Skip to comments.

High Risk Credit[Ron Paul]

House.gov ^

| 20 Aug 2007

| Ron Paul

Posted on 08/21/2007 11:34:38 AM PDT by BGHater

click here to read article

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first previous 1-20 ... 61-80, 81-100, 101-120 ... 161-164 next last

To: George W. Bush

Ron Paul does not think we could return to a full gold standard soon. He advocates an alternative currency that is gold/silver backed as way to begin moving toward sounder money.That's a good idea. Two different currencies circulating at the same time. LOL!

I see nothing wrong with the average American holding a few hundred dollars' worth of hard currency.

You can buy gold and silver right now. I heard they even sell it for fiat dollars!

BTW, I will point out that Reagan's 1980 platform in fact did call for a return to the gold standard.

IIRC, when Reagan left office on Jan 20, 1988, we were no more on the gold standard than when that platform was written.

So do you think that Reagan and his conservatives were just the "goldbugs of the world uniting"?

Perhaps he was throwing the goldbugs a bone?

The sorts of hidden inflationary erosion to which, for instance, the elderly are subject in their bank accounts and money market are a hidden tax on savings,

A gold standard would be deflationary. Do you think that would be a good thing?

This is also a key point in RP's appeal to young people who understand economics enough to know that it is them and their children who will bear the brunt of these policies for decades to come.

If these young people support a return to the gold standard, they still have a lot to learn about economics.

81

posted on

08/23/2007 6:43:07 AM PDT

by

Toddsterpatriot

(Ignorance of the laws of economics is no excuse.)

To: Toddsterpatriot

The Constitution does not stipulate that the currency be gold, or any precious metal.

The U.S. has never had a fully gold-backed currency and that is not the key point in Ron Paul's advocacy of offering a few forms of hard currency along with the fiat money from the Fed.

It's not either/or. It never was that way.

82

posted on

08/23/2007 6:43:25 AM PDT

by

George W. Bush

(Rudy: tough on terror, scared of Iowa, wets himself over YouTube)

To: Hail Spode

“Still, we need real money backed by something with intrinsic value.”

If you think this is such a great idea, then all you have to do is liquidate your money accounts and buy the commodity of choice. You can store that on your property or in a commercial storage location. If you have a need for dollars, then you can sell some of your commodity and take the dollars to the store. You really should consider this if you think commodity backed currencies are such a grand idea.

83

posted on

08/23/2007 6:50:22 AM PDT

by

DugwayDuke

(Ron Paul was for earmarks before he voted against them.)

To: George W. Bush

It's not either/or. It never was that way.So he wants $20 gold certificates to circulate alongside $20 fiat money?

Or does he want gold certificates exchangeable for fractions of an ounce?

84

posted on

08/23/2007 6:52:16 AM PDT

by

Toddsterpatriot

(Ignorance of the laws of economics is no excuse.)

To: Toddsterpatriot

That's a good idea. Two different currencies circulating at the same time. LOL!

What do you mean? Credit/debit cards, direct electronic bank transfers, Paypal are all competitors to ordinary bank checks and paper currency. And somehow the idea of, say, $40 billion to $100 billion in gold-backed hard currency is some radical threat?

You can buy gold and silver right now. I heard they even sell it for fiat dollars!

Then why not allow it again as a form of currency, like South African Krugerrands are?

IIRC, when Reagan left office on Jan 20, 1988, we were no more on the gold standard than when that platform was written.

I was simply pointing out that this is not an issue completely out of the blue for the Republican party as we have known it since the Reagan era.

A gold standard would be deflationary. Do you think that would be a good thing?

Merely saying it doesn't make it true.

If these young people support a return to the gold standard, they still have a lot to learn about economics.

Again, you deliberately misrepresent RP's position. Neither he nor anyone else is seriously envisioning an end to paper money. We are talking about a larger portion of U.S. dollars being in the form of hard currency of various commodity metals.

I think you're missing the mark by focusing on the minor issue of modest and incremental increases in hard currency. Given your outlook, what you should be far more concerned about is Ron Paul's campaign against the Federal Reserve system.

85

posted on

08/23/2007 6:52:45 AM PDT

by

George W. Bush

(Rudy: tough on terror, scared of Iowa, wets himself over YouTube)

To: Toddsterpatriot

Once again, you misrepresent the Constitution, and can point to no power in the Constitution authorizing Congress to issue paper money, that precise power having been considered and rejected in the Constitutional Convention.

As for the benefits of deflation, I reproduce a good summary of the issue (it’s not right about everything, but it enough good points in it to make it worthwhile):

Deflation: The Biggest Myths

By Jörg Guido Hülsmann

Posted on 6/11/2003

[Subscribe or Tell Others]

The prospect of deflation haunts the political and economic establishment in our western democracies. Their fears are understandable, at any rate from an economic point of view. Consider the following three basic propositions of monetary economics:

According to the first proposition, both the quantity of money and the price level are irrelevant for the wealth of a nation. Firms and households can successfully produce any quantities of consumers’ goods at any price level and with any nominal quantity of money. The ultimate springs of human wellbeing are savings, technology, and entrepreneurship – not money supplies and price levels.

According to the second proposition, while changes in the money supply do not affect the wealth of a nation in the aggregate, they change the distribution of resources among the members of society. In the case of an increasing money supply, for example, the first owners of the additional quantities of money benefit at the expense of all other money owners. Notice that these redistribution effects result not only from changes in the quantity of money, but from any changes in the supply of any good. There is a significant difference between money and all other goods only in a fiat money regime. This brings us to our third proposition:

A fiat money regime considerably facilitates the re-distribution of resources within society. It allows the owners of the printing press and their political and economic allies to enrich themselves far quicker and at much lower cost than any other producer in any other field. This explains why governments have for centuries sought to establish a paper currency. And it explains why, after they had achieved this goal in the 20th century, governments and their business allies set off on an exponential growth path. The welfare state has exploded in the 20th century, and Wall Street and the banking sector grew quicker than almost any other sector of the economy.

This would not have been possible on a free currency market, because nobody would accept banknotes the purchasing power of which depends on the whim of its producer. And indeed paper money has never existed in a truly free currency market.[1] It is essentially fiat money – money that the government imposes on its citizens. Paper money is protected through “legal tender” laws, which means that you and I can be forced to accept it as payment, even if we have contractually stipulated payment in other commodities. Moreover, in many countries paper money is shielded against its main competitors such as coins made out of precious metals through the tax code – sales taxes and capital gains taxes apply to these metals, but not to paper money. In short, paper money is monopoly money; it enriches the happy few at the expense of all others.

The deflation-phobia of our elites is therefore the rational reaction of those who profit from the privileges that our present inflationist regime bestows on them, and who stand to lose more than any other group if this regime is ever reversed in a deflationary coup. Perennial inflation is based on monopoly. Deflation brings in the fresh winds of the free market. True elites would welcome deflation for precisely this reason, because they owe their leadership positions exclusively to the voluntary support of other members of society. They have nothing to fear from deflation – a shrinking money supply – because their leadership is grounded on the useful entrepreneurial services they provide to their fellow citizens – services that would subsist through any changes in the money supply or in the price level.

But large parts of our present-day elites are “false elites” or “political entrepreneurs.” These men and women owe a more or less great amount of their income and decision-making power to legal privileges that protect them from competition and which enrich them at the expense of all other people. The fortunes of many political entrepreneurs are directly or indirectly attributable to the money monopoly of the Federal Reserve System. It is only because of this monopoly that the Fed could create a near boundless expansion of the money supply. And it is this inflation that in turn has financed a near boundless expansion of the activities of the federal and state governments, and of those who rely essentially on their lobbying effort with the Fed, rather than on the quality of their products, to reach and maintain leadership positions.

Political entrepreneurs are thus right to fear deflation. For deflation takes away the source of their illegitimate income and puts them finally back on equal footing with all other members of society, whose incomes are based on efforts and services provided in a competitive environment.

But these privileges can only survive because of widespread ignorance about the true character of deflation.[2] A closer look reveals that the case against deflation squarely rests on a litany of inflationist myths. To these we now turn.

Myth #1: You cannot earn a living and make profits when the price level falls

Most of our analysis will deal with deflation in the sense of a shrinking money supply. This case is most interesting from a political point of view, because few economists and laymen are ready to concede any benefits to deflation in this sense. But before we turn to this case, let us briefly examine the character of deflation in a somewhat different connotation, namely, in the sense of a decrease of the general price level. This type of deflation draws much less criticism than the other type, but it might be useful to deal with it first as a warm-up for out subsequent discussion.

Thus, is it true that one cannot earn a living and make profits when the price level falls? The answer is in the negative. Successful business does not at all depend on the level of prices, but on price spreads or, more precisely, on spreads between selling receipts and cost expenditure. But such spreads can exist and do exist at any level of prices, and they can exist and do exist even when there is a secular decline of prices. The essential reason is that entrepreneurs can anticipate declining prices, just as they can anticipate increasing prices. If they anticipate a future decline of their selling proceeds, they will bid down present prices of factors of production, thus assuring profitable production and paid employment for everyone willing to work. This is exactly what happened in the few periods of modern history in which deflation was not prevented through inflationist counter-measures.

For example, both the U.S. and Germany enjoyed very solid growth rates at the end of the 19th century, when the price level fell in both countries during more than two decades. In that period, money wage rates remained by and large stable, but incomes effectively increased in real terms because the same amount of money could buy ever more consumers’ goods. So beneficial was this deflationary period for the broad masses that it came to the first great crisis of socialist theory, which had predicted the exact opposite outcome of unbridled capitalism. Eduard Bernstein and other revisionists appeared and made the case for a modified socialism. Today we are in dire need of some revisionism too – deflation revisionism that is.

Myth #2: While falling prices are good, lacking aggregate demand is bad

This is a variant of myth #1. While the advocates of this myth concede the point that lower prices are advantageous from the point of view of consumers, they claim that there are manifest disadvantages from the point of view of producers. In particular, there would be few incentives to invest into any sort of business in an environment of shrinking prices. We have already rebutted this view by pointing out that the absolute future price level is irrelevant for profitable enterprise. The relevant factor is the possibility to realise a spread between selling proceeds and cost expenditure, and this possibility exists irrespective of the movement of the price level.

Now our anti-deflationist might come up with the following objection: profitable enterprise in times of falling prices presupposes that businessmen can bid down factors of production in anticipation of the event. If they are unable to bid factor prices down, they will not invest at all. QED.

But this argument overlooks that all resources are invested into some use at any point of time. Why are our farsighted entrepreneurs unable to bid the factor prices down? Clearly this is so either because the factor owners are not ready to sell them at the lower prices, or because other entrepreneurs offered slightly higher prices. In the latter case, there is clearly no lack of investment and productive activity. The factors in question are bought and sold – albeit at lower prices than would have been offered in inflationary times. And even in the former case, the factors are invested – they are invested in the “reserve stock” of the owner of these factors, and such a reservation demand fulfils a useful social function just as any other form of demand.

Myth #3: You cannot earn a living and make profits when the money supply shrinks

Human beings are able not only to anticipate a falling price level, but also the consequences of a shrinking money supply. Such anticipations will usually accelerate the deflationary process and make it reach the “rock bottom” of a stable money supply very quickly. Two cases need to be distinguished: A) the case of a fractional-reserve banking system operating on the basis of a commodity money such as gold or silver and B) the case of a paper money.

In case A, the supply of physical gold or silver can obviously not just vanish in thin air, and thus it remains to provide rock bottom in case of a deflation of fractional-reserve notes. Such a deflation usually starts when more and more people refuse to accepts these notes as payment, and it usually ends in a bank run, when even the present holders of the notes no longer wish to own them and rush to the issuing bank to redeem them in gold or silver. After the run, the money supply has often considerably shrunken because all fractional-reserve notes have disappeared from circulation. But the stock of metallic money remains and provides a rock bottom, below which the money supply cannot sink. There is no reason why this deflationary process should not be finished in a few hours or days. When it has ended, many banks will be bankrupt and many entrepreneurs will be bankrupt too, to the extent that they have financed their firms with debt rather than with equity. This explains of course why the present debt-financed establishment ferociously resists deflation. But it does not mean that production could not go on without them – in fact it can go on and will go on under new ownership.

In case B, there is no rock bottom to provide a stopping point to the deflationary process reducing the supply of a paper money. When people no longer wish to own a paper money and start selling it at any price, the result will be an ever declining purchasing power of this money, which in turn might convince even those who had bought that they better get rid of it, and the sooner the better. The result is a deflationary spiral: less willing owners – less purchasing power – less willing owners – less purchasing power and so on, until the paper money has completely vanished from circulation. Notice that this does not mean that the economy will necessarily be thrown back into a state of barter. What usually happens in such cases is that people start using other monies such as gold and silver coins, or foreign paper monies. The deflationary spiral therefore has the healthy effect of replacing an inferior sort of money – inferior from the point of view of the money users – with superior money. Again, there is no reason why this process should not be completed in a few days. And there is therefore no reason to expect that production will not resume very quickly under new ownership.

Myth #4: Deflation entails slower economic growth than inflation

Some champions of inflation concede that production can go on after a deflation, and possibly even in the midst of a deflation. But they claim that economic growth will be seriously curtailed by the necessary adjustments, to the point that it would have been preferable to avoid the deflation through inflation – or as they say, reflation.

It is difficult to discuss such claims in the absence of a commonly agreed-upon definition of economic growth. But the following consideration nevertheless applies: The problem of adjusting to deflation in the sense of a shrinking money supply is inherently a short-run problem. It is a problem of identifying those investment projects that are most profitable (and thus most socially beneficial) under the new conditions that deflation has brought into being. In particular, deflation in the worst of all circumstance induces businessmen and factor owners to hold back with their assets to avoid wasting them in any fancy venture. Deflation is therefore inherently sober, prudent, and financially conservative.

By contrast, inflation constantly lures capital into investment projects that do not find the spontaneous support of other members of society – capitalists, workers, and customers – but which are feasible only because they are financed, directly or indirectly, with money from the printing press. The most glaring example is the welfare state, which can be financed, not because there is any prospect of future returns, and not because it attracts a sufficient amount of voluntary donations, but solely because it is backed up with an ever-increasing amount of debts, which one day will be paid with new money from the printing press. This consideration applies quite apart from the fact, stressed by the Austrian economists, that inflation can induce inter-temporal misallocations of capital.

Given the enormous waste that goes in hand with inflation, it is not farfetched to assume that deflation will spur economic growth both in the long run and in the immediate run, by any definition of growth that emphasises the value scales of the individual members of society, rather than some arbitrary criterion of social justice.

Myth #5: Deflation is particularly burdensome for lower-income groups

The main asset of relatively poor people is their labour, and labour is a relatively non-specific asset, which means that it can be used in many branches of industry. If a worker can no longer be employed in his present position, it is therefore always possible for him to find new employment elsewhere, even though at a lower market price. By contrast, relatively rich people typically derive a larger part of their income from financial assets. Ultimately these assets relate to the ownership of capital goods, which in turn are highly specific assets – they can very often be used only in exactly the way in which they are presently used. If this use is no longer profitable, there will be a more or less dramatic drop of their market price, often to scrap value.

It follows that deflation affects lower-income groups less than higher-income groups.

Myth #6: Deflation destroys the credit of the state

It is true that deflation – especially deflation in the sense of a contraction of the money supply – will make it impossible for a government to ever pay back public debts. And it is also true that it will then for some time be impossible for the government to obtain new credits.

But it is a myth to believe that we have to wait for deflation to bring about this result. Public debts are on an exponential growth path and no official even talks about paying them back. Fact is that our western governments are already on a slippery slope that will inevitably end up either in hyperinflation or in state bankruptcy. It is just a question of time until they will have destroyed their credibility all on their own – deflation would merely speed up this process.

Let us also notice that there are potentially beneficial effects associated with state bankruptcy. In particular, governments would again be dependent on obtaining revenue mainly through taxation, and that puts a healthy break on their expansion path.

Myth #7: Deflation creates unemployment

Unemployment of a factor of production comes about only in two cases: A) if the owner of the factor is not willing to rent it out at the price offered to him, or B) if the law prevents him from doing so. It is therefore not true that declining wage rates bring about unemployment by any sort of inner necessity. People are not just unemployed. They choose not to work for an employer under the (pecuniary and non-pecuniary) conditions offered to them. Now it is clear that no sane person will accept to work for somebody else if the wage rate does not allow him to survive anyway. But this is not the case in a deflation. Remember that here all prices fall, and thus the decline of wage rates is compensated by a parallel decline of the prices for consumers’ goods. It is true that there might not be in all cases an exact parallel between wage rates and the prices of consumers’ goods, but any deviations will be temporary only and can easily be bridged for some time with the assistance of family, friends, and charitable institutions.

Involuntary unemployment might arise in a deflation only if the latter is combined with minimum wage laws, which prevent the worker from offering his services at lower rates. But clearly this unemployment does not result from deflation, but from the minimum-wage laws, which infringe on the freedom of association.

Myth #8: Deflation entails unequal and arbitrary burdens for the citizens

It is true that deflation involves heavy burdens for many individuals. Just consider the fact that today the great majority of U.S. household have incurred considerable liabilities, usually in the form of real estate mortgages. If a contraction of the money supply sets in, household incomes will decline and it will be impossible to pay back these liabilities. It will then be necessary o renegotiate debts, and some individuals will have to file bankruptcy. It is also true that deflation has unequal consequences for the individual citizens. Some will prosper in a deflationary environment more than they would have prospered in the present inflationary regime, and others will fare worse. Finally it is true that these re-distributions are often difficult to square with one’s notions of what is just and unjust.

So where is the myth? The myth consists in the belief that only deflation entails unequal and arbitrary burdens for the citizens. The truth is that the present inflationist regime is no less re-distributive and arbitrary than any deflation could possibly be. Inflation constantly re-distributes income from people who offer genuine services to people who happen to enjoy political alliances with the masters of the printing press.

Even if inflation is used “only” to prevent an impending deflation, these arbitrary and unequal redistribution effects cannot be avoided. The very least thing we could say, therefore, is that deflation is certainly not more unjust than inflation. But as well shall see further down, there are in fact very tangible benefits to be derived from deflation that make it actually preferable to continued inflation. But before we come to discussing this point, let us briefly deal with another issue:

Myth #9: It will take decades to settle deflation-induced legal disputes

Have we not been too over-optimistic in assuming that deflation might be a matter of a few hours or days? Is it not rather likely that deflation will upset a great number of long-term contracts, from mortgage contracts over industrial bonds to real estate leases? And is it not rather likely that it will take the courts some twenty years or so to sort out all the different claims and counter-claims?

It is true that, while the adjustment of the price structure to the new deflation-created conditions might take just a few hours or days (but could take much longer if government interventions hamper the adjustment process), the settlement of legal disputes could involve much longer times periods. But based on the empirical evidence it is certainly exaggerated to assume that more than a few months would be needed.

Consider the German deflation that set in after the bankruptcy of the Darmstädter Bank on July 13, 1931, and which lasted some two years. The crisis very quickly jeopardised the liquidity, not only of the banking sector, but also of virtually all other branches of German industry. Contractual relations were upset on a large scale, and thus it not only came to bankruptcies on an unprecedented scale, but also to a great number of revisions of previous contracts, both inside and outside of the courts, and to payment moratoria. Unemployment rose to almost 7 million, production stopped in many firms, salaries and wages plummeted, as did all other prices. The radical drop of real estate prices jeopardised the mortgage business, as well as financial titles backed up with mortgage claims.

How were these problems handled? Well, the unemployment problem was not handled at all, because government had created the conditions under which unemployment was inevitable: unemployment insurance and minimum wage laws. The result was social upheaval and twelve years of National Socialism.

But the problems relating to claims resolution were handled rather quickly and efficiently, partly because the German courts had, in the wake of the hyperinflation of 1923, gained some experience in dealing with dramatic changes in the purchasing power of money. In a great number of cases, the disputes never made it into the state courts, but were settled in private arbitration. The remainder was settled in the state courts or dealt with in a series of four emergency laws, the last of which was voted in parliament on December 8, 1931. Thus, a few months after the deflation had set in, all essential legal tools and institutions were in place and operated fairly efficiently.

There is no reason to assume that things would be handled less efficiently in the present-day United States, especially if legal scholars turn their energies into analysing the problems that are here at stake.[3]

Myth #10: Deflation confers no positive net benefit

Granted that a heavy contraction of the money supply is merely on equal footing with increases of the money supply when it comes to the distribution of burdens among the citizens. But is it not the case that we have pretty well adjusted out behaviour to the present inflationary environment, where as letting deflation happen would impose on us a re-adjustment? Even if this adjustment is only a temporary affair, still it involves costs for all members of society. So what are the benefits of deflation that could prompt a responsible citizen to endorse it, apart from the uncertain prospect of being on the winners’ side in the short-run zero-sum redistribution process that deflation entails? Here the following consideration comes into play.

First of all, deflation is a very efficient mechanism to speed up adjustment to new circumstances in the wake of a major financial crisis. The reason is, as we have noticed above, that deflation affects the prices of factors more than it affects the prices of consumers’ goods. As a consequence, deflation increases the spread between selling receipts and cost expenditure – in other words, the interest rate – and thus creates powerful incentives for increased savings and investments.

Second, and equally importantly, deflation is a one-time process that however has the potential to destroy the very institutions that produce inflation on a perennial basis, in particular, fractional-reserve banks and fiat money producers (“central banks”). The destruction of these institutions eliminates the “advantage at the margin” enjoyed by liability finance as compared to auto-finance. In other words, economic and social power is taken away from the Fed and the banks, and returned into the hands of individual citizens. Firms will operate on a far higher equity basis than before, and households will, in more cases than before, first save and then buy a home. Furthermore, the destruction of the inflation machine will destroy the main financial engine of the welfare state. Governments will henceforth have to obtain their resources exclusively through taxation, which is subject to far greater social control than the unworthy stealth method of gaining resources by inflating the money supply.

Myth #11: Letting deflation happen is “passivism”

In the light of our foregoing discussion, it is clear that letting deflation happen must not be simply equated to an apathetic resignation before the power of mysterious forces and blind market mechanisms. Deflation can fulfil extremely useful social functions and those who cherish individual liberty and the sanctity of private property are on good grounds in consciously striving to let deflation run its course. If anything, it is letting inflation happen that amounts to apathetic resignation – resignation that is before the power of a money monopoly that thrives on ignorance, and which benefits political networks at the expense of capitalistic civil society.

86

posted on

08/23/2007 7:06:08 AM PDT

by

Iconoclast2

(Two wings of the same bird of prey . . .)

To: DugwayDuke

Duke that is a pretty reasonable formula for preserving existing wealth, but it does not speak to the problem of wages constantly losing value (and tax brackets creeping up).

Let’s say I was saavy enough and had time and space enough to buy and sell commodities with my monthly paycheck savings. The amount of commodities I could by each month will continually go down unless my wages kept increasing with inflation. For the last twenty years, wages have not tended to to that, and it is getting worse not better.

So-called “rising living standards” for the last twenty years or so are a result of kicking mom out into the workplace and making her a taxpayer too while the kids are raised in daycare by workers making near minimum wage. This is a formula for societal collapse IMHO, but big government and big business both love it.

When I was a kid, my allowance may have only been 10 pennies, but I knew a penny would buy 1 piece of bubble gum. That was my “commodity”. I remember when it went up to two pennies. Now it is at least a nickel, and the gum is not as good. In terms of bubble gum, the buying power of the dollar has lost 80% of its value in my life time. That’s a problem. The answer is an honest dollar whose value is constant, not asking every American to become a commodities trader.

To: Toddsterpatriot

So he wants $20 gold certificates to circulate alongside $20 fiat money?

So he wants $20 gold certificates to circulate alongside $20 fiat money?

Of course. And it would work to stabilize your buying power. And such currency could actually be profitable for the government to issue. You could offer currencies with state themes or sports team themes or Christian or environmental themes. Much like what we do with special and commemorative stamps. However, stamps' face value deflates pretty fast. a hard currency doesn't because it has intrinsic value and is often desired as a keepsake or nestegg or simply for its beauty and symbolism of our country and its values.

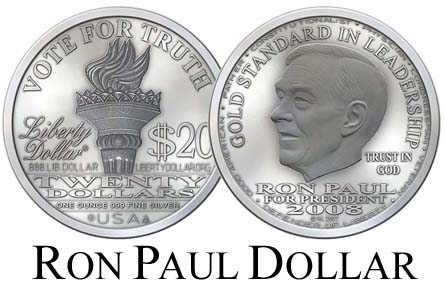

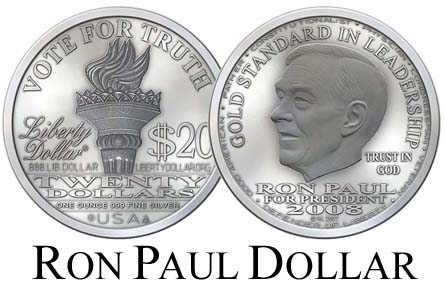

For an idea of what such currency would be like, notice the picture at the right. They offer coins in $1, $20, $1000 (copper, silver gold) with Ron Paul's likeness. Of course, a genuine mint coin would be classier and less commercial.

I know you're just lusting after a Ron Paul $1000 gold coin of your very own! LOL.

Tell me, would you like it any better if we agreed to put Mitt or Fred on those coins? Or President Reagan? Or a coin that commemorates the victims of 9/11 or the bravery and service of our troops? Those are all fine too. Really.

88

posted on

08/23/2007 7:11:51 AM PDT

by

George W. Bush

(Rudy: tough on terror, scared of Iowa, wets himself over YouTube)

To: Iconoclast2

Once again, you misrepresent the Constitution,You mean the Federal government is the same as the states?

and can point to no power in the Constitution authorizing Congress to issue paper money, that precise power having been considered and rejected in the Constitutional Convention.

Congress has the power: To coin money, regulate the value thereof

If you want to make the argument that they can produce fiat coins but not fiat bills, go for it.

As for the benefits of deflation

That's funny. The Japanese had 15 years of the benefits of deflation. They still haven't recovered.

89

posted on

08/23/2007 7:19:07 AM PDT

by

Toddsterpatriot

(Ignorance of the laws of economics is no excuse.)

To: Toddsterpatriot

If you think that Federal Reserve Notes are “coins”, why should we even bother to have a Constitution? Really, this is like Alice in Wonderland:

‘When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said, in a rather scornful tone, ‘it means just what I choose it to mean, neither more nor less.’

‘The question is,’ said Alice, ‘whether you can make words mean so many different things.’

‘The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be master – that’s all.’

* * *

And as for Japan, they still haven’t recovered (haven’t they?) because the government protected the zombie banks and the zombie borrowers. Someone who is ostensibly interested in a Free Republic, ought not to mischaracterize failures of government as failures of a free market.

90

posted on

08/23/2007 7:34:42 AM PDT

by

Iconoclast2

(Two wings of the same bird of prey . . .)

To: Iconoclast2

If you think that Federal Reserve Notes are “coins”,If you think the Constitution allows a $20 fiat coin but not a $20 fiat FRN, say so.

Really, this is like Alice in Wonderland:

Said the goldbug.

91

posted on

08/23/2007 8:05:52 AM PDT

by

Toddsterpatriot

(Ignorance of the laws of economics is no excuse.)

To: Toddsterpatriot

I don’t know what a “fiat coin” is, but yes, I do think that the Constitution REQUIRES gold and silver coin as money, with some reasonable latitude to adjust the weights in the coin. Going all the way to zero, however, would not be a reasonable interpretation of the Constitutional power, and would not be allowed by any Supreme Court Justice faithful to the basic idea of the Constitution.

It may interest you to know that this question—the Constitutional interpretation of the “coin money” phrase—has as far as I know, not been squarely decided by the Supreme Court. At least one petition for writ of certiorari has been rejected. Here was some of its arguments:

* * *

[Beginning with a quote from the Federalist Papers]

The Federalist Papers (No. 44 (Madison) (Modern Library ed. at 290-291)):

The extension of the prohibition to bills of credit [this being the history of the Constitutional Convention that refutes any claim Congress has power to issue paper money] must give pleasure to every citizen, in proportion to his love of justice and his knowledge of the true springs of public prosperity. The loss which America has sustained since the peace, from the pestilent effects of paper money on the necessary confidence between man and man, on the necessary confidence in the public councils, on the industry and morals of the people, and on the character of republican government, constitutes an enormous debt against the States chargeable with this unadvised measure, which must long remain unsatisfied; or rather an accumulation of guilt, which can be expiated no otherwise than by a voluntary sacrifice on the altar of justice, of the power which has been the instrument of it. ... The power to make any thing but gold and silver a tender in payment of debts, is withdrawn from the States, on the same principle with that of issuing a paper currency. [Emphasis supplied.]

Unlike the prohibitions on the states contained in the Art. I, s. 10, cl. 2 and cl. 3, which begin with the words “No State shall, without consent of Congress,” the prohibitions contained in the first clause are absolute. Edwards v. Kearzey, supra, 96 U.S. at 604, 607. Gunn v. Barry, 82 U.S. (15 Wall.) 610, 623 (1872). Indeed, the framers of the Constitution expressly considered and rejected proposals to allow exceptions to the monetary prohibitions with the approval of Congress. 2 M. Farrand ed., The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 (Yale Univ. Press, 1966), pp. 144, 169, 187, 439 & n.14. Congress, therefore, has no power to authorize or permit — directly or indirectly — any state to violate the prohibitions contained in Art. I, s. 10, cl. 1, especially the monetary prohibitions.

A fortiori, the federal government cannot, by exceeding its own monetary powers under the Constitution, authorize the states to resume the practices that Art. I, s. 10, cl. 1, was intended to prohibit. Two wrongs do not yet make a right.

Whatever may have been the situation at certain times in the past, there is nothing in federal law today to excuse strict enforcement of Art. I, s. 10, cl. 1. Unlike Civil War greenbacks or Federal Reserve notes prior to 1971, there is no sense in which current paper dollars can be said to be a temporary or functional equivalent to gold coin. Ownership of gold is again lawful, and Congress has provided for legal tender gold and silver coins. Since one of them is but little debased from the money expended by the plaintiff in 1966, the Constitution, common sense and simple fairness all direct that it be the medium of reimbursement.

Accordingly, Art. I, s. 10, cl. 1, should now be enforced to bar a state, or any instrumentality thereof, from compelling an unwilling private creditor to accept anything other than gold or silver coin in payment of its obligations. This does not mean that a state cannot enter into voluntary contracts that provide — expressly or by implication — for payment or repayment in Federal Reserve notes. For example, persons who purchase state or municipal bonds, paying for them in paper money and accepting an interest rate based on the use of paper money, cannot later legitimately claim that they are entitled to be repaid in gold or silver coin. In that situation, the contract is voluntary and the use of unlimited paper money a mutually shared assumption. The constitutional prohibition aims at the unfair and coercive imposition of depreciated paper. That is the situation in the case at bar.

* * *

Of course, it is unlikely that the poor specimens who presently inhabit our Supreme Court (other than, perhaps, Clarence Thomas, who has some lingering respect for the historical meaning) would enforce the plain language. Even Judge Bork told the Senate Committee reviewing him that he would not do so.

* * *

So you don’t work for the government? Do you work for a bank, or a mortgage company, or some heavily leveraged entity that depends on the debt-based money system? I really can’t see why the plain language of the Constitution is so difficult to understand.

92

posted on

08/23/2007 9:37:09 AM PDT

by

Iconoclast2

(Two wings of the same bird of prey . . .)

To: Iconoclast2

I don’t know what a “fiat coin” is, but yes, I do think that the Constitution REQUIRES gold and silver coin as moneyThe only proof you've shown put that restriction on states, not the Federal government.

with some reasonable latitude to adjust the weights in the coin. Going all the way to zero, however, would not be a reasonable interpretation of the Constitutional power

So the Constitution said "Congress has the power: To coin money, regulate the value thereof", but not to zero gold? I don't see any limit to their power to "regulate the value thereof". Maybe you have a post (less than 10,000 words please, LOL!) that shows the limit to that power?

So you don’t work for the government?

No.

Do you work for a bank, or a mortgage company, or some heavily leveraged entity that depends on the debt-based money system?

Do you work for a company that would benefit from long term deflation?

I really can’t see why the plain language of the Constitution is so difficult to understand.

I may have missed it in all your data dumps, did you ever post the part of the Constitution that says the Federal government must issue gold backed money?

93

posted on

08/23/2007 9:47:05 AM PDT

by

Toddsterpatriot

(Ignorance of the laws of economics is no excuse.)

To: Iconoclast2

I don’t know what a “fiat coin” is, That would be a coin that has a face value of $20 but doesn't have $20 worth of gold or silver in it.

94

posted on

08/23/2007 9:51:11 AM PDT

by

Toddsterpatriot

(Ignorance of the laws of economics is no excuse.)

To: BGHater

Fiat money is only a problem if one country inflates and the others don't.

Since all countries are now inflating >10%, their currencies fall together.

The only way around that is to hold gold (until the guvmint takes it away from you ala 1934).

To: Toddsterpatriot

This is not rocket science. Here is yet another explanation (footnotes omitted, from yet another Harvard lawyer, Robert K. Landis):

* * *

We often hear pundits and politicians talk about “strict construction.” This is a phrase introduced as a campaign slogan by Richard Nixon. It’s a sort of code, signifying a “conservative” — as opposed to an “activist” — judicial philosophy. It has no real legal meaning, but is popularly understood to refer to interpreting and applying the Constitution according to the plain meaning of the words and the original intent of the Founders.[5]

The reality is, particularly with respect to its monetary provisions, the Constitution is a dead letter. There is not a “strict constructionist” anywhere near a position of real power and influence in Washington. In the words of Rep. Ron Paul, a tireless champion of sound money and one of the authors of the Minority Report[6]:

Perhaps no important document is held in less regard in Washington, D.C., than the United States Constitution. In fact, the attitude of many Congressmen and government officials toward the Constitution consists of giving lip service to it by refusing to take it seriously. It is considered obsolete, written for agrarian economies; and our highly technological society has supposedly moved far beyond its limits. It is to be referred to only when convenient and ignored when inconvenient.

This official disregard goes with the institutional territory. As the Minority Report observed (p.243):

The present monetary arrangements of the United States are unconstitutional-even anti-constitutional-from top to bottom. / The Constitution actually says very little about what sort of monetary system the United States ought to have, but what it does say is unmistakably clear.

They got that right. Consider, for example, what the Constitution says about federal power to issue paper money and establish a central bank:

ARTICLE I, Section 8. The Congress shall have Power * * *

Clause 2: To borrow Money on the credit of the United States * * * .

ARTICLE I, Section 9.

Clause 7: No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law * * *.

Notice anything odd here?

That’s right, it doesn’t say anything about paper money, let alone central banking.

With respect to central banking, the Minority Report observed (pp. 261-262):

By a strict interpretation of the Constitution, one of the most unconstitutional (if there are degrees of unconstitutionality) of federal agencies is the Federal Reserve. The Constitution grants no power to the Congress to set up such an institution, and the Fed is the major cause of our present monetary problems. The alleged constitutional authority stems from a loose and imaginative interpretation of the implied powers clause.

This raises a point that is critical to interpreting the Constitution, strictly or otherwise: what the Constitution doesn’t say is just as important as what it does say. That’s because every power exercised by government has to have a root authorization in the Constitution. Any power that is not delegated is withheld. That’s the genius of the limited state conceived by the Founders.[7]

Strict construction, anyone?

What Part of “No Authority” Don’t They Get?

With respect to the issuance of paper money, the lack of authority is even more egregious, because this was something the Founders specifically considered, and knowingly rejected.

Here it’s helpful to recall that the Constitution did not spring whole from the Founders’ foreheads at the Philadelphia Convention in 1787. It was a carefully studied — and extensively debated — successor to an original charter known as the Articles of Confederation.

The Articles had been adopted ten years earlier, shortly after the outbreak of the Revolution, and had formally governed relations among the states since 1781. In today’s terms, the Articles were something of a cross between a customs union and a multilateral treaty of friendship, navigation and commerce among sovereign states. They provided for a rather weak central governance committee known as Congress.

This earlier charter had proved inadequate in a number of respects. The Constitution was intended to correct its deficiencies. So if we’re interested in understanding the Founders’ intent with respect to particular provisions of the Constitution, it is relevant to consider what it was they were trying to fix.

Have a look at the predecessor version of the language quoted above relating to paper money, as set forth in the original Articles (emphasis supplied):

IX. * * * The United States in Congress assembled shall have authority * * * to borrow money, or emit bills on the credit of the United States * * * .

Although the words used in these old documents carry slightly different meanings today, their original meaning should be clear enough to a “strict constructionist.” We see here that the Articles had given Congress the explicit power to issue paper money, so-called “bills of credit.”[8] The states also had that power, by virtue of the fact that the Articles nowhere said they didn’t: the Articles were emphatic that any power not specifically delegated to the Congress was retained by the sovereign states.

During the American Revolution, both Congress in the notorious Continental currency[9], and the several states in a profusion of paper currency and debt certificates[10], had duly exercised this power. The result was a monetary disaster.[11] The delegates, who had come to Philadelphia from their home states that were suffering varying degrees of financial and economic distress, were determined to implement a lasting monetary reform.[12]

And one of the first things they did in this reform document, right there in Article I, was take away from Congress the power to issue paper money, by deleting the language “or emit bills.”[13]

Strict construction, anyone?

A Money Measured by Weight

There’s more.

Have a look at what the Constitution says about what money is permissible.

ARTICLE I, Section 8. The Congress shall have Power * * *

Clause 5: To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the standard of Weights and Measures * * *

ARTICLE I, Section 10.

Clause 1: No State shall * * * coin Money; emit Bills of Credit; make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts * * * .

Here we see the heart of the monetary provisions in the Constitution.

In clause 1 of Section 10, it’s pretty clear what’s going on, to judicial activist and strict constructionist alike.

First, we see that the states lost their power to coin money.

Second, we see that the states were explicitly denied the power to issue paper money.

Third, we see that the states were denied the power to make anything but gold and silver coin a legal tender — which would include, by the way, anything issued by the federal government.[14]

It’s clause 5 of Article I that seems to offer some wiggle room to the champions of paper money. We see that money is something that’s coined, not printed, and that, as such, it is properly lumped in with weights and measures. But doesn’t the power to coin money suggest some sort of “implied power” to print paper as well?

No. Not, at any rate, to anyone concerned with the plain meaning of the words:[15]

Coins are pieces of metal, of definite weight and value, thus stamped by national authority. Such is the natural import of the terms “to coin money” and “coin;” and if there were any doubt that this is their meaning in the Constitution, it would be removed by the language which immediately follows the grant of the “power to coin” authorizing Congress to regulate the value of the money thus coined, and also “of foreign coin,” and by the distinction made in other clauses between coin and the obligations of the general government and of the several states.

What about that language, “regulate the value thereof”? Doesn’t that give Congress carte blanche to do whatever it wants regarding our money?

No. Not, at any rate, to anyone viewing money as metal with weight and fineness, which is to say, anyone present at the Constitutional Convention, or anyone who now fancies himself a “strict constructionist.”[16]

The power of regulation conferred is the power to determine the weight and purity of the several coins struck, and their consequent relation to the monetary unit which might be established by the authority of the government - a power which can be exercised with reference to the metallic coins of foreign countries, but which is incapable of execution with reference to their obligations or securities.

And that’s all there is. That’s the sum total of the core monetary provisions of the Constitution.[17] In these few words, men of courage and genius gave us a charter of monetary freedom never equaled before or since.[18]

Strict construction, anyone?

96

posted on

08/23/2007 10:08:40 AM PDT

by

Iconoclast2

(Two wings of the same bird of prey . . .)

To: Iconoclast2

We see that money is something that’s coined, not printed, and that, as such, it is properly lumped in with weights and measures.I don't see a Constitutional problem with eliminating FRNs and replacing them with coins. The coins will be less convenient and still won't contain gold or silver, but if that's what we have to do to make the goldbugs happy, then I guess we should do it.

97

posted on

08/23/2007 10:14:33 AM PDT

by

Toddsterpatriot

(Ignorance of the laws of economics is no excuse.)

To: Toddsterpatriot

For God’s sake, how can you square coins without gold or silver with the Constitutional idea that nothing but gold or silver coin is lawful money?

Under your approach to interpreting the Constitution, if we outlaw everything except toy guns, that’s just fine, because we still have the right to bear arms—it’s just that they are made out of plastic and can’t kill anyone.

98

posted on

08/23/2007 10:20:20 AM PDT

by

Iconoclast2

(Two wings of the same bird of prey . . .)

To: Iconoclast2

For God’s sake, how can you square coins without gold or silver with the Constitutional idea that nothing but gold or silver coin is lawful money? Either Congress has the power to regulate the value of money or they don't.

99

posted on

08/23/2007 10:22:09 AM PDT

by

Toddsterpatriot

(Ignorance of the laws of economics is no excuse.)

To: Toddsterpatriot

All too true. There is very little that limits what the federal government can do outside any state, isn't there? Said another way, so long as the activity is within its region, dominion, or area or jurisdiction, it can do what it wants, or Congress can legislate what they want and the federal government carries it out, and people have to obey. On the subject of money, so long as the federal government does not cause things other than gold and silver coin to pass as a Tender in the Payment of Debts within any State (and I agree they are not), the federal government is technically in the clear. Correct?

Do you have a problem with anything I wrote above? Are we in agreement or not?

100

posted on

08/23/2007 10:47:26 AM PDT

by

Jason_b

(Click jason_b to the left here and read something about People v. De La Guerra 40 Cal. 311)

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first previous 1-20 ... 61-80, 81-100, 101-120 ... 161-164 next last

Disclaimer:

Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual

posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its

management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the

exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.

FreeRepublic.com is powered by software copyright 2000-2008 John Robinson

So he wants $20 gold certificates to circulate alongside $20 fiat money?

So he wants $20 gold certificates to circulate alongside $20 fiat money?