Skip to comments.

Attack On Europe: Documenting Russian Equipment Losses During The 2022 Russian Invasion Of Ukraine (2 year anniversary)

ORYX ^

| Since February 24, 2022 and daily

| ORYX

Posted on 02/24/2024 5:59:01 AM PST by SpeedyInTexas

click here to read article

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first previous 1-20 ... 21,201-21,220, 21,221-21,240, 21,241-21,260, 21,261-21,276 next last

To: GBA

“it’s looking more and more like he will be taking Russia down along with him.”

THat is how it looks to me too.

Sad.

It is atrocious how that clique in the Kremlin wastes the lives and wealth of the people they dominate.

To: SpeedyInTexas

WTI dropped back below $60 today during trading, despite big customers dropping Russian deliveries, and entering the market for spot replacements.

The replacement for Russian oil supply keeps coming online, like gangbusters.

BP started up 5 big fields around Kirkuk, Iraq, just this month (328,000 bpd), right on the heels of Total’s new $27 Billion project, and the resumption of flows from Iraqi Kurdistan through Turkey. The lifting cost of many of these barrels will be at or close to Iraq’s average of $2-4 per barrel (pb), which is about the lowest such cost in the world, along with Iran and Saudi Arabia. No way that Russia can compete with that in the future, in an open market. The Iraqi crude is higher quality as well.

Brazil is breaking records, etc., etc.. The market is ready with replacement supply, and everyone wants a piece of Russia’s market share.

In another week, sub-zero nights set in, up in Novy Urengoy, where the Russian oil pipelines originate.

To: BeauBo

To: gleeaikin

The people who come here to propagandize about mighty Muscovy need to look at the 28 minute video

—

Sim cards don’t look at anything ...

21,244

posted on

10/28/2025 3:11:04 PM PDT

by

PIF

(They came for me and mine ... now its your turn)

To: gleeaikin

But but but the usuals say only the CIA interferes in other countries or elections😂😂😂

To: BeauBo

I am sure that one of our resident usuals will post the graphic on oil prices to confirm this, and the other on Russian how GDP is “surging” 😂😂😂😂

To: BeauBo

Very true, many nations in and out of OPEC+ have been ramping up oil production, including the US.

When pitin is gone maybe Russia will be able to contribute again in a productive and peaceful way, for the world, but also for the average Russian citizen

To: PIF; BeauBo; blitz128; gleeaikin

Кремлевская табакерка

Russia needs another 3-4 years of the NWO and two waves of mobilization

Valery Gerasimov said this in a conversation with Vladimir Putin. The Chief of the General Staff answered the president's question about what is needed for our Victory in the NWO. “Vladimir Vladimirovich asked what we need for the Victory and the achievement of the main goals of the NWO. Valery Vasilyevich replied that, according to his calculations, it was necessary to fight for another 3-4 years. During this time, it is necessary to carry out at least two serious waves of mobilization, one is highly desirable to begin before the end of the year or at the beginning of 2026 (Gerasimov remains a supporter of mobilization - ed.). Vladimir Vladimirovich assured that he took note of these words and would think about them,” a source close to Gerasimov told us. What decisions Putin will make after this conversation, he does not know.

At the same time, the military confirms: what we warned about is happening. There are more and more supporters of ending hostilities without Victory in the NWO and stopping them along the front line. “Vladimir Vladimirovich now harshly rejects such opinions. I hope it will be so in the future,” said another source in Gerasimov’s entourage.

https://t.me/kremlin_secrets/6351

During Mikhail Gorbachev's historic visit to East Germany on the occasion of the GDR’s 40th anniversary, he met with the SED politburo. In his remarks, Gorbachev urged reform and uttered what would become one of the most famous phrases of the period: “Life itself will punish us if we are late.”

Using a variety of analogies, Gorbachev lectured the East German politburo that the only course moving forward was a course of reform. He spoke of his own attempt to initiate reforms in an attempt to ease the tension with the nationalities in the USSR. He also pointed out that opportunities for reform were missed in both Poland and Hungary - where the democratic forces had made even more headway than in the GDR. All of this was meant to serve as a warning to the East German leadership - the only path forward was reform.

https://1989.rrchnm.org/items/show/422.html

21,248

posted on

10/28/2025 3:59:37 PM PDT

by

AdmSmith

(GCTGATATGTCTATGATTACTCAT)

To: BeauBo

You have reached the majors, usuals memeing about you, just wonder where the GDP and oil prices soaring reports are😂😂😂😂

To: blitz128

21,250

posted on

10/28/2025 4:26:20 PM PDT

by

AdmSmith

(GCTGATATGTCTATGATTACTCAT)

To: gleeaikin

21,251

posted on

10/28/2025 4:40:53 PM PDT

by

AdmSmith

(GCTGATATGTCTATGATTACTCAT)

To: AdmSmith

To: bobo; stupid; dimwit; moron; Shill; Buffoon

What happened to recent Party Line that it was not? That Urals grade was REQUIRED? Tell us that you don't know anything about industry without telling us, bobo, you Buffoon Ukie Shill.

21,253

posted on

10/28/2025 5:28:47 PM PDT

by

kiryandil

(No one in AZ that voted for Trump voted for Gallego )

To: bobo

21,254

posted on

10/28/2025 5:32:29 PM PDT

by

kiryandil

(No one in AZ that voted for Trump voted for Gallego )

To: BeauBo

To: AdmSmith

Congrats on beating the 🍈 to top of the page, or maybe his SIM card has been deactivated 😂😂

To: bobo

🍈

Demokratizatsiya was a policy of political liberalization introduced by Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev at the Central Committee plenum of January 28–30, 1987, aimed at infusing democratic elements such as multi-candidate elections and secret ballots into the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) structure to rejuvenate party personnel and broaden societal participation while maintaining the party's monopoly on power.[1][2] The reform sought to address the stagnation of the Brezhnev era by permitting competitive selections for local soviet and party offices, though initial proposals were diluted by conservative CPSU delegates resistant to genuine choice.[1] From mid-1988, demokratizatsiya integrated with perestroika's economic restructuring and glasnost's openness, enabling the formation of unofficial groups (neformaly), which numbered over 30,000 by early 1988 and spurred the emergence of independent political entities like the Democratic Union in May 1988.[3][2] This culminated in the USSR's first competitive elections in March 1989 for the Congress of People's Deputies, where figures like Boris Yeltsin gained prominence despite CPSU opposition, marking a shift toward reduced party control over nominations.[3] However, the policy's half-measures failed to consolidate authority, instead eroding CPSU legitimacy by amplifying public criticism, nationalist movements in republics like the Baltics, and elite divisions.[4] Intended to strengthen the Soviet system through controlled democratization, demokratizatsiya inadvertently accelerated its disintegration by fracturing central power, fueling separatist declarations, and contributing to the failed August 1991 hardliner coup, which paved the way for the USSR's dissolution in December 1991 and Gorbachev's resignation.[4][3] The reforms exposed deep structural flaws in the command economy and one-party rule, leading to economic chaos from incomplete perestroika and political fragmentation rather than the anticipated renewal.[3][4]

Background and Conceptual Foundations

Mikhail Gorbachev was elected General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) on March 11, 1985, following the death of Konstantin Chernenko, amid a backdrop of deepening economic and systemic stagnation inherited from the Brezhnev era. The Soviet economy, characterized by a centralized command structure, had experienced decelerating growth rates, with annual GNP expansion dropping from approximately 5% in the 1960s and early 1970s to 3.7% during 1970–1975, 2.6% in 1975–1980, and 2.0% in 1980–1985, reflecting diminished factor productivity and structural inefficiencies. Contributing factors included widespread corruption within party and state apparatuses, chronic low labor productivity due to the absence of market incentives, and a technological lag that hindered competitiveness against Western innovations, as evidenced by the Soviet Union's reliance on oil exports and failure to modernize heavy industry effectively.[5][6] Gorbachev's initial response emphasized perestroika (restructuring), targeting economic revitalization by addressing the command economy's inherent rigidities, such as over-centralized planning and bureaucratic resistance to innovation, which stifled resource allocation and enterprise autonomy.[7] He recognized that the stagnation stemmed causally from the system's inability to adapt, prioritizing measures to boost productivity and reduce military overspending to redirect resources toward civilian sectors, though these efforts initially operated within the CPSU's monopoly on power.[8] The 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster on April 26 further underscored the imperative for broader systemic changes, revealing deep-seated issues of information suppression and institutional opacity that exacerbated crises and eroded public trust in the regime's competence.[9] Initial government delays in disclosing the accident's scale highlighted how centralized control prioritized secrecy over accountability, prompting Gorbachev to confront the limitations of economic reforms alone and signaling an emerging necessity for political mechanisms to enable transparency and responsiveness, laying groundwork for subsequent democratization initiatives.[10][11]Relation to Perestroika and Glasnost

Perestroika, launched by Mikhail Gorbachev upon his ascension as General Secretary in March 1985, aimed to restructure the Soviet economy through measures like decentralized decision-making and limited market incentives to combat long-standing stagnation characterized by low productivity and resource misallocation. Despite these intentions, the reforms exacerbated supply chain disruptions, leading to persistent consumer shortages, including notorious bread lines that formed across major cities in the mid-to-late 1980s due to failed harvests, hoarding, and inadequate distribution systems under central planning. These economic pressures created a buildup of public discontent, necessitating political mechanisms to channel grievances and prevent potential revolts, as evidenced by archival records of rationing and queue lengths exceeding hours in urban centers like Moscow and Leningrad.[12][13] Glasnost, introduced in 1986 as a complementary policy of openness, permitted unprecedented media scrutiny of Soviet history, including revelations about the Stalinist purges of the 1930s that claimed an estimated 700,000 to 1.2 million lives through executions and gulag sentences, thereby fostering public discourse on regime crimes previously censored. This exposure empirically boosted critical debate, with newspaper circulations surging and public demonstrations increasing, but it also corroded the Communist Party's legitimacy by highlighting inconsistencies between official narratives and factual atrocities, as reflected in declining internal party morale and high-profile defections among intellectuals and officials who publicly renounced ideological orthodoxy. Without economic successes from perestroika to offset this destabilization, glasnost's transparency amplified skepticism toward centralized authority, setting the stage for broader political experimentation.[14][15] Demokratizatsiya emerged as the explicitly political dimension of Gorbachev's agenda, conceptualized as an expansion of participatory governance beyond the CPSU's monopoly by incorporating multi-candidate elections for local soviets and party positions, intended to infuse reforms with public accountability and renew elite commitment to perestroika and glasnost. Proponents argued that one-party suppression inherently stifled innovation and efficiency, as seen in the USSR's comparative economic underperformance relative to Western growth rates averaging 2-3% annually in the 1970s-1980s versus Soviet near-zero gains, justifying democratization to align incentives with societal needs. Yet causal analysis reveals inherent risks: in a sprawling multi-ethnic state spanning 15 republics with deep-seated resentments, glasnost-enabled criticism without perestroika's promised prosperity accelerated centrifugal forces, delegitimizing the center faster than it could consolidate power through electoral facades.[16][17]January 1987 Central Committee Plenum

The Central Committee Plenum of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), convened on 27–28 January 1987, represented the initial formal endorsement of demokratizatsiya as a core element of Mikhail Gorbachev's reform agenda. In his opening report, Gorbachev positioned democratization as essential to perestroika, describing it as a process to extend "democracy and socialist self-government" across society, thereby mobilizing public initiative against entrenched stagnation and bureaucratic inertia. He argued that without such political renewal, economic restructuring would falter, citing the need to replace superficial administrative tweaks with substantive empowerment of soviets and party organs.[18] Gorbachev outlined specific mechanisms to achieve controlled openness, including secret ballots for electing party secretaries—including first secretaries—up to republic-level plenums, with party committee members empowered to nominate multiple candidates rather than endorsing a single pre-selected figure. This shift aimed to supplant ritualistic, show-of-hands voting with competitive selection, while explicitly preserving CPSU oversight by confining nominations to party channels and barring non-party challengers. He further directed party committees to curtail "unwarranted interference" in local soviet operations, insisting they support soviets as "genuine bodies of power" through non-usurping guidance, thereby granting soviets greater autonomy in territorial governance without severing party dominance.[18][19] To address cadre entrenchment fueling apathy, Gorbachev advocated systematic rotation, calling for an "influx of fresh forces" into the Central Committee, Politburo, and Secretariat from varied professional backgrounds, balanced against retaining experienced personnel. These proposals embodied incrementalism designed to reinvigorate the one-party state by simulating competition internally, predicated on the assumption that limited electoral choice and party vetting could harness public energy without risking systemic fracture—a calculus that overlooked the causal dynamics of suppressed pluralism in rigid authoritarian structures, where even modest concessions historically amplified latent dissent.[18][20]19th CPSU Conference Outcomes

The 19th All-Union Conference of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), convened from 28 June to 1 July 1988 in Moscow, produced resolutions that advanced Gorbachev's democratization agenda by proposing amendments to the 1977 Soviet Constitution. These included establishing the Congress of People's Deputies as the supreme legislative authority, comprising approximately 2,250 deputies elected through a mix of territorial districts and public organizations, with provisions for multi-candidate contests and public nominations for at least one-third of seats to bypass direct party control.[21][22] The measures aimed to strengthen the legislature relative to the party apparatus, with the Supreme Soviet functioning as its standing body, thereby initiating a restructuring of power toward elected soviets.[23] Central to the outcomes was the endorsement of separating party functions from state administration, as articulated in Gorbachev's opening address and subsequent resolutions, which called for transferring managerial and executive roles from CPSU committees to soviets and state bodies to reduce bureaucratic interference.[22] This diluted the nomenklatura system's monopoly on appointments by introducing competitive elements in deputy selection, though the party's constitutional leading role under Article 6 remained intact.[21] Resolutions also urged combating administrative overreach, with delegates approving platforms to limit party dictation in economic and cultural spheres, reflecting empirical pressures from pre-conference debates in informal groups advocating transparency.[24] Voting revealed intra-party fissures, with Gorbachev's core proposals passing by majority but facing resistance from conservative delegates; for instance, amendments on electoral openness garnered support amid heated exchanges, yet failed to achieve unanimity, underscoring tensions between reformers and traditionalists like Yegor Ligachev.[23] Empirical data from delegate tallies showed over 80% approval for democratization planks, empowering Gorbachev's faction while exposing vulnerabilities, as evidenced by subsequent rises in critical voices within the party.[25] These outcomes prioritized verifiable institutional tweaks over radical pluralism, setting the stage for limited power diffusion without authorizing multi-party competition.[21]Institutional and Electoral Changes

Establishment of the Congress of People's Deputies

The constitutional amendments adopted by the USSR Supreme Soviet on December 1, 1988, fundamentally restructured the legislative framework by establishing the Congress of People's Deputies as the supreme organ of state power, comprising 2,250 deputies.[26] [21] This body replaced the prior bicameral Supreme Soviet system, with the Congress convening in short sessions approximately twice per year to set policy directions, while delegating routine governance to a smaller, 542-member USSR Supreme Soviet elected from its ranks.[27] Deputies were selected through a hybrid mechanism: 1,500 via direct elections in territorial constituencies of roughly equal population size, and 750 indirectly by all-union public organizations, including the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), trade unions, and academies, allocated proportionally to membership.[28] [29] This allocation ensured that approximately one-third of seats remained under the influence of established institutions loyal to the CPSU, preserving elite control amid the introduction of limited contestability in the majority direct seats. The initial Congress session opened on May 25, 1989, under Mikhail Gorbachev's chairmanship, with proceedings broadcast live on television to promote transparency and public scrutiny of debates.[30] The design sought to reconcile expanded representation with centralized authority, positioning the Congress as a deliberative forum for glasnost-era accountability while subordinating it to CPSU oversight via Article 6 of the Constitution, which enshrined the Party's "leading role" until its repeal by the Congress itself on March 14, 1990.[31] [32] This retention of Party monopoly—despite nominal electoral innovations—critics, including reformist deputies and Western analysts, identified as a core structural limitation, as indirect seats and nomenklatura vetting perpetuated de facto one-party dominance, fostering perceptions of democratic theater rather than substantive power diffusion. Empirical outcomes bore this out: pre-1990 sessions revealed vigorous intra-Party debates but no challenge to core authoritarian mechanisms, underscoring the reform's causal shortfall in eroding entrenched hierarchies without complementary institutional safeguards.[33] [34]Introduction of Multi-Candidate Elections

The introduction of multi-candidate elections formed a core component of Mikhail Gorbachev's demokratizatsiya policy, aiming to enhance accountability within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) by permitting competition for soviet and party posts without establishing rival political parties.[35] This reform, formalized through the Law on Elections to the USSR People's Deputies adopted on December 1, 1988, applied to both the newly created Congress of People's Deputies and local soviets, replacing the prior single-candidate system that had ensured unopposed victories since the 1920s.[36] Nominations originated from public organizations, work collectives, and CPSU primaries, with district-level meetings required to advance candidates via open presentations and voting; if multiple nominees exceeded the seat allocation, voters selected one candidate per seat in secret ballots, requiring an absolute majority for victory or triggering runoffs between the top two contenders.[37] Initially structured as non-partisan contests—where all candidates, whether CPSU members or "independents," operated under the party's overarching monopoly—these elections lacked independent electoral oversight, relying instead on CPSU-controlled commissions for validation, nomination filtering, and dispute resolution, which preserved elite influence over outcomes despite procedural openness.[35] Official Soviet reports indicated that over 80% of races featured multiple contenders at the nomination stage during the 1988-1989 rollout, reflecting deliberate efforts to simulate competition while containing it within loyalist bounds.[38] However, the absence of comprehensive electoral legislation—such as codified campaign finance rules, impartial media access guarantees, or judicial recourse mechanisms—meant processes were ad hoc and susceptible to local party interference, undermining the intended feedback loop from voters to apparatchiks. Under the banner of glasnost, these mechanics inadvertently exposed CPSU incumbents to public criticism during nomination debates and campaigns, shifting leverage away from entrenched bureaucrats toward candidates willing to voice reformist or localized grievances, as seen in urban centers like Moscow where scrutiny eroded traditional patronage networks.[39] This empirical redistribution of authority, while nominally reinforcing party legitimacy, sowed instability by introducing competitive pressures without institutional safeguards, as evidenced by procedural irregularities and post-election challenges that highlighted the fragility of rule-bound transitions in a centralized system devoid of pluralistic precedents.[17]Emergence of Political Pluralism

The Inter-Regional Deputies' Group (IRDG), the Soviet Union's first organized parliamentary faction advocating systemic reforms, emerged on June 9, 1989, amid the final sessions of the inaugural Congress of People's Deputies. Comprising 388 deputies—roughly 10% of the Congress total—the group coalesced from reform-minded participants who prioritized market-oriented economic restructuring, separation of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) from state administration, and enhanced democratic processes over continued central planning.[40] [31] Initial co-chairmen included physicist and dissident Andrei Sakharov, historian Yury Afanasyev, and economist Gavriil Popov, with Boris Yeltsin later joining the leadership in July.[40] [41] The IRDG's platform, debated publicly starting July 30, 1989, called for devolving political authority to elected soviets, critiquing the CPSU's monopoly on power and the failures of command economies in fostering inefficiency and stagnation.[42] [41] Group members leveraged the Congress's unprecedented live television coverage to amplify these arguments, exposing public discourse to critiques of Party overreach and demands for legal safeguards akin to human rights standards.[31] This visibility marked a causal shift from opaque elite decision-making to broader scrutiny, though the faction's roughly 400 members across Congress and Supreme Soviet bodies remained outnumbered by CPSU loyalists.[31] Primarily drawing from urban intelligentsia and non-Party professionals elected via competitive ballots, the IRDG embodied pushback against Gorbachev-era constraints, yet its efficacy was empirically curtailed by institutional CPSU dominance, which retained veto power over legislative outcomes.[40] [31] The group's advocacy overestimated liberal reform's resonance in a populace shaped by decades of conservative indoctrination and material hardships, yielding rhetorical gains but minimal policy concessions amid entrenched resistance.[41]The relaxation of controls under glasnost from 1987 onward facilitated the emergence of informal associations, initially as discussion clubs and hobby groups that gradually politicized. These entities, often centered in urban areas like Moscow and Leningrad, provided platforms for debating reforms, economic privatization, and critiques of Soviet history, marking a departure from the monolithic CPSU dominance.[43] By late 1988, such groups had proliferated, with opposition-oriented ones challenging official narratives on issues like historical accountability.[44] A key example was the Democratic Union, established on May 8, 1988, by dissidents including Valeriya Novodvorskaya, positioning itself as the first openly anti-communist organization and advocating multiparty democracy without allegiance to the regime.[45] Similarly, the Memorial Society, founded in August 1987 as the Group to Establish the Tradition of the Victims of Political Repression, documented Stalin-era crimes and Gulag atrocities, enabling public acknowledgment of Soviet repression that had long been suppressed.[46] These associations drew from dissident networks and intelligentsia circles, fostering environments where participants aired grievances over past abuses and proposed alternatives like market-oriented changes, though their influence remained limited by legal ambiguities and state surveillance.[47] The March 14, 1990, repeal of Article 6 of the USSR Constitution, which had constitutionally mandated the CPSU's "leading and guiding role," removed the primary legal barrier to organized opposition.[48] This amendment, passed by the Congress of People's Deputies amid Gorbachev's maneuvers to counter hardliners, permitted informal groups to evolve into proto-parties by allowing formal registration and multiparty structures.[49] Organizations like Democratic Union expanded activities, while others, including liberal and social-democratic clubs, began structuring hierarchies and platforms, shifting from ad hoc gatherings to embryonic political entities.[50] While this openness unearthed empirical truths about Soviet crimes—such as through Memorial's archival work—it accelerated factionalism in a polity lacking institutional norms for pluralism, resulting in fragmented advocacy that prioritized ideological purity over coordinated action.[51] Rapid proliferation in an authoritarian-inherited society, where habits of conformity persisted, engendered paralysis by diluting unified reform efforts and amplifying divisive debates on privatization and autonomy without adequate mechanisms for resolution.[43]Escalation into Crisis (1989-1991)

1989 Competitive Elections and Results

The nationwide elections for the Congress of People's Deputies commenced on 26 March 1989, with run-off votes on 2 April and supplementary polls extending to 23 May in constituencies lacking an absolute majority winner, contesting 1,500 directly elected seats out of 2,250 total.[27] Voter turnout reached 89.8 percent in the initial round, reflecting both public curiosity toward the novel multi-candidate format and residual habits of compulsory participation under the prior system.[27] In urban centers like Moscow and Leningrad, outcomes surprised authorities, as voters rejected numerous high-ranking Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) nominees; for instance, nearly all party officials in Moscow districts were defeated, while in Leningrad every regional party, soviet, and military leader lost their bids.[52] Notable upsets included Andrei Sakharov's victory in a Moscow constituency after a contentious run-off against the endorsed candidate, and Boris Yeltsin's landslide win with approximately 90 percent support in his district.[53][52] Despite these defeats signaling widespread discontent with entrenched elites—particularly over delays in perestroika implementation—the results underscored limited penetration of competitive pluralism.[52] Approximately 85 percent of elected deputies were CPSU members, bolstered by the allocation of 750 seats to party-controlled public organizations and the prevalence of uncontested or minimally opposed races in rural and peripheral areas.[52][27] Reform-oriented independents and informal groups secured footholds in major cities, enabling subsequent advocacy for transparency and economic overhaul, yet the CPSU retained de facto control through organizational discipline and the 1,500-seat threshold's structure favoring incumbency networks. The elections also exposed deepening ethnic fissures, as nationalist fronts in the Baltic republics—such as Estonia's ENIP—organized boycotts of the Soviet poll, protesting its legitimacy and advocating republican sovereignty instead, which depressed participation and amplified regional autonomy demands.[54] Empirical analysis reveals the process's superficiality beyond urban anomalies: over 76 constituencies required run-offs due to fragmented votes failing absolute majorities, while bloc-style endorsements and pre-election blacklists in areas like Armenia constrained choice, per internal party assessments.[27][52] High turnout, while indicative of engagement, coexisted with reports of coerced mobilization and voter lists inflated by state enterprises, suggesting enthusiasm was tempered by systemic inertia rather than robust contestation; declassified Politburo discussions acknowledged these as "exceptional" but framed defeats as localized reactions to unmet expectations, not systemic repudiation.[52] Thus, the polls registered public frustration empirically—via official tallies of elite ousters—but preserved CPSU hegemony, prioritizing continuity over disruption in a federation already straining under Gorbachev's reforms.[52]Nationalist Sovereignty Declarations in Republics

The liberalization under demokratizatsiya, particularly the 1989 introduction of multi-candidate elections to local soviets and the Congress of People's Deputies, enabled nationalist elites to capture republican legislatures, amplifying long-suppressed ethnic grievances and precipitating declarations of sovereignty that prioritized local authority over central control.[55] On March 11, 1990, Lithuania's Supreme Council declared the restoration of the independent state of Lithuania, nullifying Soviet annexations since 1940 and asserting full sovereignty, a move enabled by the republic's February 1990 elections where pro-independence Sajudis candidates secured 125 of 141 seats.[56] [57] This initiated a "parade of sovereignties," with the Russian SFSR's First Congress of People's Deputies adopting a Declaration of State Sovereignty on June 12, 1990, proclaiming the supremacy of RSFSR laws, ownership of natural resources, and the right to veto all-union legislation conflicting with republican interests.[58] [59] Ukraine followed on July 16, 1990, when its Verkhovna Rada issued the Declaration of State Sovereignty, affirming the Ukrainian nation's self-determination, the indivisibility of republican power, and economic independence from Moscow.[60] [61] By late summer 1990, all 15 union republics had enacted comparable declarations, often citing USSR Congress laws from April and September 1990 that permitted economic autonomy and state sovereignty as legal pretexts.[62] Electoral outcomes from 1989-1990 served as empirical triggers, as competitive polls in republics like the Baltics revealed widespread rejection of union subordination; in Lithuania's March 1990 supreme soviet vote, nationalist forces dominated, mirroring Latvia and Estonia where pro-sovereignty candidates won supermajorities in analogous early 1990 elections, channeling public support rooted in deportations, Russification, and forced collectivization under Soviet rule.[63] These assertions reflected causal dynamics wherein political openness, absent robust institutional safeguards against secession, mobilized historical resentments—such as the 1940 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact annexations—eroding the USSR's unitary framework and rendering Gorbachev's vision of asymmetric federalism untenable in a polity fractured by ethnic hierarchies and resource disputes.[55] The declarations directly impeded union treaty negotiations, as republics conditioned participation on maximal devolution, with Russia's sovereignty claim blocking centralized fiscal powers and Ukraine's emphasizing neutrality and separate military forces, ultimately dooming drafts for a "Union of Sovereign States" by exposing the impracticality of renegotiating cohesion amid diverging sovereignty imperatives.[55] [64] Gorbachev's federalist concessions, intended to accommodate autonomy within a preserved union, overlooked first-order incentives for republics to exploit openness for outright separation, accelerating imperial disintegration as local legislatures prioritized constituent power over collective treaty obligations.[55]Controversies and Empirical Critiques

Erosion of Central Control and Elite Morale

Following the competitive elections to the Congress of People's Deputies in March 1989, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) experienced a rapid erosion of its authority among elites, manifested in widespread defections and declining membership. Once numbering around 19 million adherents, party rolls shrank significantly by 1991 as mid-level officials and intellectuals publicly renounced loyalty amid glasnost-enabled media scrutiny of past abuses and reform failures.[65] Archival evidence from regional committees, such as in Sverdlovsk, documents sharp drops—3.4% in 1989 alone, escalating to 25.5% in 1990 with over 23,000 exits—reflecting broader disillusionment as demokratizatsiya exposed systemic flaws, prompting elites to prioritize personal or regional interests over centralized discipline.[66] Conservative figures within the party, including Politburo member Yegor Ligachev, lambasted Gorbachev's reforms for engendering anarchy and undermining morale, arguing that unchecked openness fragmented unity and invited chaos. Ligachev specifically faulted the program for economic disarray and societal disorder during the February 1990 party congress, where delegates echoed concerns over loyalty erosion.[67] This critique found empirical corroboration in the surge of labor unrest, such as the July 1989 coal miners' strikes involving approximately 400,000 workers across Kuzbass and Donbass regions, which exploited glasnost for public mobilization against shortages and conditions, further straining elite cohesion and central directives.[68] While reform advocates hailed these developments as liberating elite discourse from ideological straitjackets, data on ensuing policy gridlock—evident in stalled Central Committee decisions amid radical-conservative clashes—underscore a causal weakening of CPSU command structures, contradicting narratives of steady progress toward viable pluralism. The influx of non-party deputies into legislative bodies post-1989 amplified factional vetoes, paralyzing executive implementation and demoralizing apparatchiks who witnessed the party's monopoly yield to institutional impotence without compensatory gains in efficacy.[69]Interlinkages with Economic Stagnation and Chaos

The political reforms of demokratizatsiya, intertwined with glasnost, unfolded amid deepening economic distress from 1989 to 1991, as perestroika's partial market incentives failed to resolve chronic shortages and output declines. Consumer goods scarcity intensified, with supermarkets featuring empty shelves for staples like meat, dairy, and toilet paper, a problem exacerbated by monetary overhang from suppressed prices and inefficient central planning.[12][70] Glasnost's relaxation of censorship amplified public awareness of these deficiencies, spurring widespread complaints in media and informal discourse that highlighted systemic failures but also eroded worker morale and enterprise discipline.[70][71] Economic indicators reflected this turmoil: gross national product contracted by approximately 20% between 1989 and 1991, with national income following suit, signaling a shift from stagnation to outright contraction.[72] Inflationary pressures mounted as price controls loosened, culminating in accelerating rates by 1991 that strained savings and fueled hoarding behaviors among households anticipating further devaluation.[73][74] Reform advocates, including Gorbachev-era officials, often attributed woes to entrenched party bureaucracy, yet empirical data on production shortfalls—such as a 25% drop in trade with Eastern Europe in 1990—indicated that demokratizatsiya's encouragement of open criticism and factionalism diverted focus from stabilizing supply chains, indirectly worsening panic buying and inventory disruptions.[75] From a causal standpoint, introducing competitive elections and pluralistic debate without prior economic stabilization primed backlash, as public venting of grievances intensified perceptions of crisis and undermined incentives for productivity in state enterprises.[76] While these reforms achieved tangible gains in reducing censorship and fostering debate on inefficiencies, the primacy of material prosperity in sustaining political legitimacy—evident in pre-reform eras of growth—suggests that prioritizing demokratizatsiya over sequenced economic fixes amplified chaos rather than mitigating it.[76][71]August 1991 Coup Attempt

On August 19, 1991, a faction of Soviet hard-line officials, including KGB chairman Vladimir Kryuchkov, Defense Minister Dmitry Yazov, and Interior Minister Boris Pugo, initiated a coup d'état against President Mikhail Gorbachev by placing him under house arrest at his Crimean dacha while he was vacationing there.[77] The plotters formed the State Committee on the State of Emergency (GKChP), which announced Gorbachev's temporary incapacity due to illness and declared a state of emergency to prevent the signing of a new union treaty scheduled for August 20 that would have devolved significant powers to the republics amid escalating separatist pressures from Gorbachev's democratization reforms.[4] Justifying their actions as a necessary measure to avert national chaos and disintegration fueled by unchecked political pluralism and economic turmoil, the GKChP deployed tanks and troops to Moscow, but the operation lacked unified command and decisive enforcement.[78] Public resistance, spearheaded by Russian President Boris Yeltsin, rapidly undermined the coup; Yeltsin famously climbed atop a tank outside the Russian White House (parliament building) to denounce the plotters and rally demonstrators, drawing tens of thousands to barricades and exposing deep fissures within the military, where many unit commanders refused orders to fire on civilians or advance aggressively.[79] Despite mobilizing substantial forces, the coup resulted in minimal violence, with only three civilian deaths reported during clashes on August 21, highlighting the reformers' success in eroding the regime's coercive monopoly through prior liberalization of media and civic associations.[80] By August 21, key plotters had capitulated or fled, Gorbachev was restored to Moscow, and the failed putsch—intended to reverse the centrifugal dynamics unleashed by demokratizatsiya—ironically discredited central authority further by revealing the Soviet state's internal paralysis and validating hard-liners' warnings of fragmentation even as it hastened their defeat.[81] In the coup's aftermath, Yeltsin moved swiftly to consolidate power, suspending Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) activities across the Russian Republic on August 23, 1991, a decree that effectively gutted the party's organizational structure and symbolized the reforms' culmination in regime delegitimization.[82] This outcome underscored how the hard-liners' desperate bid, rooted in fears of union dissolution amid rising republican autonomy and elite defections, instead amplified those very forces by alienating the military and empowering regional leaders opposed to Gorbachev's faltering centralism.[4]Acceleration Toward USSR Breakup

Following the failure of the August 1991 coup attempt, Soviet republics rapidly advanced toward formal independence, leveraging the political openings created by demokratizatsiya's electoral reforms and sovereignty declarations. On December 1, 1991, Ukraine conducted a nationwide referendum on its August declaration of independence, with 92.3% of voters approving the act amid a turnout of over 84%.[83] This outcome, coupled with similar referenda and parliamentary actions in other republics such as Georgia earlier in the year, underscored the erosion of central authority, as local legislatures invoked the competitive elections and public discourse mechanisms introduced under Gorbachev's policies to legitimize separation.[84] The momentum culminated in the Belavezha Accords, signed on December 8, 1991, by Russian President Boris Yeltsin, Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk, and Belarusian leader Stanislav Shushkevich at a retreat in the Belovezhskaya Pushcha forest. The agreement declared the USSR defunct, established the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) as a loose association of sovereign states, and terminated the 1922 Union Treaty, effectively dissolving the superpower without Gorbachev's direct involvement.[85] On December 21, eleven former republics formalized the CIS in Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan, further sidelining union preservation efforts; Gorbachev resigned as Soviet president on December 25, and the USSR Supreme Soviet voted on December 26 to acknowledge the union's cessation via Declaration No. 142-N.[55] Demokratizatsiya contributed causally by enabling Yeltsin's ascent—through his 1989 election to the USSR Congress of People's Deputies and his June 1991 presidential victory in the Russian SFSR—which amplified anti-centralist forces via open congressional debates that exposed union treaty flaws and empowered republican executives amid the post-coup power vacuum.[55] Proposed revisions to the union treaty, intended for signing on August 20 but derailed by the coup, collapsed as republics prioritized sovereignty, with the Congress of People's Deputies disbanding itself in early September without resolving inter-republical tensions. The core breakup occurred without interstate violence, reflecting the legalistic channels democratizing reforms had institutionalized, though immediate economic fallout included intensified shortages of goods and the ruble's rapid devaluation, exacerbating pre-existing scarcity in food and consumer items.[4][79]Long-Term Legacy and Assessments

Failed Democratization in Successor States

In Russia, the initial post-Soviet push for democratization under President Boris Yeltsin devolved into crisis during the 1993 constitutional standoff, where Yeltsin dissolved the Supreme Soviet on September 21 and ordered military forces to shell the parliament building on October 4, resulting in over 140 deaths and the suppression of legislative opposition. This violent resolution entrenched a super-presidential system via the December 1993 constitution, which granted the executive broad decree powers and weakened checks and balances, paving the way for authoritarian consolidation rather than pluralistic governance.[86][87] Economic liberalization through rapid privatization exacerbated these trends, enabling a handful of insiders to amass control over state assets via corrupt mechanisms like the 1995 loans-for-shares program, where banks lent to the government collateralized by enterprises, later acquiring them at undervalued auctions. This process birthed Russia's oligarch class, concentrating wealth amid hyperinflation and output collapse, with GDP plummeting 40% from 1990 to 1998; inequality surged as the Gini coefficient rose from 0.26 in 1989 to 0.40 by 1996, reflecting distorted resource allocation without rule-of-law safeguards.[88][89][90] Beyond Russia, demokratizatsiya's institutional voids facilitated reversion to authoritarianism in most successor states, notably Central Asia's five republics—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan—which by 2024 were uniformly rated as consolidated authoritarian regimes with minimal electoral competition or civil liberties.[91] Empirical assessments indicate only partial successes in the Baltics and limited cases elsewhere, while pervasive regret over the USSR's 1991 dissolution—66% of Russians in a 2019 Levada Center survey—signals widespread perception of ensuing instability, hyperinflation, and eroded social protections as causal fallout from unanchored reforms.[92] Critiques attribute these outcomes to shock therapy's disregard for sequencing, where abrupt liberalization preceded institutional buildup, fostering rent-seeking and elite capture; comparative data show deeper transformational recessions in rapid reformers versus milder contractions under gradualist strategies that prioritized stabilization first.[93][94]Balanced Evaluations of Achievements Versus Systemic Collapse

Demokratizatsiya, alongside glasnost, facilitated the first competitive elections in the Soviet Union in 1989, introducing multi-candidate contests for local Communist Party positions and Soviets, which eroded the absolute monopoly of one-party rule.[3][95] Glasnost enabled unprecedented public discourse, including criticism of Stalin-era atrocities, and prompted the declassification of Gulag archives between 1989 and 1990, revealing demographic data on camp populations and forced labor contributions previously suppressed.[96][97] These reforms also expanded media freedoms, allowing newspapers and journals to disseminate uncensored news and air national grievances without immediate reprisal by late 1980s standards.[98][99] However, these political openings exacerbated systemic instability, as perestroika's partial market experiments without dismantling central planning led to supply disruptions and hyperinflation, contributing to a 20% gross national product decline across Soviet republics from 1989 to 1991.[72][100] The ensuing economic chaos in successor states, directly traceable to the reform-induced transition, saw Russian male life expectancy plummet from 63.4 years in 1991 to 57.4 years by 1994 amid surging mortality from alcohol-related causes and social dislocation.[101] Demokratizatsiya's empowerment of republican nationalism accelerated the USSR's dissolution in December 1991, resulting in the loss of empire over 14 non-Russian republics and fueling ethnic conflicts, such as those in the Caucasus and Central Asia, without mechanisms for managed federal restructuring.[102] Assessments diverge sharply, with Gorbachev's defenders crediting the reforms f

To: PIF; BeauBo; blitz128; gleeaikin

Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, October 28, 2025

Russian forces recently advanced in southeastern Myrnohrad (east of Pokrovsk), but these advances are unlikely to cause an immediate collapse of the Ukrainian pocket in the Pokrovsk direction. Geolocated footage published on October 27 and 28 indicates that Russian forces recently advanced into the southeastern outskirts of Myrnohrad.[1] A Russian milblogger claimed that Russian forces advanced in northern and eastern Pokrovsk and northeastern Myrnohrad.[2] The Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) claimed that elements of the 5th Motorized Rifle Brigade (51st Combined Arms Army [CAA], formerly 1st Donetsk People's Republic Army Corps [DNR AC], Southern Military District [SMD]) advanced in eastern Myrnohrad and that Ukrainian forces counterattacked near Hryshyne (just northwest of Pokrovsk).[3] Ukrainian Eastern Group of Forces Spokesperson Captain Hryhorii Shapoval reported on October 28 that Russian forces do not have full control over any positions in Pokrovsk, but noted that Russian forces maintain a 10-to-one drone advantage over Ukrainian forces in the Pokrovsk direction.[4] Shapoval’s statement is consistent with ISW’s definition of the assessed Russian advances as verifiable areas in which Russian forces have operated in or conducted attacks against, even if they do not maintain control. Control is doctrinally defined as “a tactical mission task that requires the commander to maintain physical influence over a specified area to prevent its use by an enemy or to create conditions necessary for successful friendly operations.”[5] Russian forces almost certainly do not currently control any positions within the city of Pokrovsk itself.

Russian President Vladimir Putin reportedly demanded Russian forces seize Pokrovsk by mid-November 2025, although Russian forces are unlikely to meet this deadline. Ukrainian sources amplified a since-deleted Financial Times (FT) report that cited unnamed media sources reporting that Putin tasked the Russian military command with taking control of Pokrovsk by mid-November 2025.[6] Russian forces have repeatedly missed Putin's arbitrarily demanded deadlines to seize specific territory in Ukraine, including Putin's early demand to seize all of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts by September 2022.[7] Ukrainian Presidential Office Deputy Head Colonel Pavlo Palisa assessed on June 5, 2025 that Russian forces aimed to seize an operationally significant area of Donetsk Oblast (including Slovyansk, Kramatorsk, Druzhkivka, Kostyantynivka, and Pokrovsk) by September 1, 2025; the rest of Kherson Oblast and a ”buffer zone” in northern and southern Ukraine by the end of 2025; and all land east of the Dnipro River in northern and eastern Ukraine, as well as most of Mykolaiv and Odesa oblasts by the end of 2026.[8] Russian forces have failed to seize any of these major cities in Donetsk Oblast as of late October 2025, and ISW continues to assess that seizing Ukraine's fortress belt will be a multi-year-long effort for Russian forces.[9] Putin regularly tasks the Russian General Staff with seizing operationally significant swaths of land within unrealistic timeframes, and the timeframe within which Putin aims to seize Pokrovsk is not a realistic reflection of Russian forces’ ability to seize the town.

Russian tactics in Pokrovsk have entrapped civilians within the city, intensifying the risk of indiscriminate civilian harm. The Ukrainian Pokrovsk Military Administration reported that Russian forces have fire control over all egress routes from Pokrovsk, effectively entrapping 1,200 civilians within Pokrovsk.[10] The Pokrovsk Military Administration reported that Russian forces are killing civilians who attempt to evacuate both on foot and in vehicles. Ukrainian Eastern Group of Forces Spokesperson Captain Hryhorii Shapoval reported that Russian forces are wearing civilian clothes as part of deception tactics that may amount to perfidy, a war crime that the Geneva Convention defines as “acts inviting the confidence of an adversary to lead him to believe that he is entitled to, or is obliged to accord, protection under the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict, with intent to betray that confidence.”[11] Russian forces’ systematic resort to perfidy in Pokrovsk has added a significant degree of confusion and chaos to the area, likely putting Ukrainian civilians at even greater risk of harm. The drone saturation in the skies over Pokrovsk also poses an intensified threat to the safety of civilians, especially as Russian forces frequently use drones to purposefully target civilians.[12] ISW has previously observed reports that Russian forces indiscriminately target both civilian and military vehicles traveling in frontline oblasts and that the indiscriminate strikes on vehicles complicate or block medical services and evacuations from the frontlines.[13]

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky announced on October 28 that Ukraine and Sweden agreed to localize production of Swedish Gripen fighter jets in Ukraine.[14] Zelensky noted that training for Ukrainian pilots to operate Gripens lasts six months and that Gripens require a small maintenance team.[15] Zelensky announced on October 25 that Ukraine also expects Sweden to begin delivering its promised 150 Gripen fighter jets to Ukraine in early 2026. Zelensky stated on October 28 that he is also in talks with France to supply Rafale fighter jets to Ukraine.[16]

The Kremlin is resurrecting Soviet-era narratives of Russia's perpetual victimhood in the face of perceived external aggression in a dual attempt to justify Russia's future aggression against both Europe and the Asia-Pacific and the longer-term mobilization of Russian society. Russia's Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) baselessly claimed on October 28 that France is preparing a military contingent of 2,000 servicemen to send to Ukraine.[17] The SVR specifically claimed that these forces are part of the French Foreign Legion, which Russian milbloggers have previously claimed are operating in Ukraine — part of the Kremlin's concerted effort to justify claims that Russia is fighting all of NATO, not just Ukraine.[18] The Kremlin often uses the SVR to spread unfounded allegations designed to weaken support for Ukraine and sow doubt about the nature of Russia's own provocations against NATO member states.[19] The SVR has been releasing public statements about supposed Western provocations against Russia more frequently since mid-September 2025, constituting a concerted pattern of activity that is likely part of Russia's “Phase Zero” informational and psychological condition-setting phase for a higher level of NATO-Russia conflict.[20]

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov reiterated claims on October 28 that NATO remains a significant threat to Russia, including by admitting new members and supplying Ukraine with weapons and financial and political support.[21] Lavrov claimed that NATO is artificially expanding its area of responsibility (AoR) beyond the Euro-Atlantic, including to the Indo-Pacific, Middle East, South Caucasus, and Central and South Asia, with the goal of containing the People's Republic of China (PRC), isolating Russia, confronting North Korea, and broadly expanding its influence. Russian Security Council Secretary Sergei Shoigu claimed on October 28 that Russia is currently countering aggressive external pressure and anti-Russian propaganda from the West and that the West is trying to divide Russia into a series of “ethno-states.”[22] These narratives are not new, and in fact call back to the Soviet Union's rhetorical justifications for the Cold War as the answer to being “surrounded by enemies.”[23] The SVR’s, Lavrov’s, and Shoigu’s resurrection of Soviet-era narratives that Russia must protect itself against perceived global threats supports the Kremlin's wider efforts to generate domestic support for a protracted war in Ukraine and a future military conflict against NATO.[24]

Russian officials also appear to be setting conditions to justify further militarization and full-scale mobilization of Russian society. Shoigu later claimed during a meeting in Nizhny Novgorod Oblast that foreign intelligence agencies are attempting to infiltrate critical Russian infrastructure — including defense industrial base (DIB) enterprises, transportation facilities, and energy companies — to commit sabotage and steal strategic information from Russia.[25] Shoigu noted that Russia may call up reservists to protect critical Russian infrastructure. Russian authorities previously claimed that Russia intended to mobilize reservists to protect critical infrastructure from Ukrainian strikes and appear to be broadening this justification to also defending against alleged Western spies.[26] Russian authorities will likely leverage the threat of Western agitators in Russia to justify greater societal repressions and garner additional support for mobilizing reservists.

The Russian State Duma approved a bill on October 28 allowing Russian authorities to recruit members of Russia's “human mobilization reserve” to protect Russian critical facilities and infrastructure.[27] Russia's “human mobilization reserve” is Russia's higher-readiness active reserve in which Russian citizens sign a contract with the Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) on a voluntary basis to serve in the reserve while remaining civilians except when called up.[28] The bill states that reservists will participate in special training sessions to ensure the production of critical facilities and that the Russian government will establish the training procedures for reservists. Deputy Chief of the Russian General Staff's Main Organizational and Mobilization Directorate, Vice Admiral Vladimir Tsimlyansky, stated on October 22 that Russian authorities will send reservists to training camps to prepare to protect critical infrastructure and defend against drones.[29] Tsimlyansky clarified that this bill does not require reservists to participate in military operations or missions outside of Russia. The October 28 bill differs from the Russian MoD’s October 13 draft amendment that requests permission for the Russian military to use members of Russia's “human mobilization reserve” in expeditionary deployments outside of Russia without an official Kremlin declaration of mobilization or state of war, which the State Duma has not approved as of this report.[30] It is unclear if the Kremlin will use the October 28 bill to deploy reservists to rear areas of occupied Ukraine, as Russian officials continue to falsely insist that occupied Ukraine is part of Russia.[31] The Kremlin may leverage the October 28 bill as a stepping stone toward mobilizing reservists on a rolling basis to fight in Ukraine, as ISW previously forecasted.[32]

European authorities recently reported unidentified drones near airports in Spain and a military base in Estonia. Authorities at the Miguel Hernández Airport in Alicante, Spain, reported that unidentified drones flying near the runway forced the airport to close on the evening of October 27.[33] Spanish authorities have launched an investigation to determine the drone launch point and the actors responsible. Spanish authorities also reported that the Palma de Mallorca Airport suspended operations on the evening of October 19 after an unidentified drone sighting in the airport's airspace.[34] Estonian General Staff Spokesperson Liis Waxmann reported that authorities detected two unidentified drones flying near the Camp Reedo military base of the Estonian 2nd Infantry Brigade in southern Estonia on the afternoon of October 17.[35] Authorities reportedly shot down one of the drones but could not find the wreckage. Camp Reedo also houses the US 5th Squadron, 7th Cavalry Regiment (5-7 CAV). Neither Spanish nor Estonian authorities have identified the drones as Russian as of this writing.

European officials continue to report on Russian hybrid operations in Europe over the past several years. The Latvian State Security Service (VDD) proposed on October 17 that the Latvian Prosecutor's Office initiate criminal prosecution against four individuals who planned and committed arson attacks against Latvian facilities in 2023 and 2024.[36] The VDD investigation, which began in June 2024, found that the group conducted an arson attack against a private company that was working on a defense-related project in Fall 2023 and prepared an arson attack against a truck with Ukrainian license plates at a critical infrastructure facility in early 2024. The four individuals reportedly conducted the attacks at the initiative of Russian special services and sent reconnaissance data about potential targets to organizers in Russia. Russia has been setting conditions to confront the West for several years, and Russian sabotage and intelligence activities from years past likely support Russia's effort to prepare for a possible NATO-Russia war.[37] ISW assesses that Russia‘s intensified “Phase Zero” effort, Russia's broader informational and psychological condition-setting phase to prepare for a possible NATO-Russia war, began in early September 2025.[38]

more + maps

https://understandingwar.org/research/russia-ukraine/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-28-2025/

21,258

posted on

10/29/2025 12:28:26 AM PDT

by

AdmSmith

(GCTGATATGTCTATGATTACTCAT)

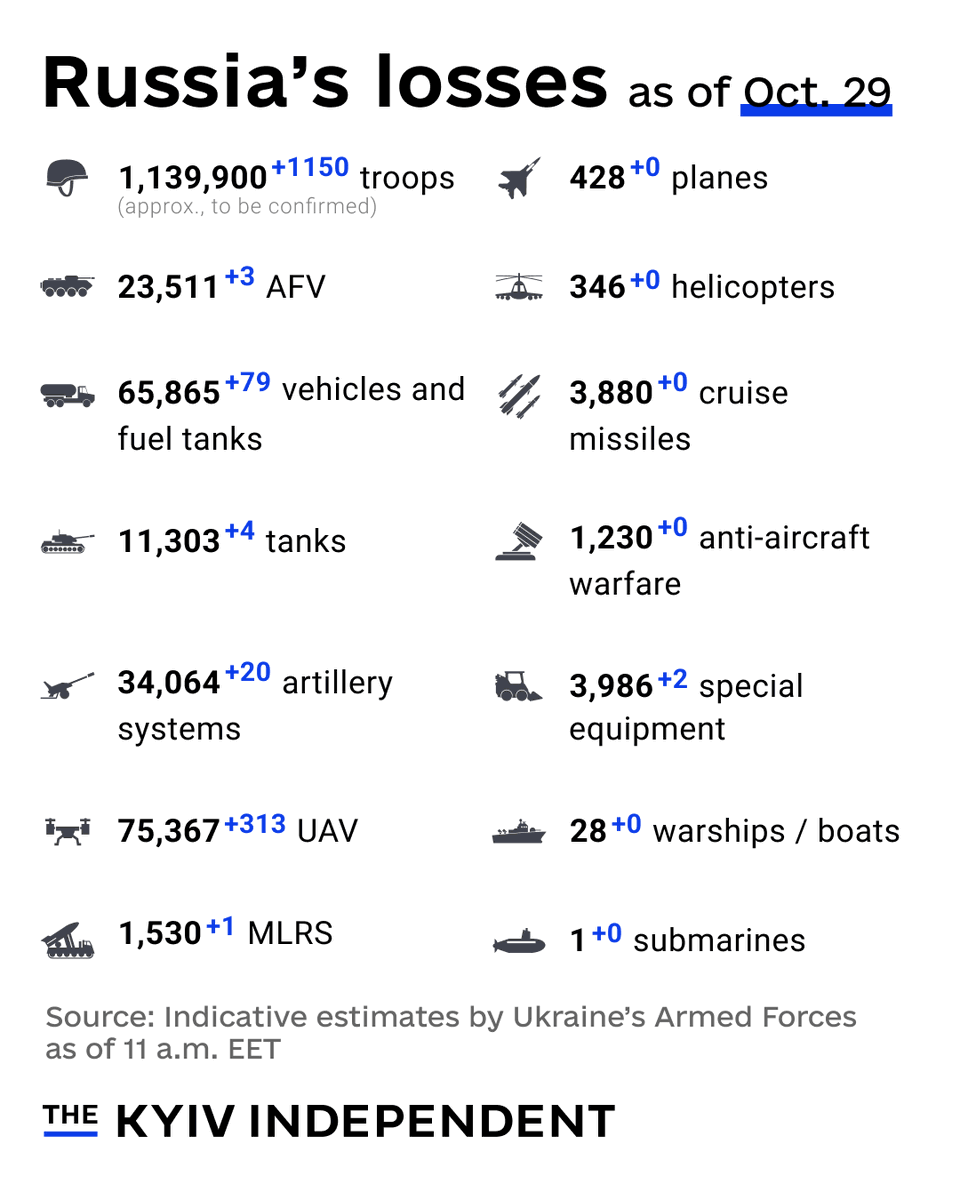

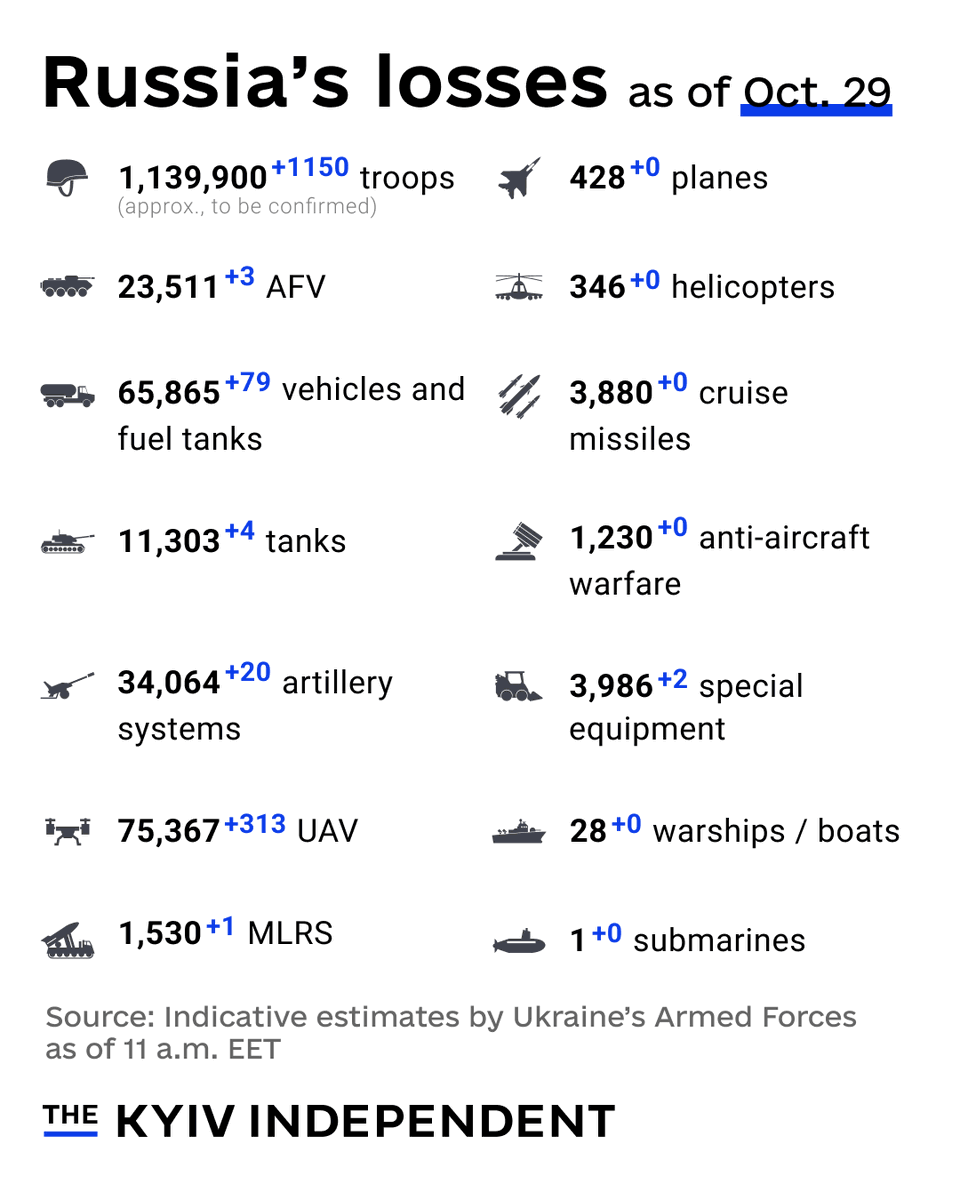

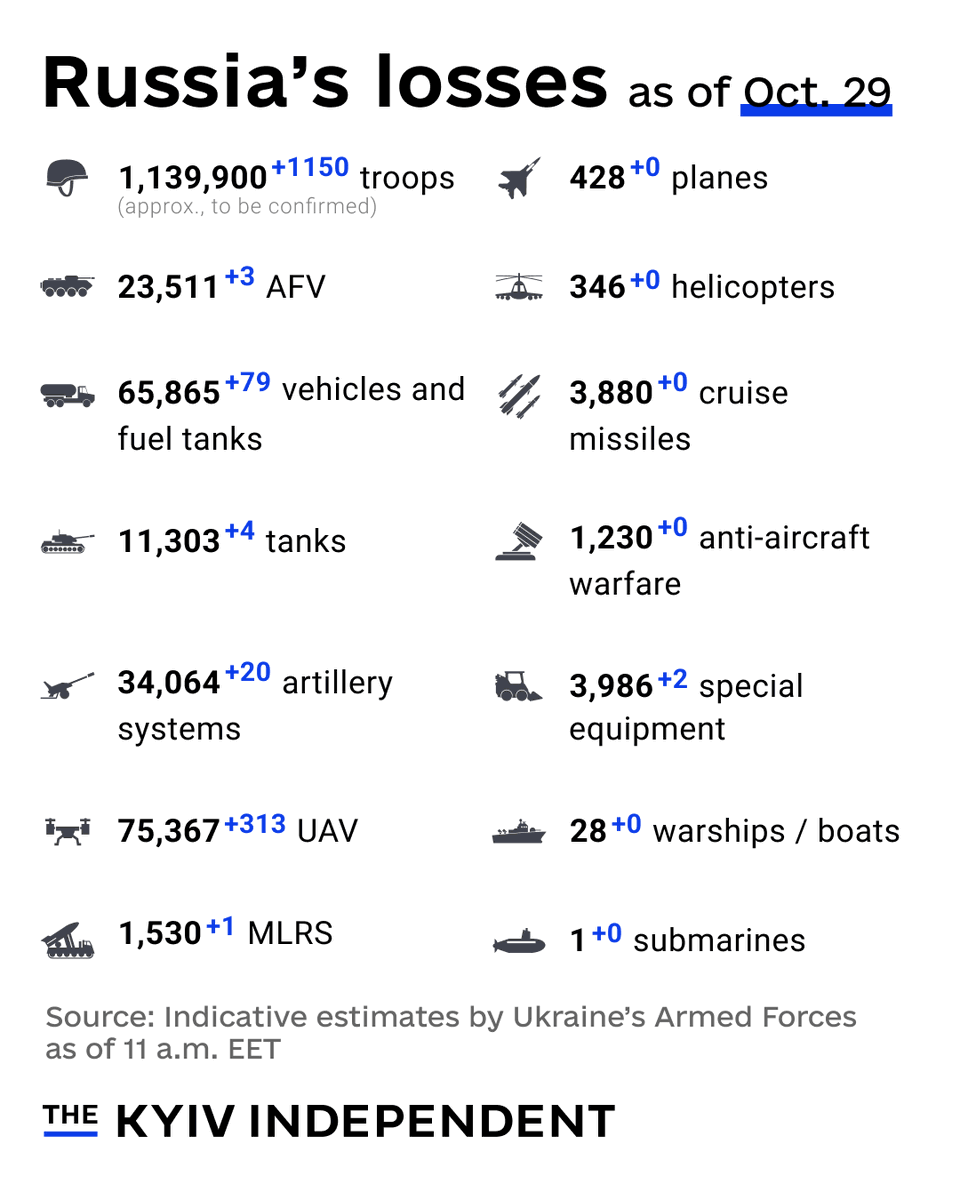

Day 1,341 of the Muscovian invasion. 1,150 [average is 849/day], i.e. more than 47 Russians, Norks and Cubans/h. Vehicles and fuel tanks more than 60% above average.

21,259

posted on

10/29/2025 12:32:18 AM PDT

by

AdmSmith

(GCTGATATGTCTATGATTACTCAT)

21,260

posted on

10/29/2025 12:37:07 AM PDT

by

AdmSmith

(GCTGATATGTCTATGATTACTCAT)

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first previous 1-20 ... 21,201-21,220, 21,221-21,240, 21,241-21,260, 21,261-21,276 next last

Disclaimer:

Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual

posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its

management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the

exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.

FreeRepublic.com is powered by software copyright 2000-2008 John Robinson