Posted on 01/27/2016 1:49:00 PM PST by NRx

As we continue to commemorate the feast of the Lord's Baptism we are going to begin posting in parts the story and reflections of one of our authors' conversion to Orthodoxy, Ryan Hunter, a student at New York University.

* * *

"In His unbounded love, God became what we are that He might make us what He is." --St. Irenaeus (d. 202)

I am in love. The object of my affection, or rather, my devotion, is not a person per se, though it is very much alive. It has been alive for 2,000 years, persisting through seemingly insurmountable odds, and in that time it spread from the eastern shores of the Mediterranean north and east, ultimately to the shores of Alaska and the New World. Now it is very much established and thriving here in the US. What is this thing that has become such a defining part of my life?

I have fallen in love with the Orthodox Church.

It is difficult for me to render into words an account of the transformation that this awakening has wrought in all areas of my life. I feel myself to be at last truly satisfied, spiritually and emotionally. I feel enriched beyond description after years of an ever-present void. From the depths of my heart I sense that I am now a more fulfilled Christian, and above all I know that I am a more inspired human being. Sadly in this increasingly secular society, many people my age do not want or desire such inspiration.

For the rare college student who craves a deeper inspiration that goes beyond a routine weekly church hour, for anyone who wants to enter into a new level of spiritual life, I urge him or her to consider Orthodoxy. It has awakened in me a kind of spiritual consciousness that I never imagined I would experience, a kind of spiritual inspiration that very few of my non-Orthodox friends have today.

For this awakening, I am, and will always be, forever grateful.

Introduction:

"Remember constantly that the light of your soul, of your thoughts, and of your heart comes from Jesus Christ."

St. John of Kronstadt (1829-1908).

Before I begin, I wish to thank two dear friends who have had the biggest impact on introducing me to Orthodoxy, Rebecca Dixon and Gillian Davies. They exemplify all that is best about the faith first and foremost in their incredible kindness and warmth. They are two of the most intelligent, cultured, and open-minded individuals I have ever met. Typical of most Orthodox who encounter a would-be-convert, they would probably tell you that they had little to do with my spiritual journey, saying such a thing is something that can only begin and evolve in the individual's heart and soul.

But they did more than simply start me off on my journey. After I met them when I started attending weekly 5 pm Orthodox Vespers at Kay Spiritual Center at American University during the fall 2010 semester, they provided me with so much counsel and encouragement. They were welcome and informative company to the Sunday Liturgies I insisted on attending as often as I could. They answered the many questions I had, and introduced me to two beautiful churches. Most of all, they shared with me their own unique personal experiences with Orthodoxy.

St. Sophia Greek Orthodox Cathedral in Washington, DC

St. Sophia Greek Orthodox Cathedral in Washington, DC

I think Gillian understands. She proved invaluable in helping me improve on my Greek-reading, though I think I will continue to pronounce the letter 'tau' incorrectly in many instances! In our walks to and from church during Great Lent on Mondays when we trekked over to hear Fr. Dimitri sing the office of Great Compline, she shared her thoughts on the Faith, the Church, and some of her own personal views on its teachings and St. Sophia's own traditions, as a parishioner and someone who was "cradle" Orthodox. I realized that by entering the Church, I would not be required to subscribe to some sort of ideological litmus test, but be encouraged, in every liturgy, and indeed, in every moment of my life, to believe in the Orthodox way, and put its teachings into practice. Thanks to Gillian I have come to appreciate how the Church stands for certain things, and does take specific positions on contemporary issues, but it does not focus so much on projecting an absolute image of itself to an ever-changing world as much as it emphasizes staying true to its rich Tradition.

As soon as I met Rebecca I saw that she has a love for life and an infectious spontaneity, twin attributes inestimable in any friend. Although she was only in DC during the fall 2010 semester, we've kept in touch, especially on Facebook where I love to share my latest stories and updates about my spiritual life at St. Nicholas Cathedral, the church she introduced me to in November. She loves to converse on all manner of things, from travelling abroad (she recently was in India spending her summer in New Delhi and Kashmir) to Canadian politics (she worked in the Library of Parliament in her native Ottawa) to different cuisine and languages.

St. Nicholas OCA Cathedral in Washington, DC

St. Nicholas OCA Cathedral in Washington, DC

She is a member of the Orthodox Church in America, an autocephalous (fully self-governing) body of several hundred thousand Orthodox in the US, Canada, and several communities in Central America. In addition to its Russian roots, the Church has a large and steadily growing number of members entering from mostly mainline Protestant groups, but there have also been considerable numbers of Catholic converts, as well as some evangelical Christians who have all come to Orthodoxy in recent years through the OCA.

His Beatitude Metropolitan Jonah, primate of the Church from 2008 [to 2012], has said in interviews that,

"Our churches embrace a very broad diversity of peoples across the continent."

Rebecca's family exemplifies the incredibly embracing diversity of the OCA; her mother's family is religiously Jewish, and her mother made the difficult decision to enter the Church after she was born. Rebecca explained how her mother did not want to lose any of the cultural heritage with which she had grown up. After much thought and prayer her mother came to realize that embracing Orthodoxy did not mean she had to give up her family or her Jewish cultural roots. According to Jewish custom, which passes on the faith tradition through matrilineal descent, Rebecca and her mother, in addition to being Orthodox Christians, are also, and will always be, Jewish. As someone who has Jewish roots on my mother's side of the family, I always thought it was beautiful that Rebecca could be both Jewish by heritage, and a Christian in her religion.

In addition to Rebecca's wonderful sense of humor, and what I would describe as the enormously helpful "education" that she gave me on really "all things Orthodox", she also enlightened me early on in my studies of Orthodoxy, as I became increasingly interested in converting, that the OCA was no stranger to controversy. The Church has been going through controversy in many ways as painful as that which has been engulfing the Roman Catholic Church in recent years (albeit of a different cause.) I'm so grateful that she had the strength and forthrightness to share this with me.

More than anything else, I am grateful to Rebecca for introducing me to Saint Nicholas Cathedral, two blocks down Massachusetts Avenue from St. Sophia. This church is the primatial cathedral of the Orthodox Church in America, and it has been my spiritual home ever since that November day when she first took me with her to experience the Divine Liturgy there.

Finding Orthodoxy: The Beauty of the Faith and the Soundness of its Teachings

I will first address an area that is of less importance compared to the other doctrinal reasons behind my conversion, but still very important to me: the incomparable beauty of Orthodox worship.

I have never come across anything quite like the Divine Liturgy, the Eucharistic liturgical service of the Orthodox Church. As St. John of Kronstadt observes in his "Thoughts on the Divine Liturgy",

"The divine services are a blessed fount from which the heavenly Grace abundantly pours forth its gifts upon all those who serve the Lord in fullness of heart--gifts of mercy, peace, consolation, purification, sanctification, enlightenment, healing, renewal, and--what is most precious--the gift of worship, in Divine Liturgy and Holy Communion."

This "blessed fount" contains a beauty that is so transportive, so moving to the soul that once I experienced it for the first time, I had a powerful sense that something in me had changed forever.

Before I experienced the Liturgy for the first time, I had no idea such ethereal worship existed in Christianity. For many students who were raised in one of the Western Christian traditions, used to a primarily logical and rational approach to theology and spirituality, Buddhist and Hindu devotional practices can often seem refreshingly mystical, offering a more beautiful, transcendent approach to the divine. I know of many former Protestants and Catholics who have moved away from Christianity to pursue these mystical practices, leaving behind faith in Christ largely because they were bored or disillusioned with the only form of Christianity they knew. They were not generally grappling with issues of Christian soteriology or theology when they left, but simply found themselves drifting, disconnected from any real deep sense of spiritual engagement, challenge or fulfillment as Christians. Unfortunately, they were unaware that Eastern Orthodoxy exists and that for centuries it has offered its faithful a profoundly mystical- yet still a corporate and communal- approach to God.

Within the life of the Church, our path to theosis is not some lonely climb on our own unique "spiritual journeys" as an island unto ourselves, for such an approach to faith leaves anyone ultimately feeling alone and vulnerable. Nor is the Church's admonition that life in Christ requires a life lived together as His living Body a burdensome, narrow-minded insistence that we obey its "rules". Rather, the Church insists we partake of and unite with the Body of Christ literally, communally, and liturgically because she recognizes the most basic truth about the human person: man is created in the image of God, and thus finds his highest fulfillment as someone who worships God and rejoices in His presence. The Church holds that the most beautiful and fulfilling way to worship God is in the Divine Liturgy, her principal worship service. Man is thus, at his core, a liturgical creature.

Like any Liturgy, such rejoicing is always magnified when it occurs with many worshipers present adoring God, rather than a few faithful standing by themselves at a sparsely attended weekday service. At these weekday services one gains so much wisdom and becomes even more aware of the fullness of the Church's liturgical life and her constant witness of the Gospel, but undoubtedly the occasions of greatest rejoicing are when the whole congregation joins together at wedding liturgies, the great Feasts of the Church, chrismations and baptisms, etc. These occasions are always filled with great rejoicing because they are a time of true, organic fellowship and community as the Body of Christ united around the bishop.

The Church recognizes that each human life is of immeasurable value and absolutely unique, and any bishop will tell you that our experiences of God differ from person to person. For instance, if you ask parishioners to name at what point in the Liturgy before communion they feel closest to God, or which liturgical prayers move them the most, you will get many different answers. Some people feel most comfortable praying alone in the quiet of their room; other people like to pray silently as they go about during their day, etc. A way to think of this is that we travel at our own pace, with our own distinct gait, but we are all on the same path, the Orthodox Way. Crucially, we unite ourselves, by the grace of God, to this Way, which offers the faithful union with Christ within His Holy Church. It is this unity in faith which is so crucial in the Church which has been preserved for centuries in the inner life of the Liturgy and the other divine services.

Many students today use meditation to find and center themselves, seeking to rise above the innumerable stresses of the world. The Church exhorts us to meditate on Christ, but not for the ultimate purpose of achieving a kind of nothingness or emptying of one's very soul in moksha or nirvana. In her ancient witness she provides healing for the whole of the human person--the body, the spirit, the soul, and the heart--by helping the faithful connect to the divine. For those of you who are practitioners of any of the Buddhist or Hindu traditions, or interested in these practices, I would especially urge you to visit your local Orthodox church. There is such a rich treasure of Christocentric meditative practices within Orthodoxy's ancient Tradition that any person's appetite for mysticism can be more than satisfied by the meditative practices of the Holy Church.

What one discovers as one comes more and more into Orthodoxy is that the Church does not exist to entertain people, as some churches attempt to do in efforts to "grow" their congregations on corporate models, nor is the Liturgy simply about "making people feel good", but it is about renewal through and in and by our life in Christ. This lifelong transformation in the image of God is, in all humility, richer and more transcendent than any of the non-Christian Eastern practices I have read about, participated in, or witnessed. I have read and experienced so much of other faith traditions, and there is truly nothing else like Orthodoxy. If you come to the Liturgy, you will experience what I describe with your own senses, your own soul.

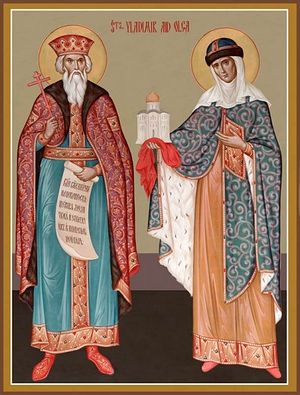

Sts. Vladimir and Olga

Sts. Vladimir and Olga

While Christianity had already made limited inroads in the lands surrounding Kiev, the principality's most recent ruler, Vladimir's father Svyatoslav, had been a pagan. Vladimir sent his envoys abroad to look into the religions of the world and recommend the one they found most fitting for the Rus. After experiencing the Divine Liturgy in Constantinople, the envoys were moved to choose Orthodoxy after previously having witnessed Muslims, Jews, and Catholics at prayer. Describing the liturgy celebrated in the Great Church of the Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) in the Byzantine capital, the envoys wrote to Vladimir:

"We knew not whether we were in heaven or on earth, for surely there is no such splendor or beauty anywhere upon earth. We cannot describe it to you: only this we know, that God dwells there among men, and that their service surpasses the worship of all other places. For we cannot forget that beauty. . ."

Importantly, the envoys make no mention of Orthodox dogma or teachings, which were nevertheless speedily brought to Russia along with Byzantine art, architecture and court etiquette following 988 when Vladimir and many of his people embraced Orthodoxy. Vladimir also eagerly married Anna Porphyrogeneta, sister of then-reigning Byzantine emperor Basil II "the Bulgar-Slayer." It's worth noting that the envoys, having travelled throughout all Europe and the Middle East, commented that

"surely there is no such beauty anywhere on earth."

They were at last satisfied that they had found a religion that brought them closest to God. I am reminded whenever I hear this story of Saint Augustine's beautiful quote in his Confessions:

"Thou hast made us for thyself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they find their rest in thee."

When the envoys reported

"we knew not whether we were in heaven or on earth",

their description of the liturgy is certainly fitting. Anyone who has ever been in an Orthodox church, who hears the mesmerizing chanting of the choir, anyone who contemplates the array of holy icons and frescoes that gaze down upon the worshippers along with the angels and "heavenly host" in the dome will know what the envoys meant. You need only to smell the sweet incense, with which the priests repeatedly bless the church and the people, as it rises toward the heavens to feel as the envoys did that

"God dwells there among men."

The Liturgy is above all else a reflection on earth of the splendor and richness of heaven. In it, heaven and earth are united in the sacrifice of the Eucharist, the holy oblation, of Christ Himself on the altar. Many Orthodox are unsurprisingly very devoted to it. Since the word "orthodox" denotes not only "right belief", but also "correct worship" and "correct glory", some Orthodox consider the manners in which other Christians gather to worship God to be inferior when compared to the complete worship rendered to God in the form of the Liturgy. This can sound insulting, but it is not meant to be. Many believe that to honor God with anything less than the most beautiful expressions of love, appreciation, and reverence refuses Him the full glory we owe him and the full honor He commands. Since the Orthodox see human beings as

"Liturgical creatures who are most truly themselves when they glorify God, and who find their perfection and self-fulfillment in worship,"

Taking active part in the liturgy itself offers a means for Christians to aspire to that kind of perfection through intent concentration on the divine. As Matthew 5:48 reminds us,

"Be ye perfect, therefore, even as your heavenly Father is perfect."

It is through participation in the inner life of the Church most fully expressed in the Divine Liturgy that man begins and continues on his path toward perfection, toward the divinization of his very being.

As Bishop Kallistos observes in his much-acclaimed The Orthodox Church the Liturgy is something that

"Embraces two worlds at once, for both in heaven and on earth the liturgy is one and the same--one altar, one sacrifice, one presence."

Similarly, St. Germanus, an early Patriarch of Constantinople (r. 715-730, d. c. 733) wrote that

"The church is the temple of God, a holy place . . . an earthly heaven in which the supercelestial God dwells and moves."

This is a fitting description of the liturgy; each Sunday is not merely a gathering of the local congregation of the faithful in remembrance of God's loving kindnesses and Christ's sacrifice, nor is it only a sacrifice by the people, but a kind of celestial gathering, with the heavenly saints and angels dwelling among the earthly in worship. In the liturgy the faithful are

"Taken up into "heavenly places" . . . and the Church universal, the saints, the Mother of God, and Christ Himself" are all present.

Anglicans, Lutherans and others of the Reformed tradition will notice, often to their immense surprise, that the Divine Liturgy contains numerous references to Holy Scripture. Bible passages are chanted at every service, sung by the choir in the form of Old Testament psalms while priests will chant the Gospel passage. Mary's Magnificat (taken directly from Luke 1:46-55) is beautifully sung at each All-Night Vigil in the Slavic tradition (Orthros in the Greek tradition) and the "Our Father" prayer is sung by the entire congregation at every Liturgy. Bishop Kallistos tells us that

"Orthodoxy regards the Bible as a verbal icon of Christ . . . in every church the Gospel Book has a place of honor on the altar; it is carried in procession at the Liturgy and the faithful kiss it."

The faithful bow their heads whenever the deacon or priest holds the Bible aloft and carries it out to the lectern during the chanting of the prokeimenon. This is not because we 'worship' the Bible, but because we consider it proper and fitting to treat it with the reverence it deserves as inspired of God.

In contrast to Orthodoxy, Western services are uniformly shorter in length, condensed in form, and feature considerably less singing. Since all mainline Protestant churches have their origins during the time of the Classical Reformation or shortly after, the structural basis for most Protestant services originates with the Roman Catholic Mass, which, unsurprisingly, given its shorter length, contains less scripture than the Orthodox liturgy. Today, contemporary Episcopal communion services in the US are nearly identical in form, content, and substance to the existing Ordinary form of the Mass, while Luther's Deutsche Messe, even considering his advocacy of sola scriptura and the changes he made to the Western liturgy, bears a very similar resemblance to the current Roman liturgy.

In order to give you a sense of how old the roots of the Divine Liturgy are, and how it has withstood the test of time despite medieval wars, many church councils, the brutal oppression of the Ottoman Turks, and more recently communist Soviet attempts in the past century to exterminate the Church entirely, the main liturgical form celebrated on Sundays is the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, an early Church Father who died in the year 407. In his 1984 translation of St. Germanus' On the Divine Liturgy, Dr. Paul Meyendorff, a prominent American Orthodox author, editor of St. Vladimir's Theological Quarterly, and Alexander Schmemann Professor of Liturgical Theology at St. Vladimir's Seminary, cites a noted Byzantine scholar who observes that the final developments in the Constantinopolitan or 'Byzantine' Rite occurred between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries prior to the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453. Most historians trace the core development of the Eastern liturgy to between the first and seventh Ecumenical Councils of the early Church, in other words, between 325 and 787 when the 'Triumph of Orthodoxy' occurred with the restoration of icon veneration.

The Russian Orthodox liturgy assumed its present form shortly after Patriarch Nikon ordered corrections to the Russian liturgical structure beginning in 1653 in order to bring his Church in line with the liturgical practices observed in Constantinople. By comparison to any of the variants of the Byzantine Rite, the current Ordinary form of the Roman Catholic Mass dates to only forty years ago in 1969 when Pope Paul VI promulgated the revised Novus Ordo form after the reforms enacted at Vatican II.

Orthodoxy has admittedly had its own periods of liturgical change, but these occurred centuries ago and did not result in any Orthodox doctrinal teachings being altered or abandoned. The liturgy remains the unchanging cornerstone of faith and worship. What does it say about other branches of Christianity that so many worshippers either feel unfulfilled by their services as they currently exist, or that some churches hold councils and parish meetings where a majority vote can strip a service of many of the things that define it as Christian? Many of my Catholic friends do get a sense of spiritual fulfillment from the Mass, and this is wonderful, but none of them have exhibited the kind of enthusiasm for it which I have encountered among Orthodox anticipating the Divine Liturgy. Granted, most of these friends are "cradle Catholics" who grew up with the much-abbreviated Ordinary form of the Roman rite, as I did, but I have never met a Catholic who felt the depth of transcendent inspiration that I've witnessed so many Orthodox feeling during the Divine Liturgy.

I do not claim that all people who have ever experienced the Orthodox liturgy find it to be the most beautiful of any Christian service. That is simply not true; if it were, the Church would certainly have many more converts each year than it already has. But among all Orthodox, you will find almost no one--certainly no one prominent or respected--wishing to alter the Liturgy's wording or, worse, omit any of it. This happiness and deep satisfaction with the existing age-old liturgy is not due in part to any sort of "inflexible conservatism" or aversion to the idea of change in the Church. Rather, it reflects the degree to which Orthodox appreciate the liturgy for its incredible beauty, its fullness, and the transcendence it allows each worshipper to have when he or she contemplates the mysteries of God's loving kindness, mercy, grace, and majesty.

Despite my discomfort at seeing several mainline Protestant churches currently adapting gender-neutral pronouns to refer to God in their services, or the fact that many evangelical Christian congregations do not even baptize in the name of the Trinity, my love for the Orthodox liturgy is a positive thing that stands alone. I do not constantly compare it to the Mass or to Protestant services each time I stand in St. Nicholas Cathedral on Sunday mornings. Yet the degree to which the Liturgy has inspired the Orthodox faithful over the years is really incredible and worth noting. Most private prayers and personal devotions written by Orthodox over the centuries come directly from the liturgy, in comparison to the Western (both Catholic and Reformed) traditions, where most saints and important laypersons have composed prayers and hymns entirely of their own meditation, with little to no influence from their respective liturgies. Having grown up with many of these vernacular prayers and hymns, I continue to love most of them, but the reality that for centuries the Orthodox faithful have taken their deepest spiritual inspiration from the Liturgy speaks volumes about its unique and compelling draw.

The Orthodox sense of devotion to preserving the Liturgy and Church teachings is perhaps best expressed by the Eastern Patriarchs who told a group of Anglicans in 1718 that

"We adhere to the Faith He delivered to us, and keep it as a Royal Treasure, and a monument of great price, neither adding anything, nor taking anything from it."

St. John of Damascus wrote similarly,

"We keep the Tradition just as we received it."

Ryan Hunter being received into the Orthodox Church

Ryan Hunter being received into the Orthodox Church

This sense of liturgical continuity contrasts markedly with every other Christian tradition, even Roman Catholicism, which has changed the Mass less than most Protestant and evangelical churches have altered their services in recent years. Yet the Vatican II Council dramatically shortened the Ordinary rite of the Catholic Mass, at least partly in an attempt to make it more "doable" for increasingly busy people unwilling to devote more than an hour of their Sunday to sit in church. It is saddening that so few Catholics have ever been able to experience the Latin chants of the Tridentine Mass. Even with Pope Benedict XVI's declaration that the present Extraordinary Form could be sung if people so desired, few actually endeavor to ask their priest to celebrate the Eucharist this way and some priests have been reluctant or unwilling to do so.

To me, the manner in which people worship and the degree to which--or if--it inspires them is indicative of not only their own spiritual health and happiness but the condition and state of their faith in general. I believe in the old principle of lex credendi, lex orandi. Anyone who has felt God's presence in their own personal devotions or in a church service knows how powerfully inspiring it is. Paradoxically, when worship is emotionally stilted or mechanical, when it does not involve all your senses or emotions, when you leave the service without feeling awakened, enlightened, or transformed, you feel disappointed, frustrated, and unfulfilled.

Whether Orthodox or Catholic, Anglican or Low Church Protestant, if you have simply been "going through the motions" on Sunday without really getting much fulfillment out of it (I did this for years) I would humbly challenge you first to concentrate and allow yourself to be more open to contemplation. Try asking yourself:

"If my lips and mouth are praying, is my heart? Is my soul uniting to God?"

Of course there are times when inspiration just doesn't come.

But if you find it impossible or very difficult to concentrate on heartfelt prayer or contemplation of God during your time in church, and if this continues week after week, ask yourself: could it be that the Mass or the service just does not inspire me to the extent that I crave? If your service does not give you a sense of spiritual fulfillment and communion with God, then you might consider thinking on the overall teachings of your denomination.

Ask yourself:

I am by no means advocating that anyone should abandon their specific denomination just because they like the services of another church more than the services in and around which they were raised. To do that would be to trivialize the whole process of deciding to leave or enter a church, which is a profoundly contemplative, gradual, and serious matter. It is dangerous for someone to embrace a whole new faith suddenly or based only on how a service moves them; it is unlikely that the foundation of this new faith has embedded itself deep within them. Regardless of what denomination you come from, if you want to acquire a meaningful understanding of any of the Christian faith traditions, you should endeavor to study the Bible and connect with the intellectual and philosophical doctrines and teachings of your specific Church. "Going through the motions" is never enough to live any kind of fulfilling spiritual life, and anyone who does just that, week after week, will tell you that it leaves them with only a void.

If you are one of potentially millions of American Christians spiritually unsatisfied--profoundly unsatisfied--with what you are hearing, singing, and saying in church on Sundays, I would say to you that you should not feel obligated to continue participating in such a spiritually stagnant environment. One of the most beautiful things about the US is our long tradition of religious freedom. Every world religion and every denomination has a presence here. If you are bored or unsatisfied with your church, whether it's Catholic, Episcopal, Methodist, Presbyterian, Baptist or "non-denominational" evangelical, I urge you to consider the numerous other options that you have! Since God gave us all free will, He surely does not want any of His children to persist in trying to worship Him in a church where they just don't feel the spiritual connection or awareness of God that they crave. So, if you want a new kind of experience, look around you. Visit an Orthodox church.

Come to the liturgy. I promise you, you will be moved--in ways I cannot put into words.

Part II: First experience of Orthodoxy: the Liturgy--Transcendent, Enveloping Beauty

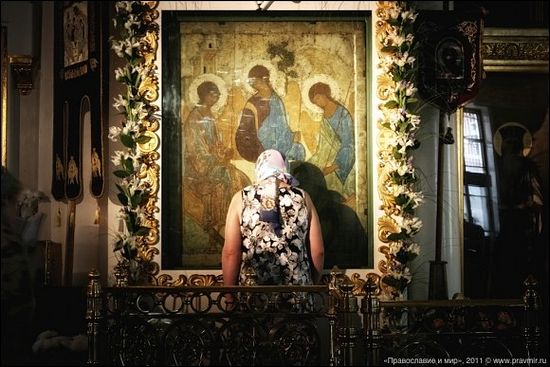

Photo: S.Vlasov / Expo.Pravoslavie.Ru

Photo: S.Vlasov / Expo.Pravoslavie.Ru

My first experience of Orthodoxy was, fittingly, also my first experience witnessing the Divine Liturgy, on the evening of Holy Thursday, April 1, 2010, at Holy Wisdom (St. Sophia) Greek Orthodox Cathedral a few blocks down Massachusetts Avenue from my university. My surroundings initially overwhelmed me--physically, emotionally, and spiritually.

I was no novice to beautiful religious buildings: I had been inside Notre Dame de Paris, la Basilica San Pietro in the Vatican, and more recently, in DC, the Episcopal National Cathedral and the Catholic Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception. An avid student of art history, I had "Googled" images of St. Paul's in London, Westminster Abbey, Jerusalem's Dome of the Rock and the Suleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul. I had seen many beautiful Gothic and Neo-Byzantine style churches, and worshipped in many other Catholic, Anglican, and some Protestant churches. I had also been in beautiful synagogues, mosques, and a Sikh temple.

Having seen these beautiful places, it is still difficult to put into words the extent to which experiencing the Holy Thursday Liturgy of St. Basil affected me over a year ago when I worshipped in Holy Wisdom Cathedral. I went with an ex-girlfriend, one of my closest friends, a Polish Roman Catholic: she never went back, but she saw how much the experience moved me. The whole liturgy--some three hours long--awakened in me an entirely new spiritual plane that nothing else had inspired in me before.

St. Sophia's (referring to the sofia, or wisdom, of God, not a particular saint named Sophia) is a beautiful templon (the Greek word for church is identical to the ancient word for temple) constructed to look like a miniature model of the Hagia Sophia, the Church of the Holy Wisdom in Constantinople. For those unfamiliar with Byzantine history, this larger "Holy Wisdom" was the incredible sixth-century mother church of the Orthodox world and for centuries the world's largest cathedral, famous for its crowning dome that endured many earthquakes. It was the liturgy in this church that inspired the conversion of the Rus. After the Ottoman Turks captured the city in 1453, it was preserved as a mosque, and today is one of Istanbul's most frequently visited tourist attractions. Unfortunately, it has not been reopened as a place of worship: it is a museum.

Hagia Sophia, Istanbul

Hagia Sophia, Istanbul

The smaller Hagia Sophia I visited that April day is similarly very beautiful: with its great dome and high-set windows, it is something altogether out of place in the shadow of the Neo-Gothic Episcopal National Cathedral two blocks away. Yet as with all churches, the true beauty of this temple lies within. To give readers unfamiliar with Orthodox church architecture a sense of how different the Byzantine style is from anything Western, I wish to give the following description:

Entering the cathedral's unfinished narthex (it's still white, as yet unpainted with the golden frescoes and saints' images that dazzle the interior), one immediately notices icon stands in the corner: to your right is Christ, to the left His Mother, the Theotokos (Orthodox give her this title, meaning "bearer of God", dating to the Third Ecumenical Council, since she chose to bear Christ, the New Adam, the Father's Incarnate Son.) Every Orthodox church has a small open shop in the narthex/vestibule area where laypersons, often including the presvytera (Russian: matushka), the priest's wife, sell candles, which the worshippers can light in front of the icons before entering the church. Some people bring their candles unlit into the church proper, and when venerating another icon will place the candle in front of a saint's image.

Upon entering the church interior, your eyes will be dazzled by the vivid colors everywhere: rich gray and dark green marble columns support the soaring pendentives upon which the cathedral's towering central dome rests. Everywhere above and around you, on the gold-painted ceiling and the less-adorned side walls around the windows, you will see Byzantine-style painted frescoes of saints. The large, high-set windows, with colored glass panes, are actually obstacles to seeing outside. The reason for this is so that the church community, or laos, is not distracted by the outside world during the liturgy and can focus wholly on worship in the cathedral.

Rising above the temple are the four Gospel writers, their inscriptions written in Greek, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, taking their places close to the dome. Above them, rising higher in circles, are exalted angels, the "cherubim and seraphim" of the Magnificat. At the top of the dome gazing down on His temple is the image of Christos Pantokrator--Christ enthroned as ruler of the universe. The Savior's placement at the very top of the Cathedral reflects that the dome symbolizes heaven, and, indeed, just as with the great dome at the original sixth-century Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, the dome here seems to hover above the temple, perched delicately on the sturdy Corinthian columns.

You will notice as your eyes come back down to earth the pews--these are uncommon in most American Orthodox churches, an example of "latinizations" that have crept into certain Orthodox architecture over the years, especially in many American Greek churches. Pews are almost nonexistent in many European churches, where several rows of chairs are often placed along the side aisles for use by the elderly or small children. This is how it is at St. Nicholas.

Looking forward you will see that to the right on a slightly raised platform (this is not the altar) there is an elaborately carved chair. This is the thronos for the bishop (episkopos) when he visits the cathedral and presides over the Liturgy.

Unlike in Western Masses or services, Orthodox priests do not usually sit at all during the service. Like the congregation in most churches, they stand reverently before the altar, which symbolizes the throne of God. The Israelites of the first century worshiped liturgically in the Temple at Jerusalem, where a rotation of prescribed daily prayers were said and psalms chanted, and worship was always conducted with the congregants standing, as Christ implies when he speaks to his disciples in Mark 11:25:

When ye stand, praying...

At St. Sophia's, the priests allow people to sit for parts of the liturgy and use the pews. To the left side of the church you will see several low tables or recessional apses. Here, certain icons will be kept, and confessions heard during orthros (the pre-liturgy morning rite.1)

The most visible object you will see is in the inner center of the church, a large partial wall made of columns that rise about a quarter of the way up between the floor and ceiling of the cathedral. Filling the space between the columns you will notice the painted frescoes of saints: to the immediate right of the golden doors is the chief icon of Christ, to the left, that of the Theotokos. The priest and deacons repeatedly cense these during the liturgy, along with other major icons as they process around the church. This large wall is the iconostasis; as you can tell from the name, it bears the church's most important icons. The size and elaborateness of iconostasia vary depending on the size, wealth, and cultural roots of the church; St. Sophia's is made of the marble that Greeks have used in architecture for centuries, while in most Russian churches fine wood and rich carvings are used. In front of the iconostasis are the choir stalls, small platforms from which the canters sing during the liturgy.

The iconostasis is identical in function to the wall and curtain that separated the Holy of Holies, the inner sanctum, of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem from the main areas of the temple proper. As one progressed further into the temple, one tread on increasingly sacred ground, where, by varying degree, the people, elders, and finally most priests were restricted. While in ancient Jerusalem only the high priest could enter the Holy of Holies where the Tabernacle stood, in the Orthodox liturgy all clergy can pass through the doors (traditionally only priests or, when in attendance, the bishop, use the central Beautiful Gate, which also evokes the practice at the Jerusalem Temple.) The reason for this separation is not to prevent the people from seeing the altar, and depending on the local tradition, the Royal Doors might extend very high, or to eye level, or, in some cases, shoulder level, enabling the laity to see most of what goes on in the altar area even when the doors are closed. Traditionally, Russian iconostasia are of greater height than Greek ones.

This visual barrier encourages people to experience the Liturgy with their "spiritual eyes", their hearts and their very souls. The icon wall and the Beautiful Gate serves to remind Orthodox worshipers that they are in a house of God, a holy temple evoking the memory of the ancient Temple at Jerusalem, which was the glory of Solomon and the heart of Israelite worship of the one God. Church tradition and Holy Scriptures maintain that St Joseph and the Blessed Virgin Mary found Jesus as a young boy teaching in the Temple, and the Theotokos served as one of the virgin weavers of the Holy of Holies curtains after her dedication to the Temple when she was a young girl. The Church commemorates Mary's dedication to the Temple in her feast of the Entrance of the Theotokos into the Temple.

Another misconception about Orthodoxy and Orthodox worship is the tradition of the priest facing east, in the direction of the altar. This does not mean that "he turns his back to the people", but that, actually, the priest faces the same direction as the people, leading them in prayer. This is how the Roman Catholic Church celebrated the Mass until the liturgical reforms enacted in the wake of the Second Vatican Council. Generally the altar and the priest's activities within the sacred area are visible to the congregation throughout most of the service, with the Royal Doors being closed (and the curtain shut) only when the clergy finish preparing the Eucharist.

During the joyous Paschal celebration, for instance, the doors are opened--and left open--with great ceremony and thanksgiving, symbolizing Christ's resurrection and that he is free of Death, over which he triumphed. Hence the triumphant words of the paschal midnight sticheron

"Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down Death by death, and among those in the tombs bestowing light!"

As with all things in Orthodoxy, the most important are inexorably related to the Divine Liturgy--thus after Easter Sunday, the faithful greet each other with cries of

"Christ is Risen!" (Response: "Indeed/Truly He is risen!")

Part III: Icons, Images of the Saints and Reverence for the Virgin Mary

Many Protestants and Roman Catholics are unfamiliar with the use of icons in church services or private devotions. In Orthodoxy they play a major role in both, but this role has often been grossly misunderstood. Because Protestant theology eschews many of the older Church traditions that explain the reasons and importance behind these religious images, most Protestants are unaware of their theological importance, believing them instead to be distractions from worshipping God. The perspective I've heard from most of my Protestant friends is that "having so many 'faces' in a church distracts from worshipping God." Others tell me that images of the Blessed Virgin, saints, and angels are either idolatrous, or simply "unnecessary."

I would say that one person's standard of what is "necessary" and "unnecessary" for proper worship is as subjective as the next person's, and that is why respect for the Church's revealed teachings on these matters and a willingness to evaluate and consider the role of centuries of Tradition (including the writings of many prominent Church Fathers, both Latin and Greek) is crucial here. To disregard all this wisdom as "unnecessary" or distracting seems to me to be taking a great liberty.

St. Germanus, mentioned earlier, was Patriarch of Constantinople until iconoclast Emperor Leo III "the Isaurian" (r. 717-741) removed him due to the archbishop's continued and vocal support for the veneration of icons. St. Germanus' defense of icon veneration is most clearly expressed in a letter he wrote to John of Synades, in which the Patriarch states that

It is not to deviate from the perfect worship of God that we allow the production of icons ... For we make no icon or representation of the invisible deity ... But since the only Son Himself, Who is in the bosom of the Father, deigned to become man, according to the good will of the Father and the Holy Spirit, since He became a participant in blood and flesh, like us, as the great apostle says, "Having become similar to us in everything except sin" (Heb 4:15) we draw the image of His human aspect according to the flesh, and not according to His incomprehensible and invisible divinity, for we feel the need to represent what is our faith, to show that He is not united to our nature only in appearance, as a shadow ... but that He has become man in reality and truth.

As St. Germanus writes, our icons never depict God the Father, since He is invisible, as Scripture tells us in many places, most specifically in John 1:18 that No man hath seen God [the Father] at any time.

Any Orthodox or Catholic theologian will tell you that veneration of saints' relics or icons (known as doulia in Greek) differs significantly from latreia, which is the form of worship due to God alone. In our veneration, it is not the images or relics themselves we honor, but the grace of God in them. Doulia of icons and relics retains widespread practice in certain Catholic communities, particularly in South America and Southeast Asia, yet among American Catholics the practice is rare, mainly confined to older faithful, especially those who prefer to use the current Extraordinary form of the Mass, widely known as the Tridentine rite. Neither Catholics nor the Orthodox worship icons, nor do they worship the saints whose assistance they sometimes seek or whose exemplary qualities they seek to follow. This is of course a point of great distinction between Protestants and the older two Christian branches.

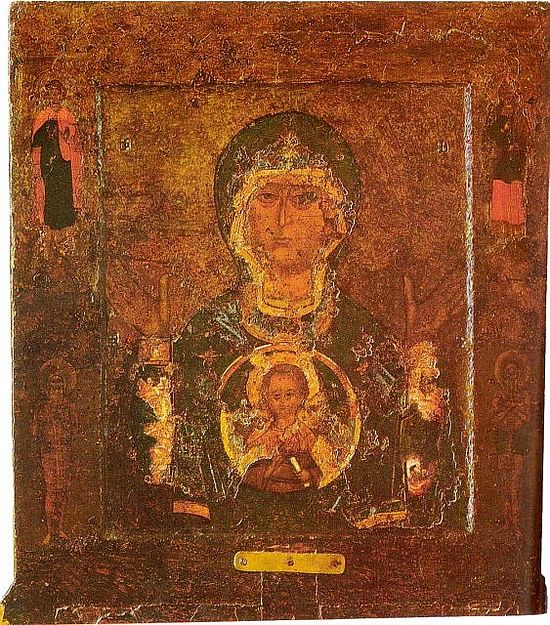

Many of the most famous icons are centuries old and have been attributed to saving certain countries or peoples from disaster, such as Our Lady of the Sign in Russia, which the Russian people to this day venerate for the role attributed to it in saving the city of Novgorod from invasion. Another famous, beautiful icon is known to the Orthodox as the Virgin Theotokos (Mary) of the Passion (familiar to Roman Catholics as Our Lady of Perpetual Help, it is given particular veneration among Filipinos.) The Passion icon is one of many healing icons, as many laity and clergy have reported being healed of their afflictions while praying in front of it. This might seem superstitious to some Protestants disinclined to look favorably on such veneration in the first place, but the records and claims of people claiming miraculous healings exist.

Our Lady of the Sign ("Знамение")

Our Lady of the Sign ("Знамение")

Regarding the Virgin Mary, the Orthodox give her several titles corresponding to her role as Jesus' mother. Because she is Christ's mother, she is therefore mother of the Son of God who was Himself One of the Holy Trinity "before all ages". This is why we call her Mother of God, for she is the mother of the eternal Word, the Logos described in the opening of St John's Gospel. The Church's reasons for honoring Mary are quite simple, and they are Biblical. In Luke 1:43 Elizabeth calls Mary the mother of my Lord. Fr. Alexander Schmemann (1921-1983), Orthodox theologian and former Dean of St. Vladimir's Seminary, observed that Mary is "our link to Christ, and in Him, to God" the Father. She is

The very expression, the very depth of man's "yes" to God in Christ ... the human person that has become totally transparent to the Holy Spirit. If Christ is the "icon" of the Father, Mary is the "icon" of the new creation, the new Eve responding to the new Adam, fulfilling the mystery of love ... Mary is the image and the personification of the world.

Thus, Mary is the natural archetype for mankind, a perfect example for her fellow human beings to imitate. Through her willingness to bear the Savior of mankind, full cooperation with the will of God became something attainable and personal for mankind. Because "she is the one who gave Him His human nature, His flesh and blood, she is the one through whom Christ can always call Himself "The Son of Man.""

Because of Mary's willing cooperation with God

Salvation is no longer the operation of rescuing an ontologically inferior and passive being; it is revealed as truly a synergeia, cooperation between God and man. In Mary, obedience and humility are shown as rooted not in any "deficiency" of nature, but as the very expression of man's royal freedom, of his capacity freely to encounter Truth itself. In the faith and the experience of the Church, Mary truly is the very icon of "anthropological maximalism", its eternal epiphany ... In Mary, the very notions of "dependence" and "freedom" cease to be opposed to one another as mutually exclusive. We are inclined to think that where there is dependence there can be no freedom, where there is freedom there can be no dependence. She, however, accepts, she obeys, she humbles herself before the living Truth itself, a Presence, a Call so overwhelmingly evident.

Because of Mary's "yes" to God's invitation to bear Christ the Savior, she signaled the coming redemption of humankind through her Son. No longer was man cut off from God, for God would enter the world through a woman's body. Mary did not have to accept the role to which God called her; her very acceptance radically changed God's relation to humankind, for it is through Mary that God entered the world as a man, and it is due to Mary's humanity that Christ is "fully man" while also being fully God. Due to her special role as the Mother of Christ, it is only logical that

Mary stands in the very center of the Church's vision of the world, of man and life as the ultimate fruit and therefore the highest expression of that humility and obedience, without which there is no entrance into the mystery of man's true communion with God.

Fr. Alexander affirms her role as mediator and channel between man and God: "Truly she is unique ... and yet she is one of us, she is like us: her life and her experience are fully human."

This is why the Orthodox feel such comfort in the presence of Mary, why we can approach her with our prayers that she might intercede with her Son to save us. She is the natural maternal figure for all humanity to look to for comfort, and through her Son, the very vessel by which the promise of salvation came to our fallen world.

Many Protestants consider the veneration given Mary by both Roman Catholics and Orthodox as something distracting from the latreia due to God alone. Some attribute widespread Marian devotion to a desire originating from pagan influence to have a female presence in the human experience of God. Orthodox and Catholics would answer that every person, man or woman, has the ability to believe in and come to know God, and since God the Logos, the Word, came into the world as the incarnate Son of Man, it is only natural that we seek to know Him through His mother.

Marian devotion in Orthodoxy is entirely Christocentric, revolving around and relating entirely to her role as Jesus' mother. Because Mary is the Father's chosen instrument of bringing His Son into the world, as she states in the Magnificat when she exclaims, "He has regarded the low estate of His handmaiden, from henceforth all generations shall call me Blessed", we believe it is improper not to honor her. Some Catholics and Orthodox condemn as oversimplification and reductionist the tendencies among Protestant theologians and ministers to omit almost any mention of her. Aside from the reference to her in the Creed, she is overwhelmingly "toned down" by most Protestants (excluding High Church Anglicans) who are uncomfortable with her importance in earlier centuries of Christian theological development, and are skeptical of the attention that Christians of the earlier Church traditions pay her.

As with Roman Catholics, Orthodox refer to Mary as the Blessed Virgin, the Mother of God, and often ascribe to her the honorific "Queen" or "Lady", depending on the translation, as she sits beside God the Father and her Son in heaven. One universal Orthodox title for Mary that does not usually appear in the West is the Greek term Theotokos, (lit. "Bearer of God".) Another Greek honorific is Panagia, the "All-Holy" one whom the Father chose to carry His Son into the world, who "without corruption gave birth to God the Word", without the pain and physical changes that alter all other women's bodies during and after childbirth. Having been raised in the Roman Catholic Church, I can attest that devotion to Mary in Orthodoxy is as beautiful and just as much part of the liturgy as it is Roman Catholicism, if not more so.

While the Orthodox do not use the "Hail Mary" in the Liturgy per se (a more correct translation of the Greek 'Chaire' is "Rejoice", rather than 'Hail') at the end of Vespers during an All-Night Vigil the choir will sing, in English "Rejoice O Virgin Theotokos" which is of almost identical wording to the Western Hail Mary.

Every Sunday Liturgy following the conclusion of the anaphora, the clergy and people chant the millennia-old Axion Estin (English: "It is truly meet") which is similar in wording to the Magnificat sung by the choir and people at most All-Night Vigils. The Magnificat (from the Latin "I magnify") is one of the most beautiful and compelling parts of our worship. In the majestic chanting of the choir the people and clergy's voices join together to intone the very words that Mary exclaimed at her Annunciation. Throughout all Eastern Orthodox services, there is never instrumental accompaniment, since Orthodox hold the human voice to be the most pleasing sound to the God who created it.

At the Magnificat, many worshipers are visibly moved--as St. Silouan tells us, tears in prayer are an expression of the heart's desire to know God. Its beauty alone was something that drew me to attend the Saturday evening vigils at St. Nicholas. Every Orthodox church I have attended always offers a beautifully unique composition of the Magnificat, but the style at St Nicholas remains the one most touching to me. The celebrating clergyman comes out from the altar, turns to face the icon of the Blessed Virgin on the iconostasis, which he censes as he cries

The Theotokos and the Mother of the Light, let us magnify in song!

and then, as the choir begins the canticle, he processes around the church, censing all the worshipers as well as the icons of the saints. This is a reminder that the Church sings to the Lord in the presence of all the saints and the angels, who are present invisibly among us as Psalm 137 reminds us. The priest censes the people because Christ, truly God and truly man, bridged the "sacred distance" between heaven and earth, uniting the human and the divine natures in His single personage. Several times during each vigil the presiding clergyman, whether priest or bishop, census us as a salutation to the presence of God in each one of us, and so, when we honor Mary, we remember that it is through her, a person as human as any of us, yet who chose to never sin, that God the Word took on human form and lived among us as Jesus the Christ.

Bookmark.

Interesting. Thanks for posting.

I really appreciate the simple things in a small church sometimes.

The reading of Psalms by a lone chanter during hours (before the main service).

I agree with you, but I must say, as a “cradle”, I read this story with tears of joy in my eyes!

This is your best post!

Save Thy people, O Lord,

and bless Thine inheritance.

Grant victory to Thy Church over her enemies,

and protect Thy people by Thy Holy Cross!

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.