The Chastisement of John Malcolm

In 1774, John Malcolm was a Crown customs collector, based in Boston. At that time Boston had had five years of civic tension culminating in the Boston Massacre. Malcolm, like most Crown representatives didn't much like the Bostonians and harboured smouldering resentment against the uppity locals who had been resisting Crown authority since the Stamp Act in 1768. They made his job difficult. Malcolm had more reason than most to hold a grudge against the colonists. He had only recently had a run-in with the good people of Portland, Maine on a customs matter over which they had disagreed. The Portland folks saw fit to tar and feather Malcolm but were kind enough to allow him to remain clothed for the treatment. A prideful man who was impressed by his own authority this didn't sit well.

In the snow covered streets of Boston in January Malcolm was run over by a boy sledding in the street. Malcolm, his temper getting the best of him, raised his cane to strike the boy. George Hewes, a local shoemaker, intervened and Malcolm turned on Hewes. At first, Malcolm tried to overawe Hewes with his social rank - being a gentleman and, in Malcolm's mind, a hero of the French and Indian War. Hewes took the vituperation of Malcolm with a grain of salt and retorted "Be that as it may, I was never tarred and feathered." That was the match to Malcolm's tinder and he flew at Hewes and struck him a near fatal blow to the head with his cane.

The town of Boston was electric with tension between the locals and Crown representatives and word of this attack spread almost instantly. A crowd gathered at Malcolm's house while he shouted out a window, relishing baiting the crowd into an uproar, and flourishing with his sword, eventually stabbing one man in the chest.

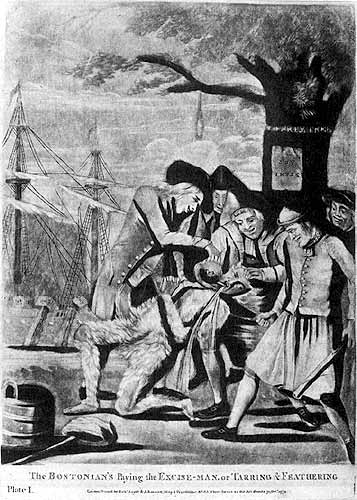

The crowd swarmed the house, forcing Malcolm to retreat to the second floor. Malcolm was eventually disarmed and the crowd seized him, tied him, put him on a sled and dragged him through the town as brickbats rained upon him. After pulling him by the wharfs to pick up a barrel of tar, the mob took him to King St, by the Town House, where political rallies were customarily held and where the Massacre had occurred.

After pulling him by the wharfs to pick up a barrel of tar, the mob took him to King St, by the Town House, where political rallies were customarily held and where the Massacre had occurred.

In the chill of the coldest night of a Boston January Malcolm was stripped, dislocating his arm, and hot tar daubed on his bare skin, burning his flesh.

Feathers then were applied to give what was then called the "modern jacket". Malcolm was then paraded, both burned and freezing, from one end of the town to the other and back. At the Liberty Tree they threw a noose around his neck and threatened to hang him if he didn't denounce the Governor and the Customs Commissioners. He refused but they didn't hang him. Instead they paraded him back to the far end of town again, eventually rolling him out of the cart at his home "like a log."

Malcolm wasn't the first or last to suffer from the people's anger. In the time before Concord and Lexington many Crown representatives as well as colonists in government positions suffered their houses to be ransacked, demolished or fired and their persons to be insulted most cruelly. Soon, the British Regulars - the Redcoats - the Crown's SWAT teams of the time - which had been withdrawn after the Boston Massacre in an attempt to calm matters were returned in force and Boston was placed under martial law.