Something else former-President Clinton and former-VP Gore cost us.

Posted on 07/04/2007 12:58:46 AM PDT by anymouse

"'La force motrice' of Reusable Launcher Development: The Rise and Fall of the SDIO's SSTO Program, From the X-Rocket to the Delta Clipper"

Introduction.

NASA commissioned me to document the development of the X-33 in March of 1997. The X-33 is an advanced technology demonstrator vehicle intended to flight test technologies deemed critical for eventually building a reusable single-stage-to-orbit rocket transport. Those technologies include a metallic thermal protection system, an aerospike engine, and composite cryogenic hydrogen tanks. As part of the history project, I chose to write about the SDIO's SSTO Program as a predecessor to the X-33, even though two different agencies undertook the two programs. Later, when I write the "official" history of the X-33 for NASA, a comparison of the NASA and SDIO programs will prove fruitful. The story of the SDIO SSTO Program is the core of this talk.

As for the French expression in the title of this talk, "la force motrice," I first encountered it in Paris at the Center for Research in History of Science and Technology (CRHST), which was then headed by Dominique LePestre. LePestre led the group in a discussion of "la force motrice," the single, most important causal or determining factor. To LePestre, finding the "force motrice" (or what he called in English "ze driver") for a given historical incident provided vital insight into how things work.

I, however, continued to enjoy that past time of American historians, attributing multiple causalities to historical evolution and outcomes. More recently, the NASA History Office, in conjunction with the Air Force, the National Air and Space Museum, and other entities hosted a one-day symposium on the history of launch systems. The original organization of the symposium followed the course of launcher technology from its Cold War origins, to its adoption for civilian (mainly NASA) uses, and finally to its commercial application. In other words, the symposium used the idea of a single, most important causal factor (or "force motrice") to organize the papers presented.

In this talk, I want to consider which of those factors-Cold War, civilian use, commercial application--has been the "force motrice" behind the search for reusability during roughly the last ten years. First, though, I want to distinguish between expendable launch vehicles (ELVs) and reusable launch vehicles (RLVs). ELVs are ammunition. Missiles are essentially ammunition. They are artifacts of military defensive and offensive systems and are designed to be used a single time.

Because they have only one chance at success, missiles are expensive. The higher missile and launch costs go, the more backups are needed, driving costs even higher. Ultimately, too, these high launch costs keep down the number of launches, especially for commercial customers.

RLV's are transportation, like a railroad train or an airplane. They can launch not once, but several times, and can fly again shortly after landing. RLVs also use smaller flight and operational teams. Costs decline, because one no longer needs to build and qualify a new rocket for each launch. "Launch" becomes an antiquated term; "take off" and "land," words used to describe airplane operations, are more appropriate. In fact, making RLVs that have the characteristics of airplane operations is the essence of the revolution in thinking behind reusable launchers, that is, true spaceships.

Today, I want to use the story of the SDIO SSTO Program to draw some conclusions about what has been the driver, the "force motrice," behind the search for reusability. The search for reusability as a technological solution to the problem of rocket-powered space flight can be traced to the period before World War II. Subsequently, several programs, such as the military's Aerospaceplane, the Dyna-Soar (X-20), and the National AeroSpace Plane (NASP, or X-30), have sought to realize a reusable launch vehicle.

Reagan Space Initiatives.

Rather than follow the technological trail from Goddard "stratosphere plane" to the X-33, I'll begin with the presidency of Ronald Reagan. Reagan was the last of the Cold War Presidents. Under Reagan, following the successful flight of the Shuttle Columbia in 1981, space policy took on a new level of national importance, one the country had not seen since the Kennedy Administration and the mission to land an American on the Moon by 1970. Not only did the Reagan Administration initiate a plethora of new programs, most of which rode on the euphoria stimulated by the apparent success of the Space Shuttle, but Reagan's space policy measures had a major impact on the use of space and on access to space that continues to be felt even today.

Among the major initiatives of the Reagan Administration was the space station, announced during the 1984 State of the Union address. Reagan attempted to emulate the drama and boldness of President John Kennedy's challenge to land an astronaut on the Moon by the end of the decade. "Tonight," he announced, "I am directing NASA to develop a permanently manned space station and to do it within a decade. A space station will permit quantum leaps in our research in science, communications, in metals, and in lifesaving medicines which could be manufactured only in space."

Later, only days after the Challenger disaster, during his 1986 State of the Union Address, Reagan declared: "We are going forward with research on a new Orient Express that could, by the end of the decade, take off from Dulles Airport, accelerate up to 25 times the speed of sound attaining low Earth orbit, or fly to Tokyo within two hours." The media took up Reagan's Orient Express designation, but the actual program name was the National Aero-Space Plane (NASP or X-30). The proposed NASP vehicle would be capable of both suborbital high-speed flights from one point on the ground to another and flights into orbit. Indeed, the NASP vehicle, if built, would have been not just the fastest aircraft in the atmosphere, but also the country's first reusable single-stage-to-orbit vehicle.

Another major Reagan space program was the Strategic Defense Initiative, run by a new government agency (the SDIO) under the Department of Defense. Reagan announced the creation of the SDI in a speech delivered on March 23, 1983. The Strategic Defense Initiative, as the space-based defense program was called in National Security Decision Directive 119, signed January 6, 1984, was set up between 1983 and 1985. It became the Pentagon's largest single research and development program.

Finally, further far-reaching Reagan space initiatives sought to promote the commercialization of space. Space commercialization has come to mean three different types of activity. In one such activity, the federal government provides services to the commercial sector.

Examples would be placing commercial payloads on the Shuttle or the Space Station. Another meaning of space commercialization is privatization, in which companies take over federal assets or functions. Two examples are the privatization of Shuttle maintenance and the failed attempt to privatize Landsat. In addition, there is a broader vision of space industrialization that is part of a more general quest to expand all human activity into space. NASA jumped on the space commercialization bandwagon in 1984, when it established the Office of Commercial Programs, then issued in 1986 its "Guidelines for United States Commercial Enterprises for Space Station Development and Operations."

The commercialization of space would not be complete without the launching of payloads (commercial and governmental) on privately owned launchers. The Commercial Space Launch Act of 1984 specifically sought to promote the creation of a U.S. private launch industry. Reagan tax policies, combined with an upturn in the economy, created a financial atmosphere that favored speculative ventures. Some speculative investment found its way into the private launcher industry.

Origins in the Citizens' Advisory Council on National Space Policy

The Reagan Administration not only made space a national priority, but commercialized and militarized it more than any previous administration. Although the SDIO SSTO Program easily fit into the Reagan space policy (technologically like the reusable single-stage-to-orbit NASP and politically as a launcher of SDI payloads), the idea for the program began not within the SDIO nor any other government agency, but within what we might call the space movement. The critical group called itself the Citizens' Advisory Council on National Space Policy and had been founded by Jerry E. Pournelle.

Pournelle, known best as science fiction writer and (later) as a Byte computer magazine editor, also was a longtime board member of the L-5 Society, and at one time its de facto co-president. In the 1970s, he co-authored a book, The Strategy of Technology, which contained a chapter on "Assured Survival," a strategic substitute for Mutual Assured Destruction. Pournelle also had been associate director of operations research at North American Rockwell's Space Division, as well as president of the Pepperdine Research Institute. In addition, he was a speech writer for California Governor Ronald Reagan.

As for its role in the Reagan transition team, Pournelle described the Citizens' Advisory Council in 1989 as "an entity created as part of the Reagan Transition Team structure, but kept around because Mr. Reagan and some of his people found our reports useful." Despite some overstatement of the Citizens' Advisory Council's political importance, Pournelle's group did manage to deliver its reports to the President during the Reagan Administration.

Who attended Citizens' Advisory Council meetings? The list is impressive: astronaut Buzz Aldrin; George Merrick, head of the North American Rockwell Shuttle program; Fred Haise, then president of Grumman; General Stuart Meyer, formerly commander of the Redstone Arsenal; Stewart Nozette, soon to be named to the National Space Council; space enthusiast Arthur Dula; Lowell Wood; Gordon Woodcock, Boeing engineer and president of the L-5 Society in 1984; former NASA administrator Thomas O. Paine; von Braun rocket team member Konrad Dannenberg; astronauts Gerald Carr, Philip K. Chapman, Gordon Cooper, and Walter Schirra; and Betty Jo ("Bjo") McCarthy Trimble. Trimble headed the letter-writing campaign to keep Gene Roddenberry's Star Trek television series on the air in 1968, and led another letter campaign to name the first Shuttle Orbiter the Enterprise. In addition to Pournelle, Larry Niven, and Harry Stine, a number of science fiction writers with science backgrounds also attended, including Robert Heinlein, Poul Anderson, and Dean Ing.

A key member of the Citizens' Advisory Council involved in the creation of the SDIO SSTO Program was Max Hunter. Hunter, a 1944 graduate of MIT's graduate program in aeronautical engineering, worked in the Douglas Aircraft Company at its Santa Monica, California, plant. There, as an aerodynamicist on a variety of commercial aircraft, the Santa Monica plant's specialty, Hunter began to consider aircraft operating costs. In October 1946, as Douglas entered the missile field, Hunter became head of missile aerodynamics and oversaw the design for the Nike-Ajax, Hercules, and other missiles. Then, as Chief Missiles Design Engineer, Hunter oversaw the design of the Thor, Nike-Zeus, and other missiles, and as Chief Engineer of Space Systems, he was responsible for such Douglas space efforts as the Thor (known commercially as the Delta) and the Saturn S-IV stage.

Max Hunter and the Idea of Low-Cost Space Transport. While serving as head of the Douglas internal Space Committee, Hunter conceived the idea of a nuclear-powered rocket known as RITA, for Reusable Interplanetary Transport Approach. It promised "economy of operation, convenience in terms of flight schedule, ease of maintenance, and versatility of utilization." It would be a reusable, single-stage-to-orbit launcher capable of carrying payloads into orbit, to the Moon, or to other planets. "The real reason for building nuclear space transport vehicles," the RITA report argued, "is their ability to achieve low cost space transportation." Subsequently, Hunter served on the National Space Council under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson before leading the Lockheed Shuttle team. He later turned his attention to the Hubble Telescope and applications of high energy lasers, until his retirement in 1987. In 1985, though, shortly before leaving Lockheed, Hunter decided it was time to start thinking about a replacement for the Space Shuttle, and in August of that year he wrote a short paper, revised in April 1987, following the loss of the Challenger, on the need to replace the Shuttle with a less expensive launch system. The title of that paper, "The Opportunity," referred to a business opportunity, "a classical entrepreneurial opportunity … in space commerce, indeed all of space…" "The key" to exploiting that opportunity was "space transportation." A lower cost Shuttle replacement was needed to open up space commerce. "With what we now know about space transport design," Hunter argued, "such a new vehicle should not cost much more per pound to develop than an experimental airplane and possess airplane-class safety." This new space vehicle would be "a relatively small hydrogen-oxygen rocket" capable of placing "about 20,000 pounds in orbit. It would stand no higher than the tail of a Boeing 747 on the pad. With readily available modern electronics, only a few people would be required for launch and operations." Moreover, he estimated, "if the development cost per pound were even five times as high as a modern airplane, it would still cost only several $100 million (not billions) to develop. The cost of the propellants would be less than $5 per pound of payload placed in orbit."

Here, too, Hunter wrote, was an "opportunity … [for] the development, using aircraft-like techniques, of a new launch vehicle. It would be relatively small (so was the Douglas DC-3), use the most modern of operational techniques, and rely heavily on basic technology developed by the shuttle and other programs. It would likely be a single-stage-to-orbit hydrogen-oxygen rocket. It would have a sufficient number of engines that it could stand an engine failure at any time after launch and either complete its mission or successfully abort. This is the key to both operational and test flying with airplane-like techniques."

While still employed at Lockheed, Hunter worked on the design of such a launcher, called the X-Rocket. He hoped that the Lockheed name might win converts in the federal government, and as a result, interest investors in the X-Rocket. The X-Rocket name was intended to signify that it was part of the long tradition of experimental aircraft indicated by the letter X, such as the X-1 and the X-15. Alternately, Hunter called the Lockheed program the XOP, for Xperimental Operational Program, "to emphasize," in Hunter's words, "that it wasn't so much the new device as the different operation which would produce the improvements."

The X-Rocket/XOP was a gum-drop-shaped reusable single-stage-to-orbit vehicle that took off and landed vertically and could be operated with or without a human onboard, "no big deal either way," in Hunter's words. It featured simplified, airplane-like checkout, launch, and operations, with a minimal launch crew and a short turn-around time. Although the X-Rocket program sought to demonstrate certain technologies, cutting the number of people needed to launch a spaceship was the program's top priority. In the words of one X-Rocket briefing chart: "eliminating the standing army-from day one-is the truly crucial item. It may be the only crucial item."

Between 1985 and 1987, Max Hunter briefed a myriad of military and civilian officials on his proposed X-Rocket, including Vice Admiral Richard H. Truly, NASA Associate Administrator for Spaceflight, and General James Abrahamson, then Strategic Defense Initiative Organization director. Nonetheless, Lockheed discontinued support for the X-Rocket after a negative review by the Lockheed Missile Systems Division. Without the Lockheed name behind it, the SSX appeared to have even less of a chance of finding support. Indeed, the SSX concept would have remained just that, a concept, if it were not for Hunter's attending a meeting of the Citizens' Advisory Council on National Space Policy. The Meeting with Quayle.

Pournelle convened a meeting of the Citizens' Advisory Council during the weekend of December 5, 1988 to decide which type of launch vehicle the Council should champion. The 1988 Presidential election had just been held, and the Bush-Quayle ticket won. Vice President-Elect J. Danforth Quayle soon would be chairing the revived National Space Council. Its specific duties involved coordinating space policy within the various agencies of the Executive Branch. Pournelle and the Council had hopes of influencing the new Vice President and his National Space Council.

The key to translating Max Hunter's SSX into a real government program was another member of the Citizens' Advisory Council, Retired Lt. Gen. Daniel O. Graham. Former deputy director of the Central Intelligence Agency and former director of the Defense Intelligence Agency. He also served as Ronald Reagan's military advisor in both presidential election campaigns. Graham founded Project High Frontier after Ronald Reagan's first election with help from members of the President's kitchen cabinet. In March 1982, the Heritage Foundation published the group's report as High Frontier: A New National Strategy. The book called for a space-based missile defense, namely, the global ballistic missile defense (GBMD) system. Graham, like Max Hunter, argued that a U.S. space-based global defense system would bring about a Pax Americana similar to the Pax Britannica brought by Britain's domination of the world's oceans. However, Graham, drawing on the strategic theories of Alfred T. Mahan (1840-1914), a professor at the Naval War College, also stressed the interconnection between industrial exploitation of space and military command of the new high ground.

As Graham reminisced in his autobiography: "For years we [High Frontier] had sought ways to lower launch costs, because according to solid estimates from DoD of the costs of deploying the spaceborne elements of SDI, a large percentage were launch costs. In the Fall of 1988, I learned of a solution. Maxwell Hunter, a well respected and able aerospace engineer came to my offices."

When Hunter explained his SSX idea to Graham, Graham saw the SSX as having implications for all space needs: "I was highly impressed by Hunter's proposal. Here, at last, was a solution that involved a fundamental improvement in space transportation of revolutionary potential for enhancing military, civil, and especially commercial uses of space." Graham later related: "I was excited about the SSTO idea, but I knew my technological limitations and was not ready to throw this cat into the space community canary cage without hearing from other experts. I suggested to Max that we call together a group of such experts and get their reactions. He agreed, and I contacted Dr. Jerry Pournelle to call together his loose confederation of experts and enthusiasts, the Citizens Advisory Council on National Space Policy, to critique Max's proposal."

Although we do not know what Hunter proposed to the Citizens' Advisory Council, nonetheless, a clue is in Hunter's paper, "The SSX Single Stage Experimental Rocket," written March 15, 1988, in which he laid out the same ideas briefed to the Council later that year. The paper argued that the technologies (novel lightweight materials (alloys and composite materials) for fabrication of the aeroshell and fuel tanks) were now at hand to build a single-stage-to-orbit vehicle. The vehicle would abort like an airplane, not a missile Hunter wanted rockets to be operated more like aircraft: airplane autonomous operations, minimal launch crew, and short turnaround time.

Hunter's SSX presentation won over the attending members of the Citizens' Advisory Council, who then took a position in favor of Hunter's single-stage-to-orbit design. Danny Graham made Hunter's SSX the subject of a personal crusade. Graham later recalled: "I expended my political blue chips with Dan Quayle to get an appointment to sell him the SSTO idea." Now, Hunter's SSX had not only the backing of the Citizens' Advisory Council (an unclear advantage in and of itself, given Hunter's failure with the Lockheed name behind his efforts), but the support of Graham and his High Frontier national organization. Moreover, as Graham pledged at the meeting, he would unlock the door to the White House.

The goal of the meeting with Quayle was "to try and get some form of Administrative support for the pursuit of the SSX concept." The SDIO was the logical choice for the SSX's institutional home. Then the day came to meet Vice President Quayle. The date was February 15, 1989. The three who briefed Quayle were Max Hunter, Danny Graham, and Jerry Pournelle. At the time of the briefing, Quayle had been Vice President for less than a month. The SSX program schedule, as pitched to the new Vice President, was filled with political stratagems geared toward the 1992 presidential elections. The timing of the public announcement could be made "at about the time of the State of the Union Address in 1991," Pournelle wrote the Vice President, "and will be followed by a number of safely predictable newsworthy achievements in 1991 and 1992. SSX can also perform a suitably significant mission to mark the 500th anniversary of Columbus' discovery of the New World on October 12, 1992."

As Pournelle left Quayle's office after the February 1989 briefing, he recalled Quayle asking "if this really could be done before 1992." His answer, written in a subsequent letter, was: "Yes. We can do something both significant and spectacular in space before 1992." The specific program schedule presented to Quayle, according to Pournelle, called for the critical design review and final funding commitment to take place in December 1990; the public project announcement in January 1991; first flight test in spring 1992; and orbital flight on Columbus Day, 1992.

Quayle was key to any change in space policy, not just as the key Bush Administration figure on space policy, but as the head of the newly reformed National Space Council. Did Quayle understand the importance of the SSX proposal? Graham observed that: "It appeared that Mr. Quayle, although a very "quick read," i.e., able to grasp ideas quickly, was not much interested in the details of SSTO technology." How momentous was this meeting in Quayle's mind? In the published autobiographical memoirs of his vice presidential years, Quayle devoted a respectable number of pages to space issues, chiefly the Space Exploration Initiative (a mission to return to the Moon and to land an astronaut on Mars), space station, and conflict with NASA, which Quayle characterized as "a very pampered bunch." However, he failed to mention the SSTO Program entirely. The Cold War as a Driver of Reusability.

In selling the proposal, the SSX was tied to the SDI project known as Brilliant Pebbles, an SDI configuration that consisted of a large number of lightweight, low-cost, single hit-to-kill kinetic kill vehicles that provided integrated sensors, guidance, control, and battle management. Basically, Brilliant Pebbles was intended to be an autonomous space-based defensive interceptor. Each Pebble would have its own sensors, computers, and thrusters to detect, track, and intercept enemy missiles. Brilliant Pebbles also meant that the SDIO no longer had a need to place 100,000-pound (45,000 kg) laser battle stations in orbit. Rather, because each Brilliant Pebble weighed about 100 pounds (45 kg), SDI launch needs shifted to a lighter, medium-lift rocket, such as that proposed in the SSX program.

In order to set up Brilliant Pebbles, an unprecedented number of launches would have to take place. Because the SSX promised low-cost access to space, it was again well suited to the Brilliant Pebbles concept. In general, in order for a reusable launcher to be cost-effective, it has to fly many times. Each flight has to amortize the vehicle's massive up-front capital expenses, such as research and development and manufacturing costs. As Steve Hoeser explained: "It's almost equivalent to buying a 747 or a C-5A for many hundreds of million dollars and using it five times a year. It is hellaciously expensive. Each flight gets to be very, very expensive." Brilliant Pebbles, then, with its need to launch hundreds of times, was well suited for a reusable launcher. Furthermore, there certainly were not yet enough NASA or commercial payloads to justify financially the SSX.

The Vice President passed the proposal to the National space Policy. Both the Aerospace Corporation and NASA Langley's Vehicle Analysis Branch studied and approved it. A year after the meeting with Quayle, in March 1990, the SDIO announced a Request for Proposals for Phase I of the SSTO Program in Commerce Business Daily. Phase I would consist of "research into single stage to orbit [vehicles]." Specifically, that "research" would "consist of design trades, identification of the critical path technology, and a risk reduction demonstration along that critical path." SDIO expected to make not one, but "Multiple contract awards of up to four contracts." Phase I would last only ten months. SDIO then would hold a competition for Phase II, the manufacture and flight testing of a suborbital vehicle. The SDIO would select "the most promising concept(s)" for Phase II, the idea being to select one or two contractor concepts for Phase II. Phase III would consist of the design, development, construction, and flight of a full-scale orbital prototype.

The Statement of Work made it clear that the SSTO Program was not about developing new technologies, but rather operations. The long-range program goal was an operational manned reusable single-stage-to-orbit vehicle "with aircraft style operations." From beginning to end, as Max Hunter and others had advocated all along, the emphasis was on operations, in order to achieve what were called "aircraft-like operations": the vehicle had to be reusable, had to require a small operating crew, and could be turned around quickly. A classified appendix to the RFP provided technical information on a classified payload that the vehicle would launch into orbit. The payload was a description of Brilliant Pebbles. This was the idea of Gary Payton, the SDIO official who co-authored the Statement of Work.

Following the design studies of Phase I, SDIO awarded the Phase II vehicle construction contract to McDonnell Douglas. For the most part, the 13-page Phase II Statement of Work defined the vehicle in terms of operational performance, not technology. In the words of the Statement of Work, "By balancing design, operational and maintenance factors, the SSTO will drive system costs to their lowest possible level." In order to achieve low-cost operation, the vehicle had to require minimal maintenance between flights, and had to allow rapid turnaround, that is, the time required to service the vehicle, reload, and prepare it for launch, "by today's standards." The Statement of Work stipulated that: "The vehicle must be capable of being turned around … within 7 days of landing with the expenditure of no more than 350 man-days." However, it was the Phase II vehicle that had to meet these turnaround times; the Phase III vehicle could require more than 350 man-days. The amount of time a mission had to spend between initial request and launch should be less than 30 days. The vehicle also had to have "launch rate surge capability" (doubling the routine launch rate) "for a minimum of 30 days."

Between the Phase I and Phase II Statements of Work, a significant change had taken place. While Phase I tied the program to Brilliant Pebbles, the Phase II Statement of Work declared that the operational vehicle should be able to "perform Space Transportation System (STS)-like (Space Shuttle-like) operations for rendezvous, docking, and also propellant refueling to either active (cooperative) or passive (noncooperative) spacecraft." Those capabilities were required in order to carry out missions not associated with Brilliant Pebbles. With the Phase II Statement of Work, the SSTO Program clearly was disengaging itself from Brilliant Pebbles and the SDI's Cold War programs and was seeking a niche outside missile defense. Possible missions for the future operational vehicle now included deployment of satellites and other payloads in low and geosynchronous orbit, Space Station and Space Shuttle support, and satellite recovery, replacement, and improvement. In addition, the Statement of Work asked contractors to consider how their vehicle might be used to support the Space Exploration Initiative (SEI), the Bush Administration space enterprise to return to the Moon and to land astronauts on Mars.

A New World Order.

Between June 1990 (Phase I Statement of Work) and June 1991 (Phase II Statement of Work), the world had undergone considerable changes that directly impacted the country's launch needs. Indeed, those changes already had started to occur even before the meeting with Dan Quayle.

On December 8, 1988, Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev started the chain of events in an address delivered before the United Nations General Assembly. Gorbachev announced drastic cuts in the Soviet military presence in Eastern Europe and along the Chinese border, including a withdrawal of six tank divisions from East Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary, and the entire disbanding of Soviet forces in those countries by 1991. Later that month, Gorbachev met with President Reagan and Vice President George Bush, and discussed ending the Cold War.

In March 1989, Hungarian Prime Minister Nemeth visited Moscow to tell Gorbachev personally that the Hungarian leaders were planning free multiparty elections. The month before, the Hungarian government removed the barbed wire on its border with Austria and the West. The Soviet Union did nothing. In Poland, where a wave of political strikes led by the opposition Solidarity movement paralyzed the country, the Communist government opened talks with Solidarity, then in June 1989, the country held multiparty elections. The Communists lost; Solidarity won 99 out of 100 seats in the Senate. Within weeks the first non-communist prime minister in the Soviet bloc took office. With these first fractures, the Iron Curtain began to disintegrate. Then in November 1989, the Berlin Wall came down. Czechoslovakia and Romania cast out their Communist governments, as well. Boris Yeltsin, former Communist Party chief in Moscow, a popular and ambitious politician, used the economic discontent spreading through the Soviet Union to weaken Gorbachev politically, and in May 1990, he became parliamentary leader of the Russian Republic. Yeltsin was on the road to power.

To use the terminology of President George Bush, a new world order was emerging. The whole nature of antiballistic missile defense needed to be reconsidered. In late 1989, President Bush ordered a review of the SDI program as part of a broader reconsideration of U.S. strategic requirements for the New World Order that Bush thought was emerging. The review was completed in March 1990 by Henry F. Cooper, who since 1987 had served as America's chief negotiator at the Defense and Space Talks in Geneva. When Cooper became the third director of the SDI Organization on July 10, 1990, he worked to implement his own recommendations.

Brilliant Pebbles was replaced by GPALS (Global Protection Against Limited Strikes). The new missile defense architecture cut the estimated need for spacecraft interceptors by three fourths to only 1,000. At this point, SDIO SSTO program manager Pat Ladner told a reporter: "GPALS and SSTO are not tied together whatsoever," stated Ladner. The break between the SSTO Program and SDIO missions was unmistakable. However, if not Brilliant Pebbles or GPALS, what, then, would be the mission of the SSTO Program vehicle? Was there a mission for the vehicle following the end of the Cold War?

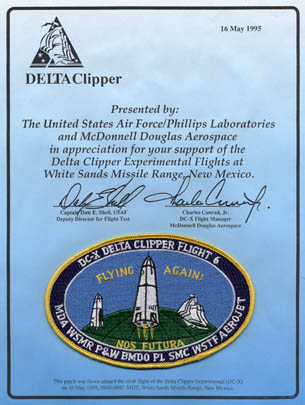

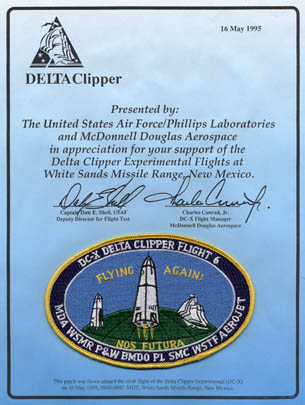

The was the idea behind the Phase II Statement of Work. The SSTO Program could serve all launch needs, whether for SDIO, NASA, or commercial purposes. McDonnell Douglas was looking toward the commercial market, at least in naming the Phase II vehicle. The DC-X stood for Delta Clipper Experimental. The Delta was McDonnell Douglas' ELV, while "Clipper" attempted to evoke the Yankee Clippers. The choice echoed Reagan's 1984 State of the Union Message, when he declared that: "Just as the Oceans opened up a new world for Clipper Ships and Yankee Traders, space holds enormous potential for commerce today. The market for space transportation could surpass our ability to develop it."

How successfully did the SSTO Program survive the end of the Cold War? To what extent did the commercialization of space serve to rescue the program? Unfortunately for the SSTO Program, the end of the Cold War was not the only political change it had to deal with. The November 1992 elections changed the political party of those residing in the White House. President Bill Clinton and Vice President Al Gore soon eliminated the National Space Council, a key source of SSTO Program support. Clinton and Gore also would want to shape military and space policy to suit their own agendas, which were certainly different from those of their predecessors. The new White House soon left its imprint on the SDIO. On May 13, 1993, Secretary of Defense Les Aspin announced that he was changing the name of the SDIO to the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization (BMDO).The SSTO Program quickly followed, changing its name to the Single Stage Rocket Technology (SSRT) Program. These name changes represented more than just pouring old wine into new bottles. The very existence of the SSRT Program was at stake, as Congress and the Pentagon seemed bent on deleting it from the budget. However, although those institutions had the power to support or destroy the program, only a few staff members and even fewer Representatives and Senators in Congress and the Department of Defense really knew the SSRT Program existed, and the number of the program's "enemies" was equally small. Funding the SSRT Program was always a case of a small number of people trying to make these two powerful institutions comply with their wishes, the continued funding of the program.

Congressional and Bureaucratic Problems.

This budgetary assault continued throughout 1992, 1993, and 1994, when the SSRT Program came to a definitive end. A critical consequence of those budget cuts was open hostility among supporters of various launch systems. Indeed, the hostility was voiced not just on the floor of the House and Senate, but in the press as well, in the form of invectives, denunciations, and ad hominem attacks. While the Titan IV expendable launcher and the Centaur upper stage rocket came under Congressional scrutiny of their own, hostility toward the SSRT Program came from the champions of the National AeroSpace Plane and the Advanced Launch System (renamed the National Launch System, then Spacelifter new generation of expendable launchers capable of lifting heavy payloads funded jointly by the SDIO (now BMDO), NASA, and the Department of Defense. Support for NASP waned over the course of 1992. NASA Administrator Daniel Goldin limited his agency's annual program contribution to $75 million, while the Pentagon set its NASP funding level at no more than twice that of NASA. That left the Advanced Launch System (ALS) as the primary source of program-based hostility toward the SSRT Program.

The SSTO/SSRT Program had support in Congress. In New Mexico, where the DC-X flight tests took place, Senator Pete V. Domenici, a Republican and member of the powerful Appropriations Committee, saw in the program the potential development of a spaceport in New Mexico and with it jobs. Strong political support in the House came from Representative Dana Rohrabacher, a Republican member of the House Science, Space, and Technology Committee.

The precarious nature of SSTO/SSRT Phase II and Phase III funding was demonstrated as early as September 1991, when the fiscal 1992 Department of Defense authorization bill came under scrutiny by Congress. To make a long and complicated story short, a Pentagon official used a bureaucratic maneuver known as a Format I to transfer $27 million from the SSTO Program to an expendable launcher program, the National Launch System. The Format I was rescinded on March 29, 1992, and in April 1992, the DC-X funds were released to the SDIO.

Later in 1992, the program was transferred from the SDIO to ARPA. The SDIO, as we saw, had no mission for the SSTO vehicle. Neither did ARPA, but it was a research and development organization, at least. Although SDIO Director Henry Cooper supported Phase II (the DC-X), under funding pressure from Congress, as well as interagency pressure growing out of the perception that the SSTO Program had become a popular rival to other launch system programs, Cooper chose not to pursue the SSTO beyond testing of the DC-X.

The DC-X Becomes a NASA Program.

In 1993, McDonnell Douglas rolled out the DC-X, and the test flights began that summer. Test flights were suspended as funding again was lost in the quagmire of Congressional and bureaucratic budget fighting. Furthermore, following the Moorman Report of 1993, White House space policy determined that the Pentagon would develop ELVs, and that NASA would develop reusable launchers, like the DC-X. Again, abbreviating a rather complicated chain of events, NASA saved the DC-X test flights with a payment of $1 million. Later, NASA and the Department of Defense signed an agreement that transferred the vehicle to NASA, where its budgetary future would be determined more by the space agency than by Congressional budget fights.

NASA turned the DC-X from a demonstrator of operational concepts into a technology demonstrator, the DC-XA, known also as the Clipper Graham in honor of the late Danny Graham who, more than anyone else, had made the program possible. At NASA, the DC-XA became a part of a new program, the Reusable Launch Vehicle Program. It joined an existing small booster program, renamed the X-34, and the Advanced Technology Demonstrator project, soon to be known as the X-33 program.

Conclusion.

We now come back to the original question: What drives reusability? Reusability has a powerful economic and emotional attraction. It offers enormous operational cost advantages. Also, to be frank, the idea of taking off and landing a single-stage-to-orbit reusable rocket like Buck Rogers is "cool." The major disadvantage of reusability (especially single-stage-to-orbit reusability) is technological. New technologies (new engines, new thermal protection systems, new aeroshell and component materials) need to be researched, developed, tested, and evaluated in order to achieve a reusable launcher. These RDT&E costs are higher for RLVs than for ELVs, mainly because (thanks to the Cold War) we have extensive expendable experience.

The NASA launcher symposium proposed three major drivers behind launcher development. The first, the Cold War, was clearly behind the conception of the SSTO Program and its conceptual predecessor, the SSX. The second driver, NASA use, definitely enabled the DC-X to complete its SDIO/BMDO flight test series, and made it part of a civilian technology development program, NASA's RLV Program. The third driver, space commercialization, certainly was a hoped for driver of the SSTO Program, even as the program prepared to enter Phase II. Both the Statement of Work and the McDonnell Douglas name for the vehicle belied an effort to attach the program to the commercial space sector. That did not happen.

After the end of the SSTO/SSRT Program, McDonnell Douglas continued to attempt to sell the "DC-X" concept, but to government customers. The concept vied for contract dollars in the military's spaceplane program, which was canceled, and the company proposed an evolved version of the DC-X as its Phase I concept for the X-33 program. However, NASA did not pick the McDonnell Douglas for Phase II of the X-33 program.

Despite these failed efforts to sell an evolving DC-X to government customers, the McDonnell Douglas people who worked on the DC-X did find a future in private enterprise, especially after Boeing digested McDonnell Douglas. The new home of most of the DC-X team was not at Boeing, but at Universal Space Lines and its associated companies founded by the former head of DC-X flight operations, Pete Conrad.

The story of the DC-X, then, shows the role of both the Cold War and NASA as drivers in the development of reusable launchers, but does not evidence a role for space commercialization, despite the intentions of the vehicle's builders, McDonnell Douglas, or SDIO program officers.

Something else former-President Clinton and former-VP Gore cost us.

DC-X ping.

From my posting - The Path Not Taken - http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/1849387/posts

...The X-33 itself wasn’t designed to go into orbit; it was a subscale version intended to show that a larger orbital vehicle (called “VentureStar” by the winning contractor, Lockheed Martin) could be built commercially. Because it incorporated several cutting-edge technologies in a single vehicle, it was a very risky program, and in fact was chosen for that reason—NASA wanted to “push the technological envelope.”

... Lockheed Martin achieved its strategic business objective simply by winning the contract. If the X-33 project was a success, Lockheed would take away business from its competitors. And if it was a failure, Lockheed would prevent the development of a new vehicle to compete against its own existing Atlas and Titan rockets and its stake in the space shuttle. NASA apparently didn’t notice—or didn’t care—that by selecting an incumbent launch vehicle provider, there were intrinsic incentives for program failure. Nor did it occur to them, more generally, that one shouldn’t seek innovation from an entity with a massive stake in the status quo. In the end, the X-33 never flew and the project was cancelled in early 2001 after spending more than a billion dollars.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.