services of the light artillery, always conspicuous, were more than usually distinguished. Moving rapidly over the roughest ground, it was always in action at the right place and the right time, and its well-directed fire dealt destruction in the masses of the enemy. While I recommend to particular favor the gallant conduct and valuable services of Major Munroe, chief of artillery, and Captains Washington, Fourth artillery, and Sherman and Bragg, Third artillery, commanding batteries, I deem it no more than just to mention all the subaltern officers. They were nearly all detached at different times, and in every situation exhibited conspicuous skill and gallantry. Captain O'Brien, Lieutenants Brent, Whiting, and Couch, Fourth artillery, and Bryan, topographical engineers, (slightly wounded,) were attached to Captain Washington's battery. Lieutenants Thomas, Reynolds, and French, Third artillery, (severely wounded,) to that of Captain Sherman; and Captain Shover and Lieutenant Donaldson, First artillery, rendered gallant and important service in repulsing the cavalry of General Minon.

A Little More Grape, Capt Bragg

Good morning, snippy and everyone at the Freeper Foxhole.

Thanks for the adders No. 4

Looks like lots of good reading this afternoon

Off to a short work day Foxhole Bump

Regards

alfa6 ;>}

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.