Here we go again. Yes, and the law said they COULD NOT be free of the King. Did they follow the law?

Here is the testimony of Dr. Edward J. Erler Professor of Political Science, California State University, San Bernardino and Senior Fellow, The Claremont Institute for the Study of Statesmanship and Political Philosophy, testifying Before the Subcommittee on Immigration and Claims, June 25, 1997. He says that the founders EXPLICITLY rejected the English Common law as the basis for American Citizenship.

To assume that the people in the States who read the Constitution, and elected Delegates to ratify it, somehow understood that the entire definition of citizenship they had always known was being tossed in favor of the unmentioned (in the Constitution) interpretation of some Swiss legal theorist, is preposterous. There is absolutely no basis for inferring that the Citizens of the new United States understood that the basic English concept of birth citizenship had been changed in that document because it was not mentioned.

There is plenty of basis for it, all of which is apparently unfamiliar to you. Vattel was ubiquitous in the United States during this time frame, and particularly well studied by the members of Congress from just prior to the Declaration of Independence until the Final ratification. Indeed, he is mentioned specifically by Several States in their ratification debates, and several more by his work entitled "Law of Nations."

DEBATES IN THE LEGISLATURE AND IN CONVENTION OF THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA, ON THE ADOPTION OF THE FEDERAL CONSTITUTION.

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. IN THE LEGISLATURE, WEDNESDAY, January 16, 1788. Gen. CHARLES COTESWORTH PINCKNEY

...If treaties entered into by Congress are not to be held in the same sacred light in America, what foreign nation will have any confidence in us? Shall we not be stigmatized as a faithless, unworthy people, if each member of the Union may, with impunity, violate the engagements entered into by the federal government? Who will confide in us? Who will treat with us if our practice should be conformable to this doctrine? Have we not been deceiving all nations, by holding forth to the world, in the 9th Article of the old Confederation, that Congress may make treaties, if we, at the same time, entertain this improper tenet, that each state may violate them? I contend that the article in the new Constitution, which says that treaties shall be paramount to the laws of the land, is only declaratory of what treaties were, in fact, under the old compact. They were as much the law of the land under that Confederation, as they are under this Constitution; and we shall be unworthy to be ranked among civilized nations if we do not consider treaties in this view. Vattel, one of the best writers on the law of nations, says, "There would be no more security, no longer any commerce between mankind, did they not believe themselves obliged to preserve their faith, and to keep their word. Nations, and their conductors, ought, then, to keep their promises and their treaties inviolable.

.

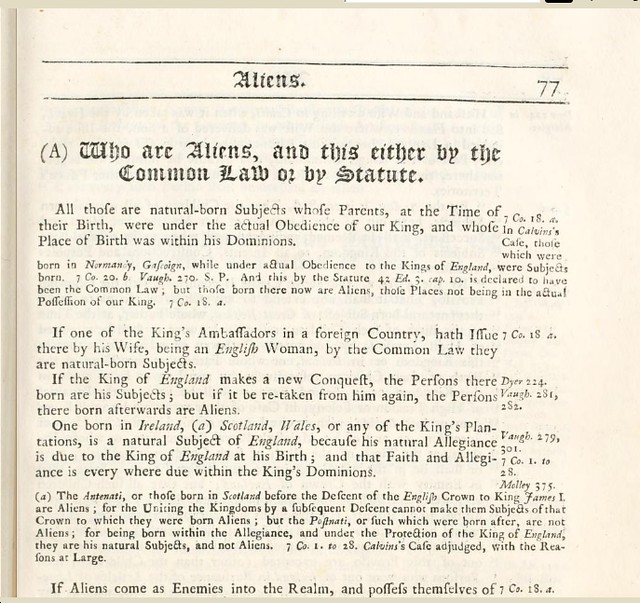

John Adams, (you may have heard of him) LIVED with Vattel's PUBLISHER (Charles Dumas) for several YEARS! Do you think they might have discussed his ideas? Hmmmm??? What's more, The "English Law" version of Subjectship is not as idiotic as many of you would have us believe is the standard for American Law. As demonstrated In John Adams' own Law Book on English Law it says this.

"Whose parents at the time of their birth were under the actual obedience of our King... "

Sounds exactly like the Vattel Version to me.

What some elites may have written in their own debates is irrelevant. What matters is the meaning of the words as commonly understood at the time by the citizens who approved the Constitution, because it is only from them that the validity of the Constitution flows. And any claim that de Vattel's citizenship theory was the one commonly understood by the average American at the time of ratification is simply preposterous.

Well for a rebuttal by an uncommon American, I give you PUBLIUS, otherwise known as James Madison. (1811)

I would suggest you study the issue more thoroughly before opining on the subject. It is always a good policy to UNDERSTAND the opposition arguments before you attempt to refute them. By the way, I've got more evidence. A LOT more.