Posted on 10/12/2014 3:22:48 PM PDT by Heart-Rest

We do not recall these instances of anti-Catholicism to foster more animosity or violence, but recall them as part of our history, a history that, like so many others, included the targeting of ethnic and religious groups for persecution.

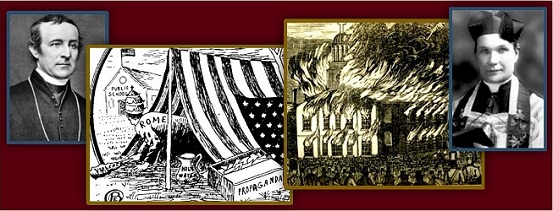

From left to right—Bishop John Hughes, New York, 1844; cartoon from Anti-Catholic book published by the Ku Klux Klan, 1926; Burning of St. Augustine Church, Philadelphia, 1844; Fr. James Coyle, Birmingham Alabama, murdered, 1921.

You have, no doubt, heard the children’s rhyme: “Sticks and stones may break my bones / But names will never hurt me.” That is not exactly true. For in the history of the Church in America, Catholics have been wounded by both physical violence and hate speech. This article will examine episodes of violence against American Catholics, considering the sticks and stones, the broken bones, and the words that encouraged such violence.

If the presence of anti-Catholic violence in American history is unknown to many, it is for good reason. We as Catholics do not usually like to talk about being a minority; we do not like to talk about persecution. For generations, our immigrant ancestors and their descendants fought to be considered “100% American,” not “hyphenated” Americans: Irish-American, German-American, Polish-American, or Italian-American. We Catholics have spent decades trying to assimilate into “White, Anglo Saxon, Protestant” (“WASP”) America and have, consequently, downplayed our distinctiveness. We wanted to fit in, and to achieve the American dream—to get good jobs, get a college education, and move to the suburbs.

In considering some episodes of anti-Catholicism, it should be noted that not all violence against Catholics was motivated exclusively by religion. In many cases, religious misunderstanding blended with nativism, and xenophobia, to bring about a toxic reaction to the United States’ Catholic newcomers. Consequently, anti-Catholic groups—that included the Know-Nothing party, the American Protective Association, and the Ku Klux Klan—espoused a form of bigotry, both religious and racially/ethnically motivated.

It should also be acknowledged that most manifestations of anti-Catholicism have not been violent. Much of anti-Catholicism in this country from the 18th century to today was more or less implicit: Protestants considered Catholics “the other.” Protestants often didn’t have Catholic friends, they (and Catholics!) frowned on Catholic-Protestant marriages, and non-Catholics refused to hire or promote Catholic workers. Other times, anti-Catholicism was muted, but real; non-Catholics questioned whether Catholics were even Christians, calling the Church the “Whore of Babylon” (of Revelation 17), and considered the pope the “Anti-Christ,” or taught unequivocally that all Catholics go to hell.

Other times, anti-Catholicism was more overt. In colonial times, laws forbade Catholics from voting, becoming lawyers, and teachers. Catholics, even in Maryland, which had at first tolerated them, demanded a “double tax” on Catholic property; parents could even be fined for sending their children to Europe to be educated as Catholics. The propagation of anti-Catholic ideas manifested itself in various ways: in newspapers, books, and pamphlets, in sermons, in laws, in popular discussion and debate, and, occasionally, in violence and property destruction.

The examples of violence that follow are admittedly among the most pronounced and outrageous forms of anti-Catholicism, but we should not be led to believe that anti-Catholicism was only the experience of a few. As a corrective, it is important to remember that in the 19th century, Catholic-Protestant debates and discussions, often acrimonious, took center stage. They were on everyone’s mind. When the anti-Catholic novel, Maria Monk’s Awful Disclosure—supposedly written by a former nun, telling stories of affairs between priests and nuns, and the murder of the children they conceived—was published in 1836, it became a near overnight sensation. By the start of the Civil War, it had sold 300,000 copies. Historians of this era claim it was among the most widely distributed book in America prior to the publication of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the popular anti-slavery book.

Anti-Catholic violence has taken the form of protest against Catholics who were taking their place in the public square. Catholics, it was feared, could subvert the American Republic, especially its democratic processes, and its “public” schools. When Franciscan priests and brothers first came to Cincinnati, Ohio, from Austria in 1844, onlookers did not know what to think of them, walking through the streets in their brown habits. But some recognized them immediately as “Catholic monks,” potential anti-American subversives. In his journal, one of the first Franciscans in Cincinnati, Fr. William Unterthiner, described the animosity directed at Catholics, especially priests, in mid-1840s Cincinnati:

The Protestants here are even worse (than in other places in the U.S.); so goes the protest. Today … some people threw wooden sticks at us, and cursed us (as we walked down the street). It is certainly true that a person is free to choose one, or even no religion, but one would still be very mistaken if he believed that Catholics are allowed to live unhindered.

As Catholic immigration increased throughout the 1840s and 1850s, concern mounted that Catholics were taking over America’s public schools—an attempt that would eliminate the Bible (particularly the King James version) from everyday classroom use. The challenge offered by Catholics to “public” schools, that were de facto Protestant schools, brought Catholics and Protestants into frequent conflict.

The so-called “Eliot School Rebellion,” which occurred in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1859, proves a dramatic example. The state law that required the Ten Commandments to be recited (always using the King James Bible) in every classroom every morning, pitted Catholics, who viewed non-Catholics’ Bibles as false translations, against Protestant teachers, parents, and schoolmates. Ten-year-old Thomas Whall, a Catholic, was asked to take his turn leading the recitation of the Ten Commandments. When Whall refused because of his Catholic faith (and his desire to only read from the Douay-Rheims translation, an approved Catholic translation), he was disciplined. Whall had been urged by his parish priest not to recite Protestant prayers, nor read from the King James Bible.

A few days later, when Whall refused again, his teacher struck him with a rattan stick for half an hour until he was bleeding; he refused to give in, and his fellow Catholic classmates cheered him on. The school’s principal demanded that Catholic children, who refused to recite the commandments, leave the school; hundreds left in protest. The “rebellion” helped extend the parochial school system in Massachusetts. Within a year, a Catholic school was established in Whall’s parish with an enrollment of over 1,000.

Not all anti-Catholic violence was physical. Sometimes it resulted in the destruction of property. These episodes represent the ferocity of anti-Catholic violence, though without physical assault or loss of life.

In 1834, an anti-Catholic mob burned the Ursuline Convent in Charlestown, near Boston. The convent school there educated primarily upper-class Protestant girls, and worries of the Protestant elites’ attraction to Catholicism festered. This, together with the rumor of an Ursuline sister being held in the convent against her will, and the anti-Catholic preaching of Rev. Lyman Beecher, father of Harriet Beecher Stowe, incited a riot.

An angry mob gathered outside the convent, calling for the release of the sister, but the Ursuline mother superior threatened the crowd: “The Bishop has 20,000 of the vilest Irishmen at his command, and you may read your riot act till your throats are sore, but you’ll not quell them.” The crowd broke down doors and windows to enter the convent, and began to ransack the buildings. The sisters and their students rushed out the back of the convent, and hid in the garden. At about midnight, the rioters set fire to the building, burning it to the ground. Of the 13 men arrested and charged with arson, all but one was acquitted. The governor pardoned him in response to a petition signed by 5,000 Bostonians. Distrust of sisters in convents led eventually to a number of state legislatures proposing “convent inspection laws,” authorizing the warrantless searches of Catholic buildings—convents, monasteries, rectories, and churches—for weaponry, and for young women supposedly seduced into the convent and held against their will.

In 1844, two Catholic churches were burned in Philadelphia after it was rumored Catholics were insisting on the removal of the Bible from public schools. The same scene might have been repeated in New York City, but New York’s Bishop, John Hughes, warned: “If a single Catholic church is burned in New York, the city would become a second Moscow,” a reference to the 1812 burning of Moscow in which its own citizens set fire to the city as Napoleon’s soldiers closed in.

In 1854, as the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., was being constructed, nine men, associated with the anti-Catholic Know-Nothing party, sneaked up to the base of the monument to steal a stone that had been engraved “Rome to America.” The stone, which was to have been placed inside the monument, along with other stones given as gifts from foreign governments, had been shipped from the Vatican. The men carried the stone to a boat waiting at the tidal basin, smashed it into pieces, and dumped it in the middle of the Potomac River. For them, the stone indicated the threat of the Catholic Church’s takeover of the U.S. government, a much talked about, but very unlikely, threat. The identity of the conspirators was shrouded in mystery; no one was ever convicted of the crime. In 1982, a replica of the stone, given by a priest from Spokane, Washington, was installed in the monument by the National Park Service.

The attack on the Shrine of Our Lady of Juan del Valle in San Juan, Texas, provides a final, modern example. In 1970, a non-denominational preacher intentionally flew a small airplane into the church while Mass was being celebrated. No one was injured except the kamikaze pilot who died. While the overall property loss was estimated at $1.5 million, many believed it a miracle that no one else was hurt or died in the tragedy. A new shrine was dedicated in 1980 where the previous church had stood.

Infrequently, physical violence and death were the consequence of anti-Catholicism. In 1853, Pope Pius IX sent Archbishop Gaetano Bedini to visit the U.S. and report back to him on the state of the Catholic Church in America. Because many U.S. Protestants viewed the pope as sinister, and as an enemy of freedom, they blamed his representative.

In Cincinnati, hundreds of protesters marched towards the cathedral where Bedini was staying, carrying signs, a scaffold, and an effigy of the archbishop. The signs read “Down with Bedini!”; “No Priests, No Kings”; and “Down with the Papacy!” Fearing an attack on the residence, the police attempted to turn back the demonstrators. In the ensuing melee, one protester was killed, 15 were wounded, and 63 were arrested. Most of the city’s residents supported the protesters, blaming the police for exercising brutality. Those who had been arrested were released, the charges were dropped, and an investigation of the police commenced. As Bedini continued to tour the country, violent disturbances erupted in Cleveland, Louisville, Baltimore, Boston, and New York. Fearing further violence in New York, Bedini was secretly transported by way of a rowboat to the steamship on which he would depart for Europe.

Not long after Bedini returned to Italy, anti-Catholic mob violence struck Louisville, Kentucky. In an incident known as “Bloody Monday” (August 6, 1855), concern about Catholic influence over the electoral process contributed to a mob attack on Irish Catholic neighborhoods, resulting in 22 deaths, scores of injuries, and widespread property destruction. Five people were later indicted; none was convicted.

Religious and racial prejudice combined in the deep South, resulting in the murder of a priest in 1921. Father James Coyle, priest of Birmingham, Alabama, was shot and killed on his rectory front porch. Coyle had performed the wedding of a recent convert to Catholicism, the daughter of a Methodist minister and Ku Klux Klan member, to a Puerto Rican Catholic man. The Methodist minister’s daughter had become interested in Catholicism as a young girl; she converted at age 18 and was received into the Catholic faith by Father Coyle. Only a few months later, Coyle witnessed the girl’s marriage. When her father found out about the clandestine wedding, he confronted Coyle and shot him. The minister was charged with the priest’s murder, but was acquitted by a jury who found him not guilty by reason of insanity. In 2012, Bishop William H. Willimon of the United Methodist Church presided over a service of reconciliation and forgiveness in Birmingham, asking for forgiveness for the role his church had played in the death of Father Coyle.

In recent years the threat of anti-Catholic violence has surrounded fidelity to the Church’s teaching on marriage and family life. In 2002, Mary Stachowicz, the parish secretary of now Bishop, Thomas Paprocki of Springfield, Illinois, was raped and murdered. Her killer stated to police that he attacked Stachowicz after she confronted him about his gay lifestyle. Bishop Paprocki, in public addresses on the Church’s approach to same sex attraction, relates the story of his former secretary’s murder in order to condemn all forms of violence based on bigotry. He feels compelled to speak about this form of anti-Catholic violence because it has been almost completely ignored by the media. Bishop Paprocki notes:

A Google search on the Internet for the name “Matthew Shepard” at one time produced 11.9 million results. Matthew Shepard was a 21-year-old college student who was savagely beaten to death in 1998 in Wyoming. His murder has been called a hate crime because Shepard was gay. A similar search on the Internet for the name “Mary Stachowicz” yielded 26,800 results.

Mary Stachowicz was also brutally murdered, also the victim of a hate crime, yet, her death went unnoticed. Perhaps, this is a signal that, as in the past, various forms of anti-Catholic violence are still viewed by some as acceptable, or at least, not worthy of notice.

Why examine these episodes of hate? Why not let them remain hidden in scarcely-read tomes of Catholic history? We do not recall these instances of anti-Catholicism to foster more animosity or violence, but recall them as part of our history, a history that, like so many others, included the targeting of ethnic and religious groups for persecution. Though the Church is often seen in overblown narratives as a perpetrator of violence, responsible for the horrors of the Crusades, the Spanish Inquisition, and the Holocaust, the Church has also been afflicted by violence motivated by religion. If history teaches us anything, it is that the memory of the past is so often selective.

Yet, this discussion should not end by recalling the role of religious belief in contributing to violence, but should remember the role of religious faith in promoting love. Fundamental to the Church’s teaching is the importance of humanity’s dignity as sons and daughters of the Creator. Violence, if even partly motivated by religion, contradicts what St. John taught us about God—“God is love” (1 Jn 4:8, 16)—a divine love that humanity is called to mirror and extend.

Yeah, I'll bet they do.

=============================================================

I know that many people do not refer to Mormons as Protestants, but some do (such as this person):

(I probably should have put the term "Mormon" there for Harry Reid instead of "Protestant" though.)

They weren't yet here in sufficient number to gin up a pogrom. Now, Continental Europe, that's another matter entirely.

Tell me, did Protestants invent the practice of burning witches at the stake? Oh, they didn't? Where on earth did they pick up such an ugly practice then, I wonder?

I’m a convert, and I’d be rich if I had a dollar for every time I’ve heard a Protestant talk about the whore of Babylon, and the book of Daniel, and the seven trumpets, and on and on. That’s what sola scriptura does for you. It makes you bat crazy. I’m glad we have the Magisterium.

“Tell me, did Protestants invent the practice of burning witches at the stake?”

Well it dates back to Germany and the Nordic countries. Bet you could go back older than that. However the protestants profected it during the witch trials. About 200,000 people were murdered. None I bet were witches, if there were any I know they were laughing at all that.

LOL ya think?

Protestants burned 1 or 2 people in Europe, too. I don’t know who invented it, and I don’t think you do either.

“That’s what sola scriptura does for you. It makes you bat crazy.”

No dear, that’s what being a protestant does for you, makes you bat crazy.

Most scholars peg the total number at 40,000 at the hands of both Catholic and Protestant, over the course of the entire “witch hunt” era spanning Europe and North America. The practice goes back in the Roman Catholic Church at least to persecution of the Knights Templar, who were accused of satanism, sodomy and malevolent sorcery, then burned at the stake. That was 13th - 14th century. The only remotely Protestant sect from that era would have been the Waldenses, who were not burning anyone at the stake. If there was such a thing associated with them, they were the ones burning.

It’s an ugly practice that was and is wrong. Do not try to pin it on Protestants for partisan advantage, however, because it will not work. Too many people know better.

Statistics from where? You make a sweeping statement that belies the true nature and extent of Roman Catholic clergy, by making a ridiculous claim which defies logic.

Roman Catholic churches carry no liability insurance. they "self-insure". that is why people that sue for sexual molestation get awards from the church.

Also, your claim is not backed by complete truth. Statistics can be manipulated just as we see with our current gum't claims about nearly everything (unemployment is now less than 6%, etc).

...There have been several efforts to document the Catholic abuse problem in the past two years, and next Friday the National Review Board, a lay watchdog panel, will release an accounting that it has overseen. CNN reported from a draft text that 4,450 priests were accused since 1950, about 4 percent of those serving in that era.

There have been few such efforts by Protestants. One is www.reformation.com, a Web listing of 838 allegations of clergy abuse, the oldest from 1933, in media in English-speaking countries (with 100 more waiting to be posted).

The categories: 251 in evangelical or fundamentalist "Bible churches," 147 Baptist, 140 Episcopal and Anglican, 46 Methodist, 38 Lutheran, 19 Presbyterian, and 197 others.

Since there are roughly 500,000 U.S. Protestant clergy - 11 times the Catholic total - that international total might indicate Catholicism has the bigger problem. ...

As to the title theme:

Sticks, Stones, and Broken Bones: The History of Anti-Catholic Violence in the U.S.

=============================================================

On the other hand, did you read the link I put in post #102? That guy is a Mormon writer who ran for congress, and he believes Mormons should be called Protestants (see that 102 link).

Here's that guys facebook:

I said it started in Germany around the Nordic times. Probably older.

Not that you people ever really pay attention.

Oh really? Was it another example of syncretism then, of the Roman Catholic Church picking up pagan habits and incorporating them?

Why would a church centered upon Rome be mimicking Nordic pagans otherwise, and who thought it was a good idea? When did this so-called Nordic era end, and when was the first burning at the stake at the hands of Roman Catholic authorities? Was there any overlap?

I bow to your expertise upon this matter, and look forward to your reply, particularly the timeline to which you refer. That should be fascinating.

Nkp, I’ll have to trust you on our neck of the woods, but in my part absolutely not true.

Catholics don’t deny the Bible, but they have a profound awareness that words can be manipulated to suit the manipulator.

And I realize that may be over doing it but can not understand the Catholics ignoring a scripture that is so plain.

Protestantism isn’t far from Islam in that sense.

I don’t recall Catholics burning anybody at the stake in America, either.>>>>>>

I don`t know enough about Islam to comment on that.

But have read article after article of the thousands of people beheaded or killed in other ways by the Church for no other reason than they would not convert.

I do not believe every thing I read but it is something to put in the balances.

I believe what I read in scripture that I understand, if I do not understand it I will ask and if I get a sensible answer fine, if not I will be content not knowing.

Catholics don’t deny the Bible, but they have a profound awareness that words can be manipulated to suit the manipulator.

And I realize that may be over doing it but can not understand the Catholics ignoring a scripture that is so plain.

Protestantism isn’t far from Islam in that sense.

I don’t recall Catholics burning anybody at the stake in America, either.>>>>>>

I don`t know enough about Islam to comment on that.

But have read article after article of the thousands of people beheaded or killed in other ways by the Church for no other reason than they would not convert.

I do not believe every thing I read but it is something to put in the balances.

I believe what I read in scripture that I understand, if I do not understand it I will ask and if I get a sensible answer fine, if not I will be content not knowing.

The nordic probably picked it up from somewhere else. Everyone copied everyone else in those days. Plus you assume it was a pagan ritual. The Nordics had their way of dealing with criminals, as did all societies. The Jews stoned people, Rome put people on a cross, the Noridics burned you. Rule of thumb when in a strange land don’t break the law.

I’m thinking it pre-dates the Catholic Church. Probably Neolithic man was doing it. Remember the story of 3 men in the fiery furnace. I’m not sure it’s even European.

Very good. Now can we dispense with the myth of Protestants somehow being uniquely responsible for burning witches? They weren’t.

The Spanish Inquisition by Jean Dumont

The following essay is taken the works of Jean Dumont, a professor of history at the Sorbonne in Paris. It is one of several essays in his book L’Eglise au Risque de l’Histoire - the Church at Risk from History. It is, in my opinion, the best work on this complex subject available. The translation for which I am responsible was approved by the author. I have tried without success to get it published in this country. Because of its importance, I have taken the liberty of placing it on my web page.

www.the-pope.com/spaninqc.rtf

THE SPANISH INQUISITION

The Spanish Inquisition is a subject of passionate polemic born of national, confessional, and then ideological confrontation. History - the only trustworthy witness - has not been given the freedom to speak. So much is this the case that a response to this true witness is and has always been forbidden. The basis of Father Lallemand’s contention has been forgotten However, as modern day specialists have shown, there is no doubt but that in a number of spheres (in dealing with sorcerers, blasphemers, writers, etc.) the Spanish Inquisition showed itself much more moderate and understanding than the civil justices (parliaments, provosts, bailiffs) which usurped the powers of the Inquisition in other countries.

TREMENDOUS SHAME AND INDIGNATION

Misinformed by the anti-inquisitorial attitudes promulgated successively and in a cumulative manner by the Protestants, the “philosophers,” the revolutionaries, the anticlericals and the liberals, Catholics themselves feel an insuperable shame and indignation whenever they hear the words “Spanish inquisition” mentioned.

This is particularly true of French Catholics who have been subjected to additional anti-Spanish polemic, carried on since the sixteenth century by “politicized” Catholics allied with Protestant Huguenots against the League, and then by the pamphleteers who engaged Cardinal Richelieu in his struggle against the Spanish hegemony. All this is further reinforced, even in our own times, by the official “secular” education.

This “black legend,” as Pierre Chaunu has justly brought out, was only “a cynical tool of psychological warfare” up to the time of the Renaissance and the classical period. Yet it is the foundation on which all the usual presentations of the Spanish Inquisition are based.

AN INAPPROPRIATE AND SHOCKING APOLOGETIC

What is worse is the inappropriate and totally unacceptable effort of Catholics, who in their desire to exculpate the Church, place the principal responsibility for this [seeming] abomination on the Spanish throne. Thus for example, at the start of the 19th Century, Joseph de Maistre in his Letters to a Russian gentleman on the Spanish Inquisition claimed that “everything attributed to this tribunal that was harsh or odious, especially the death penalty, should be charged against the government...While on the other hand, clemency was a characteristic of the Church.”

The affirmation is both inexact and offensive. The Spanish Inquisition was clearly, as we shall see, both in its actions and its methods, much more an ecclesiastical than a governmental institution. The faithful should not seek to win the respect of anyone by passing the blame onto others.

How is it that Catholics do not see that imputing what they consider to be the evils of the Inquisition exclusively to the Spanish monarchs is an indefensible naivete; a naivete which leads their adversaries to laugh at them, for quite the opposite is the case.

The Spanish monarchs only established the Inquisition by implementing the Papal Bull Exigit sincerae devotioinis of 1478. And in 1496, after sixteen years of intense inquisitorial activity, independent since 1494 from all possibility of appealing to Rome, these Monarchs, namely Isabelle and Ferdinand, by the Papal Bull Si convenit promulgated in the consistory of December 2, 1496. were given the official and unprecedented title of “Catholic Kings” which has always been retained by them. And this was after Pope Sixtus IV in 1482 for Castile (Bull Apostolicae Sedis), and in 1483 for Aragon (brief Supplicari Nobis completed in 1486) had personally named the famous Tomas de Torquemada as Inquisitor and then as Inquisitor-general.

AT LAST, SOME HIGHLY BALANCED JUDGEMENTS

And how is it that Catholics, especially those who claim to be historians, have not drawn attention to the fact that the masters of modern historiography who by the nature of things should be the antagonistic to the Spanish Inquisition, currently venture to disseminate highly balanced judgments on the Spanish Inquisition?

Thus Fernand Braudel, a professor at the College of France, makes note of “the relatively small number of victims” of the Holy Office. In like manner, the Israeli specialist Leon Poliakov develops the same observation in more than ten pages of his History of Anti-Semitism. Again, Marcel Bataillon, also a professor at the College of France, notes that “The Spanish Inquisition is characterized less by its cruelty than by the power of the apparatus [...] at its command.”

Similarly the Enciclopedia judaica castellana (The Spanish Jewish Encyclopedia) states that “The Spanish Inquisition was, for its time, much less inhumane than she is described as being. She was animated by idealism.” Thus, the Lutheran authority Ernst Schafer, like the Israeli specialist Haim Beinar, tells us that a careful study of the inquisitorial process reveals that the inquisitors were far from acting as arbitrarily as is so often claimed.

Returning once again to Braudel, we find he contradicts the claim that the Spanish Inquisition was unpopular, and states that it democratically incarnated “the most profound desire of the masses.” All this is confirmed and elaborated on by Spanish-Jewish professor Americo Castro at Princeton who in addition does a great deal to destroy the accusation of anti-Jewish racism so often laid at the door of the Inquisition. “The Church State [The Inquisition] was [in Spain] a quasi revolutionary conquest realized by the masses who considered themselves wronged, and by the Conversos (Jewish converts) or their descendants, who were anxiously seeking to forget their origins.”

THE JUST GLORIES OF CATHOLICISM

How is it that Catholics do not realize that in condemning the Spanish Inquisition in absolute terms, they also condemn the Papacy and the Catholic Kings, along with all those who actively participated in this enterprise, individuals who are the true glory of Catholicism (another fact which has escaped their attention)?

Many of the Inquisitors, starting with the Inquisitor-generals Torquemada and Deza, belonged to the Dominican Order, the same Dominican order which was at the same time the champion, even going to extremes, along with Vitoria and Las Casas, of the rights of man. Another Inquisitor-general was Jimenez de Cisneros, the well known reformer and promoter of humanism, who belonged to the Franciscan order.

Again, they included Jesuits such as the great historian, political theoretician and economist Juan de Mariana. Beyond this there was a long line of equally well known bishops such as Alonso Manrique, the reformer and friend of Erasmus, and Bernardo de Sandoval, the patron of Cervantes, known for his inexhaustible charity. The Inquisition also produced two great Catholic play-writers, Lope de Vega, an “intimate” of the Holy Office, and the “Inquisitorial poet” Calderon of Barca, the only Catholic who can be considered an equal to Shakespeare, etc.

The time has come to dispel the lies and present a honest picture of the Spanish Inquisition; to provide the true history which has been suppressed for so long by the passions of polemic. As will become obvious, this portrait will be provided because of the opportunity that we have had to study the subject in depth, and above all by the large number of documents and books of the period that we have collected or discovered. These documents quietly destroy the view which has been so systematically deformed.

By means of them we will shed light on the aggregated silence of history.

A VERY LIBERAL TRADITION

The first characteristic of an authentic portrayal: the Inquisition was not a Spanish, or to be more precise, a Castilian tradition. During the Middle Ages, when the Inquisition was imposed throughout France, the Castilians were ignorant of its existence. They knew nothing about the pyres of the Albigensians or of the Templers - not even about that of St. Joan of Arc.

Tolerance and the ability to live together with others were so well established in Castile - which was not the less Christian for all that - that the epitaph of the Saint King Ferdinand (cousin of the French Saint Louis) in the Cathedral of Seville was drawn up in four languages, Latin, Castilian, Arabic and Hebrew.

The prejudicial belief in “Spanish fanaticism” flies in the face of well established historic patterns and facts up to the time that the Inquisition was established in Castile. So much is this the case that in a letter addressed by the Spanish Franciscans to their Jeromite compatriots asking for the establishment of the Inquisition in Castile, dated August 10, 1461, one reads: “It is unnecessary to establish an inquisition in the kingdom against the heretics such as was done in France and in so many other Christian realms and provinces.

Moreover, in mediaeval Spain, there was no racism on the part of the Christians against their very numerous Jewish compatriots which constituted perhaps as much as 10% of the population. “During the Middle Ages,” Americo Castro notes, “many illustrious Christian families mixed their blood with the families of Jews for financial reasons or because of the beauty of the Jewish woman; before the 15th century no one was scandalized by this.” As a result, there was no racism of a biological nature. Nor was there any racism based on religion.

There was in fact a continuous dialogue between the Christians and the Jews. Such is exemplified by the debate in Tortosa (1414) where the Christian argument triumphed and where thirty out of 40 rabbis that participated were converted of their own free will to Christianity, followed shortly thereafter by thousands of their co-religionists.

The product of this double rapprochement - both biological and religious - was the highly significant Spanish converso, that is to say Christians with Jewish blood who were soon to wield a power highly disproportionate to their number. The conversos tended to monopolize finance, the collection of taxes, medicine, municipal government, the courts, the Church (innumerable bishops were conversos), the police (Santa Hermandad) and the Orders of Chivalry. By means of intermarriage, they penetrated the nobility.

This was to such a degree true that the future King, Ferdinand the Catholic, was born of Jewish blood, his mother being one Henriquez. In a similar manner the intelligentsia, ministers, secretaries, and chroniclers of the Catholic Kings were born of Jewish blood; men such as Diego de Valera, Hernando de Talavera, Hernando del Pulgar, Miguel Perez de Almazan (the first secretary of State who was placed in charge of Inquisitorial affairs).

It is hardly necessary to point out that in no other Christian country did such a situation prevail; certainly not in France from which the Jews had been completely and definitely expelled in 1394 (they had been expelled from England in 1290).

A DRAMATIC DETERIORATION

In the face of such prevailing conditions in Spain, why was the Inquisition required; how could it have been established; and why was it primarily directed against the conversos of Jewish origin? Only because there was a deterioration in the ability of these groups to live together starting at the end of the XIVth century and progressively increasing to a critical point during the second half of the XVth century.

Because of the increase in converso power, the older established Christians everywhere felt themselves increasingly threatened, both with regard to their property and their identity. At first they reacted in a disorganized manner, but then in an increasingly systemic way, against Jews who fostered the increasing influence and domination of their brother conversos. In 1391 there was a bloody slaughter of Jews throughout much of Spain. This resulted in a significant increase in the number of conversos because many Jews sought safety in baptism - though now it was under constraint, or at least indirectly so.

During the following half century the incessant preaching of Saint Vincent Ferrar, who was certainly not anti-Semitic, resulted in another wave of conversions, often of inadequately catechized Spanish Jews. As a result, while the numbers increased, the conversos phenomena became more and more mixed. This was particularly true in the religious domain where certain Jewish customs were introduced into the heart of Spanish Christianity. They were seen as Judaizing.

Beyond this, as the converso historians themselves noted, as this heterogeneous group of converts became more and more powerful, they displayed an arrogance towards the older established Christians and even oppressed them. Thus the converso Alonso de Palencia in writing to his brothers in Cordova stated: “extraordinarily enriched by special trades, they have become increasingly proud and display an insolent arrogance, seeking to gain control of public offices, after which by bribery and against all the rules, they get themselves admitted to the chivalrous orders where they seek to form cliques (bandos).”

These cliques succeeded in forming a band of “three hundred well armed cavaliers” in Cordova. Secure in their impunity, the conversos of this city “became so audacious as to have no fear of celebrating Jewish ceremonies whenever they wished.” Another converso chronicler, Diego de Valera, future principal counselor of the Catholic Kings confirmed that “the new Christians oppress the old established ones in all sorts of ways.”

A BLOOD BATH

A violent reaction soon occurred. The older established Christians revolted savagely against the conversos. In 1449 they regained control of Toledo after a bitter struggle with the converso bandos who had been in power there as they had been in Cordova. And the victorious rebels promulgated the “statutes regarding the purity of blood lines” which only allowed the old established Christians access to positions of public authority. The same year, 1449, Ciudad-Real “liberated” itself along the same lines.

When in 1467 the conversos tried to regain their powers, the two cities initiated an orgy of killing and destruction. In 1468 the blood bath spread from Vieille-Castile to Sepulveda; and in 1473 to Andalusia. The fight against the conversos of Cordova, heavily armed as we have said, lasted for two whole days. When the old established Christians won, it was in the midst of immense destruction and many deaths. They then proceeded to regain control throughout the region and the routed conversos were killed by the peasants in the fields.

A generalized bloody pogrom spread throughout the vast territory of Almodovar del Campo south of la Mancha, to Cabra in the direction of Malaga. Soon Jaen was “liberated” in the same way that Cordova had been.

The following year, 1474, Vielle-Castile was involved in a new blood bath. Segovia, after a bitter struggle, was also won over by the old established Christians. But this time - most importantly - the blood bath occurred directly before the eyes of the Catholic Kings. When they entered the city the battle had just terminated. “There were still marks of fresh blood in the streets and on the walls of the houses. The city reeked from the number of slaughtered, the rotting carcasses and the destruction.” That very day the Catholic Kings came to a clear decision.

THE CRY FOR PUNISHING THE “CONVERSO

From this moment, in the face of the imprudent actions of their blood brothers and the brutality of the reactions of the older established Christians, the more prominent conversos, sincerely attached to their new faith, promulgated a detailed denunciation of the “judaising danger.” They further called for an institutional vigilance that was not arbitrary but regulated, which little by little took on the shape and character of an Inquisition.

For example, from the very start of the insurrection in Toledo, the Diaz de Toledo, the recorder of the court of royal justice, while fully respecting the rights of his converso brothers, declared: “If there is any new Christian convert who conducts himself badly, he should be punished and chastised severely. And I will be the first one to bring the wood to burn him, and to light the fire. I will go further and state that if he is of Jewish lineage, he should be more severely and more cruelly punished, because he should know what is involved better than others in so far as he has a knowledge of the Law and the Prophets.”

As one knows, the Law and the Prophets were quite rigorous with regard to prescriptions and punishments”

The aged Rabbi Solomon Halevi who became bishop of Burgos under the name of Pablo de Santa Maria, wrote a Dialogus contra Judaeos. Similarly, the ancient Rabbi Jehoshua Ha-Lorqui, who in religion took the name of Jeronimo de Santa Fe (Jerome of the Holy Faith) wrote an anti-Jewish pamphlet entitled Hebraeomastix. And the Aragonais converso Pedro de la Caballeria, wrote his Zelus Christi contra Judaeos.

Finally, and with more violence than the others, a Franciscan converso, Alonso de Espina, wrote in his Fortalitium fidei (1459): “I believe that if there was a real Inquisition in these days, a great many would be thrown into the fire, which would include all those who were found to be Judaizers.”

Thus as Henry Kamen noted: “It is a fact that the principle anti -Jewish polemicists were the ex-Jews.” And that the fearful term “Inquisition” was used by them in the precise sense that is attached to this word.

THE WAY THINGS STARTED AND THE REACTION

Now, as we have seen, the Catholic Kings - Ferdinand was of converso blood - who were surrounded by conversos such as their chief of state Hernando de Talavera took a position similar to that of the relator Diaz de Toledo.

Now what happened is that the kings rapidly found for the conversos, their only possible alternative in the face of the bloody repression initiated by the old established Christians. As the Israeli historian Cecil Roth noted: “In comparison to the killing of the Jews that occurred in 1391, there was a great difference. At that time those who had been attacked could save themselves by accepting baptism. Now they no longer had this alternative.”

The only solution was a new baptism dispensed and attested to by an authority which the old established Christians would not dare to contradict. In face of the general massacres which progressively spread from one place to another in the provinces of the kingdom of Castile, the rigor of the “new baptism” took its justification or its pretext, or at least its strength, from the fact that it could not be disputed. For none of the old established Christians would dare to inveigh against a Tribunal of the faith founded by a Pope and established by the full force of the royal power. Once the organization was in place, its power and its strictness practically and morally defused the obsession of the old Christians.

All the conversos “qualified” by the Tribunal of the faith, were protected by being certified as Christians and Spaniards with full legal rights. Repression was replaced by a process of assimilation. This response sacrificed a small number of trees but saved as it were the forest. In order to achieve a good result, the Catholic Kings knew they could count on the sincere conversos: they placed the Tribunal of the faith in their hands.

Such are the facts. During these years 1475, the Catholic Kings requested the Pope for the authority to create an Inquisition which would also be royal, and which would curb the Judaizing conversos. In doing so they were repeating a similar demand made in 1461 by their predecessor Henri IV of Castile - a fact most are unaware of. Pope Sixtus IV acceded to this demand with his Bull Exigit sincerae devotionis of Novermber 1, 1478.

Then the Pope, following the recommendation of the Kings, named as Inquisitor-general, as we have already pointed out, the Dominican Tomas de Torquemada, who the royal chronicler and converso Hernando del Pulgar tells us was a relative of Cardinal Juan de Torquemada, and who like him was “of Jewish lineage and a convert to our holy Catholic faith.” Perez de Almazan, converso Secretary of State and the person responsible for the Inquisition, backed up this guarantee of a good result which was carried on by the successor of Torquemada, Diego Deza, another Dominican and yet another converso, as was proclaimed urbi et orbi in the first years of the Sixteenth century.

The Spanish Inquisition was created to cure a dangerous illness which suddenly and unexpectedly occurred during a national process of tolerance and Christianization. Daughter of these forces, she assured the definite success of the process in so far as it could be saved, namely Christianization. In Spanish eyes, the result of this good though risky effort, does not deserve the contempt of other nations such as France and England, nations which refused to take the same risks and which from the start rejected and expelled their Jewish communities.

THE FIRST EVENT THAT IS QUIETLY IGNORED

The Spanish Inquisition having been established in this spirit, two events rapidly occurred, two events about which current historians keeps silence, sometimes deliberately.

The first is the fact that, before giving the Inquisition permission to freely function, the Spanish monarchs suppressed the pontifical Bull of 1478 for a period of two years while they made a great effort to pacify the situation by means of persuasion. It was only in 1480, in the face of the “obstinacy of the Judaizers” that they appointed the first inquisitors in Seville.

During this period a campaign appealing to what Hernando del Pulgar describes as “sweet reasons and tender admonitions” was developed in Seville and throughout South-Western Spain. It was initiated with a pastoral letter - a veritable catechism for the conversos - by the Archbishop Gonzalez de Mendoza, who also published a special catechism especially meant for the Jews. A greater effort at evangelization was undertaken, including visits to homes and the placing of bulletin-boards in each parish on which the pastoral-catechism of the Archbishop was posted. It is the converso Pulgar himself who tells us in his chronicle that: “The religious to whom this mission was entrusted, initially worked to convert the Judaizers by sweet admonitions, then by harsh reprimands. But this was only minimally successful. In their obstinacy, the Judaizers gave proof of their blindness and stupidity and of such a passionate ignorance that they denied they were Judaizers and hid their errors, and then secretly returned to these errors and practices in order to preserve their Jewish rites.”

One searches in vain in the recently published Inquisition espagnole of the Toulouse professor Bartolome Bennassar and his five co-authors for any mention of these pacific efforts during the period prior to the initiation of Inquisitorial activities. As for the Histoire de l’Inquisition espagnole written by the British professor Henry Kamen, and which appeared in a French translation some thirteen years ago, it doesn’t hesitate to proclaim just the opposite: One reads in it that “no other measure was taken during the two following years [after 1478]. Pulgar[...] denounced any recourse to coercion at a time when no attempt at evangelization was even outlined.”

THE SECOND EVENT THAT IS QUIETLY IGNORED

The second event shows that the Inquisition not only envisioned the use of persuasion, but also that of reconciliation and assimilation. This is demonstrated by another important event which took place fifteen to nineteen years later, in 1495-1497.

This important episode is the Law of Rehabilitation (habilitation) initiated at that time by the Catholic Kings. By this procedure the monarchs exchanged the modest tax levied on all those condemned by the Inquisition during the course of the preceding 15 to 17 years, for the right to take public office and to ply the trades which had been prohibited to them and their decedents.

This general Rehabilitation of 1495-97 was laid out in detail in the archives dealing with the matter. Thus, for Toledo by F. Cantera Burgos, and of Seville by Father Azcona.The reading of these documents is of great interest for they give the names of the condemned, their professions, the reason for their condemnation and the penalties incurred during this initial period, the most rigorous of the Inquisition. One immediately sees that the number of those condemned was far fewer than the number given by the anti-Inquisitorial histories. So much for Seville.

One can find here a typical case. Thus, for example, among those rehabilitated in Toledo was a merchant named Juan de Toledo, or Juan Sanchez, the grand-father of St. Teresa of Avila, who despite the fact that he was condemned as a Judaizing converso, was given back all his professional and civil rights which made it possible for him to subsequently hold public office, that of tax-collector of royal and ecclesiastical revenues in Avila. And which further allowed him to see the nobility of his sons officially proclaimed by the chancery of Valladolid.

This is a model example of reconciliation and assimilation, especially when one considers the fact that the grand-daughter of this rehabilitated converso was to become one of the glories of Tridentine Catholicism, welcomed with respect and supported by Gaspar de Quiroga, the Inquisitor-general of her epoch.“I am happy to know you, for it is something that I greatly desire. Please see me as your chaplain. I will help you in any way necessary... I wish to tell you that some years ago a book of yours was presented to the Inquisition. Its doctrine was examined with great care. I have read the entire book and I maintain that the doctrine is very correct, very true and very profitable... You can take it back whenever you wish. I authorize you [to publish] it as you asked... I ask you to always remember me in your prayers.” The Spanish text is found in the Obras de Santa Theresa by Father Silvero de. S. T., T. I, p. 226: French translation of Marcelle Auclair.

But the reader will search in vain for any mention of this general Rehabilitation in the current histories about the Inquisition, even the most recent. The Inquisition espagnole of Bennassar and his collaborators only makes an obscure reference to “dispensations” which could be bought, and which only resulted in the further “weakening of the descendants of the old religious minority.”! As for the Histoire de l’Inquisition espagnole of Henry Kamen, it goes so far as to offer the reader a new falsification to the effect that “the Catholic Kings continued to apply the regulations” published by Torquemada in 1484 which imposed all sorts of professional and civil restrictions on the condemned and on their children and grand-children.

One sees that the attitude of people like Braudel who totally reject the current histography of the Spanish Inquisition is only too well justified. Unfortunately however, he offers the reader nothing as an alternative.

AN INCREDIBLE FAIRYTALE

It is clear then that what has been imposed on the public is an incredible fairytale: “The conversos were eliminated,” writes Henry Kamen; the Inquisition resulted in “the progressive extermination of the Jews,” claim two of the co-authors of Bartolome Bennassar. We have seen what happened to the Jewish converso grand-father of St. Teresa of Avila who became the wealthy tax-collector for the king and Church as well as the father of hidalgos to whom respect, franchises and honorable careers were opened by submission to the “executory letters of His Majesty” who raised them to the nobility. A Jewish converso became the grandfather of a saint revered as much by the Inquisitor-general as by “Don Felipe,” that is, King Philip II. This King was able to persuade the Papal Nuncio to recognize and support her Carmelite reform by means of this dry injunction: “It is time for you to honor virtue.”

If one goes on, beyond the period of origin, and examines the Inquisition in the 17th Century, what does one find? From 1607 to 1618 the Inquisitor-general was cardinal Bernardo de Sandoval y Rojas, who we have already noted as a patron of charity. And this Inquisitor-general was none other than a descendant on both his paternal and maternal sides, of those conversos who had been “eliminated” and “exterminated.”

On his mothers side he was a direct descendant of Juan Pacheco, the Marquis of Villena and the Grand-master of the Order of Santiago. This is the same person who Henry Kamen reminds us was a “descendant on both sides of the ancient Jewish family of Ruy Capon.” On his paternal side this cardinal was the direct descendant of Henrique Henriquez, the maternal uncle and the major-domo of Ferdinand the Catholic, and another person of Jewish origins.

At the same time, the Inquisitor-general, Pacheco et Henriquez were being “eliminated” and “exterminated,” these conversos controlled enormous seigneural estates in Spain. They also included among their number the Dukes of Escalona, the admirals of Castile, the Viceroys of Peru, Mexico, Sicily and even of Castile (Henriquez) in the absence of Charles V.

THE “CONVERSOS” WERE ALWAYS IN CONTROL, ESPECIALLY IN THE INQUISITION

The sister of the Inquisitor-general Sandoral married Pedrarias Davila, the Count of Punoenrostro and the direct descendant of Alfonso Cota, the Jewish treasurer of Henry IV of Castile. As a result she had step-cousins and step-uncles of Jewish origin which included Juan Arias Davila the Bishop of Segovia; the Latin poet Alvaro Gomez de Ciudad-Real; the seigneur of Pioz, the childhood page of young Charles the Fifth and his companion at Pavia; the conquistador Pedrarias Davila, the first governor appointed to the Americas; Louis Cota, the chaplain of Charles V and bishop of Ampurias; Sancho Cota, the private secretary of Eleonore, sister of Charles V and queen of Portugal, and later of France (she married Francis I); the Lords of Ventosa, Cota-Sandoval, etc., etc. It is obvious that all of these were among those who were “eliminated” and “exterminated.”

In reality, throughout the 17th Century, everywhere and above all in the Inquisition, the conversos of Jewish blood more than ever remained in power. More than ever they constituted the very marrow of Spanish civilization. They filed the most sought after positions in the chivalric orders, the highest positions in the religious hierarchy; they constituted the nobility, the government and the intellectuals of the nation.

Such a widespread and successful assimilation is without parallel in any other land or period of history. It was moreover, an assimilation inseparable from the Inquisition which was in turn supported and directed by the conversos themselves. Under such conditions the Inquisition could never have been used for the elimination or extermination of their blood-brothers; indeed, just the opposite was the case.

AFTER ALL, EVERYONE KNOWS IT IS SO

One is forced to ask oneself why current historiography tries to impose this fairytale of the “elimination” and “extermination” of the Jewish conversos everywhere outside of Spain, and this at a time when one cannot but be scandalized by the Jewish omnipresence among the Spanish elite. Such was recognized in Rome, France and the Protestant countries.

In the capital of Christianity this was noted by the Inquisitor-general Guevara at the beginning of the 17th century. In Holland Erasmus declared that “In Spain there are hardly any Christians to be found.” In France, or rather, in Pantagruel, Rabelais declared that all the Spanish are more or less Marranos (an insulting title given to the conversos suggesting that they were pigs). And again in France, the Huguenot Languet, a pamphleteer employed in turn by the Lutheran Elector of Saxony and the Calvinist Holland wrote in his Apologie du prince d’Orange (Apology for the Prince of Orange) (1581) that “I am not surprised a what the greater part of the world believes: namely, that the majority of the Spanish, especially those considered as aristocrats, are of the Moorish race or are Jewish.” All this should make us question the issue of Spanish racism.

A DECISIVE SUCCESS

Moreover, this is just as true with regard to quality as it was with regard to quantity. At no time in history did the conversos achieve the same glories as they did under the Spanish Inquisition. The process of assimilation resulted in such a striking synthesis that it changed the course of European history. In the face of the Reformation, the converso genius was a model of Catholicism both in the strength of its resistance as well as in its ability to regain what had been lost.

Moreover, the Spanish Jewish conversos of that period, were not limited to Inquisitor-generals, to people like Sandoval, the great patron of letters, or St. Teresa of Avila, the Carmelite responsible for the magisterial renovation of mystical monasticism. It also included people like the layman Luis Vives, the glory of Catholic humanism in the outpost of Flanders ;Francisco de Vitoria, the Dominican renovator of social and moral theology who was also the head of the University of Salamanca; the great Augustinian poet and theologian Luis de Leon; Jean d’Avila, the apostle of Andalusia and the person responsible for inspiring Ingatius of Loyola; Diego Lainez, successor of Ignatius of Loyola, general of the Jesuits, the person responsible for animating the Council of Trent, and a person who almost became the Pope of the Counter-Reformation; and Arias Montano, the great bible scholar of the period. And finally one must mention innumerable Jesuits, for the Spanish conversos flocked to the Company of Jesus which had taken over the leadership of humanist and religious culture, blocking and even driving back the Reformation throughout Europe.

A typical example is that of the five sons of a wealthy merchant of Medina del Campo (who was no more “eliminated” or “exterminated” then were the other conversos), all of whom entered the Company of Jesus. Among them was Father Jose de Acosta, one of the first naturalists to use modern scientific methodology, the author of the remarkable Historia naturel y moral de las Indias (de America), and a close advisor to Philip II. Another brother was Father Jeronimo de Acosta who warmly approved the apology for the Inquisition written by the prior Juan-Francisco de Villava, declaring its “holy and Catholic doctrine most profitable and necessary for our times,” and describing it as a “most fruitful and savory work... worthy of the great master of Avila.”

Catholics cannot but recognize their debt to this unique achievement - the spiritual renewal in the heart of the Church - given to the world by the Spanish Jewish conversos. To anyone who considers the facts objectively, this happy result is one of the great facts of civilization

A BREATH-TAKING SCENE

But, on the other hand it will be objected that, the Inquisition forced the expulsion of the non-converted Jews from Spain starting in 1492, twelve years after the establishment of the first Inquisitorial tribunals. This is what the anti-Inquisitorial historians affirm and have affirmed since the historian Llorente made the claim based on an anecdote recounted by Paramo, an Inquisitor in Sicily, at the end of the 16th Century.

This story claims that Torquemada in a fit of anger, threw a Crucifix before the feet of the Catholic Kings and told them that, having been blinded by the brilliance of Jewish gold which was being offered them at the time, they had sought like Judas, to sell Christ. The Catholic Kings, terrorized by the Grand Inquisitor, hastened to sign the decree for expulsion which was before them.

This dramatic scene was made very popular by Emilio Sala, a “hack” painter at the end of the 19th Century who made a profession of painting many historical scenes. Subsequently it has been repeatedly reproduced and disseminated.

The fact is that this breath-taking scene cannot be confirmed from any records or witnesses of the period. Paramo, who Braudel, as we know, considers a very unreliable authority, obviously invented the story to please the anti-Jewish Spaniards of his time.

Even Jewish historians refuse to authenticate this anecdote. The Chebet Jehuda, a sort of history of the persecutions which the people of Israel have undergone, cites Abrabanel, Jewish financier to the Catholic Kings, as witness that Torquemada and the Inquisition in no way intervened in the decision to expel the Jews which this text imputes to Queen Isabella. According to Abrabanel’s own testimony: “Do you believe this came from me?” Isabella said. “The Lord put this thought in the heart of the King.”

Regardless of whether the monarch who was most responsible was Isabella or Ferdinand, the decision to expel the non converted Jews was a royal one and completely outside of the Inquisitorial framework. This is confirmed by the preliminaty statement of the decree for expulsion: the inquisitors are mentioned among those responsible for providing information which led the monarchs to take this decision, but also, according to the declarations made by the Cortes (Parliament) of Toledo which met in 1480,”many other people, religious, ecclesiastic and lay.”

A PROCESS OF DECOLONIZATION

Among “the great number of reasons” (Azcona) for the expulsion, the preliminary statement mentions the havoc resulting from the pressures exerted by the Jews on the conversos, as well as the crimes imputed to the Jews. Beyond these justifications one must remember that the decision immediately followed the capture of Grenada which put an end to the Moslem occupation in Spain and that the event was obviously seen, as Braudel put it, as the final “liberation” from these “strangers from across the sea.”

This author adds: “In order to be part of Europe, the Spanish peninsula, in a process which to some degree resembled that of decolonization, refused to be African or Oriental.”

The Inquisition had no part in the execution of this decision. The orders were given solely to governors, judges and inspectors. And none of the goods of the Jews benefitted members of the Inquisition. The possibility of avoiding the expulsion was offered to the Jews if they converted, and 50,000 of them chose baptism which went to further swell the number of conversos. The royal instructions made it clear that in cases of conversion, the Inquisition would create no problems during the years necessary for their adaption, and that they would receive special consideration. Once again, in the mind of the Catholic Kings, the Inquisitorial aim appeared in itself to be good, not one of repression at any price, but of assimilation. This was made even more clear in that the monarchs agreed to act as God-parents to some of the new conversos when they were baptized. Thus for example, they function as God-parents in the celebrated baptism of the financier Abraham Seneor and the Rabbi Mayer de Guadalupe monastery, to whom they later committed important functions of state.

A TRULY BIRACIAL SYMBIOSIS

In point of fact the real number of those expelled was only about 100,000, of which a considerable number returned to Spain a few years later where they were accepted without being required to give very exacting proofs of their conversion. This was shown by the complaint addressed in a memoir to Charles V by the licentiate Tristan de Leon. Once again the number of conversos increased.

At the end of the 15th Century, as a result of successive waves of conversos from the peak of the Middle Ages to the time of Charles V, the conversos constituted the greater majority of the Spanish Jews, some 400,000 persons in a population in Aragon and Castile that totaled 5 million.

This important fact and the proportion off conversos to Old Catholics should not be forgetten if one wishes to understand the enterprise of assimilation undertaken by the Inquisition. Moreover, most of the conversos belonged to the economic, cultural and administrative elite and had equal opportunity in these areas with the older established Christians. The cultural and religious outcome of the Inquisition was thus a veritable biracial symbiosis involving the nearly total assimilation of the Jewish population.

THE VICTIMS OF THE INQUISITION - STATISTICS GONE MAD

But it will still be objected that this effort involved an incredible number of victims, a veritable orgy of killing. If one believes the recent denunciations of Inquisitorial horrors such as those made by Pierre Guenoun, the air of the Peninsula was “infested with the smell of burning flesh” during this period. And another recent historian, Pierre Dominique, gives us details of the number of victims, reign by reign, victims which were, at least in the beginning, mostly Jewish conversos. Thus, during the reign of the Catholic Kings (Isabella and Ferdinand):

Burnt alive Burnt in Effigy Punished 16,376 9,901 178,382

And according to the enormous figures cited by Henry Kamen, from the end of the 15th to the beginning of the 19th Century the victims added up to:

Burnt alive Burnt in effigy Punished 31,912 17,659 341,021

Encyclopedias, dictionaries, and scholarly publications have repeated these figures so often that the public mind is convinced they correspond to the truth and that the Spanish Inquisition was one of the most ferocious and most criminal oppressions ever known to History. Prejudice is so strong that these numbers continue to be accepted without criticism, despite the devastating criticism of them by the German historians such as Ernst Schafer from the 1900s, or the Spanish historians such as Alfonso Junco and Nicolas Lopez Martinez between the year 1930 to 1950. Thus it was necessary for Braudel to note in passing that “the number” of victims of the Spanish Inquisition “was relatively small,” and for the British author Kamen to note in the French translation of his Spanish Inquisition that the numbers given “are not based on any foundation” in order to enable our historical studies to begin to raise doubts about them. However it was necessary to wait until 1975 before any publication reaching university circles dealt in a definite manner with the issue, and which demonstrated that they were truly a product of preposterous statistics .

A NAIVE IMPOSTURE

These [false] numbers come from the first historian of the Inquisition, the Spanish Llorente, a refugee in France because he had been the representative of Joseph Bonaparte during the occupation of Spain by Napoleonic troops. He wrote the Anales de la Inquisicion de Espana (Madrid, 1812), and then a Histoire critique (sic) de l’Inquisition d’Espagne (Paris, 1817-1818). A restatement and correction of these numbers was made in 1975, and then only in the single study of Professor Gerard Dufour of the University of Rouen under the title of “Les victimes de Torquemada (Les calculs de Llorente: sources et methodes), published in Cahiers du monde hispanique et lusobresilien, a bulletin of very limited circulation published by the university of Toulouse-Le-Mirail.

Professor Gerard Dufour shows that the impressive numbers of Llorente which are almost universally accepted are “not at all convincing.” They are in no way a reasonable statistic, but only the naive imposture of purely conjectural numbers established on the basis of insupportable fragility and exaggeration. How did Llorente arrive at his figures? The answer is quite simple. Totally ignorant of the number of victims of the Inquisition, he fabricated them from conjectural accounts available to him with regard to the tribunal of Seville during the first years of its activity, numbers provided by the early chroniclers and historians and a lost inscription. As Mariana, one of the ancient historians, pointed out, Llorente did not take note of the fact that these numbers were only rumors. Moreover, carried away by his passions, Llorente quoted inexactly and exaggerated greatly in his additions. For, as Gerard Dufour noted, among the 2,000 victims mentioned by Mariana were included some added up by Llorente, and the 700 mentioned by Bernaldez, the anti-Semitic chronicler who moreover had inflated the number to satisfy the needs of his cause. Llorente did not take all these facts into account.

Having thus taken “entirely erroneous numbers,” and these only from Seville during the early years, Llorente tranquilly multiplied them by the total number of Inquisitorial tribunals and by the number of years they functioned.

But as he arrived by means of this method of blind multiplication of inflated figures at a total figure that was so enormous as to be absolutely unbelievable, he reduced them on a completely arbitrary basis by 50% in general, and by 90% for the first year after each tribunal was established because they would not have had sufficient time to pronounce sentence on anyone during the first year.

In summary, all of Llorente’s numbers, which Pierre Dominique, declared as late as 1969, “constituted the basis for our knowledge on this subject” and merited “to be believed” were from beginning to end, nothing but suppositions. Anti-Inquisitorial passions were so strong that during a century and a half, historians, authors of dictionaries, encyclopedias, manuals, and all the readers of Llorente pretended not to have read what he so ingeniously proclaimed himself... Thus he wrote in Chapter VIII, Article IV of Volume I of his so badly named Histoire critique: “I was satisfied with supposing that the thousand condemned were simply burnt in person; that only five hundred were burnt in effigy: based on this calculation, each year 32 individuals were burnt in person,” etc.

SEVERAL HUNDRED

In fact, concludes Gerard Dufour: “In the absence of precise documents and limited to a given tribunal or a given time period, it is impossible to claim to be able to ‘imagine’ the total number of victims of the Holy Office at that time.” And nothing could be worse then to base one’s opinion, as did Kamen, on the estimations given by the American Henry-Charles Lea, the author of the enormous History of the Spanish Inquisition which is as prejudiced as Llorente’s work while being (much) less ingenuous, a fact which makes it even more one sided.

Fortunately, objective historians exist today, men for whom only the facts as reported in the archives can be relied upon. Thus the Franciscan Father Tarsicio de Azcona, who we have already quoted with regard to the reign of Isabella the Catholic, draws exclusively from the archives of the period which he often uncovers for the first time. This enables him to rectify innumerable gross errors on a wide variety of topics such as public mandates, financial reform, the preparation for and the financing of the conquest of America and the assimilation of the Moors after the fall of Grenada, etc. These are all subjects about which Joseph Perez, the most recent French specialist and author, among other works, of L’Espagne des Rois Catholiques , expresses his heavy debt to Father Azcona who he characterizes with praise as being a “ scrupulous historian.”

Now after the most rigorous and extensive research possible on the period of the reign of Isabelle the Catholic, Azcona draws this conclusion about the victims of the Inquisition: “Those condemned to death during the reign of Isabella [which is to say between 1480 and 1504 were unquestionably in the hundreds.” .

EXECUTION WAS THE EXCEPTION

One should not mistrust the estimates of Father Azcona because he is a religious and a Spaniard; historians in every land and in various fields accept his authority. One can also have confidence in the work of Gustav Henningsen, a layman of Lutheran persuasion from the North (Denmark) who also restricts himself to information derived from the archives. For a later period of the Inquisition he gives us an estimate which agrees with that of Father Azcona. Having discovered in the 1970s some 50,000 inquisitorial procedures dating from 1560 to 1700, he concludes “only about one percent of those accused were executed.” This would be about 500 victims for a period of 140 years during this most important period of Inquisitorial activity.

Admittedly the Inquisition would have been more moderate during this period, as compared to the Isabellan era, for the problem of conversos had been resolved as a result of assimilation. But the estimate of victims given by Azcona was only for a 24 year period. And the only numbers from the very beginning of the Inquisition concerning continental Spain, and not found in Lea are those quoted by Kamen of the tribunal of Badajoz furnished by a recent inquiry published in the Revue des etudes juives. And this source reduces the number to some 20 executions in 106 years between 1493 and 1599 in one of the “hottest” regions of Spain.

Once again it is confirmed that repression was not the essential goal of the Inquisition. Once the danger of a socio-national explosion was passed, they refused to apply the ultimate penalty in 99% of the cases. The historian is forced to note that the estimate of the number of victims of the Spanish Inquisition as revealed by Azcona and Henningsen are much lower than those that one fears would have occurred with the spontaneous massacre of conversos had the Catholic Kings not stopped the blood bath by the institution of the Inquisition. In Toledo alone, more people were killed in the two massacres which lasted several days, than were killed by the Inquisition during the 25 years of Queen Isabella’s reign. And in addition to Toledo, there was Ciudad Real, Jaen, Sepulveda, Cordoba, Segovia and all the other cities which would have followed their example. The situation in neighboring Portugal provides further evidence of this. There the Inquisition, such as existed in Spain was not established until 1586, and massacres of Jewish conversos continued to claim thousands of victims in a population that was barely a quarter that of Spain, and this only in a few decades.

RELATIVE TO WHAT?

We thus come back to what is described by Braudel as the “relatively limited number of victims” of the Spanish Inquisition. But what does “relative” mean? It means that, not only in Portugal, but throughout most of Europe, the victims of religious intolerance were much larger. In England the Reform of Henry VIII led to the execution of two cardinals, two archbishops, 18 bishops, 13 abbots of large monasteries, 500 priors and monks, 38 University Doctors , 12 Dukes or Counts, 164 noblemen, 124 private citizens and 110 women. And this without the excuse of any particular reasons of State (the Jews had been expelled from England in 1290), while Spain was faced with the need to establish an expensive line of defense against the anarchic massacres of conversos. And in England the “Bloody” Tudor Mary, this time on behalf of the Catholics, did the same thing as Henry VIII. And Queen Elizabeth I indiscriminately killed Catholics and Calvinists in even larger numbers. And the English Puritans under Cromwell who engaged in pure and simple genocide in Ireland - 40,000 victims killed or sold as slaves in 1649 in the Oradours of Drogheda and Wexford alone.

Was there not a succession of horrors in Germany and throughout the areas under Lutheran control claiming hundreds of thousands of victims from the very start of the Reformation? The War of the Knights, the War of the Peasants, the subversion of the Anabaptists, all operations initiated in the name of the Reform, all drowned in blood, and all instigated by the oft frenetic leadership of Luther himself. In Germany and in Sweden the Lutheran Inquisitions were continuously employed, as were in Switzerland the Zwingalian or Calvinist Inquisitions, killing the Anabaptist Manz, or the Osiandriste Funke, or the tolerant chancellor Crell, or the “libertine” Gruet, or the anti-trinitarian Servet, or the Karlstattian Jonas, etc., etc.

And finally France. Even without speaking of the Wars of Religion in which hundreds of thousands of victims were killed, the repression of heresy among the people was extraordinary bloody. As is documented, in Paris from 1530 the execution blocks continuously were reddened with the blood of the victims. And after this the 3000 victims of the massacre of the Vaudois of Provence ordered by Francis I in 1545. And then the 500 condemned to death by the Parliament of Paris alone between the years 1547 and 1550.

And what if we add to all this, to the Lutheran killings in Germany, to those of the Puritans in England, to the Calvinist killings in Switzerland, the tens, and even hundreds of thousands of victims of the suppression of “sorcerers and witches” which the Inquisition in Spain alone, as we shall see, was able to prevent.

TWO CONTEMPORANEOUS WITNESSES

Again, those living at that period of history, if they were in a position to make a comparison, were not likely to be wrong. Thus Philip II, who tried to moderate the actions of his wife Mary Tudor, and who had a first secretary inherited from his father Charles V, Gonzalo Perez who was a converso and who had a “decisive part” in state affairs. Familiar with the situation in Flanders after having been the regent of Spain, Philip II noted on his return to the Peninsula that the Inquisition in the Low Countries had been “much more cruel than here.”

Thus Antonio del Corro, a Protestant pastor born in Seville and related to a well known Inquisitor of the same name. He had known the works of Luther and the other reformers because the official Inquisitors in Seville gave him confiscated copies of their works. Converted by reading them he became the pastor of the reformed French Churches in Aquitaine, then at Anvers, and finally in London. He wrote in 1567 that the Spanish inquisitors before his departure from the Peninsula “had a great deal of respect for him.” He was on the other hand insulted, menaced and anathematized by his new Calvinest brothers, especially by Theodore of Beze, and then excommunicated by the Bishop of London. He wrote the following statement in London in 1569: the Protestant Inquisitions exercised “a much greater and more unjust oppression and tyranny [on its victims] than did the Spanish Inquisitors.”

THE FRIGHTFUL “GANG OF INQUISITORIAL COLLABORATORS”

But let us look at things in the concrete. Let us start by following a man or a woman who assisted the Spanish Inquisition. That is to say, one of the “collaborators” who we are told were omnipresent and terrible denouncers, the “spies spread abroad,” a sort of “secret police” appointed as Kamen specified, “without any record of their appointment being kept.”