| White | Double |

EVER SINCE THE SUN OF RIGHTEOUSNESS vanished from men’s view, the heaven of holy Church has been illumined through the centuries by the shining light of countless Saints; and even as the brightness of the stars increases as the night advances, so, as we recede from the blessed days of His mortal life, Our Lord sends into the world Saint after Saint whose lives seem to shine with ever-increasing lustre.

EVER SINCE THE SUN OF RIGHTEOUSNESS vanished from men’s view, the heaven of holy Church has been illumined through the centuries by the shining light of countless Saints; and even as the brightness of the stars increases as the night advances, so, as we recede from the blessed days of His mortal life, Our Lord sends into the world Saint after Saint whose lives seem to shine with ever-increasing lustre.

Less than a century ago a tiny village of provincial France was for many years the hub of the religious life of the whole country. Between 1818 and 1859 its name was upon the lips of countless thousands and so great was the affluence of pilgrims that the railway company serving the district had to open a special booking office at Lyons to deal with the traffic between that great city and the little hamlet of Ars. The cause of all this stir was the lowly yet incomparable priest whose story is to be briefly told in these pages.

Like so many other Saints, Jean Baptiste Vianney enjoyed the priceless advantage of being born of truly Christian parents. His father was one of those sturdy farmer-owners who constitute the backbone of a nation. His mother was a native of the small village of Ecully, which, like Dardilly, the Saint’s birthplace, lies within a few miles of the ancient city of Lyons. It would be a huge mistake were we to look upon the Vianneys as rough and ignorant country yokels. No doubt both parents and children were compelled to spend laborious days in field and vineyard, but the consciousness that for several centuries the beloved homestead had belonged to other generations of Vianneys, inspired the family with legitimate pride and they enjoyed the esteem of all who knew them. Kindness to the poor and the needy was an outstanding virtue of the Vianneys. No beggar or tramp was ever driven from their doorstep. Thus it came about that they were privileged, one day, to give hospitality to St Benedict Labre when that patron Saint of tramps passed through Dardilly on one of his pilgrimages to Rome.

He whom the whole world was to know and revere under the touching appellation of “The Curé of Ars,” a title than which none could be dearer to himself, was born on May 8th, 1786, and baptized on the same day. Jean Marie Baptiste was the fourth of a family of six children. His pious mother refused to yield to another what is a mother’s highest duty and sweetest privilege, viz., that of teaching her children to know and love God. Without exception all responded to her loving solicitude, but the keenest of them all was little Jean Baptiste. As a matter of fact, though an elder sister taught him to read and write, even then his mind was particularly responsive to religious knowledge and his memory, always his weakest point, was more retentive of such teaching than of secular learning.

Almost as soon as he was able to walk, the child accompanied his parents into the fields where he tended the sheep and the cows. Great is the charm of that part of rural France. Years later, when he had become the prisoner of the confessional, the holy cure spoke with gentle wistfulness of the verdant valley of the Chante-Merle alive, as its delightful name suggests, with the music of the blackbirds and the murmur of the babbling brook meandering through the meadows, its banks fringed with wild rose bushes and overhung with the branches of ash and elder trees. Here the youthful shepherd would often seek the shelter of some fragrant thicket and, having placed a little statue of Our Lady, which never left him, in a hollow of a big tree, he would kneel on the greensward and pray his little heart out. At other times he would gather other little shepherds and teach them what he had himself learnt at his mother’s knee, thus anticipating the wonderful “catechism” which was to be one of the daily, as it was one of the most fruitful, features of his apostolate at Ars. Even at that early age he was wont to cross himself when the clock struck the hour.

This he did without first looking round to see whether or not he was observed. A neighbour of the Vianneys having caught him in the act laughingly remarked to his father: “That little fellow of yours evidently takes me for the devil: he crosses himself when he sees me!”

All this time dark clouds, big with havoc and disaster, had been gathering over the fair land of France. On November 26th, 1790, the so-called “civil constitution” of the clergy was passed by the National Assembly. All ecclesiastics who refused the oath to this constitution within a week were to be deprived of their benefices. By a decree of the Legislative Assembly, two years later, the non-jurors were to be banished. The following year saw the outbreak of a fierce and bloody persecution. However, the prospect of the guillotine, which was working overtime in most parts of the unhappy country, held no terror for a great many priests who, by the adoption of various disguises and by frequent changes of domicile, somehow contrived to minister to the religious needs of the faithful remnant. Two such priests were M. Balley and M. Groboz. Both worked at Ecully, the one as a baker, the other as a cook, and both were destined to help Jean Baptiste towards the fulfilment of his dearest wish, that of becoming a priest.

Jean Baptiste made his first Communion at Ecully, his mother’s home. The all-important event took place in the early hours of a summer’s day, in a room carefully shuttered for fear of prying eyes. In order to disarm still further any suspicion that might have existed, haycarts had been drawn up beneath the windows and were unloaded with a great show of activity, whilst the solemn ceremony was in progress. The boy was thirteen years old. Even in his old age tears streamed down his cheeks whenever he spoke of that unforgettable day and all his life he treasured the plain rosary beads his mother gave him on the occasion.

Bonaparte’s rise to power gradually brought freedom to the Church. Priests returned from exile or cast away their disguises and, as always, the blood of so many martyrs proved the seed of a new generation of fervent Christians. For a short time Jean Baptiste had frequented a very homely village school, but now that he was growing up the labours of the fields claimed his days. It was during those long hours of toil that the conviction grew in his mind that he must be a priest: “If I were a priest I could win many souls for God,” he said to himself and to his fond mother. In her he found a ready ally, but the rugged father was not to be won over so easily—the lad could ill be spared. Two years had to go by before the head of the family fell in with his son’s aspirations. The new archbishop of Lyons, no less a person than Bonaparte’s uncle, realised only too well that his first care must be the training of recruits for the priesthood. Parish priests were instructed to look out for suitable candidates. M. Balley, now parish priest of Ecully, opened a small school for such boys in his presbytery. Here was young Vianney’s chance. He could go to M. Balley for lessons whilst receiving board and lodging at the house of his aunt. Even Matthieu Vianney saw the advantages of such a scheme. So to Ecully the lad went.

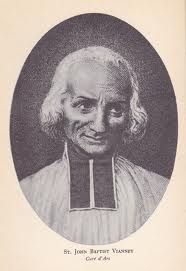

The future Cure’ of Ars was twenty years old when he entered on the studies that were to lead him to the foot of the Altar. Alas ! the first steps in his scholastic career proved arduous in the extreme. Not a few writers and preachers have said, in their haste, that Jean Baptiste Vianney was dull, not to say stupid. Nothing could be further from the truth. A look at the Saint’s authentic picture still suffice to refute these assertions. Every feature of his magnificent head betokens the fine intellect glowing within. His judgment was never at fault, but his memory had lain fallow for so long that it seemed unable to hold what the hapless student strove so manfully to entrust to its keeping. He himself said that “he could not lodge a thing in his bad head.” As he pored, all in vain it seemed to him, over his Latin grammar, pictures rose before his imagination—it was always a vivid one—of the cosy fireside at Dardilly, of his gentle mother, of his beloved brothers and sisters, and the flowery meadows of the valley of Chante-Merle, so that, in an hour of despair, the poor youth almost decided to go home. Happily M. Balley sensed the peril. He bade his pupil go on foot to the shrine of St Francis Regis, at La Louvesc. The pilgrimage proved a turning point. Henceforth his progress was at least sufficient to save him from that awful feeling of discouragement which had so very nearly caused him to give up his studies.

At this very moment an even more formidable crisis arose. Napoleon was astride of Europe, but his brilliant success was paid for with torrents of French blood. More and yet more drafts had to be levied to fill the gaps made in his regiments by their very victories. In 1806 the class to which young Vianney belonged was summoned to the colours before its time. Two years went by, but in the autumn of 1809 Jean Baptiste was summoned to join up, though as a Seminarist he was in reality exempt from conscription. It would seem that the Saint’s name was not on the official list of Church students supplied by the diocesan authorities. Someone had blundered. The recruiting officer would listen neither to expostulation nor to entreaty. Young Vianney was destined for the armies in Spain. His parents tried to find a substitute. For the sum of 3,000 francs and a gratuity, a certain young man agreed to go in his stead but he withdrew at the last moment. On October 26th Jean Baptiste entered the barracks at Lyons only to fall ill. From Lyons they sent him to a hospital at Roanne where the Nuns in charge nursed him back to a semblance of health. When, on January 6th, 1810, infantryman Vianney left the hospital, he found that his draft had set out long ago. There was nothing for it but to try and catch up with it. His only equipment was a heavy bag. An icy wind chilled him to the bone, and a violent fever shook his emaciated frame. Soon he could go no further. Entering a coppice which provided some shelter from the wintry blast he sat down on his bag and began to say his rosary: “Never, perhaps, have I said it with such trust,” he used to say later on. Suddenly a stranger stood before him: “What are you doing here?” he asked. Poor Vianney explained his sorry plight. Thereupon the stranger shouldered the recruit’s bag, at the same time bidding him follow him. By devious paths, through thickets and bushes, the two made their way to the hut of a sabot-maker. Here Vianney lay low for a few days whilst recovering from his fever. As he tossed on his sick bed it suddenly flashed across his mind that, through no fault of his, he was a deserter. He deemed it best to present himself to the mayor of the commune of Les Noes, one Paul Fayot, who was at that very moment sheltering two other deserters. The worthy mayor told the recruit not to worry: it was too late to join his draft; he was now considered a deserter so that his only care must be not to be discovered by the gendarmes. The mayor himself could not keep him, so he handed him over to the care of his cousin, Claudine Fayot, a widow with four children.

Henceforth Vianney assumed the name of Jerome Vincent. Under that name he even opened a school for the village children. For a time, for the sake of greater security, he lived and slept in the byre attached to the farmhouse. During the winter months the village was almost inaccessible, but as soon as the snows melted the danger from visiting gendarmes was constant. One hot summer’s day he nearly died of asphyxiation as he lay hid in a stack of fermenting hay into which one of the gendarmes drove his sword thereby wounding the young man who, as he afterwards confessed, endured such agony that he could not have held out for many more moments. The conduct of all concerned in this affair may seem strange to us, but in those days conscription was not the cast-iron law it subsequently became. Exemptions were numerous and desertion habitual, so much so that in certain parts of France desertion was the rule, obedience to the law the exception and the woods were more densely populated than some of the villages (Cf. Trochu, Life of the Curé d’Ars, page 57). In any case young Vianney was not subject to the law. His being called to the colours was a mistake. Evidently our Saint did not carry in his pack the proverbial marshal’s baton, but even in those early days a supernatural radiance seemed to form a halo round his noble brow. In 1810 an imperial decree granted an amnesty to all deserters of the years 1806 to 1810.

Jean Baptiste was covered by this decree, so that he was free to return home and to resume his studies. Alas ! his beloved mother died shortly after this happy reunion. He was now twenty-four years old and time pressed. Soon the young man returned to the Presbytery of Ecully: On May 28th, 1811, he received the Tonsure. M. Balley deeming it essential that his pupil should go through a regular course of studies, sent him to the Petit Seminaire of Verrieres. Here young Vianney suffered and toiled much but never shone as a philosopher. In October, 1813, he entered the Grand Seminaire of Lyons. His inadequate acquaintance with Latin made it impossible for him either to grasp what the lecturers said or to reply to questions put to him in that learned tongue. At the end of his first term he was asked to leave. His grief and disappointment were indescribable. For a while he toyed with the idea of joining one of the many congregations of Brothers. Once again M. Balley came to the rescue and studies were privately resumed at Ecully. But the student failed at the examination preceding ordination. A private examination at the presbytery proved more satisfactory and was deemed sufficient—his moral qualities being rightly judged to outweigh by far any deficiencies in his academic equipment.

On August 13th, 1815, Jean Baptiste Vianney was raised to the priesthood—to that ineffable dignity of which he spoke so frequently and with so much feeling: “Oh! how great is the priest!” he used to say. “The priest will only be understood in Heaven. Were he understood on earth people would die, not of fear, but of love.” He was twenty-nine years old when, on the morrow of his ordination, he said his first Mass in the chapel of the Seminary of Grenoble where the ceremony had taken place, for Cardinal Fesch had had to flee from Lyons on the fall of his imperial nephew. Two Austrian chaplains of the armies that had invaded France were saying Mass at the same hour at side altars.

On his return to Ecully the Abbe Vianney’s cup of happiness was full when he learnt that he was to be curate to his saintly friend and teacher. The diocesan authorities had decided that for the time being he who was to spend the greater part of his life in the confessional should not have faculties to hear confessions. However, M. Balley secured them for him within a few months and himself became his first penitent. Though in the opinion of his favourite sister Marguerite, who came over from Dardilly on purpose to hear him, “he did not preach well as yet, people flocked to the church when it was his turn to preach.” Between rector and curate there now sprang up a holy rivalry as to who should outdo the other in fasts and penances. Things came to such a pass that the former reported the latter to the ecclesiastical superiors “for exceeding all bounds.” The accused pleaded the example set him by his rector and the Vicar-General laughingly dismissed the two incorrigibles. On December 17th, 1817, M. Balley died in the arms of his beloved pupil who wept for him as one weeps for a father. And he, who was so detached from all things earthly, until the end of his life clung to a small hand-mirror that had belonged to his teacher and father because, he said, “it has reflected his countenance.” Not long after M. Balley’s death M. Vianney was appointed to Ars—a tiny village sleeping among the ponds and monotonous fields of La Dombes which he was destined to make famous for all time.

Even on a large map Palestine is but a narrow strip of arid, desert like land. Yet all that is really great and worth while happened in that barren hill country. The land was made for ever holy in the blessed hour when the heavens opened above it in order to send down the Light of the world.

La Dombes is an uninteresting district of the department of the Ain. The soil is clayey, ponds of stagnant water render the atmosphere moist and heavy, no large woods give colour and life to a landscape of almost unrelieved drabness. Rain is frequent and the climate is soft and enervating. The village of Ars lies in an undulating plain, a knoll rising from its centre and providing as it were a platform for the village church. A small stream, the Fontblin, meanders through the valley and traverses the village. On the west the horizon is shut in by the hills of the Beaujolais. Even today Ars is in no way remarkable, except for the new church, an hotel or two, some charitable institutions and the shops in which is displayed the usual assortment of rosaries, gaudy pictures, and postcards which seem to be the inevitable and commonplace feature of a place of pilgrimage. The inhabitants themselves, for the most part descendants of the good folk who constituted the flock of the most wonderful parish priest the world has known, are seen going about their rustic avocations just as their forefathers did; but the infinitely attractive personality of the immortal Cure seems even now to haunt the streets of the village and the rough tracks—one cannot call them roads—that divide farm from farm.

In 1815 the village consisted of some forty houses. An exceedingly dilapidated church, with no less wretched presbytery, stood on one side of the shallow valley. The only outstanding building was the family mansion of Les Garets d’Ars, but even that structure had lost its turrets and battlements and the moat that surrounded its walls in bygone days had been filled in long ago.

In clerical circles Ars was looked upon as a kind of Siberia. The district was dull, but its spiritual desolation was even greater than the material. It was in the first days of February, 1818, that the Abbe Vianney received official notification of his appointment—it could hardly be called a promotion—to Ars. “There is not much love in that parish—you will instill some into it,” the Vicar-General told him. On February 9th, M. Vianney set out for the place that was to be, for the next forty-one years, the theatre of his astonishing and indeed unprecedented activities. He journeyed on foot, the distance between Ecully and Ars being about 38 km. A wooden bedstead, a few clothes and the books left him by M. Balley followed in a cart. A thick, dank mist lay over the fields so that he lost his way repeatedly. When he got his first glimpse of the village he commented on its smallness but with prophetic instinct added: “The parish will be unable to contain the crowds that will flock hither.”

Though religion was at a low ebb it would be wrong to imagine that none was left. The mere reopening of the churches could not undo the untold harm wrought by the Revolution. The softness of the climate reacted on the natives, making them flabby and pleasure-loving. The faith, however, was not dead and there was at least a nucleus of fervent souls, chief among whom was the lady of “the great house,” Mlle. des Garets, who divided her time between prayer and good works. In company with an old retainer, this wonderful old woman daily recited the whole of the Divine Office.

M. Vianney’s first care was to establish contact with his flock. He made a point of visiting every household in the parish. In those first days he still found time to walk in the fields, his breviary in his hand—he was hardly ever without it—and his three-cornered hat under his arm, for he scarcely ever wore it on his head. He would speak to the peasants about the state of the crops, the weather, their families, so as to win their goodwill. Above all he prayed, and to prayer he joined the most awe-inspiring austerities. He made his own instruments of penance, or at least “improved” them by weighting them with bits of metal or iron hooks. His bed was the bare floor, for he gave away almost at once the mattress he had brought from Ecully. Subsequently he used to speak of the terrible penances of those days as his “youthful follies.” Happy they who have none other to be sorry for or ashamed of! He would go without food for several days at a stretch. There was no housekeeper at the presbytery. Until 1827 the staple of his food was potatoes, an occasional boiled egg and a kind of tough, indigestible, flat cake made of flour, salt, and water which the people called matefaims. Subsequent to the foundation of the orphan girls’ school, to which he gave the beautiful name of “Providence,” he used to take his meals there. At one time he tried to live on grass, but he had to confess that such a diet proved impossible. He himself reveals his mind, as regards all this, in the words he addressed to a young priest: “The devil,” he said, “is not much afraid of the discipline and hair-shirts what he really fears is the curtailing of food, drink and sleep.”

The holy Cure was gifted with a noble imagination and a keen sense of the beautiful. He enjoyed the beauty of fields and woods, but he loved even more the beauty of God’s house and the solemnities of the Church. He began by buying a new altar, with his own money, and he himself painted the woodwork with which the walls were faced. The vestments were worn to shreds. He set himself the task of replenishing what he called, in a touching phrase, “the household furniture of the good God.” Thus it came about that the goldsmiths and embroiderers of Lyons had the amazing experience of seeing a country priest, wearing a shabby cassock, rough shoes, and a battered old hat and who seemingly had not a sou in his pocket, ordering the most expensive articles in their shops. Only the best was good enough for his little village church. The pilgrim to Ars cannot fail to share the wonderment of the craftsmen of Lyons as he reverently contemplates the rows of vestments in the glass cases that line the walls of the Saint’s old presbytery.

The most disastrous sequel of the Revolution was the people’s religious ignorance. The holy Cure resolved to do his utmost to remedy so deplorable a state of affairs. However, his sermons and instructions cost him enormous pain: his memory was so unretentive! Whole nights were spent by him in the little sacristy, in the laborious composition, and in the even more toilsome memorizing of his Sunday discourse. Sometimes he worked thus for seven hours on end. The sermon was delivered with immense energy, often in a high pitched voice, so that he was utterly exhausted at its conclusion. A parishioner asked him one day why he spoke so loud when preaching and so low when praying: “Ah!” he replied, “when I preach I speak to people who are apparently deaf or asleep, but in prayer I speak to God who is not deaf.” The children excited his pity even more than their elders. He began by gathering them in the presbytery and then in the church, as early as six o’clock in the morning, for in the country the day’s work begins at dawn. He was a stern disciplinarian and demanded a word for word knowledge of the text of the catechism.

In those days profanation of the Sunday was rampant in rural France. In the morning the country folk worked in the fields; the afternoon and evening were spent at the dance or in the far too numerous taverns. The holy man inveighed against these evils with astonishing vehemence. At that time inns and taverns were definitely looked upon as places of evil resort. “The tavern,” the Saint declared in one of his sermons. “is the devil’s own shop, the market where souls are bartered, where the harmony of families is broken up, where quarrels start and murders are done.” As for the men who own or run a tavern, “the devil does not greatly trouble them; he despises them and spits on them!” So great did his influence eventually become that the time came when every tavern of Ars had to close its doors for lack of patrons. At a subsequent date modest hostels were opened for the accommodation of strangers, and to these the holy Cure did not object.

Even more strenuous, if possible, were his efforts in bringing about a suppression of dancing—an amusement to which the people were passionately addicted but which the Saint knew only too well to be a very hotbed of sin. Here he met with the most obstinate resistance, and his victory was very slow in coming. At times he himself paid the fiddler engaged for a dance as much as, or more than, the fee he would have earned by his playing, on condition that he stayed away. As a counter-attraction he revived Sunday Vespers. In his struggle against dancing, his zeal carried him to surprising lengths. In I895 an old woman told Mgr. Convert, another parish priest of Ars, that from the age of sixteen to twenty-two she did not make her Easter Communion because the Saint refused her absolution. The reason was that once a year when visiting her relatives in a neighbouring village, on the occasion of the fete of the place, she used to dance for a little while on the village green. The woman added that she went to confession on the eve of all the great feasts but the Saint never absolved her. She only received absolution when, after a resistance of six years, she at last made up her mind to forgo this annual fling.

The Saint was determined to suppress dancing as far as his authority and jurisdiction reached. His master stroke in this long-drawn campaign was to persuade the young women to stay away from these entertainments. Instead of the dance they attended some sodality meeting. The Cure’s success led to an explosion of rage on the part of his enemies: such a man was bound to make enemies ! Their fury vented itself in the vilest calumnies and the grossest libels against this angel in the flesh, and no persecution was deemed too petty or too coarse where he was concerned. That he was keenly sensitive—to it all we gather from a remark he let fall towards the end of his life—had he known all he was to suffer at Ars, he said, he would have died on the day of his arrival. Yet such was his humility that he was perfectly sincere when he expected to be suspended by his bishop and even to be thrown into gaol: “But,” he said, “I do not deserve such a grace.” To these external vexations was added the far more searching trial of dryness in prayer, and at times the lowering clouds of despair cast their dark shadow upon the naturally sunny fields of his spirit.

Two years had gone by when news went forth that M. Vianney was to be cure of Salles, in the Beaujolais. Ars was struck with consternation. Mlle. d’Ars, in a letter to a friend, talked of nothing less than strangling the Vicar-General. The mayor headed a deputation which went to Lyons, where it easily secured the cancelling of the appointment to Salles. To make sure of the future the good people obtained that their village should be erected into a regular parish. M. Vianney was appointed parish priest, for until then he had only been a chaplain who could be removed at a moment’s notice.

That same year the Cure initiated extensive work on the fabric of the church. A low tower was built, a chancel was added to the vane, several side-chapels were erected, particularly a Lady chapel at whose altar he said Mass every Saturday for forty years, and many statues and pictures were placed along the walls of the lowly sanctuary. All these features may still be seen, for when the new, somewhat pretentious church was erected Pius X strictly enjoined that the old church, sanctified by the holy Cure, should remain as he left it. Thus the new basilica is only a prolongation of the lowly village church so dear to the Saint, as it is to the happy pilgrim to Ars. M. Vianney was no obscurantist. He wished to have good schools in the village. To start with he opened a free school for girls, which he called “Providence.” It soon became a boarding school as well as a day school. From 1827 he received none but destitute children as boarders. For them he had to find both food and raiment. More than once God intervened miraculously, multiplying a few grains of wheat in the presbytery attic, or the dough in the kneading trough of the bake-house. The Saint loved the “Providence” above all his undertakings because it existed for the good of destitute children. For the space of twenty years he himself daily came to the establishment to receive the pittance which he dignified with the name of dinner.

In a letter dated November 1st, 1823, to the widow Fayot who had mothered him whilst he lay at Les Noes he wrote that he was in a small parish which was very good and served God with all its heart. Two and a half years had wrought this change. Sunday was now indeed the Lord’s day. The whole village attended Vespers. He found it less easy to induce the good folk to frequent the Sacraments. Jansenism, though moribund, was not yet dead. At the end of his life the Saint declared: “I have done all I could to persuade the men to communicate four times a year: if they had but listened to me they would all be saints.”

The holy priest dearly loved the ceremonies of the Church. He personally trained his altar servers. Corpus Christi was the climax of the liturgical year. On that day he went so far as to forsake his confessional for a few hours. He could be seen walking round the village, admiring and praising the decorations. He himself carried the Blessed Sacrament. No one was allowed to be a mere spectator: strangers were not suffered to line the processional route but everybody had to fall in, and walk in the procession. On his last Corpus Christi day—only forty days before his death—the mayor of the village, Comte des Garets, had secured, unknown to him, the services of a band. At the first crash of the brass and the drums the Saint trembled for sheer joy, and when all was over he could not find words with which to express his gratitude.

His tender love for Our Lady moved him to consecrate his parish to the blessed Queen of Heaven. Over the main entrance of the little church he placed a statue of Our Lady which is still in position. On the occasion of the definition by Pius IX of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, he asked his people to illuminate their houses at night and the church bells were rung for hours on end. What with the blaze visible for miles and the noise of the bells, the surrounding villages imagined Ars was on fire and the fire brigades with their primitive engines were soon on the scene. To this day a silver heart hangs near the statue of Our Lady at Fourvieres containing a parchment on which are written the names of all the parishioners of Ars.

It was to be expected that so signal a triumph of religion, as well as the personal holiness of him who was instrumental in bringing it about, would rouse the fury of hell. The Scriptures tell us that Satan at times disguises himself as an angel of light. In our days he is even more cunning: he persuades people, all too successfully, that he does not exist at all. One of the most amazing features of the life of the Cure of Ars is that during a period of about thirty-five years he was frequently molested, in a physical and tangible way, by the evil one.

It should be borne in mind that all men are subject to temptation—for to tempt to sin is the devil’s ordinary occupation, so to speak—and temptation is permitted by God for our good. Infestation is an extraordinary action of the devil, when he seeks to terrify by horrible apparitions or noises. Obsession goes further: it is either external, when the devil acts on the external senses of the body; or internal, when he influences the imagination or the memory. Possession occurs when the devil seizes on and uses the whole organism. But even then mind and will remain out of his reach. Most of the Cure of Ars’ experiences belong to the first category, viz., infestation.

The powers of darkness opened the attack in the winter of 1824. In the stillness of a frosty night terrific blows were struck against the presbytery door and wild shouting could be heard coming, so it seemed, from the little yard in front of the house. For a moment the Cure suspected the presence of burglars so that he asked the village wheelwright, one Andre Verchere, to spend the following night at the presbytery. It proved an exciting night for that worthy. Shortly after midnight there suddenly came a fearful rattling and battering of the front door whilst within the house a noise was heard as if several heavy carts were being driven through the rooms. Andre seized his gun, looked out of the window but saw nothing except the pale light of the moon: “For a whole quarter of an hour the house shook—and so did my legs,” the would-be defender subsequently confessed. The following evening he received another invitation to spend the night at the presbytery but Andre had had enough.

These and similar disturbances were of almost nightly occurrence. They happened even when the Saint was away from home—in the early years when he was still able to lend a hand to his clerical neighbours. Thus on a certain night during a mission at St Trivier, the presbytery shook and a dreadful noise seemed to proceed from M. Vianney’s bedroom. Everybody was alarmed, and rushing to the Saint’s room the priests found him in his bed which invisible hands had dragged into the middle of the room. M. Vianney soon perceived that these displays of satanic humour were fiercest when some great conversion was about to take place, or, as he playfully put it, when he was about to “land a big fish.” One morning the devil set fire to his bed. The Saint had just left his Confessional to vest for Mass when the cry, “Fire! fire!” was raised. He merely handed the key of his room to those who were to put out the flames: “The villainous grappin!” (it was his nickname for the devil) “unable to catch the bird, he sets fire to the cage!” was the only comment he made. To this day the pilgrim may see, hard by the head of the bed, a picture with its glass splintered by the heat of the flames. It must be remembered that at no time was a fire lit in the hearth and there were no matches in the presbytery.

These molestations were both terrifying and ludicrous. The holy man ended by getting inured to them, so much so that he often poked fun at their author who showed himself in a very poor light indeed. With a smile the Saint once remarked: “Oh! the grappin and myself—we are almost chums.” As a sample of Satan’s sense of humour the following is characteristic of one whom somebody called “God’s ape.” The devil would go on for hours producing a noise similar to that made by striking a glass tumbler with the blade of a steel knife; or he would sing, “with a very cracked voice,” the Saint said, or whistle for hours on end; or he would produce a noise as of a horse champing and prancing in the room, so that the wonder was that the worm-eaten floor did not give way; or he would bleat like a sheep, or miaow like a cat, or shout under the Cure’s window: “Vianney! Vianney! potato-eater.” The purpose of these horrible or grotesque performances was to prevent the servant of God from getting that minimum of rest which his poor body required and thus to render him physically unfit to go on with his astonishing work in the confessional by which he snatched so many souls from the clutches of the fiend. But from 1845 these external attacks ceased almost entirely.

The Saint’s constancy amid such trials was rewarded by the extraordinary power God gave him to cast out devils from the possessed. Nevertheless, horrible as may be the condition of one whose body is possessed by the devil, it is as nothing by comparison with the wretched plight of a soul which, by mortal sin, sells itself, as it were, to Satan. The holy priest may be said to have spent the best part of his priestly career in a direct contest with sin through his unparalleled work in the confessional. The Cure’s confessional was the real miracle of Ars, one that was not merely a passing wonder, or the sensation of a few weeks. Great as were his penances, assuredly the greatest of them all was the endless hours spent by him within the narrow confinement of a rugged, comfortless, unventilated confessional. This miracle went on for forty years. The astonishing thing about M. Vianney is that he himself personally became the object of a pilgrimage, people flocking to Ars in hundreds of thousands just to get a glimpse of him, to hear him, to exchange but a few words with him, above all, to go to confession to him.

The afflux of strangers—the pilgrimage as it soon came to be called—began in 1827. From the year 1828 onward the holy Cure was utterly unable to go away, were it but for one day. Unknown to themselves Saints exercise an irresistible attraction, and however anxiously they may seek obscurity, somehow the children of the Church—and others too—have a knack of discovering them. “Oh, how beautiful is the chaste generation with glory! for the memory thereof is immortal, because it is known both with God and with men! when it is present they imitate it, and they desire it when it hath withdrawn itself.” For all that, no man, perhaps a Saint least of all, can hope to be spared criticism. Thus the Cure’s practice and love of poverty were attributed to avarice: some peculiarly sharp-eyed critics thought they could see in him traces of hypocrisy or a secret desire of notoriety. His meekness and humility ended by winning over his very fault-finders. On one occasion, when his professional competence was questioned by some brother priests, the bishop of the diocese sent his Vicar-General to look into the matter and to report to him. The report was more than favourable. Madame des Garets once remarked in the hearing of the bishop—Mgr. Devie—that people thought M. Vianney was not very learned. The answer was remarkable: “He may or he may not be learned, but I do know that he is enlightened by the Holy Ghost.” The same prelate requested the holy Cure to send in written solutions of his most difficult cases of conscience. In ten years he sent in two hundred admirable solutions.

It may be said that the confessional was M. Vianney’s habitual abode. Even in the depth of winter he daily spent from eleven to twelve hours in that penitential box. The peak of the “pilgrimage” was reached in 1845. At that time there were, on an average, some three to four hundred visitors each day. The railway tickets issued at Lyons had to be made available for eight days, for it was well known that a visitor often had to wait all that time before he could hope to speak to the Saint. In the last year of the Cure’s life the number of pilgrims reached the amazing total of 100 to 120 thousand persons. Parties of pilgrims often camped in the open, for there were only five hostelries in the village and these self-styled hotels could only accommodate some 150 guests between them.

No priestly function is apt to become a greater weariness to the flesh and the spirit than a protracted sitting in the confessional. This arduous duty M. Vianney discharged for many hours, day by day, year in, year out, when chilled to the bone by the hard winters of central France or when all but overcome by the stifling heat of the long summer days. Even his hard-working parishioners had their days of rest—for him alone there was no repose, no respite, no holiday. At all seasons his working day consisted of twenty hours out of twenty-four. In summer he spent as much as fifteen and even sixteen hours in the confessional. Yet he loved the beauty of nature. How he would have revelled in the sunshine, the charm of mellow autumn days, the fragrance and colour of blossoming orchards and flowery meadows! But all he had to look forward to, day after day, was the same confinement in the dark, ill-ventilated wooden box which was for him what the cangue was for the martyrs of Cochin-China.

God alone knows the miracles of grace wrought within that rough confessional which stands to this day where he himself placed it in the chapel of St Catherine; or in the tiny sacristy where he usually heard the men. It was there that his prophetic intuitions and illuminations were most in evidence. In dealing with souls he was infinitely kind. His exhortations were brief and to the point. He said little, only a word or two—but coming from him it meant so much: “To Heaven!” was all he said to a certain priest and when his bishop knelt at his feet he merely said: “Be kind to your priests.”

One day he was hearing confessions in the sacristy. All of a sudden he came to the door and told one of the men who acted as ushers to call a lady at the back of the church, telling him how he could identify her. However, the man failed to find her. “Run quickly,” the Saint said “she is now in front of such a house.” The man did as he was told and found the lady who was going away, bitterly disappointed at not having spoken to the Saint. When reproached with excessive leniency, he replied that he could not be hard on people who had undergone so many hardships merely to see him. At times he came out of the confessional and summoned certain persons from among the crowd and those so selected declared that only a divine instinct could have told him of their peculiar and pressing need.

Of his gift of prophecy one instance must suffice—it is of enormous interest to us in England. On May 14th, 1854, Bishop Ullathorne called on the holy man and asked him to pray for England. The bishop of Birmingham relates that the man of God said with an accent of extraordinary conviction: “Monseigneur, I believe that the Church in England will be restored to its splendour.” May this prophecy receive a full and speedy fulfilment—not least through the prayers of him who made it!

No account of the life of the Cure of Ars would be complete without at least a passing mention of his singular devotion to St Philomena, the celebrated Virgin and Martyr of the early Church, whose tomb was found in the Roman catacombs at the beginning of the last century. Between the austere priest and the youthful Martyr there existed a friendship of extraordinary tenderness. Maybe there are across the centuries spiritual affinities between the Saints to which we have not the key. Be this as it may, the holy Cure looked upon St Philomena as his special guardian: his “agent with God,” as he used to say. He erected a chapel and a shrine in her honour when he undertook the restoration of the village church. This shrine may be seen to this day. In May, 1843, he fell so ill that the end seemed at hand. He promised to have a hundred Masses said at the Saint’s shrine. On May 12th, whilst the first of them was being said, he entered into a trance or ecstasy during which he was heard to murmur repeatedly: “Philomena!” Presently he exclaimed: “I am cured!” He attributed his recovery to St. Philomena. There can be no doubt that he used the Saint as a kind of screen for his own humility, for he attributed to the Martyr the miracles he himself performed. In his wonderful single-mindedness he imagined that the world would be as simple as himself and would not see through this pretty device of his modesty.

One temptation pursued the man of God almost all through his career at Ars, viz., a longing for solitude. There can be but little that, in sheer despair of hurting him in any other way, the devil played on this craving with his wonted astuteness. The Saint’s very humility egged him on towards a step which is almost incomprehensible. In all sincerity M. Vianney deemed himself utterly unfit for his office. The year before his death he said to a missionary: “You do not know what it is to pass from the cure of souls to the tribunal of God.” In 1851 he begged his bishop’s leave to resign. The letter was signed: “J.M.B. Vianney, the poor parish priest of Ars.” On three separate occasions he actually left the village. The first “flight,” as the attempt was called, occurred in 1840—but he returned almost before he had reached the outskirts of the village. In 1843 he had a severe illness—the result of his “youthful follies.” He seemed doomed—but he retained his sense of humour: “I am putting up a grand fight,” he said. “Against whom, M. le Curé?” “Against four doctors! if a fifth joins them I am lost.” He recovered. Again he “fled.” This time he got as far as Dardilly, but after a few days he realized that God wanted him at Ars. In 1853 he made a last attempt, this time with the intention of entering a Trappist monastery. But those on whose assistance he relied betrayed the secret! he was stopped en route. After some parleying he abruptly turned round, took the road to Ars, went straight into the church, put on his surplice and stole and entered his confessional. He realized at last, as he himself confessed, that there was something intemperate in his craving for solitude. Henceforth he was resolved to live and die as Curé of Ars.

Men of the moral stature of the Cure of Ars need no adventitious title or dignity to enhance their personality nor are they ever in danger of attaching undue value to such things. Towards the end of October, 1852, the bishop of Belley arrived unexpectedly at Ars. When his presence was made known to the Saint he issued from his usual abode—the confessional—and came to greet the prelate, in fact, he even made a little speech. Presently the bishop produced a bundle from under his cape which proved to be a Canon’s mozetta which he forthwith tried to put over the Saint’s shoulders at the same time hailing him as Canon Vianney. The poor Cure struggled desperately to shake off the ornament. Meanwhile the bishop intoned the Veni Creator and a procession was formed to escort the unhappy recipient of the honour to the steps of the Altar. All the time the mozetta was hanging precariously from the shoulders of the new dignitary. Not many days later he sold it for fifty francs and wrote to the bishop, thanking him for his providential gift, for just then he needed that much money to complete the sum required for a Mass foundation.

Not long after Napoleon III bestowed on him the Legion d’honneur. On being informed of it, the Saint asked: “Is there any money attached to it? Money for my poor?” When told that there was not, he requested the Comte des Garets to return the decoration to the emperor! Only by a ruse could he be induced to open the box containing the cross: he was told there might be relics in it; but he firmly refused to allow the cross to be pinned to his breast—in fact he gave it to the priest who had been deputed to invest him with it: “Take it,” he said, “my friend, and may you have as much pleasure in receiving it as I have in giving it to you!”

Forty-one years had gone by since the blessed day on which M. Vianney had come to Ars. They had been years of indescribable activity. The lowly priest had become famous not only throughout France—his name had reached the ends of the earth. Eternity alone will reveal the extent of the achievement of those years, so fruitful and blessed for others, but so laborious and exhausting for himself. The end was now in sight. After 1858 he often said: “We are going; we must die; and that soon!” There can be no doubt that he knew the end was at hand. In July, 1859, a devout lady of St Etienne came to confession to him. When she bade the Saint farewell he said: “We shall meet again within three weeks.” Both died within that time and thus met in a happier world.

The month of July of the year 1859 was extraordinarily hot, pilgrims fainted in great numbers, but the Saint remained in his confessional. Friday, July 29th, was the last day on which he appeared in his church. That morning he had entered his confessional about 1 a.m. but after several fainting fits he was compelled to rest. At 11 he gave his catechism—for the last time. That night he could scarcely crawl up to his room. One of the Christian Brothers helped him into bed but, at his request, left him alone. About an hour after midnight he summoned help: “It is my poor end,” he said; “call my confessor.” The illness progressed rapidly. In the afternoon of August 2nd he received the Last Sacraments: “How good God is,” he said; “when we can no longer go to Him, He comes to us.” Twenty priests with lighted candles escorted the Blessed Sacrament—but the heat was so suffocating that they put them out. Tears were trickling down the Saint’s cheeks: “Oh! it is sad to receive Holy Communion for the last time!” he said. On the evening of August 3rd, his bishop arrived. The Saint recognized him though he was unable to utter a word. Towards midnight the end was obviously at hand. At 2 o’clock in the morning of August 4th, 1859, whilst a fearful thunderstorm burst over Ars, and whilst M. Monnin read these words of the “Commendation of a Soul”: May the holy angels of God come to meet him and conduct him into the heavenly Jerusalem, the Cure of Ars gave up his soul to God.

The funeral of the servant of God was a triumph, though all eyes were filled with tears. More than three hundred priests walked before the coffin. So many were the visitors to Ars that provisions gave out and many pilgrims had to go without food. Miracles soon confirmed the reputation for sanctity the man of God had enjoyed during his lifetime. On January 8th, 1905, Pius X, that other lowly yet incomparably great priest, beatified the Cure of Ars. It was reserved for another Pope who bore the name Pius to set the seal upon the heroic virtues of the most wonderful parish priest the world has ever seen. On the feast of Pentecost, May 31st, 1925, amid unparalleled splendour and in the presence of an immense multitude representative of all mankind—for it was the year of Jubilee—surrounded by thirty-two Cardinals and two hundred Bishops, Pius XI pronounced the solemn sentence which amplifiers carried to the furthermost corners of the great basilica: “We declare Jean Marie Baptiste Vianney to be a Saint and inscribe him in the catalogue of the Saints.”

The words were hailed with loud applause; the Te Deum was sung with enthusiasm, all the bells of Rome rang a joyful peal and at nightfall the greatest church of Christendom was illumined with many thousands of lamps whose flickering light appeared to the beholder as so many symbols of the countless souls now shining in heaven, thanks to the heroic toil and self-sacrifice of the new Saint.