“Why do you dwell upon a statute law that was repealed 229 years ago?”

Like I said, you are so dumb.

How is it possible to be so dumb?

I refer to it for one reason, and one reason only. It DEFINES what a natural born citizen is in the Constitution.

The Naturalization Act of 1790 was not in effect all that long, I think.

But, it is valuable in that it DEFINES what a NATURAL BORN CITIZEN IS, a year after the Constitution was adopted.

That is why I refer to it. The definition of what a natural born citizen was what this thread was about, as far as I can remember. I don’t care what the Supreme Court says, what the Senate says, what some legal journalist says, it is what is meant by the writers of the Constitution and what was taught nationwide in all the schools for two centuries until Obama became president. I wonder why.

Like I said, you are so dumb. How is it possible to be so dumb?

You are sick. Seek help.

I refer to it for one reason, and one reason only. It DEFINES what a natural born citizen is in the Constitution.

I spoon fed you the entire 1790 Act from the Statutes at Large, the official source. I recommended quoting it and made that as simple as cut and paste. You couldn't do it. Why couldn't you quote the definition if it is there?

A child born in the United States, subject to its jurisdiction (subject to its laws), is born a citizen. The constitution so states without reference to the parents. It does not matter if the parents are two illegal aliens awaiting deportation. All that matters is the child. Was the child born within the territory of the United States? Was the child born subject to the jurisdiction of the United States? If so, the child was born a citizen. If the child was born outside the United States, then it becomes a matter of federal law. No foreign law is relevant.

What the Act of 1790 says provided for the dimwitted:

And the children of citizens of the United States, that may be born beyond sea, or out of the limits of the United States, shall be considered as natural born citizens:

What is the definition of natural born citizen — the children of citizens of the United States, that may be born beyond sea? Are you a natural born idiot?

Assume arguendo it said "shall be considered as a horse." Would that provide a definition of a horse?

There is no definition of natural born citizen in the Act of 1790. There is an example of one who shall be considered as a natural born citizen if born overseas and conforming to certain requirements of the effective act. That Act has changed multiple times, and the specified requirements have changed repeatedly.

The 1790 Act no more defines natural born citizen than does the Constitution. The Constitution was written in the language of the English common law. English common law used the term natural born subject. In the very early days of the American republic, the terms natural born subject and natural born citizen were used interchangeably. What was meant by natural born citizen was clear enough until 2008.

The folks who wrote the 1790 Act repealed it in 1795. It is as effective as the 18th Amendment.

Let us try the Act of 1802:

Sec. 4. And be it further enacted, That the children of persons duly naturalized under any of the laws of the United States, or who, previous to the passing of any law on that subject, by the government of the United States, may have become citizens of any one of the said states, under the laws thereof, being under the age of twenty-one years, at the time of their parents being so naturalized or admitted to the rights of citizenship, shall, if dwelling in the United States, be considered as citizens of the United States, and the children of persons who now are, or have been citizens of the United States, shall, though born out of the limits and jurisdiction of the United States, be considered as citizens of the United States: provided, that the right of citizenship shall not descend to persons whose fathers have never resided within the United States: Provided also, that no person heretofore proscribed by any state, or who has been legally convicted of having joined the army of Great Britain, during the late war, shall be admitted a citizen, as aforesaid, without the consent of the legislature of the state in which such person was proscribed . SEC. 5. And be it further enacted, That all acts heretofore passed respecting naturalization, be, and the same are hereby repealed.

APPROVED, April 14, 1802.

And so, as of April 14, 1802, persons born overseas were considered citizens only if born of parents who were citizens on or before April 14, 1802. This was noted in a paper by Horace Binney in The American Law Register in February 1854. By that time it would seem the parents had to be near seventy years old at the time of birth, or in other words, no children born overseas were becoming citizens of the United States pursuant to the 1802 law in effect. It mattered not what they intended in 1802.

Binney:

It does not, probably, occur to the American families who are visiting Europe in great numbers, and remaining there, frequently, for a year or more, that all their children born in a foreign country are Aliens, and when they return home, will return under all the disabilities of aliens. Yet this is indisputably the case; for it is not worth while to consider the only exception to this rule that exists under the laws of the United States, viz., the case of a child so born, whose parents were citizens of the United States, on or before the 14th of April, 1802. It has been thought expedient, therefore, to call the attention of the public to this state of the laws of the United States, that if there are not some better political reasons for permitting the law so to remain, than the writer is able to imagine, the subject may be noticed in Congress, and a remedy provided.

Chancellor Kent, in adverting to this peculiarity of our laws, in the fourth part of his Commentaries on American Law, holds out, it is true, to the children so born, the possible “resort for aid, to the dormant and doubtful principles of the common law;” for he remarks: “it is said that in every case, the children born abroad, of English parents, were capable, at common law, of inheriting as natives, if the father went abroad in the character of an Englishman, and with the approbation of his Sovereign;” and he cites three authorities for this dicitur which will be considered presently; but it is clear, from the Chancellor’s context, that he placed little reliance upon this alleged doctrine of the common law; and it can be shown that it was not worthy of the least. There is no reasonable doubt existing at this time, nor has there been in England, for nearly four hundred years, that the common law acknowledges no such principle, but, to use Lord Kenyon’s language in Doe vs. Jones, 4 Dumford and East, 308, that “the character of a natural-born subject, anterior to any of the statutes, was incidental to birth only. Whatever were the situations of his parents, the being born within the allegiance of the King, constituted a natural-born subject;” and consequently, anterior to any of the statutes, the being born out of the allegiance of the king, constituted an alien.

- - - - -

The definition of what a natural born citizen was what this thread was about, as far as I can remember. I don’t care what the Supreme Court says, what the Senate says, what some legal journalist says, it is what is meant by the writers of the Constitution and what was taught nationwide in all the schools for two centuries until Obama became president.

And you know this from your experience in grade skool for the gifted for two centuries.

Chester Arthur became Vice President, and later President in 1881. Chester Arthur was born in 1829. His father was naturalized in 1842. Numerous candidates had foreign parents. The nitwits did not come out of the closet until 2008.

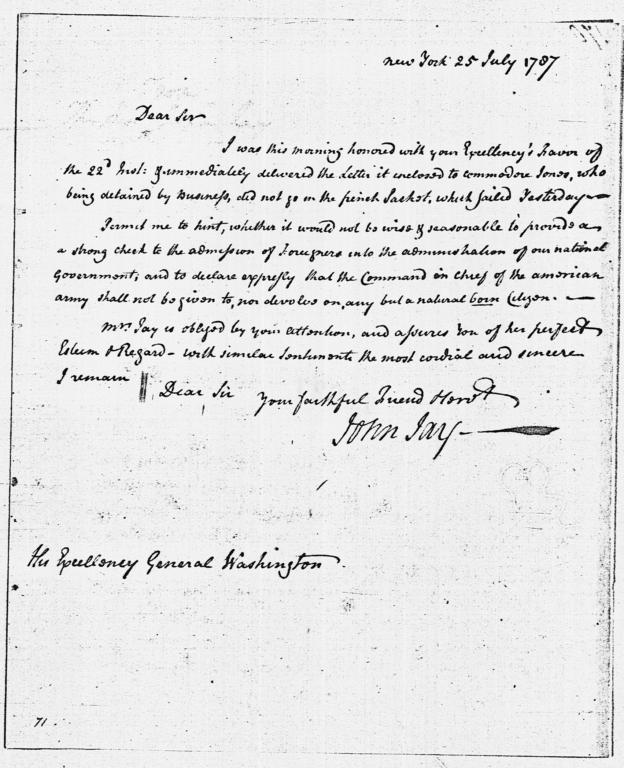

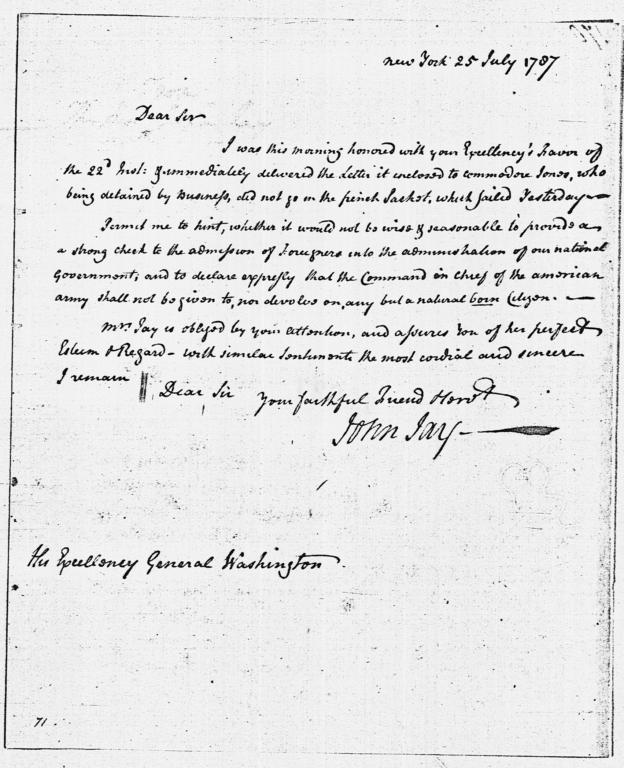

To get nearer than 1790, we can go right to John Jay and George Washington at the time of the Constitutional Convention, 25 July 1787.

Say it along with John Jay. A "natural born citizen." Say it to yourself over and over, and stress the word born. Eventually it will sink in.

I don’t care what the Supreme Court says, what the Senate says, what some legal journalist says, it is what is meant by the writers of the Constitution....

I see you do not know the first thing about law. You are about as ignorant of the topic as someone can get.

Conroy v. Aniskoff, 507 US 511, 519 (1993), Scalia, J., concurring

The greatest defect of legislative history is its illegitimacy. We are governed by laws, not by the intentions of legislators. As the Court said in 1844: "The law as it passed is the will of the majority of both houses, and the only mode in which that will is spoken is in the act itself...." Aldridge v. Williams, 3 How. 9, 24 (emphasis added). But not the least of the defects of legislative history is its indeterminacy. If one were to search for an interpretive technique that, on the whole, was more likely to confuse than to clarify, one could hardly find a more promising candidate than legislative history. And the present case nicely proves that point.

Judge Harold Leventhal used to describe the use of legislative history as the equivalent of entering a crowded cocktail party and looking over the heads of the guests for one's friends.

The purported intent of the lawgiver is irrelevant if the actual words of the law have a clear meaning. The words prevail even where the lawgiver's words are contrary to his intent. This is even so with legislation where the legislators voted to pass legislation. The words are ratified or passed into law, the intent is not.

Ex Parte Grossman, 267 U.S. 86, 108-09 (1925)

The language of the Constitution cannot be interpreted safely except by reference to the common law and to British institutions as they were when the instrument was framed and adopted. The statesmen and lawyers of the Convention who submitted it to the ratification of the Conventions of the thirteen States, were born and brought up in the atmosphere of the common law, and thought and spoke in its vocabulary. They were familiar with other forms of government, recent and ancient, and indicated in their discussions earnest study and consideration of many of them, but when they came to put their conclusions into the form of fundamental law in a compact draft, they expressed them in terms of the common law, confident that they could be shortly and easily understood.

"A Matter of Interpretation," Federal Courts and the Law, by Antonin Scalia, 1997. This book contains an essay by Antonin Scalia and responses to that essay by professors Ronald Dworkin, Mary Ann Glendon, Laurence Tribe, and Gordon Wood. There is a final response by Antonin Scalia.

Laurence Tribe, pp. 65-6

Let me begin with my principal area of agreement with Justice Scalia. Like him, I believe that when we ask what a legal text means — what it requires of us, what it permits us to do, and what it forbids — we ought not to be inquiring (except perhaps very peripherally) into the ideas, intentions, or expectations subjectively held by whatever particular persons were, as a historical matter, involved in drafting, promulgating, or ratifying the text in question. To be sure, those matters, when reliably ascertainable, might shed some light on otherwise ambiguous or perplexing words or phrases - by pointing us, as readers, toward the linguistic frame of reference within which the people to whom those words or phrases were addressed would have "translated" and thus understood them. But such thoughts and beliefs can never substitute for what was in fact enacted as law. Like Justice Scalia, I never cease to be amazed by the arguments of judges, lawyers, or others who proceed as though legal texts were little more than interesting documentary evidence of what some lawgiver had in mind. And, like the justice, I find little to commend the proposition that anyone ought, in any circumstances I can imagine, to feel legally bound to obey another's mere wish or thought, or legally bound to act in accord with another's mere hope or fear.

Aldridge v. Williams, 44 U.S. 9, 24 (1845)

In expounding this law, the judgment of the Court cannot in any degree be influenced by the construction placed upon it by individual members of Congress in the debate which took place on its passage nor by the motives or reasons assigned by them for supporting or opposing amendments that were offered. The law as it passed is the will of the majority of both houses, and the only mode in which that will is spoken is in the act itself, and we must gather their intention from the language there used, comparing it, when any ambiguity exists, with the laws upon the same subject and looking, if necessary, to the public history of the times in which it was passed.

United States v Union Pacific Railroad Company, 91 U.S. 72 (1875)

In construing an act of Congress, we are not at liberty to recur to the views of individual members in debate nor to consider the motives which influenced them to vote for or against its passage. The act itself speaks the will of Congress, and this is to be ascertained from the language used. But courts, in construing a statute, may with propriety recur to the history of the times when it was passed, and this is frequently necessary in order to ascertain the reason as well as the meaning of particular provisions in it. Aldridge v. Williams, 3 How. 24; Preston v. Browder, 1 Wheat. 115, 120 [argument of counsel -- omitted].

Downes v. Bidwell, 182 U.S. 244, 254 (1901)

In expounding this law, the judgment of the Court cannot in any degree be influenced by the construction placed upon it by individual members of Congress in the debate which took place on its passage nor by the motives or reasons assigned by them for supporting or opposing amendments that were offered. The law as it passed is the will of the majority of both houses, and the only mode in which that will is spoken is in the act itself, and we must gather their intention from the language there used, comparing it, when any ambiguity exists, with the laws upon the same subject and looking, if necessary, to the public history of the times in which it was passed.

Wong Kim Ark at 169 U.S. 658-59:

It thus clearly appears that, by the law of England for the last three centuries, beginning before the settlement of this country and continuing to the present day, aliens, while residing in the dominions possessed by the Crown of England, were within the allegiance, the obedience, the faith or loyalty, the protection, the power, the jurisdiction of the English Sovereign, and therefore every child born in England of alien parents was a natural-born subject unless the child of an ambassador or other diplomatic agent of a foreign State or of an alien enemy in hostile occupation of the place where the child was born. III. The same rule was in force in all the English Colonies upon this continent down to the time of the Declaration of Independence, and in the United States afterwards, and continued to prevail under the Constitution as originally established. In the early case of The Charming Betsy, (1804) it appears to have been assumed by this court that all persons born in the United States were citizens of the United States, Chief Justice Marshall saying: "Whether a person born within the United States, or becoming a citizen according to the established laws of the country, can divest himself absolutely of that character otherwise than in such manner as may be prescribed by law is a question which it is not necessary at present to decide." 6 U. S. 2 Cranch 64, 6 U. S. 119.

In Inglis v. Sailors' Snug Harbor (1833), 3 Pet. 99, in which the plaintiff was born in the city of New York about the time of the Declaration of Independence, the justices of this court (while differing in opinion upon other points) all agreed that the law of England as to citizenship by birth was the law of the English Colonies in America. Mr. Justice Thompson, speaking for the majority of the court, said: "It is universally admitted, both in the English courts and in those of our own country, that all persons born within the Colonies of North America, whilst subject to the Crown of Great Britain, are natural-born British subjects."

Wong Kim Ark at 169 U.S. 662-63:

In United States v. Rhodes (1866), Mr. Justice Swayne, sitting in the Circuit Court, said: "All persons born in the allegiance of the King are natural-born subjects, and all persons born in the allegiance of the United States are natural-born citizens. Birth and allegiance go together. Such is the rule of the common law, and it is the common law of this country, as well as of England. . . . We find no warrant for the opinion that this great principle of the common law has ever been changed in the United States. It has always obtained here with the same vigor, and subject only to the same exceptions, since as before the Revolution."

The principle of English common law regarding citizenship carried on for three centuries before independence, and it continued after independence, with all thirteen original states explicitly adopting so much of the English common law as was not inconsistent with the Constitution, either in their state constitution or state statute law.

The law is not determined by wingnuts on the internet.