Posted on 12/18/2010 9:33:26 AM PST by neverdem

A strain of nitrogen-fixing ocean microbe has been found to be the most efficient hydrogen-producing microbe to date, boosting the prospect of one day using hydrogen as an environmentally friendly fuel.

The US team behind the discovery says the naturally occurring cyanobacteria Cyanothece 51142 turns solar energy into hydrogen under aerobic conditions at rates several times higher than any other known photosynthetic microbe.

Normally, microbes that produce hydrogen do so under anaerobic conditions. This is because the enzymes they use for hydrogen production, namely nitrogenase and/or hydrogenase, are inhibited by oxygen. By understanding the way Cyanothece 51142 grows and fixes nitrogen, the team learned that nitrogenase was involved in its metabolism, raising suspicions of its hydrogen producing potential under unusually aerobic conditions.

'We expected high rates of hydrogen production, but we were very surprised to find such high rates "right out of the box,"' says co-author Louis Sherman, of Purdue University in West Layafette, Indiana, who collaborated with Himadri Pakrasi's lab at Washington University in Missouri, US. 'The strain has amazing capabilities and we think that there is still untapped potential.'

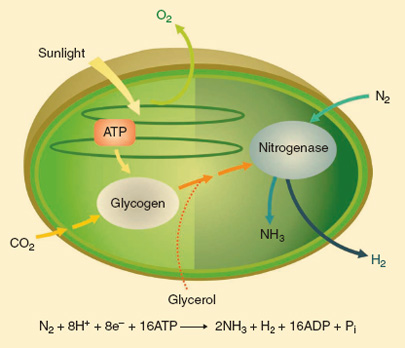

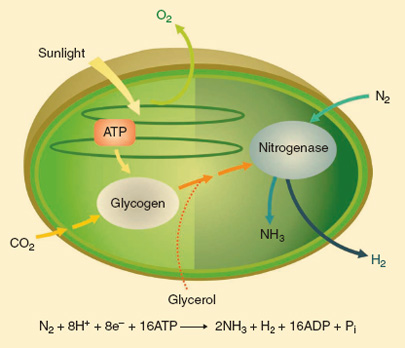

Cyanothece 51142 is able to produce hydrogen aerobically because it controls its metabolic processes by a circadian clock. It photosynthesises during the day and fixes carbon which it stores as glycogen, and at night it begins fixing nitrogen using the glycogen as an energy source and nitrogenase to convert N2 to NH3 with H2 as a byproduct. Although oxygen is present, high rates of respiration create an anaerobic environment in the cells which allows nitrogenase to function.

|

Biohydrogen production by Cyanothece 51142 cells using solar energy and atmospheric CO2 and/or glycerol. CO2 is fixed during the day to synthesise glycogen, which serves as an energy reserve and electron source for H2 production at night

© Nature Commun

|

The team experimented with various conditions to optimise the cyanobacteria's hydrogen production, and found that the microbes produced much more hydrogen if grown in the presence of additional carbon sources including glycerol, a waste product of industrial biodiesel production. The extra carbon is thought to boost the activity of nitrogenase.

By growing cells in glycerol-supplemented media and incubating under an argon atmosphere, the team obtained its highest yield of 467umol of hydrogen per mg of chlorophyll per hour, an order of magnitude higher than any other known hydrogen producing photosynthesising microbe.

'The nitrogenase system in general has been dismissed by many scientists as a sustainable route to photo-H2, in large part owing to the additional overhead paid for cellular energy in the form of ATP required by this pathway. The present work urges us to take a fresh look at this system,' says Charles Dismukes, who studies chemical methods for renewable solar-based fuel production at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, US. 'It is a superb example of what can be learned from mother nature and applied to biotechnological applications, though there is much to be studied before such a system could be utilised in the commercial sector,' he adds.

Sherman is aware of the challenges ahead but is hopeful that the work will boost research into hydrogen fuels. 'It will stimulate other biologists to keep studying photosynthetic microbes to find one with even better properties. And it will help policy makers realise that bio-hydrogen production is a possibility and enhance research into all of the other areas that need to be studied before a "hydrogen economy" is a reality,' he says.

A Bandyopadhyay et al, Nature Commun., 2010, DOI: 10.1038/ncomms1139

I prefer a fuel that is a liquid from -40 to 150 F.

Looking at their equation and the cell gozintas and goesoutas leaves the question of when in the H does the H come from?

But burning hydrogen produces Dihydrogen monoxide which is a known greenhouse gas, a component of acid rain, and can be fatal when inhaled. Try again.

Haven’t read the article, and the schematic supplied in the excerpt isn’t completely clear, but the bacterium can’t create hydrogen from nothing - there has to be some source of hydrogen atoms.

The equation suggests hydrogen in the form of protons; the schematic implies the hydrogen comes from glycerol. If the latter is correct, then for this process to have any economic value, one needs an efficient source of glycerol (that is, a process that makes glycerol cheaper than the value of the dihydrogen gas produced). I expect that can be done by some biological process; I don’t know if that’s the case now.

But even (especially) in biochemistry, you can’t get something from nothing - the Holy Grail would be a process that takes water to dihydrogen and dioxygen, powered by sunlight - this article appears to be at least a step in that direction.

micro ping

If they can find a practical way of collecting the hydrogen, this could be more than something of just an academic interest.

457 micromoles/mg chlorophyll of H2 per hour works out to 934 micrograms/milligram chlorophyll. 1000 micrograms = 1 milligram, for those who missed real science class (science class today is all about global warming and how humanity is a virus infecting the Earth Mother Goddess Gaia).

Now, is enough waste glycerol produced for the H2 to be returned to the refining process? As in crack the diesel fuel to make gasoline?

Hydrogen is hydrogen, calling it “biohytrogen” just reeks of crap-science.

It's loaded with availabe carbohydrates in the form of glycerol and glycogen, but it's more interesting to learn about the nitrogenase and hydrogenase enzymes involved, the genes that code for them and their potential for synthetic biology like recombinant DNA.

How else do you expect them to attract any grant money these days? Chemistry World comes from the Royal Society of Chemistry. If you think alternaive energy and climate change is a fad in the USA, they are obsessed with it in Great Britain. I just like the potential for cheap energy.

“But even (especially) in biochemistry, you can’t get something from nothing - . . .”

Well, except in wind and solar power. And in fossil fuel free electric cars. It is well known you can get something for nothing there. That’s why the government has chosen to fund these technologies extravagently.

to replace all hot air balloons,

including Al Gore

CC

Bingo. You win the boob prize. On every hydrogen thread there is always someone who mouths off about the Hindenberg.

The Hindenberg's problem wasn't caused by hydrogen, it was started by a lightening strike on the aluminized fabric of the zeppilin's "skin", which was essentially solid rocket fuel. It takes a high temperature to get started, but once set, it burns like fury. If you've seen the videos of the burning Hindenberg, you will notice clouds of dense black smoke. Hint, hydrogen burning in air doesn't produce smoke. But organics do, specifically the dope used to bind the aluminum to the fabric, and the diesel fuel for the engines. Of course, once the bags were breached, they hydrogen "did" burn, but it wasn't the villain here.

CC

OK, here's the facts on hydrogen. Hydrogen is a MAJOR industrial gas, usage of which is probably in the megatons/year category. It is routinely used from the very small scale to the very large scale. ONE company (Air Products) alone owns and runs over a thousand miles of hydrogen pipelines.

Every facet of safe usage is known and part of the established engineering literature. There is no magic needed to use it safely. It is a "known quantity" in science and engineering.

The ONLY part that is not in routine use is how one would put it into service in the hands of "non-experts" who need to fill their vehicles. One proposal is to make the process "robotic", i.e. the car and "gas pump" would be equipped with mechanisms that would make and test the "hookup" before gas is delivered.

But again, this sort of thing is well developed technology.

At one time we didn't know how to use gasoline safely, either, yet today it is routinely handled by millions of people.

The only real major unknown at this is how to produce hydrogen in the large quantities that would be needed.

CC

You're quite welcome.

I see in looking more closely at what I wrote that I did not cover "storage". All points along the production/use chain are again "known technology" (basically tanks and pipelines), except for "on-vehicle" storage. There are, at this point, many possibilities, but none which will yield the current cruise range of gasoline/diesel vehicles. The safest is probably metal-hydride, and the current most practical is probably ultra-high pressure tanks. It may be that folks will just have to "fill-up" more often.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.