Does (for example) British Common law "extend past" children of the subject? From what I've read, it seems to indicate "children" and not any further. But there could be British case law that would address subsequent generations. If that were the case, and controlling, then perhaps a large portion of our country would still be considered British Subjects and/or citizens of other countries due to their American revolutionary and before ancestors having come from another land. Following that, only "Native American Indians" might be considered as NBC. I would say the concept's in Law of Nations supersedes that of British common law, on this issue, as it's been "on the books" far longer that the latter. Somebody else said that about the Law of Nations--that just isn't so. The Law of Nations is an 18th Century Document (1758); the Common Law dates to the 12th Century; and concepts about subjects and citizens date back to the Roman Empire.

Further, the Common Law is the Law in the US; Law of Nations is not.

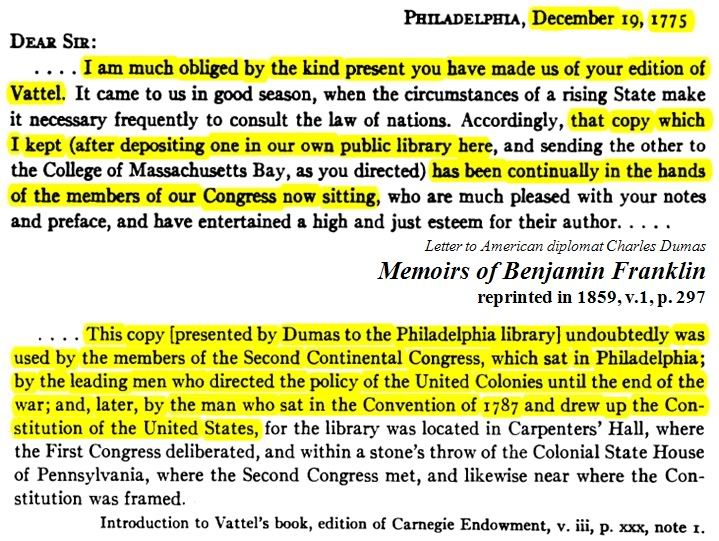

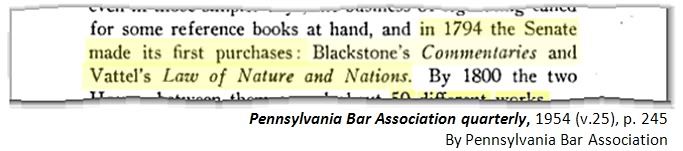

Reason Law of Nations is significant is that the principal drafters of the Constitution were aware of it and had read it and used it as a resource for their work. But the actual legal impact of the terms stands for itself--the concept of a common law subject which was lifted to the Constitution as a citizen is a pure Common Law topic (maybe the founders thought as described in Law of Nations--but the law is the Common Law).

Further, there is another body of law that is also significant and that is Roman law about citizens.

Law of Nations is just another treatise on legal topics of the day--it isn't law; it just purports to be a summary of the author's view of what the law is; real lawyers don't cite that stuff unless they can't come up with real authority to support their argument.

I doubt that Common Law would be viewed as "extending past" but the point of my hypothetical is that there are people out there in the US who have presumably Citizen Parents whose citizen parents are also citizens of another country; and who themselves are citizens of that other country who can still get second country Passports based on their citizenship.

I don't think anything like that would have happened at Common Law although you look at the successors to Edward the III after the death of the Black Prince and see that they were really all French first and wonder.

On the other hand, they clearly did deal with issues about children born outside the country; and children born as subjects to parents who were clearly agents of another sovereign when born and there is commentary in the common law about how those people were addressed.

Various tid bits...

Vattel's "Law of Nations" is based on "natural law." The concept of natural law has been around since the time of the Greeks.

We know that many of the founders and framers were well versed in ancient western civ.

Allegedly, Thomas Jefferson wrote to his nephew that there were three books every gentleman had to have familiarity with; Plutarch's "Lives", Livy's "History of Rome" and Virgil's Aeneid.

"Plato defines justice in the Republic as conforming to nature (Republic, IV, 444d)."

"Aristotle brings to natural law theory an essentially new contribution by deriving the concept of right from the idea of justice, the latter being the appropriate mean that the judge maintains between the parties in court (Nicom. Ethics, Book V, Ch. IV, 8)."

http://etext.virginia.edu/cgi-local/DHI/dhi.cgi?id=dv3-04

I think attorney Apuzzo is spot on here:

The Law of Nations as U.S. Federal Common Law and Not English Common Law Defines What an Article II "Natural Born Citizen" Is

http://puzo1.blogspot.com/2009/08/law-of-nations-and-not-english-common.html

"Natural law or the law of nature (Latin: lex naturalis) is a theory that posits the existence of a law whose content is set by nature and everywhere.[1] [Ed. ex. "All men are created equal"] The phrase natural law is opposed to the positive law (which is human-made) of a given political community, society, or nation-state, and thus can function as a standard by which to criticize that law.[2][Ed. i.e. Declaration of Independence]. In natural law jurisprudence, on the other hand, the content of positive law cannot be known without some reference to the natural law (or something like it). Used in this way, natural law can be invoked to criticize decisions about the statutes, but less so to criticize the law itself. Some use natural law synonymously with natural justice or natural right (Latin ius naturale), although most contemporary political and legal theorists separate the two.

Natural law theories have exercised a profound influence on the development of English common law,[3] and have featured greatly in the philosophies of Thomas Aquinas, Francisco Suárez, Richard Hooker, Thomas Hobbes, Hugo Grotius, Samuel von Pufendorf, John Locke and Emmerich de Vattel [Ed. Both referenced during the Constitutional Convention]. Because of the intersection between natural law and natural rights, it has been cited as a component in United States Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States."

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural_law

Natural law becomes more "defined" during the days of the Romans.

"Evolution of the Roman Legal System and Classical Roman Law"

"As the Roman republic grew and then transformed into an empire, its rulers faced the increasing challenge of governing an evermore diverse and far-flung population. Legal questions and disputes inevitably arose not only among Roman citizens, but with non-citizens living in or traveling through its territories, to whom the ius civile did not apply. This led to the development of the ius gentium ("law of nations") and ius naturale ("natural law")."

http://www.law.berkeley.edu/robbins/RomanLegalTradition.html

Roman law had an influence on British Common law (& Blackstone).

"By the time of the rediscovery of the Roman law in Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries, the common law had already developed far enough to prevent a Roman law reception as it occurred on the continent.[30] However, the first common law scholars, most notably Glanvill and Bracton, as well as the early royal common law judges, had been well accustomed with Roman law...

The impact Roman law had decreased sharply after the age of Bracton, but the Roman divisions of actions into in rem and in personam used by Bracton had a lasting effect and laid the groundwork for a return of Roman law structural concepts in the 18th and 19th century. Signs of this can be found in Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England,[33]"

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Common_law#Medieval_English_common_law

Historical Practice and the Contemporary Debate Over Customary International Law

"...the historical practice of both English and early American courts with respect to the law of nations."

"I. Judicial Power in the Early Republic

First, the history. Professors Bellia and Clark argue that the founding generation entertained an "initial assumption that the United States—like the states—had received the common law and thus could prosecute and punish common law crimes, including offenses against the law of nations."6 Bellia and Clark acknowledge that this assumption was widely rejected in the course of debates over the constitutionality of the Sedition Act.7 Indeed, when the Supreme Court definitively interred the doctrine of federal common law crimes in the 1812 case of United States v. Hudson & Goodwin, it could say that the question already had long been "settled in public opinion."8

A related debate in the early Republic, however, suggests even greater hostility to the idea of federal common lawmaking powers. As Justice Souter has pointed out, "the founding generation . . . join[ed] . . . an appreciation of its immediate and powerful common-law heritage with caution in settling that inheritance on the political systems of the new Republic."10 The colonial and early state governments carefully limited their reception of English common law to those principles that were applicable to local conditions.11 Citizens of the young Republic often viewed the common law with considerable hostility; after all, they had just fought a revolution to throw off English rule..."

This ambivalence played out in debates over ratification of the new national Constitution. All participants seem to have understood that the new federal Constitution did not receive the English common law as part of national law,13 unlike many of the state constitutions. Opponents of ratification went so far as to complain that the proposed document failed to guarantee common law rights.14 Federalists responded that receiving the common law into the federal Constitution would trample the diversity of the common law, as received in the several states; even worse, a federal reception would render the common law "immutable" and not subject to congressional revision.15 Hence, "the Framers chose to recognize only particular common-law concepts, such as the writ of habeas corpus, U.S. Const. Art. I, § 9, cl. 2, and the distinction between law and equity, U.S. Const., Amdt. 7, by specific reference in the constitutional text."16 They insisted, however, that any general reception of the English common law into federal law would be "destructive to republican principles."17

...More generally, the early American reaction to the common law in both the Federal Constitution and the states suggests a general suspicion of unwritten, judge-defined law and a strong preference for legislative primacy. This is quite consistent, of course, with the Framers' decision explicitly to authorize Congress to "define and punish . . . Offenses against the Law of Nations."18

Much more here:

http://www.columbialawreview.org/articles/historical-practice-and-the-contemporary-debate-over-customary-international-law

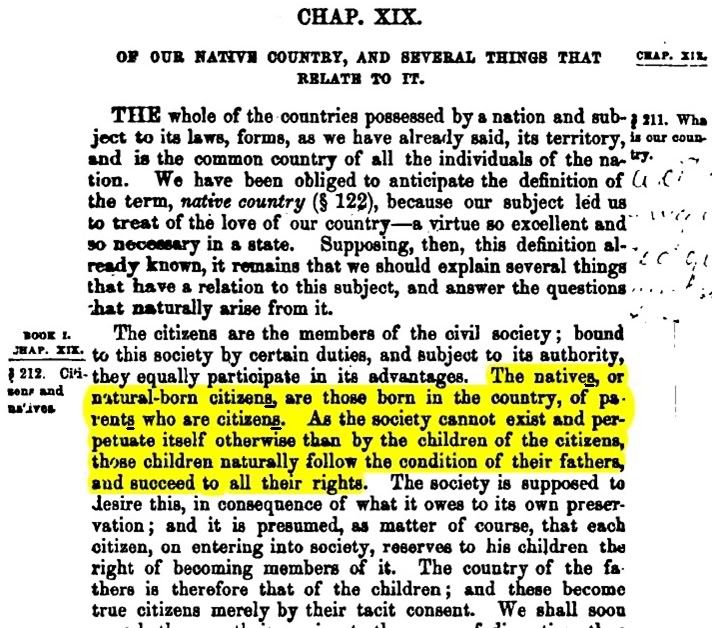

No question in my mind that the framers clearly got their definition for "Natural" born citizen from Vattel's compilation of natural law.