"It out and out says virtually all the contracts and shipping were controlled from New York. Do I need to hunt it up for you, or can you find it from what I have told you? It is the link about the flat bottom boats. Look it up."

You responded:

No link of mine discussed "flat bottom boats" or shipping controlled from New York.

This picture from one of your posts doesn't ring a bell?

This is one of those "flat bottomed boats" which you mentioned.

You'll have to find that one yourself, and when you do, I'll explain how you got it all wrong.

Well here's your chance. I believe this is the post to which I was referring.

This is what it said in the link you provided in that post. (See, I do sometimes read what you write and the links you provide.)

The July 4, 1789, tariff was the first substantive legislation passed by the new American government. But in addition to the new duties, it reduced by 10 percent or more the tariff paid for goods arriving in American craft. It also required domestic construction for American ship registry. Navigation acts in the same decade stipulated that foreign-built and foreign-owned vessels were taxed 50 cents per ton when entering U.S. ports, while U.S.-built and -owned ones paid only six cents per ton. Furthermore, the U.S. ones paid annually, while foreign ones paid upon every entry.This effectively blocked off U.S. coastal trade to all but vessels built and owned in the United States. The navigation act of 1817 made it official, providing "that no goods, wares, or merchandise shall be imported under penalty of forfeiture thereof, from one port in the United States to another port in the United States, in a vessel belonging wholly or in part to a subject of any foreign power."

The point of all this was to protect and grow the shipping industry of New England, and it worked. By 1795, the combination of foreign complication and American protection put 92 percent of all imports and 86 percent of all exports in American-flag vessels.American shipowners' annual earnings shot up between 1790 and 1807, from $5.9 million to $42.1 million.

New England shipping took a severe hit during the War of 1812 and the embargo. After the war ended, the British flooded America with manufactured goods to try to drive out the nascent American industries. They chose the port of New York for their dumping ground, in part because the British had been feeding cargoes to Boston all through the war to encourage anti-war sentiment in New England. New York was the more starved, therefore it became the port of choice. And the dumping bankrupted many towns, but it assured New York of its sea-trading supremacy. In the decades to come. New Yorkers made the most of the chance.

Four Northern and Mid-Atlantic ports still had the lion's share of the shipping. But Boston and Baltimore mainly served regional markets (though Boston sucked up a lot of Southern cotton and shipped out a lot of fish). Philadelphia's shipping interest had built up trade with the major seaports on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, especially as Pennsylvania's coal regions opened up in the 1820s. But New York was king. Its merchants had the ready money, it had a superior harbor, it kept freight rates down, and by 1825 some 4,000 coastal trade vessels per year arrived there. In 1828 it was estimated that the clearances from New York to ports on the Delaware Bay alone were 16,508 tons, and to the Chesapeake Bay 51,000 tons.

Early and mid-19th century Atlantic trade was based on "packet lines" -- groups of vessels offering scheduled services. It was a coastal trade at first, but when the Black Ball Line started running between New York and Liverpool in 1817, it became the way to do business across the pond.

The trick was to have a good cargo going each way. The New York packet lines succeeded because they sucked in all the eastbound cotton cargoes from the U.S. The northeast didn't have enough volume of paying freight on its own. So American vessels, usually owned in the Northeast, sailed off to a cotton port, carrying goods for the southern market. There they loaded cotton (or occasionally naval stores or timber) for Europe. They steamed back from Europe loaded with manufactured goods, raw materials like hemp or coal, and occasionally immigrants.

Since this "triangle trade" involved a domestic leg, foreign vessels were excluded from it (under the 1817 law), except a few English ones that could substitute a Canadian port for a Northern U.S. one. And since it was subsidized by the U.S. government, it was going to continue to be the only game in town.

Robert Greenhalgh Albion, in his laudatory history of the Port of New York, openly boasts of this selfish monopoly. "By creating a three-cornered trade in the 'cotton triangle,' New York dragged the commerce between the southern ports and Europe out of its normal course some two hundred miles to collect a heavy toll upon it. This trade might perfectly well have taken the form of direct shuttles between Charleston, Savannah, Mobile, or New Orleans on the one hand and Liverpool or Havre on the other, leaving New York far to one side had it not interfered in this way. To clinch this abnormal arrangement, moreover, New York developed the coastal packet lines without which it would have been extremely difficult to make the east-bound trips of the ocean packets profitable."[2]

Even when the Southern cotton bound for Europe didn't put in at the wharves of Sandy Hook or the East River, unloading and reloading, the combined income from interests, commissions, freight, insurance, and other profits took perhaps 40 cents into New York of every dollar paid for southern cotton.

The record shows that ports with moderate quantities of outbound freight couldn't keep up with the New York competition. Remember, this is a triangle trade. Boston started a packet line in 1833 that, to secure outbound cargo, detoured to Charleston for cotton. But about the only other local commodity it could find to move to Europe was Bostonians. Since most passengers en route to England found little attraction in a layover in South Carolina, the lines failed.[3]

As for the cotton ports themselves, they did not crave enough imports to justify packet lines until 1851, when New Orleans hosted one sailing to Liverpool. Yet New York by the mid-1850s could claim sixteen lines to Liverpool, three to London, three to Havre, two to Antwerp, and one each to Glasgow, Rotterdam, and Marseilles. Subsidized, it must be remembered, by the federal post office patronage boondogle.

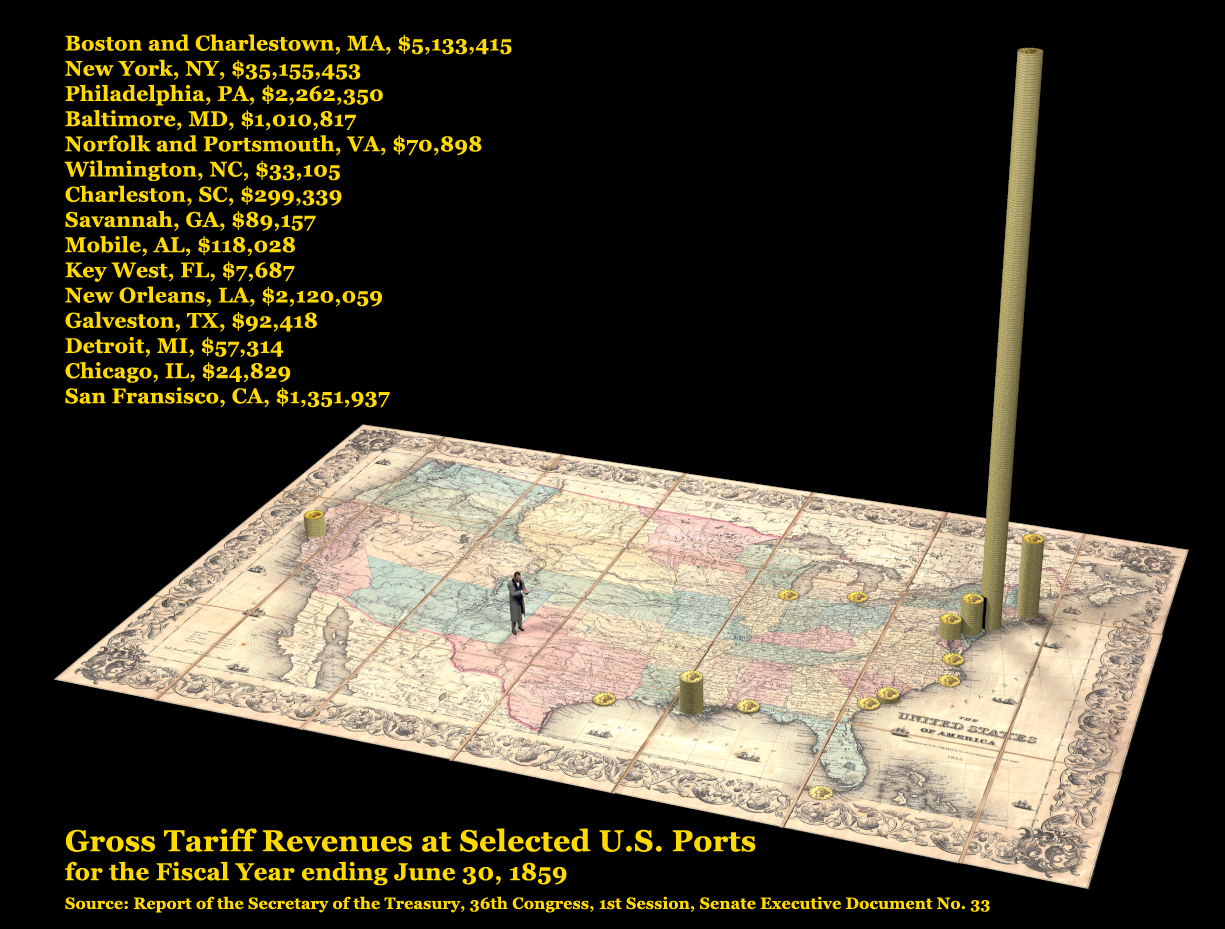

U.S. foreign trade rose in value from $134 million in 1830 to $318 million in 1850. It would triple again in the 1850s. Between two-thirds and three-fourths of those imports entered through the port of New York. Which meant that any trading the South did, had to go through New York. Trade from Charleston and Savannah during this period was stagnant. The total shipping entered from foriegn countries in 1851 in the port of Charleston was 92,000 tons, in the port of New York, 1,448,000. You'd find relatively little tariff money coming in from Charleston. According to a Treasury report, the net revenue of all the ports of South Carolina during 1859 was a mere $234,237; during 1860 it was $309,222.[4]

We noticed.

The war was launched against the South to get back that money. Not to free slaves, not because they gave a D@mn about a stupid fort they had no use for whatsoever, but because of MONEY!