Posted on 01/16/2006 10:29:44 AM PST by Paul Ross

First-Flight Shuttle Ride

Aviation Week & Space Technology

01/16/06

author: Col. R. Mike Mullane

Jan. 28 marks the 20th anniversary of the 1986 Challenger space shuttle accident that killed NASA astronauts Dick Scobee, Mike Smith, Judy Resnik, Ron McNair, Ellison Onizuka, Hughes corporate payload specialist Greg Jarvis and teacher-in-space Christa McAuliffe.

Nearly 18 months before the Challenger accident, the Thiokol solid-rocket boosters used on Discovery's Mission 41D experienced the first major "blow-by" of gases around O-ring seals--the same problem that later doomed Challenger. Former astronaut USAF Col. (ret.) Mike Mullane, a mission specialist on that Discovery flight, describes his experience from the perspective of post-Challenger hindsight in this exclusive excerpt from his forthcoming book, Riding Rockets: The Outrageous Tales of a Space Shuttle Astronaut.

Postflight analyses of the Mission 41D O-ring blow-by incident contributed to an ongoing Thiokol/NASA investigation into O-ring-related problems. But that investigation failed to identify how serious the blow-by issue was prior to the loss of Challenger and her crew. The same O-ring malfunction reoccurred on Mission 51C, then led to the subsequent Challenger tragedy.

Mullane rode on Discovery's top deck with mission commander Henry (Hank) Hartsfield, copilot Mike Coats and flight engineer Steve Hawley. McDonnell Douglas payload specialist Charles Walker and astronaut Judy Resnik, who later died during Challenger's fatal mission, were seated on the middeck.

Mullane subsequently flew two other space shuttle missions--one in 1988 and another in 1990, both on Atlantis. The following excerpt begins at liftoff of Discovery's first flight on Aug. 30, 1984. After both the Challenger and Columbia accidents, Discovery returned the shuttle program to flight.

At the count of "zero," there was no doubt we were about to slip "the surly bonds of Earth." The hold-down bolts blew, we were slapped with a combined thrust of more than 7 million lb. and a new wave of intense vibrations roared over us.

"Houston, Discovery is in the roll," Hank reported.

"Roger roll, Discovery."

The shuttle's autopilot was now in control. Hank and Mike flipped their attitude director indicator (ADI) switches to change the mode of that "eight ball." I watched Hank's ADI reflect Discovery's tilt toward the just-risen sun.

If our ascent were nominal, the ADI switch would be the only one touched until MECO [main engine cutoff] some 8 min., 4 million lb. of propellant and 17,300 mph. away. Please, God, that it be so, I thought. Having to use other switches could only mean something wasn't nominal.

My eyes fell to the contingency abort cue card Velcroed to Hank's window frame. The card detailed procedures for ditching the shuttle--which all of us knew would spell death. NASA called all the other abort modes "Intact Aborts," indicating the orbiter and crew would be recovered "intact" in the U.S., Europe or Africa. But the agency couldn't bring itself to call a ditching abort a "Not-Intact Abort." Like sailors of old, who painted their ship decks red so the blood of battle wouldn't shock a crew, NASA camouflaged ditching procedures with the title, "Contingency Abort." One of the card's more helpful suggestions was to ditch parallel to the waves.

Astronauts joke that contingency-abort procedures are just something to read while dying, a jest that had seemed funnier at the office coffee bar than it did now.

Except for the noise, vibrations and g-forces, the ride was just like the simulator. Yes, that's akin to the circus Human Cannon Ball saying, "Except for the earsplitting explosion, the g-forces and the wind up your nose, it's just like sitting on a case of unlit dynamite."

"Throttle down," Mike, our pilot, said. We were 40 sec. into flight, and vibrations intensified as our vehicle punched through the Mach-1 "sound barrier." Everything created shock waves--the giant, bulbous external tank; the pointed cones of two SRBs [solid-rocket boosters]; the orbiter's nose, wings and tail, and the struts holding it all together. Interplaying shock waves created an aerodynamic cacophony, as engines were throttled back to keep the vehicle from tearing itself apart.

Our seats wiggled and groaned under the stress. I was amazed by the shuttle's flexibility and reminded of my childhood, when I would slide down a bumpy, snow-filled arroyo in a cardboard box. Now, as then, I wondered how my cockpit could remain intact through all the shaking.

"Throttle up." The air was thinning and aerodynamic pressures decreasing. The three Rocketdyne beauties at our backs were once again spooling up to full power.

What a rush it was to feel the buildup of thrust--like jamming the throttles of a fighter into afterburner. I suspect every pilot itched to snatch the controls and manually shove the space shuttle main engine throttles to full power. How often would you have your fingers wrapped around 1.5 million lb. of thrust control?

Prayers from everyone in the cockpit were identical--that God would continue to smile upon those space shuttle main engines (SSMEs). We most feared these, and for good cause. There had been myriad SSME ground test explosions and premature shutdowns.

We were also strapped to two SRBs, each burning nearly five tons of propellant per second, but nobody gave them a passing thought. No engineer had ever come to a Monday morning meeting to explain away an SRB ground-test failure. The SRBs had always worked.

But even as we scorched the prayer line with our pleas for flawless SSME function, both SRBs were betraying us. A primary O-ring at several joints in each SRB tube had failed to seal as the motors ignited, allowing tentacles of flame to wiggle between SRB segment facings. Like something alive and trapped, the hot gases had started to eat at the O-rings' rubber. A leak on the left-side SRB was bad enough to let hot gas past the primary O-ring.

Though we wouldn't know it until after the Challenger disaster, we had just experienced the first case of what Thiokol engineers would later call "blow-by." Hot gas had penetrated the space between primary and backup O-rings. Had a leak persisted, both O-rings would have been consumed, history would have recorded a Discovery disaster instead of Challenger, and our "Zoo Crew's" names would have been etched on an Arlington National Cemetery monument. But the leak hadn't persisted. Inexplicably, the primary O-rings had resealed.

The clock was approaching T+2 min. and the invisible hand of 2.5g pushed me deeper into my seat. I reached forward, drew my hand back, then reached forward again. Veterans had warned it was tough to maneuver an arm under launch and ascent g-loads, and it was a good idea to practice in case an emergency required reaching a switch.

"You see that?" Hank's question reminded me of Judy's prior warning: Don't end any sentence with the word "that." Needless to say, my ears perked up.

Mike replied, "Yeah, it looks like foam from the tank is flaking off."

The pilots discussed particles racing past our windows, sometimes striking the transparencies. Their voices reflected no concern, so I quickly dismissed the comments. The ET [external tank] foam insulation was light; I couldn't imagine it damaging an orbiter. Nineteen years later, a briefcase-size chunk of foam would rip from that tank, dooming shuttle Columbia.

"PC less than 50," Hank noted. A computer message indicated SRB chamber pressure had fallen to less than 50 psi. Then a loud metallic bang shook the cockpit, and a flash of fire whipped the windows as both boosters separated from the ET and started tumbling. They would soon parachute into the ocean.

The sudden loss of 6 million lb. of thrust, accompanied by dead silence, caught me by surprise. Had all three SSMEs also shut down? I leaned to my left, staring at the engine status lights, checking for their deadly red glow. But the lights were off, the radios quiet. I swallowed my heart back into place.

Maybe I had slept through the training session that described SRB separation and the quiet, velvet smoothness that followed. There was nothing wrong with Discovery. With most of the atmosphere behind her, there was no air to rattle us with shock waves, and the SSMEs were as finely tuned as a Rolex. Nearly 1.5 million lb. of thrust still were blasting 100 ft. behind our backs, but nary a whisper of noise or ripple of vibration reached us. The ride became as smooth as a politician's lie.

Hank's altitude and velocity tapes scrolled upward as the sky faded to abysmal black. Sunlight streamed through the windows, yet the sky was utterly dark. It was my first space experience, something I could never view as an earthling: simultaneous night and day; simultaneous high-noon and deep midnight.

"Discovery, you're two-engine TAL." We now had enough altitude and speed to cross the Atlantic and land in Senegal, Africa, if one engine failed, a maneuver known as a Trans-Atlantic Landing abort. NASA had prepositioned an astronaut at the Dakar international airport to assist air traffic control personnel, if we aborted. He also had our passports and visas. I briefly envisioned us standing in a customs line, still in our shuttle flight suits, our helmets tucked in the crook of one arm, while a fez-sported bureaucrat asked, "Anything to declare?"

"Discovery, you're negative return." The Return-To-Launch-Site (RTLS) abort window had closed. We were now too far from Florida and headed east too fast to land back at KSC [Kennedy Space Center]. If an engine failed, we were committed to a "straight ahead" abort. That was OK; nobody wanted to do a turnaround RTLS abort, an unnatural act of physics. If selected, it required pitching the shuttle into an outside loop that would point us toward Florida. Because it would take a few minutes to cancel our eastward velocity, we would actually be flying backward over the Atlantic. Ultimately, we would emulate a million-lb. helicopter, 50 mi. high, with zero forward speed, before starting a slow acceleration toward our objective 200 mi. away. The experts swore the procedure would work, and Mike and Hank had practiced thousands of simulated RTLS aborts, but nobody wanted to conduct the first field test.

We continued a nominal ascent through 30-mi. altitude. It occurred to me that I could die without ever having seen Earth from space. The shuttle's nose was so high, and I was sitting so far aft in the cockpit, that I couldn't see our planet. But a window above and slightly behind me offered an Earth view, because the shuttle flies to orbit upside down.

I glanced furtively at Steve Hawley, who sat in the center-seat flight engineer position. His head was making small jerking motions, his eyes scanning every display. There wasn't an electron in Discovery's body that Hawley's brain wasn't processing.

With him at my side, I wouldn't be missed for a moment of sight-seeing. Under mounting g-forces, I craned my neck up and back, until I thought it would break, but the contortion worked. I could see the Earth receding below us. Scattered cumulus clouds had been reduced to points of white, and varying sea depth was marked by different shades of blue. It wasn't much of a view, and I was condemning myself to one hell of a neck ache to capture it, but it was enough.

We were approaching 50-mi. altitude, the magic line that would make us official astronauts. I had always thought this artificial altitude requirement was bean-counter trivia. In essence, it implied that riding a rocket didn't really get dangerous until you hit 50 mi. In reality, if your shuttle didn't make it to 50 mi., the machine had killed you. Later, Mike Smith--a rookie killed on Challenger--didn't die as an astronaut, according to officialdom. He only reached a 10-mi. altitude. (Note to NASA: When the launch pad hold-down bolts blow, you've earned your gold.)

Hank started a countdown. "Here it comes . . . 48, 49, 50 mi. Congratulations, rookies. You're officially astronauts."

We all cheered, Judy, Steve, Mike, Charlie and me relishing the moment. I experienced a momentary calm not unlike what I suspect someone summiting Mt. Everest might.

A few thousand things still could kill me, but their threat couldn't diminish the moment. I stared into the black, while images of childhood played in my mind--my homemade rockets streaking upward from the Albuquerque deserts, my dad, on his crutches, cheering; my mom helping me bake fuels in her oven, cleaning coffee cans for my "capsules"; [me] lying in the desert, watching Sputnik and Echo streak across the twilight sky. I had achieved a dream of 10,000 nights. I was an astronaut.

My distraction lasted a few heartbeats, yet it seemed an age since our cheers had ceased. I looked at Steve again. He was still mind-melding with Discovery, sucking in every bit and byte. I got back on the instruments, listening for Mission Control's other abort-boundary calls.

"Discovery, you're single engine TAL."

"Discovery, you're two-engine ATO [abort to orbit]."

"Discovery, you're press to MECO." This was the sweetest transmission of all. It meant we could still make it to orbit, even if one SSME failed. As an astronaut once joked, "Surely God couldn't be so mad at us that He would fail two engines."

At about 8 min., the main engines throttled back to maintain a 3g acceleration to prevent Discovery from rupturing. With a nearly empty gas tank, our engines now had the muscle to overstress the machine. A reduction in power prevented that.

Hank's velocity tape still raced upward, showing 20,000 ft./sec., then 21,000 . . . 22,000 . . .

Every 15 sec., Discovery was adding another 1,000 mph. to our speed. We were giddy with excitement, but our laughs were distorted by g-loads.

"Houston, MECO. Right on the money." Hank's call elicited another cheer. Discovery had given us a perfect ride.

Retired astronaut Mike Mullane is a veteran of three space shuttle missions. His recently published life story, Riding Rockets: The Outrageous Tales of a Space Shuttle Astronaut (Copyright 2006 by Mike Mullane.

Printed by permission of Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster Inc., New York), provides an insider's perspective on the shuttle Challenger tragedy and the astronaut culture. He lectures throughout corporate U.S. about teamwork and leadership (www.MikeMullane.com).

"For those who fly....or long to."

Contrails is an Aviation Week & Space Technology initiative to capture the untold stories that collectively make up the rich lore of aviation and space.

Further stories from the Shuttle Discovery...

/johnny

But it is unlikely he will ever get victory over the truism...No Bucks, No Buck Rogers!

I had the pleasure of meeting Jack Swigert*, pilot of Apollo 13, and I've actually spoken with Mike Coats, who is mentioned in this piece. Whenever I'm around these guys and these kinds of flyin' machines, I'm a little kid again, listening to the Mercury countdown or reading with horror about the Apollo 1 disaster.

It's nice there are still heros.

*Swigert, who was running for congress from Colorado, gave a lecture in Montrose, where I was editor of the newpaper. I covered the event, then sat down with him for a couple of hours afterward and just let him ramble. It was utterly fascinating. He finally asked if I would give him a lift back to his hotel. Being a struggling journalist, my car wasn't exactly in the luxury class. When Swigert, who had survived Apollo 13, saw it, he looked at me and said "Maybe I'd be safer walking."

Oh, by the way, the car was a Mercury.

And these stories really are only the barest of glimpse into the risks. I would still go up in them, but can't wait for the CEV development to solve the safety risks.

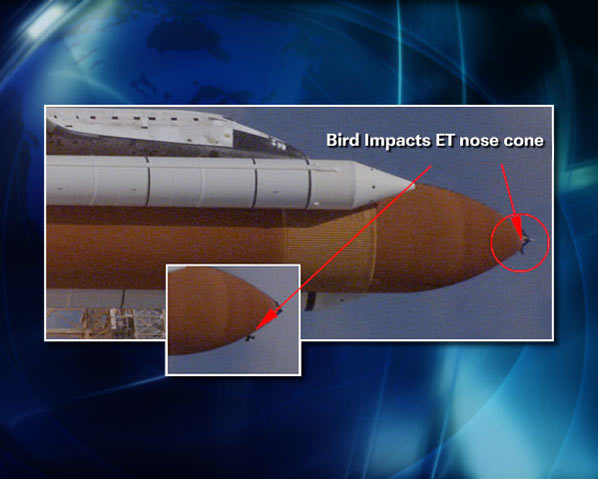

Some recent pictures with debris issues pointed out:

The top of the external fuel tank strikes a bird at liftoff.

Covers are shed from the shuttle thrusters at launch as designed. They are meant to keep water out of the thrusters on the launch pad.

A piece of tile chips off Discovery for unknown reasons.

And scariest of all:

An unknown piece of debris is shed from the external tank just after solid rocket booster separation.

What a ride. Sure wish I could tag along.

Great read! Thanks for the ping.

Great pictures, Paul.

Thanks, and you're welcome.

Ping!

Thanks! Great post, great pics too. (if you have a ping list can you add me? Thx)

Thanks for the ping....

I love this stuff!

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.